Learning to Live with HIV: The Experience of a Group of Young Chilean Men

Abstract

:1. Introduction

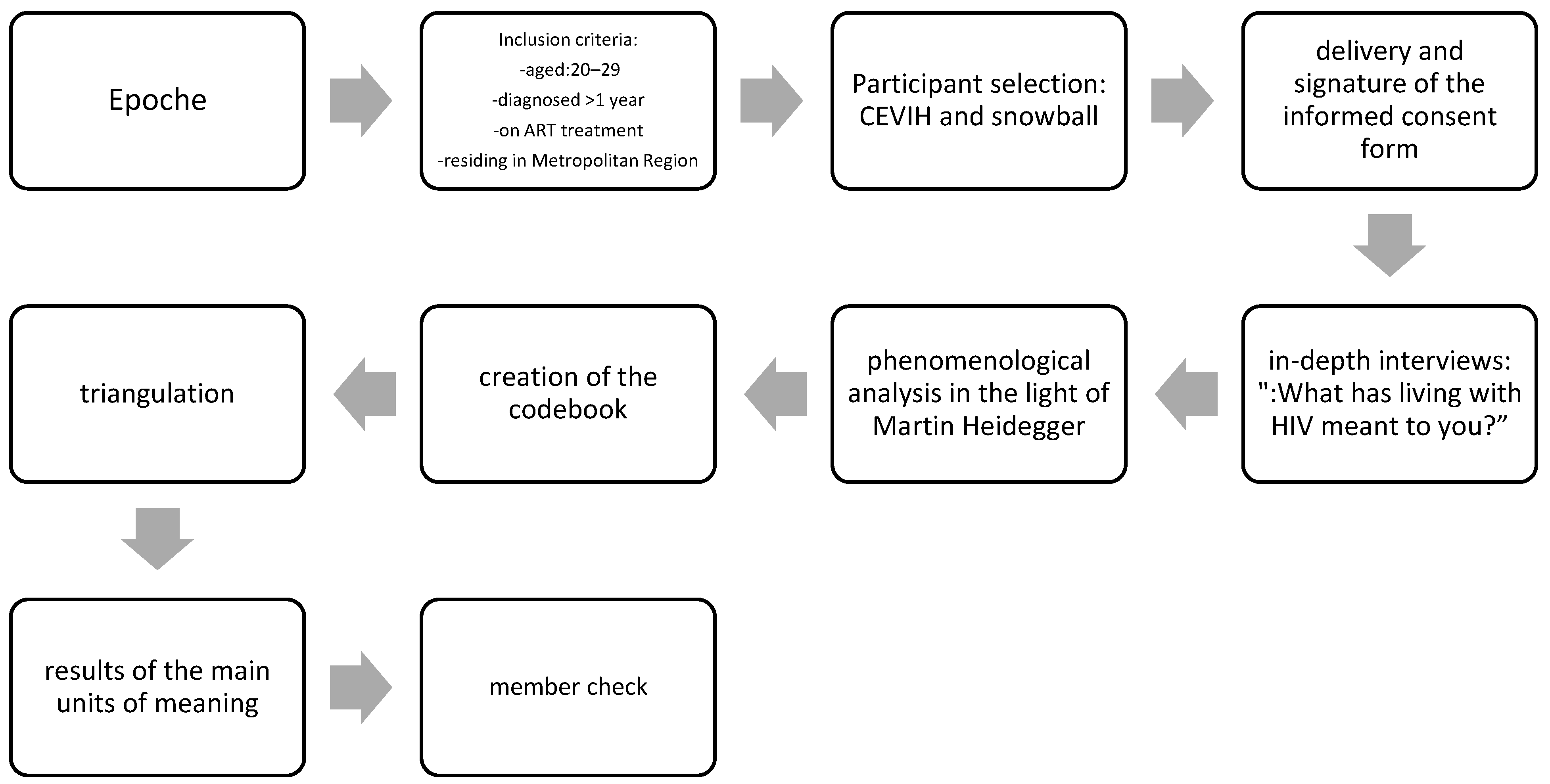

2. Method

3. Results

YPLHIV: “It didn’t exist in my reality, in my reality there was never going to be HIV, there was never going to be me having any sexually transmitted disease…”

YPLHIV: “… and at a certain moment I found myself, as if I was alone… with my mother’s prejudices a little bit…not anymore…but at that moment I was alone…”

YPLHIV: “At some point, they even wanted me to keep away from the family, you know, and that’s how you stop being my son…which is very hard”.

