Psychosocial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women with Spinal Cord Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures and Recruitment

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic and Disability Characteristics

2.2.2. Assessment of the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.3. Analysis Plan

2.3.1. Qualitative Analysis: Thematic and Sentiment Analysis

2.3.2. Sentiment Coding Training and Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Themes Identified

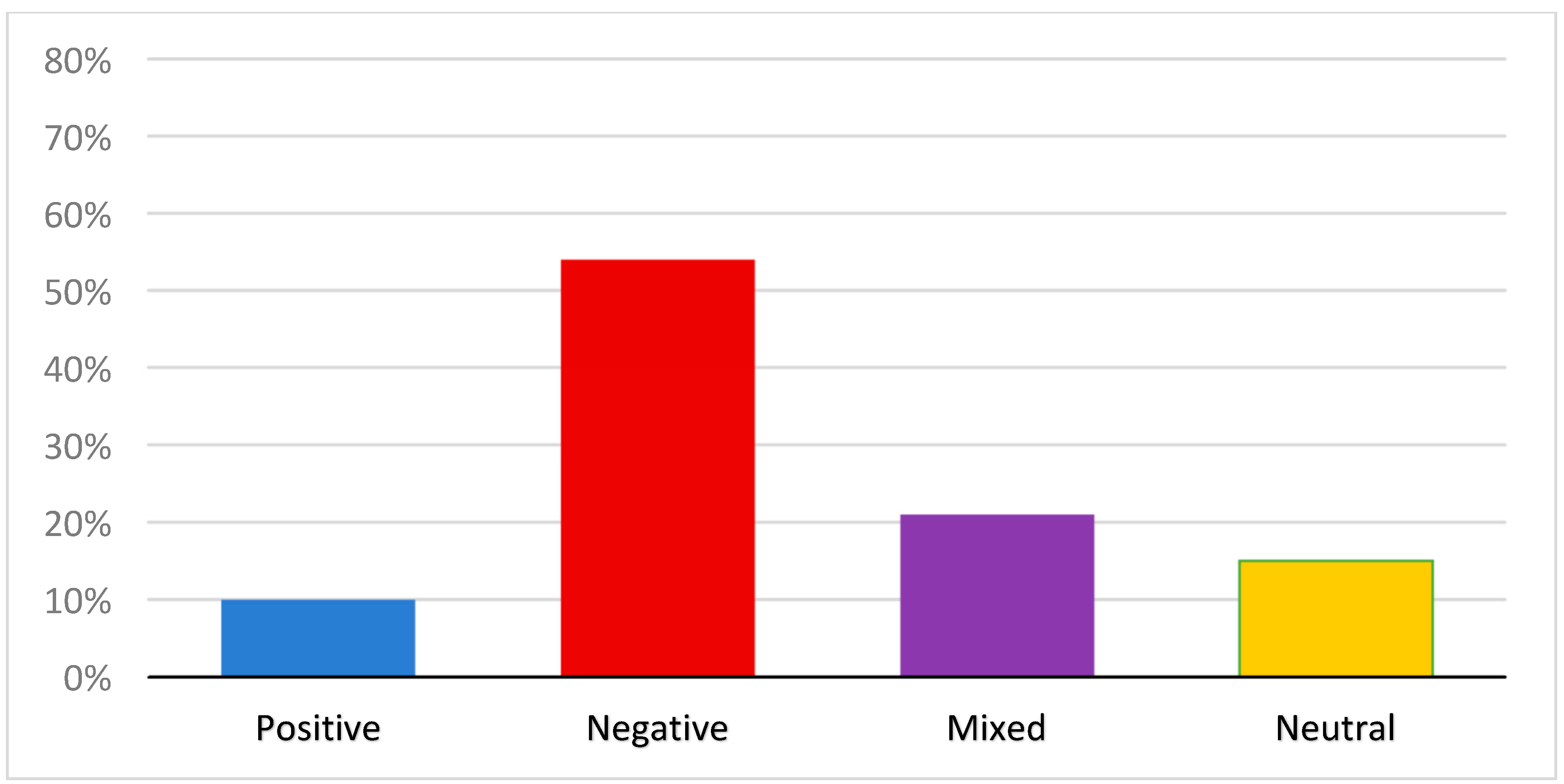

3.3. Sentiment of Overall Impact

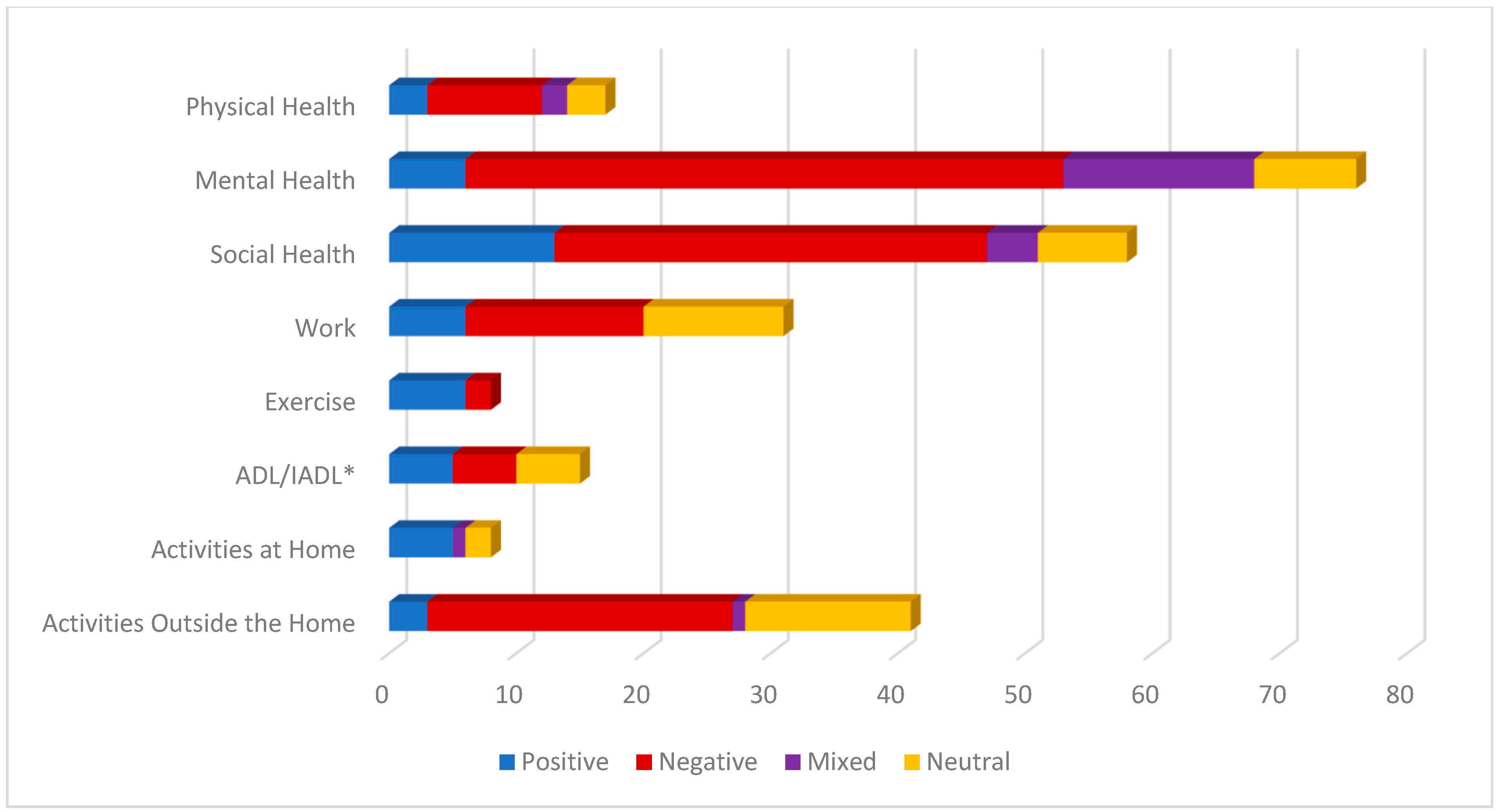

3.4. Frequency and Sentiment of Individual Themes

3.4.1. Physical Health

3.4.2. Mental Health

3.4.3. Social Health

3.4.4. Activities of Daily Living (ADL/IADL)

3.4.5. Exercise

3.4.6. Work

3.4.7. Activities Outside of the Home

3.4.8. Activities at Home

3.5. Relationship of Demographic and Disability Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Women and UNDP Report: Five Lessons from COVID-19 for Centering Gender in Crisis. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2022/06/un-women-and-undp-report-five-lessons-from-covid-19-for-centering-gender-in-crisis#:~:text=Feature-,UN%20Women%20and%20UNDP%20report%3A%20Five%20lessons%20from%20COVID%2D19,for%20centring%20gender%20in%20crisis&text=The%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic%20has,increase%20in%20unpaid%20care%20work (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Andrews, E.E.; Ayers, K.B.; Brown, K.S.; Dunn, D.S.; Pilarski, C.R. No body is expendable: Medical rationing and disability justice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.M.; Ayers, K.B. Raising awareness of disabled lives and health care rationing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, S210–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.M.; Ayers, K.B. Ever-changing but always constant: “Waves” of disability discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council on Disability. 2021 Progress Report: The Impact of COVID-19 on People with Disabilities. Available online: https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_COVID-19_Progress_Report_508.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Pendergrast, C.B.; Monnat, S.M. Perceived impacts of COVID-19 on wellbeing among US working-age adults with ADL difficulty. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, C. Financial hardship experienced by people with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.E.; Sainio, P.; Parikka, S.; Koskinen, S. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychosocial well-being of people with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, A.; Hatton, C.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Aitken, Z.; King, T.; Hastings, R.; Totsika, V.; Llewellyn, G.; Emerson, E. Health and healthcare for people with disabilities in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Women with Disabilities Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/enable/WWD-FactSheet.