Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in South Africa: Prevalence and Perceptions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

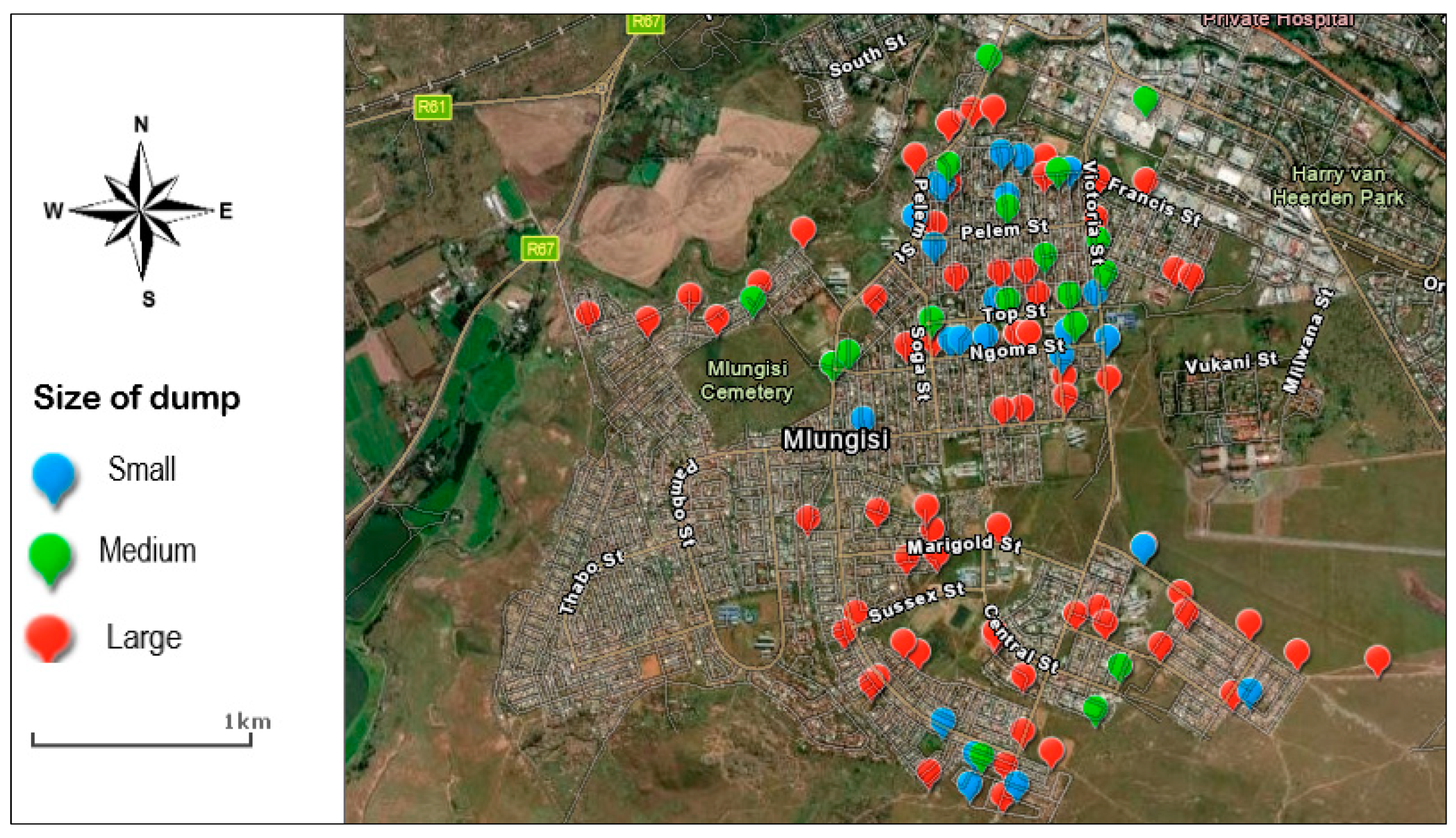

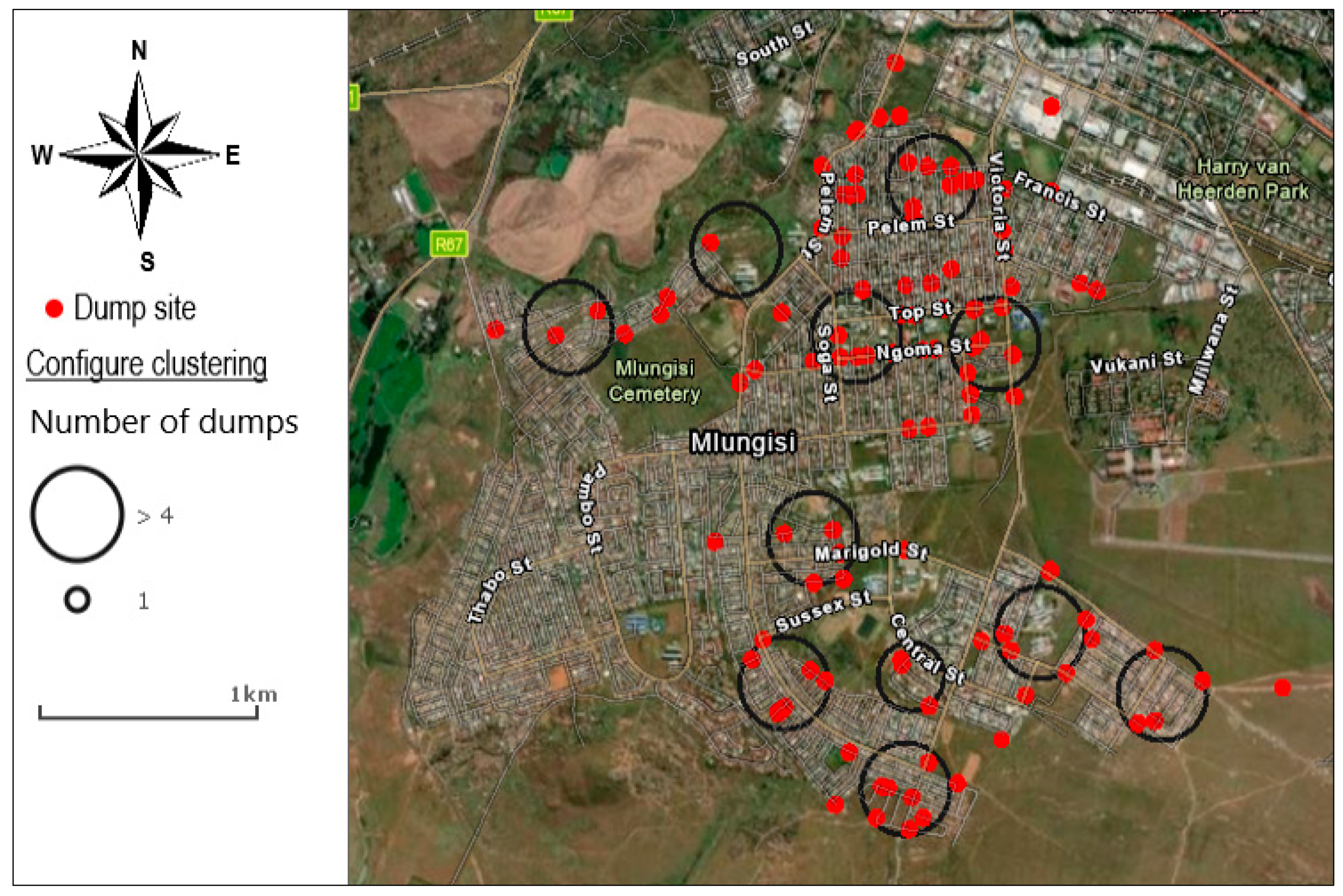

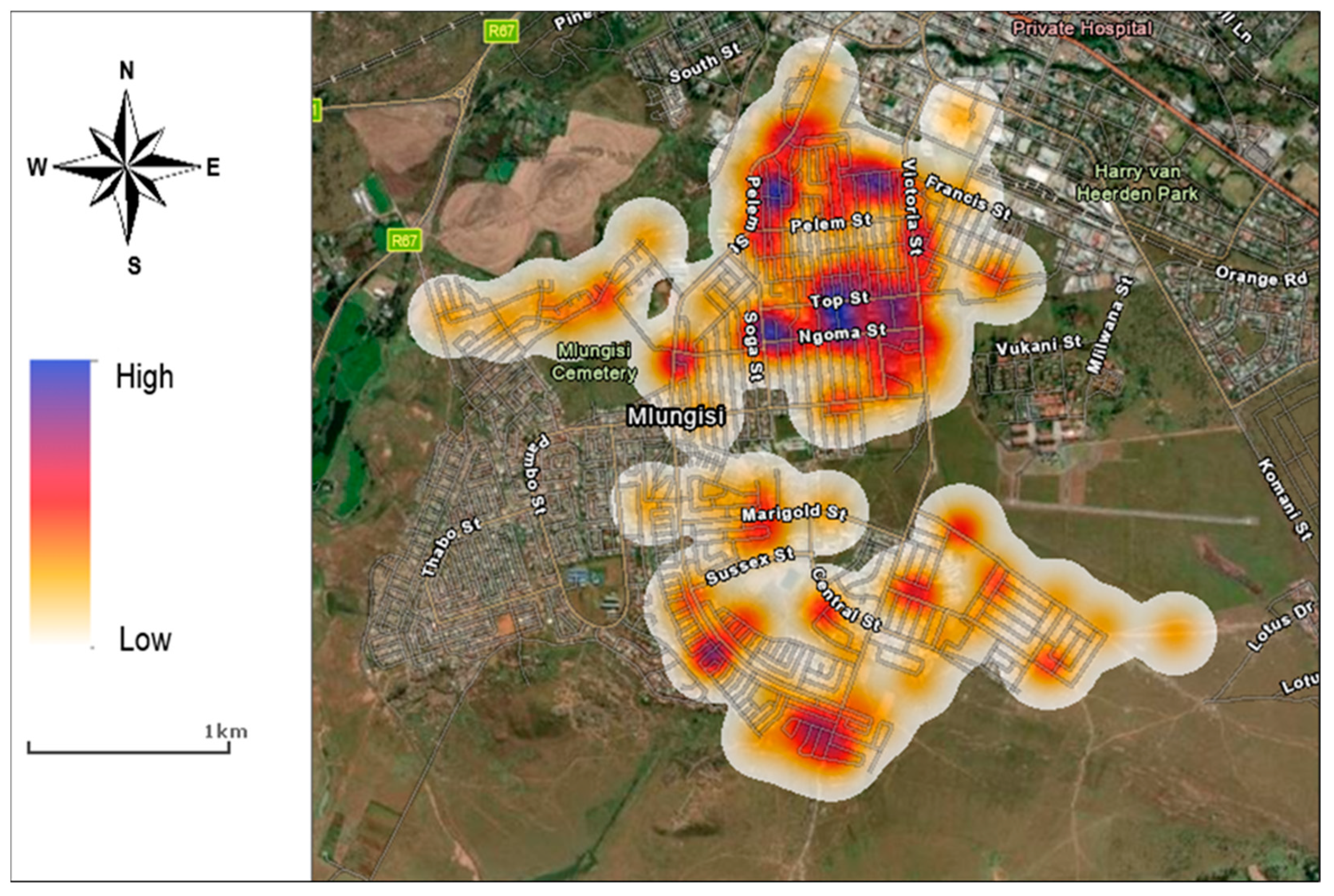

3.1. Abundance, Distribution, Size and Composition of Illegal Solid-Waste Dumps

3.2. The Socio-Demographic Profile of the Respondents

3.3. Solid-Waste-Disposal Practices

3.4. Factors Contributing to Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping

3.5. Perceived Impacts of Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping

3.6. Potential Interventions Reported by the Respondents

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, X.; Dong, L.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X. Polycentric governance in waste management: A mechanism analysis of actors’ behavior evolution at the community level. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 191, 106879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.C.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/30317 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- da Silva, C.L.; Weins, N.; Potinkara, M. Formalizing the informal? A perspective on informal waste management in the BRICS through the lens of institutional economics. Waste Manag. 2019, 99, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharas, H. The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries; Working Paper No. 285; OECD Development Centre: Paris, France; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dev/44457738.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V. Waste mismanagement in developing countries: A review of global issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyobuhungiro, R.V.; Schenck, C. Exploring community perceptions of illegal dumping in Fisantekraal using participatory action research. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mngomezulu, S.K.; Mbanga, S.; Adeniran, A.A.; Soyez, K. Factors influencing solid waste management practices in Joe Slovo Township, Nelson Mandela Bay. J. Public Adm. 2020, 55, 400–411. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-jpad-v55-n3-a11 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Triassi, M.; Alfano, R.; Illario, M.; Nardone, A.; Caporale, O.; Montuori, P. Environmental pollution from illegal waste disposal and health effects: A review on the “Triangle of Death”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1216–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubanza, N.S.; Simatele, D. Social and environmental injustices in solid waste management in sub-Saharan Africa: A study of Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 866–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medgyesi, D.N.; Brogan, J.M.; Sewell, D.K.; Creve-Coeur, J.P.; Kwong, L.H.; Baker, K.K. Where children play: Young child exposure to environmental hazards during play in public areas in a transitioning internally displaced persons community in Haiti. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzawanda, B.; Moyo, G.A. Challenges associated with household solid waste management (swm) during COVID-19 lockdown period: A case of ward 12 Gweru city, Zimbabwe. Environ. Monit. Assess 2022, 194, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongcula, V.; Jaja, I.; Nhundu, K.; Zhou, L. Prevalence, perception and implication of solid waste in cattle slaughtered in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 8, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubanza, N.S.; Simatele, M.D. Sustainable solid waste management in developing countries: A study of institutional strengthening for solid waste management in Johannesburg, South Africa. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Ismail, S.A.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.P. Urban solid waste management in the developing world with emphasis on India: Challenges and opportunities. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio-Technol. 2015, 14, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Statistics South Africa 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Rodseth, C.; Notten, P.; von Blottnitz, H. A revised approach for estimating informally disposed domestic waste in rural versus urban South Africa and implications for waste management. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2020, 116, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsheleza, V.; Ndhleve, S.; Kabiti, H.M.; Musampa, C.M.; Nakin, M.D.V. Vulnerability of growing cities to solid waste-related environmental hazards: The case of Mthatha, South Africa. Jamba 2019, 11, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, L.K.; Kapwata, T.; Oelofse, S.; Breetzke, G.; Wright, C.Y. Waste disposal practices in low-income settlements of South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 18, 8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niyobuhungiro, R.V.; Schenck, C.J. A global literature review of the drivers of indiscriminate dumping of waste: Guiding future research in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2022, 39, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Shackleton, C.M.; Van Staden, F.; Selomane, O.; Masterson, V.A. Green apartheid: Urban green infrastructure remains unequally distributed across income and race geographies in South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, R.; Grobler, L.; Blaauw, P.; Nell, C. Reasons for littering: Social constructions from lower income communities in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, J.M.M. Household waste management practices and challenges in a rural remote town in the Hantam Municipality in the Northern Cape, South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2011; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Ward, C.D. Livelihoods and Natural Resource Use along the Rural-Urban Continuum. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maroyi, A. Traditional uses of wild and tended plants in maintaining ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes of the Eastern Cape province in South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECSECC—Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council. Available online: https://ecsecc.org/default.aspx (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Damba-Hedrik, N. The Municipality Is Not Collecting Our Rubbish, but They Threaten to Arrest Us If We Dump. GroundUp. 4 April 2019. Available online: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/municipality-not-collecting-our-rubbish-they-threaten-arrest-us-if-we-dump/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- eNCA. Komani Shutdown|Residents Angry over Lack of Services. 17 February 2023. Available online: https://www.enca.com/news/komani-shutdown-protesters-force-businesses-close#google_vignette (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries. National Waste Management Strategy 2020; Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Noble, H. Bias in Research. Evid. Based Nurs. 2014, 17, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, O.O.; Obafemi, T.H.; Obiajunwa, P.O.; Obiajunwa, C.J.; Obisanya, O.A.; Odanye, O.H.; Odeleye, A.O. Solid waste management and health hazards associated with residence around open dumpsites in heterogeneous urban settlements in southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 1313–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineo, H.; Rydin, Y. Cities, Health and Well-Being; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Polasi, L. Factors associated with illegal dumping in the Zondi area, city of Johannesburg, South Africa. In Proceedings of the WasteCon 2018, Emperors Palace, Kempton Park, Johannesburg, South Africa, 15–19 October 2018; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10204/10511 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Gonçalves, A.T.T.; Moraes, F.T.F.; Marques, G.L.M.; Lima, J.P.; da Silva Lima, R. Urban solid waste challenges in the BRICS countries: A systematic literature review. Rev. Ambient. Água Interdiscip. J. Appl. Sci. 2018, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Steimer, N. Subjective reasons for littering: A self-serving attribution bias as justification process in an environmental behaviour model. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2017, 73, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutumbi, U.; Thondhlana, G.; Ruwanza, S. Co-designed interventions yield significant electricity savings among low-income households in Makhanda South Africa. Energies 2022, 15, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlam, G.