YPLHIV: “…getting to know someone and feeling something more for that person…and having to tell them and being rejected, maybe that has been one of my…fears…”

YPLHIV: “…first of all, I blamed myself a lot for being irresponsible and all that…”

YPLHIV: “For me it’s still the issue of…finding a partner or being with someone, for me it’s still stressful…”

YPLHIV: “Having to assume that I was not well, it was hard, and I decided to go about taking that option of the psychologist.”

YPLHIV: “I…I was interested in taking advantage of the space I had to be able to educate other people about sexual rights, because I find that in Chile there is a great lack…”.

YPLHIV: “I feel like the peer support has been all like…like today I can be sitting here with you and if someone hears me that I have HIV I don’t care…”

YPLHIV: “Living with HIV, as I said, was like a new beginning, a reaffirmation of my self-esteem, my self-love, that I had to take care of myself because it made me feel vulnerable…”

YPLHIV: “Well, my mother is still worried…”.

YPLHIV: “I never realized…I realized after I had it, my sexual ignorance about the whole thing…everything about the disease…”

YPLHIV: “…I knew him for about six months or so, and after three months I kind of told him, and it was like hey, I must tell you something, I live with HIV, so he told me…You know what? I can’t be with you…”

YPLHIV: “Without treatment…I mean what should have taken me one or two months, took me six months, and it was horrible because it was like: Hey! How horrible is this situation, having to go around, having to go around like chasing other people so I could get treatment…”?

YPLHIV: “…I have already changed at least four times my doc…virologist, and I don’t know, I haven’t felt much continuity either, the only continuous thing I have in my process are my pills…”.

YPLHIV: “…but I didn’t care about infecting someone else either…”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNAIDS. El SIDA en Cifras; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.unaids.org/es/whoweare/about (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile. Resultados Confirmación de Infección Por VIH. Chile, 2010–2018, 2019. Available online: https://www.ispch.cl/sites/default/files/BoletinVI-final_2019.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- MINSAL. Informe de ONUSIDA 2019: El 87% de las Personas Que Viven con VIH han Sido Diagnosticadas. Servicio de Salud de Magallanes. Available online: https://www.saludmagallanes.cl/cms/2019/07/17/informe-de-onusida-2019-el-87-de-las-personas-que-viven-con-vih-en-chile-han-sido-diagnosticadas/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Campillay, M.; Monárdez, M. Estigma y Discriminación En Personas Con VIH/SIDA, Un Desafío Ético Para Los Profesionales Sanitarios. In Revista de Bioética y Derecho; SciELO Espana: Barcelaona, Spain, 2019; pp. 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hosek, S.; Lemos, D.; Harper, G.; Telander, K. Evaluating the Acceptability and Feasibility of Project ACCEPT: An Intervention for Youth Newly Diagnosed with HIV. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2012, 23, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ONUSIDA. Claves Para Entender El Enfoque de Acción Acelerada. Poner Fin a La Epidemia de SIDA Para 2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/201506_JC2743_Understanding_FastTrack_es.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Heidegger, M. Tiempo y Ser; Heideggeriana: Todtnauberg, Germany, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C.; Vargas, I. Le Fenomenología de Husserl y Heidegger. 2017. Available online: http://rua.ua.es/dspace/handle/10045/69271 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Noreña, A.; Moreno, N.; Rojas, J.; Rebolledo, D. Aplicabilidad de Los Criterios de Rigor y Éticos En La Investigación Cualitativa. Aquichan 2012, 12, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch, L. Reconceptualizing the Member Check Interview. IJQM 2013, 12, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Salud, M. Plan Nacional de Prevención y Control Del VIH/SIDA e ITS. 2020. Available online: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Plan-Nacional-VIH-SIDA-e-ITS-2018-2019-ADENDA-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Mbuagbaw, L.; Ye, C.; Thabane, L. Motivational Interviewing for Improving Outcomes in Youth Living with HIV. Cochreane Libr. 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías, C.; Isalgué, M.; Mercedes, N.; Acosta, J. Enfoque Psicológico Para El Tratamiento de Personas Que Viven Con VIH/Sida. Rev. Inf. Cient. 2018, 97, 660–670. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.; Chauncey, S.; Tobey, L. The Social Support Networks of Gay Men with AIDS. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, P.; Simoni, J.; Bordeaux, L. Peer Support to Promote Medication Adherence among People Living with HIV/AIDS: The Benefits to Peers. Soc. Work Health Care 2007, 45, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, D.; Lovich, R.; Walker, D.; Burdock, T.; Ronan, A.; Ameyan, W.; Hatane, L. Providing Peer Support for Adolescents and Young People Living with HIV. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.27 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Bhana, A.; McKay, M.; Mellins, C.; Petersen, I.; Bell, C. Family-Based HIV Prevention, and Intervention Services for Youth Living in Poverty-Affected Contexts: The CHAMP Model of Collaborative, Evidence-Informed Programme Development. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2010, 13, S8-S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud, M. Fija Normas Sobre Información, Orientación y Prestaciones En Materia de Regulación de La Fertilidad. 2010. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1010482 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Belmar, J.; Stuardo, V. Adherencia al Tratamiento Anti-Retroviral Para El VIH/SIDA En Mujeres: Una Mirada Socio-Cultural. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2017, 34, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hierrezuelo, N.; Fernández, P.; Portuondo, Z. Estigma y VIH/Sida En Trabajadores de La Salud. Rev. Cubana. Hig. Epidemiol. 2020, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, V.; Clatworthy, J.; Harding, R.; Whetham, J. Measuring Quality of Life among People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review of ReviewsMeasuring Quality of Life among People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Units of Meaning | Literal Quotation | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Vision of HIV as something alien | “You never thought you could touch him” | There is still a lack of knowledge among young people on HIV issues, due to the absence of comprehensive sexual education that should be taught at school. |