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- United Nations Population Fund. The Impact of COVID-19 on Women and Girls with Disabilities. A Global Assessment and Case Studies on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, Gender-Based Violence, and Related Rights. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/NEW_UNPRPD_UNFPA_WEI_-_The_Impact_of_COVID-19_on_Women_and_Girls_with_Disabilities.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Supporting Women with Disabilities to Achieve Optimal Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/women-disabilities/index.html#print (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- An Introduction to the Washington Group on Disability Statistics Question Sets. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/primer.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Fact Sheet: Spinal Cord Injury. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/spinal-cord-injury (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury Facts and Figures at a Glance. Available online: https://msktc.org/sites/default/files/SCI-Facts-Figs-2022-Eng-508.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Forber-Pratt, A.J.; Burdick, C.E.; Narasimham, G. Perspectives about COVID-19 vaccination among the paralysis community in the United States. Rehabil. Psychol. 2022, 67, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogenes, B.; Querée, M.; Townson, A.; Willms, R.; Eng, J.J. COVID-19 and Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Presentation, Clinical Course, and Clinical Outcomes: A Rapid Systematic Review. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, M.; Limbu, S.; Sherpa, P.D. Living with spinal cord injury during COVID-19: A qualitative study of impacts of the pandemic in Nepal. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearn, J.H.; Rohn, E.J.; Monden, K.R. Isolated and anxious: A qualitative exploration of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals living with spinal cord injury in the UK. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 45, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczyk, B.; Draganich, C.; Philippus, A.; Goldstein, R.; Erin, A.; Pilarski, C.; Wudlick, R.; Morse, L.R.; Monden, K.R. Resilience and mental health in individuals with spinal cord injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. Spinal Cord 2021, 59, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monden, K.R.; Andrews, E.; Pilarski, C.; Hearn, J.; Wudlick, R.; Morse, L.R. COVID-19 and the spinal cord injury community: Concerns about medical rationing and social isolation. Rehabil. Psychol. 2021, 66, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinicchio, D.; Maroto, M.; Chai, L.; Lukk, M. Findings from an online survey on the mental health effects of COVID-19 on Canadians with disabilities and chronic health conditions. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, K.; Heeb, R.; Walker, K.; Tucker, S.; Hollingsworth, H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Psychosocial Health of Persons with Spinal Cord Injury: Investigation of Experiences and Needed Resources. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2022, 28, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives Alvarado, J.R.; Miranda-Cantellops, N.; Jackson, S.N.; Felix, E.R. Access limitations and level of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in a geographically-limited sample of individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 45, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-Whelen, S.; Hughes, R.B.; Taylor, H.B.; Holmes, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Manohar, S. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with spinal cord injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2023, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoo, H.E.; Loh, H.C.; Ch’ng, A.S.H.; Hoo, F.K.; Looi, I. Positive impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and public health measures on healthcare. Prog. Microbes Mol. Biol. 2021, 4, a0000221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Swilam, M.M.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Du, M.; El-Seedi, H.H.R.; Kai, G.; Masry, S.H.D.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Zou, X.; Halabi, M.F.; et al. Beyond the Pandemic: COVID-19 Pandemic Changed the Face of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.R.; Stephenson, R. Positive and Negative Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Relationship Satisfaction in Male Couples. Am. J. Mens. Health 2021, 15, 15579883211022180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne’eman, A.; Maestas, N. How Has COVID-19 Impacted Disability Employment? Disabil. Health J. 2023, 16, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.R.; L’Hotta, A.J.; Kennedy, C.R.; James, A.S.; Fox, I.K. Living with Cervical Spinal Cord Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2022, 4, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reber, L.; Jodi, M.K.; DeShong, G.; Meade, M. Fear, Isolation, and Invisibility During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study of Adults with Physical Disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, W.N. Qualitative Data, Analysis, and Design. In Introduction to Educational Research: A Critical Thinking Approach, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 342–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Khan, S.U.; Kalra, A. COVID-19 pandemic: A sentiment analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3782–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P.; Kumar, A.; Srivastava, P.; Prajapati, R. Sentiment Analysis and Predictions of COVID 19 Tweets using Natural Language Processing. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Atteveldt, W.; van der Velden, M.A.C.G.; Boukes, M. The Validity of Sentiment Analysis: Comparing Manual Annotation, Crowd-Coding, Dictionary Approaches, and Machine Learning Algorithms. Commun. Methods Meas. 2021, 15, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, M.; Pettinicchio, D.; Chai, L.; Holmes, A. “A Rollercoaster of Emotions”: Social Distancing, Anxiety, and Loneliness Among People with Disabilities and Chronic Health Conditions. In Disability in the Time of Pandemic; Research in Social Science and Disability; Carey, A.C., Green, S.E., Mauldin, L., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023; Volume 13, pp. 49–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, E.J.; Hearn, J.H.; Philippus, A.M.; Monden, K.R. “It’s been a double-edged sword”: An online qualitative exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with spinal cord injury in the US with comparisons to previous UK findings. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, L.; McDonald, R.; Lentin, P.; Bourke-Taylor, H. Facilitators and barriers to social and community participation following spinal cord injury. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2016, 63, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilcher, S.J.T.; Catharine Craven, B.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L.; Cimino, S.R.; Hitzig, S.L. An examination of objective social disconnectedness and perceived social isolation among persons with spinal cord injury/dysfunction: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Whelen, S.; Taylor, H.B.; Feltz, M.; Whelen, M. Loneliness Among People with Spinal Cord Injury: Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the 3-Item Loneliness Scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, L.; Deal, J.A.; Samuel, L.; Reed, N.S.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Swenor, B.K. Access to food and health care during the COVID-19 pandemic by disability status in the United States. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C. Food insecurity of people with disabilities who were Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.B.; Lund, E.M.; Gabrielli, J.; Powers, L.E.; Curry, M.A. Prevalence of interpersonal violence against community-living adults with disabilities: A literature review. Rehabil. Psychol. 2011, 56, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wake, A.D.; Kandula, U.R. The global prevalence and its associated factors toward domestic violence against women and children during COVID-19 pandemic—“The shadow pandemic”: A review of cross-sectional studies. Womens Health 2022, 18, 17455057221095536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevarley, F.M.; Thierry, J.M.; Gill, C.J.; Ryerson, A.B.; Nosek, M.A. Health, preventive health care, and health care access among women with disabilities in the 1994–1995 National Health Interview Survey, Supplement on Disability. Womens Health Issues 2006, 16, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 43.20 ± 13.09 |