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, M.; Kumar, R. Trash on the menu: Patterns of animal visitation and foraging behaviour at garbage dumps. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 2322–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z. Environmental justice in South Africa: Tools and trade-offs. Soc. Dyn. 2009, 35, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Abson, D.J.; Von Wehrden, H.; Dorninger, C.; Klaniecki, K.; Fischer, J. Reconnecting with Nature for Sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirchio, S.; Passiatore, Y.; Panno, A.; Cipparone, M.; Carrus, G. The effects of contact with nature during outdoor environmental education on students’ wellbeing, connectedness to nature and pro-sociality. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, S. Integrating the Informal Sector into the South African Waste and Recycling Economy in the Context of Extended Producer Responsibility. Available online: https://docslib.org/doc/8771056/integrating-the-informal-sector-into-the-south-african-waste-and-recycling-economy-in-the-context-of-extended-producer-responsibility (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Joel, A.B.; Fansen, T. Pattern and Disposal Methods of Municipal Waste Generation in Kaduna Metropolis of Kaduna State, Nigeria. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 1, 1–12. Available online: http://www.ijern.com/journal/December-2013/55.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Department of Environmental Affairs. National Waste Information Baseline Report; Department of Environmental Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Plastics, S.A. SA Releases Latest Recycling Figures. 2019. Available online: https://www.plasticsinfo.co.za/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Moreno-Sanchez, R.D.P.; Maldonado, J.H. Surviving from garbage: The role of informal waste-pickers in a dynamic model of solid-waste management in developing countries. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.M. Waste pickers and cities. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter, A.; Ahsan, M.; Marbach, M.; Zurbrügg, C. Impacts of policy and market incentives for solid waste recycling in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Waste Manag. 2015, 39, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmarsh, L.E.; Haggar, P.; Thomas, M. Waste reduction behaviors at home, at work, and on holiday: What influences behavioral consistency across contexts? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, J. Environmental regulation of households: An empirical review of economic and psychological factors. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Household Socio-Economic Factors | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender (%) of household head | |

