Anxiety, Attachment Styles and Life Satisfaction in the Polish LGBTQ+ Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Minority Stress Theory

1.2. Subjective Well-Being Model

1.3. Attachment Styles Concepts

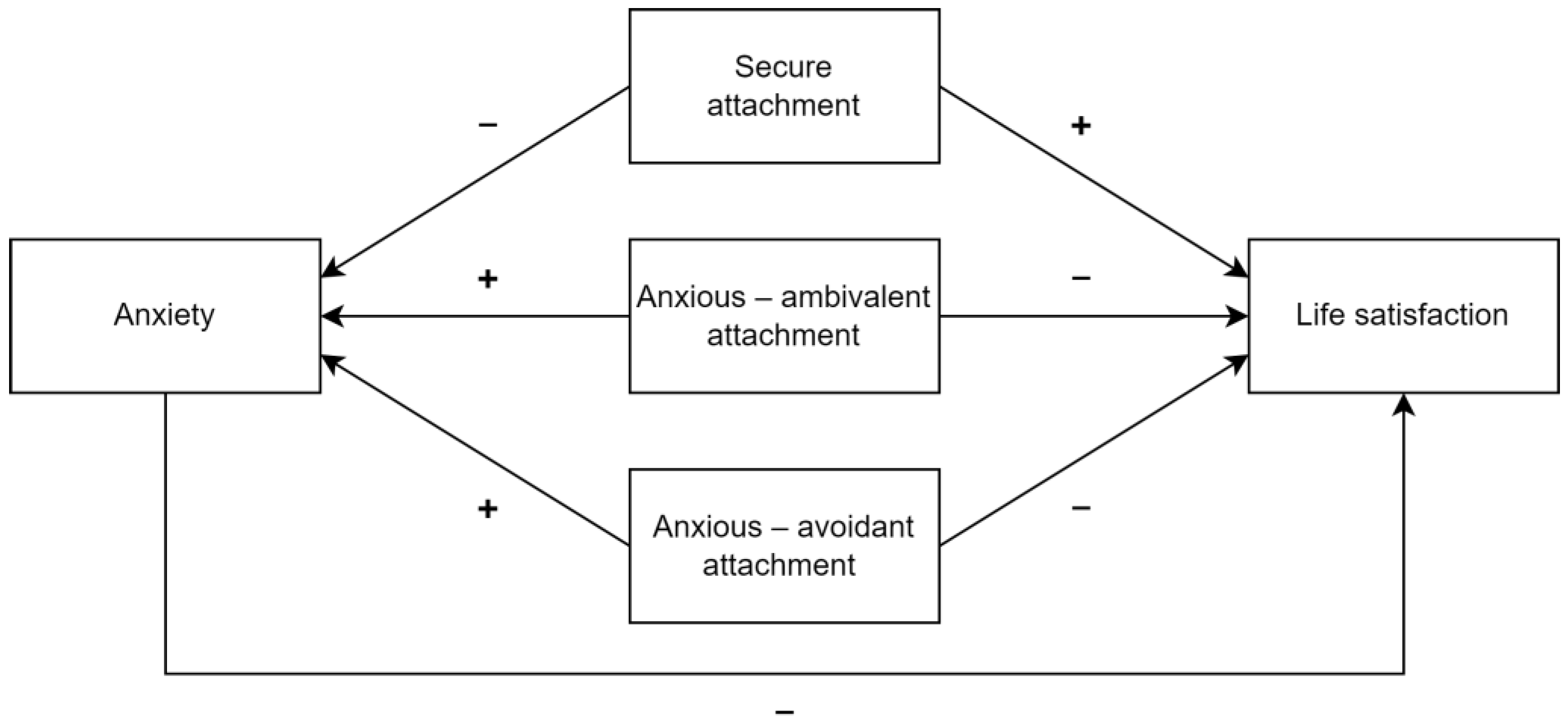

1.4. Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BBC. Polish Election: Andrzej Duda Says LGBT “Ideology” Worse than Communism; BBC News: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Time. Polish President Calls “LGBT Ideology” More Harmful Than Communism; TIME USA, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ILGA Europe. Rainbow Europe 2023; ILGA-Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerymski, R.; Gaworska, A. Does Hormone Treatment Help Polish Transgender Individuals Cope with Stress? J. Sex. Ment. Health 2023, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gerymski, R. Wsparcie i Radzenie Sobie Ze Stresem Jako Moderatory Związku Stresu i Jakości Życia Osób Transpłciowych. Czas. Psychol. 2018, 24, 607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Powdthavee, N.; Wooden, M. Life Satisfaction and Sexual Minorities: Evidence from Australia and the United Kingdom. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 116, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerymski, R. Short Sexual Well-Being Scale–A Cross-Sectional Validation among Transgender and Cisgender People. Health Psychol. Rep. 2021, 9, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnen, C.; Sanderman, R.; Sprangers, M.A. Adult Attachment as Mediator between Recollections of Childhood and Satisfaction with Life. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2009, 16, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, C.Q.; Huebner, E.S. Attachment Relationships and Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction: Some Relationships Matter More to Girls than Boys. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.B.; Nagle, R.J. Parent and Peer Attachment in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradford, E.; Lyddon, W.J. Assessing Adolescent and Adult Attachment: An Update. J. Couns. Dev. 1994, 73, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsar, A.A.H.; Bonab, B.G. Relation between Quality of Attachment and Life Satisfaction in High School Administrators. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sumer, H.C.; Knight, P.A. How Do People with Different Attachment Styles Balance Work and Family? A Personality Perspective on Work–Family Linkage. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.A. Influence of Attachment Styles on Romantic Relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, S.G.; Biss, W.J. Equality Discrepancy between Women in Same-Sex Relationships: The Mediating Role of Attachment in Relationship Satisfaction. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. The Attachment Behavioral System in Adulthood: Activation, Psychodynamics, and Interpersonal Processes. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 35, 56–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.I.; Sulaiman, W.S.W.; Mokhtar, D.M.; Adnan, H.A.; Abd Satar, J. Attachment Style among Female Adolescents: It’s Relationship with Coping Strategies and Life Satisfaction between Normal and Lesbian Female Adolescents. MOJPC Malays. Online J. Psychol. Couns. 