| Lack of Sex Education | “…they never talked about a condom, they never talked about anything…” “…I realized after I had it, my sexual ignorance of all issues, everything that can ward off the disease…” | |

| Feeling of Loneliness | “…This disease, when you find out [you have it] brings you a…a very great feeling of loneliness…” | HIV diagnosis has negative mental repercussions on both young people and their families; therefore, it is critical to integrate personal and family psychological support into the HIV program. |

| Feelings of Anguish, Sadness, and Guilt | “First mental chaos that I experienced…I began to feel guilty of my illness, understand?” | |

| About Family Concerns | “Well, my mom to this day is kind of worried…” | |

| Little Family Acceptance | “The thing is that three months after I told my mother that I was living with HIV and I was her oldest child and only male child, huh…I think that caused her a lot…a lot of psychological suffering…or serious grief.” | |

| Empowerment to Educate and Support Other Youth | “…I mean I totally went from super shy, a super introvert and everything, now I feel super powerful…for so many years I saw it was so bad for me, and now I feel that it did nothing bad to me, nothing serious…and it turns your way of seeing life upside down, so I feel empowered, so powerful that I can handle everything…” | Empowerment in a chronic disease is fundamental in the motivation for self-care and consequently viral suppression. |

| Importance of Peer Support | “I feel that the peer support has been all like…as if today I can be sitting here with you and if someone hears that I have HIV, I don’t care, and I also take pictures and give them visibility…” | The creation of peer groups favors the acceptance of the disease. |

| Episodes of Discrimination by 3rd Parties | “…It happened to me that…people I was pseudo dating rejected me for having the condition…” | At present, young people continue to be victims of discrimination by partners, friends, and health personnel. |

| Fear of Rejection | “I don’t know how…to be meeting someone and feel something more for that person…and having to tell them and have them reject me, maybe that has been like my…fear…” | Young people are afraid to disclose their diagnosis to family members and partners for fear of rejection. |

| Lack of Protection of the Health System | “…how horrible this situation, having to walk as well as chasing other people so they can do the treatment” | Some young people are unhappy with the cumbersome process they must go through to receive antiretroviral therapy. |

| Lack of Continuity in Health Care | “…They have changed my doctor three times…at that time it was a sensitive issue for me…” | The continuous change of the treating physician that the young people experience is perceived as a difficulty in the continuity of their care. |

| Self-knowledge and Self-Love | “…so that’s why I’m telling you, it’s really no joke that this issue empowered me and gave me a self-love that I didn’t have before…” | When young people accept their disease and adhere to their treatment, they improve their self-esteem. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calderón Silva, M.B.; Ferrer Lagunas, L.M.; Cianelli, R. Learning to Live with HIV: The Experience of a Group of Young Chilean Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176700

Calderón Silva MB, Ferrer Lagunas LM, Cianelli R. Learning to Live with HIV: The Experience of a Group of Young Chilean Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(17):6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176700

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalderón Silva, Macarena Belén, Lilian Marcela Ferrer Lagunas, and Rosina Cianelli. 2023. "Learning to Live with HIV: The Experience of a Group of Young Chilean Men" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 17: 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176700

APA StyleCalderón Silva, M. B., Ferrer Lagunas, L. M., & Cianelli, R. (2023). Learning to Live with HIV: The Experience of a Group of Young Chilean Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(17), 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20176700