| Race | |

| White | 85 (81.0) |

| Black | 9 (8.6) |

| Native American | 1 (1.0) |

| Asian | 2 (1.9) |

| Multiracial | 7 (6.7) |

| Missing | 1 (1.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic | 96 (91.4) |

| Hispanic | 9 (8.6) |

| Level of Education | |

| Less than high school | 2 (1.9) |

| High school grad, GED | 10 (9.5) |

| College, less than 4 years | 29 (27.6) |

| Associate or bachelor’s degree | 40 (38.1) |

| Master’s/doctoral degree | 24 (22.9) |

| Employment Status | |

| Full-time | 17 (16.2) |

| Part-time | 23 (21.9) |

| Unemployed | 65 (61.9) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married | 30 (28.6) |

| Unmarried couple | 18 (17.1) |

| Single, never married | 34 (32.4) |

| Divorced | 18 (17.1) |

| Separated | 1 (1.0) |

| Widowed | 4 (3.8) |

| Household Income | |

| <$15,000 | 19 (18.1) |

| $15,000–$24,000 | 15 (14.3) |

| $25,000–$49,000 | 20 (19.0) |

| $50,000–$74,000 | 16 (15.2) |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 11 (10.5) |

| Over $100,000 | 18 (17.1) |

| Don’t know | 6 (5.7) |

| Community Environment | |

| City or large town | 43 (41.0) |

| Suburb or just outside a city or large town | 29 (27.6) |

| Small town | 25 (23.8) |

| The country or a long way from town | 8 (7.6) |

| Level of Injury | |

| Paraplegia | 56 (53.3) |

| Tetraplegia | 49 (46.7) |

| Time Since Injury | 17.47 ± 13.09 |

| Primary Locomotion | |

| Power wheelchair | 42 (40.0) |

| Manual wheelchair | 57 (54.3) |

| Ambulatory | 6 (5.7) |

| Personal Assistance Needed | |

| No Help Needed | 34 (32.4) |

| Help needed with ADL OR IADL | 28 (26.7) |

| Help needed with both ADL and IADL | 43 (41.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, H.B.; Hughes, R.B.; Gonzalez, D.; Bhattarai, M.; Robinson-Whelen, S. Psychosocial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women with Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146387

Taylor HB, Hughes RB, Gonzalez D, Bhattarai M, Robinson-Whelen S. Psychosocial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women with Spinal Cord Injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(14):6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146387

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Heather B., Rosemary B. Hughes, Diana Gonzalez, Muna Bhattarai, and Susan Robinson-Whelen. 2023. "Psychosocial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women with Spinal Cord Injury" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 14: 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146387

APA StyleTaylor, H. B., Hughes, R. B., Gonzalez, D., Bhattarai, M., & Robinson-Whelen, S. (2023). Psychosocial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women with Spinal Cord Injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146387