2017, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-González, M.; Barrientos, J.; Cárdenas, M.; Espinoza, M.F.; Quijada, P.; Rivera, C.; Tapia, P. Romantic Attachment and Life Satisfaction in a Sample of Gay Men and Lesbians in Chile. Int. J. Sex. Health 2016, 28, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, S.J.; Sorrell, S.A.; Lefevor, G.T. Attachment, Minority Stress, and Health Outcomes among Conservatively Religious Sexual Minorities. J. Homosex. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plopa, M. Kwestionariusz Stylów Przywiązaniowych (KSP); Vizja Press & IT: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, F. The Costs of Being “Different”: Sexual Identity and Subjective Wellbeing over the Life Course. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 127, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejakovich, T.; Flett, R. “Are You Sure?”: Relations between Sexual Identity, Certainty, Disclosure, and Psychological Well-Being. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2018, 22, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Wiseman, M.C.; DeBlaere, C.; Goodman, M.B.; Sarkees, A.; Brewster, M.E.; Huang, Y.-P. LGB of Color and White Individuals’ Perceptions of Heterosexist Stigma, Internalized Homophobia, and Outness: Comparisons of Levels and Links. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 38, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitzel, L.R.; Smith, N.G.; Obasi, E.M.; Forney, M.; Leventhal, A.M. Perceived Distress Tolerance Accounts for the Covariance between Discrimination Experiences and Anxiety Symptoms among Sexual Minority Adults. J. Anxiety Disord. 2017, 48, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Björkenstam, C.; Björkenstam, E.; Andersson, G.; Cochran, S.; Kosidou, K. Anxiety and Depression among Sexual Minority Women and Men in Sweden: Is the Risk Equally Spread Within the Sexual Minority Population? J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.K.; Emerson, A.M. A Review of Lesbian Depression and Anxiety. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 2004, 15, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.E.; Salway, T.; Tarasoff, L.A.; MacKay, J.M.; Hawkins, B.W.; Fehr, C.P. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety among Bisexual People Compared to Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Graham, L.F.; Aronson, R.E.; Nichols, T.; Stephens, C.F.; Rhodes, S.D. Factors Influencing Depression and Anxiety among Black Sexual Minority Men. Depress. Res. Treat. 2011, 1, 587984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematy, A.; Oloomi, M. The Comparison of Attachment Styles among Iranian Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual and Heterosexual People. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2016, 28, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerymski, R. Influence of the Sex Reassignment on the Subjective Well-Being of Transgender Men–Results of the Pilot Study and Discussion about Future Research. Przegląd Seksuologiczny 2017, 16, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | All participants | 24.50 | 6.94 |