| Female | 62 |

| Male | 38 |

| Mean age (±SD) (in years) of household head | 54 ± 16 |

| Mean (±SD) household size | 5 ± 3 |

| Education level (%) | |

| No education | 1 |

| Primary school | 14 |

| Secondary school | 65 |

| Tertiary | 20 |

| Average monthly income (ZAR) (%) | |

| <2000 | 51 |

| 2001–6000 | 30 |

| 6001–15,000 | 9 |

| 15,001–30,000 | 7 |

| >30,000 | 3 |

| Mean (±SD) length of stay | 43 ± 23 |

| Disposal Method | Proportion (%) of Respondents |

|---|---|

| Open disposal | 36 |

| Burning | 22 |

| Backyard disposal | 10 |

| Landfill | 5 |

| Recycling | 1 |

| Others | 26 |

| Reported Factor | Proportion (%) of Respondents |

|---|---|

| Poor waste collection services | 48 |

| Lack of care | 35 |

| Lack of resources | 7 |

| Lack of awareness of impacts | 4 |

| Municipal strikes | 3 |

| Others | 4 |

| Impacts | Proportion (%) of Respondents |

|---|---|

| Loss of property value | 70 |

| Visual pollution | 69 |

| Poor air quality | 25 |

| Livestock sickness and deaths | 19 |

| Health hazards to people | 14 |

| Business impacts | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngalo, N.; Thondhlana, G. Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in South Africa: Prevalence and Perceptions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186750

Ngalo N, Thondhlana G. Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in South Africa: Prevalence and Perceptions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(18):6750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186750

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgalo, Nobomi, and Gladman Thondhlana. 2023. "Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in South Africa: Prevalence and Perceptions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 18: 6750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186750