| Cisgender men | 24.77 | 7.35 | |

| Cisgender women | 24.23 | 6.50 | |

| Homosexual individuals | 23.98 | 6.47 | |

| Heterosexual individuals | 26.20 | 7.82 | |

| Bisexual and pansexual individuals | 23.00 | 6.16 | |

| Asexual individuals | 22.00 | 2.16 | |

| n | % | ||

| Gender identity | Cisgender men | 211 | 50.97% |

| Cisgender women | 203 | 49.03% | |

| Sexual orientation | Homosexual individuals | 215 | 51.93% |

| Heterosexual individuals | 130 | 31.40% | |

| Bisexual and pansexual individuals | 65 | 15.70% | |

| Asexual individuals | 4 | 0.97% | |

| LGBTQ+ | Heterosexual | t (412) | p | LLCI | ULCI | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||||

| Secure attachment | 41.77 | 9.43 | 42.45 | 9.68 | −0.67 | 0.500 | −2.659 | 1.300 | 0.07 |

| Anxious ambivalent attachment | 34.75 | 12.38 | 28.45 | 12.07 | 4.84 | <0.001 | 3.746 | 8.862 | 0.52 |

| Anxious avoidant attachment | 21.92 | 9.35 | 19.19 | 9.39 | 2.75 | 0.006 | 0.782 | 4.679 | 0.29 |

| Anxiety | 51.53 | 10.47 | 47.83 | 10.68 | 3.31 | 0.001 | 1.504 | 5.891 | 0.35 |

| Life satisfaction | 18.28 | 6.51 | 21.03 | 6.19 | −4.05 | <0.001 | −4.083 | −1.415 | 0.43 |

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure attachment | 41.77 | 9.43 | - | |||

| Anxious ambivalent attachment | 34.75 | 12.38 | −0.25 *** | - | ||

| Anxious avoidant attachment | 21.92 | 9.35 | −0.72 *** | 0.51 *** | - | |

| Anxiety | 51.53 | 10.47 | −0.35 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.46 *** | - |

| Life satisfaction | 18.28 | 6.51 | 0.37 *** | −0.50 *** | −0.42 *** | −0.71 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kardasz, Z.; Gerymski, R.; Parker, A. Anxiety, Attachment Styles and Life Satisfaction in the Polish LGBTQ+ Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146392

Kardasz Z, Gerymski R, Parker A. Anxiety, Attachment Styles and Life Satisfaction in the Polish LGBTQ+ Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(14):6392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146392

Chicago/Turabian StyleKardasz, Zofia, Rafał Gerymski, and Arkadiusz Parker. 2023. "Anxiety, Attachment Styles and Life Satisfaction in the Polish LGBTQ+ Community" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 14: 6392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146392