Predictors of Unmet Healthcare Needs during Economic and Health Crisis in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

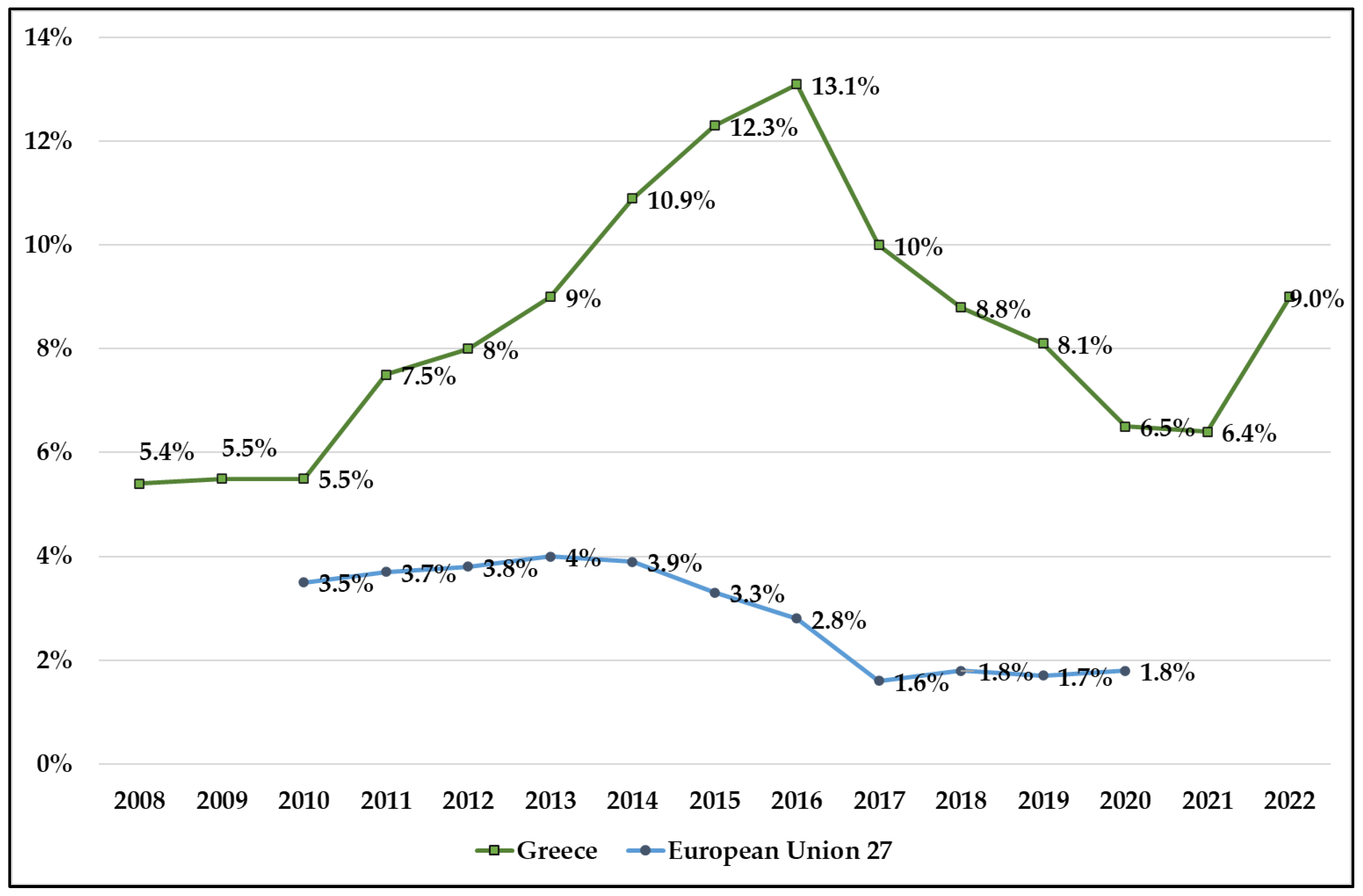

3.1. Unmet Medical Health Needs in Greece versus EU27

3.2. Unmet Dental Health Needs in Greece vs. EU27

3.3. Greece’s Unmet Medical Health Needs by Region

3.4. Unmet Medical Health Needs in Greece versus EU27 by Income Quintile

3.5. Greece’s Unmet Medical Health Needs by Occupational Status

3.6. Comparative Effect Sizes of Key Variables Predictive of Unmet Needs

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez, S.; Mason, A.; Gutacker, N.; Kasteridis, P.; Santos, R.; Rice, N. Need, demand, supply in health care: Working definitions, and their implications for defining access. Health Econ. Policy Law 2023, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi-Lari, M.; Packham, C.; Gray, D. Need for redefining needs. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 21, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J. Taxonomy of social need. In Problems and Progress in Medical Care: Essays on Current Research; 7th series; Gordon, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1972; pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH). Report on Access to Health Services in the European Union; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-11/015_access_healthservices_en_0.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Eurostat. Methodological Issues in the Analysis of the Socioeconomic Determinants of Health Using EU-SILC Data, in Eurostat Methodologies and Working Papers; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Accessibility: Affordability, Availability and Use of Services—Figure 7.1. Unmet Needs for Medical Examination Due to Financial, Geographic or Waiting Time Reasons, 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://stat.link/63hqkl (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Eurofound; Ahrendt, D.; Consolini, M.; Mascherini, M.; Sándor, E. Fifth Round of the Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Survey: Living in a New Era of Uncertainty; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2806/190361 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Accessibility: Affordability, Availability and Use of Services—Figure 7.2. Unmet Needs for Dental Examination Due to Financial, Geographic or Waiting Time Reasons, 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://stat.link/5k7zg0 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- OECD. A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health; OECD Health Policy Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kentikelenis, A. Structural adjustment and health: A conceptual framework and evidence on pathways. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 187, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurostat. Main GDP Aggregates per Capita. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NAMA_10_PC/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Eurostat. Health Care Expenditure by Financing Scheme. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_sha11_hf/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Kim, J.; Kim, T.H.; Park, E.C.; Cho, W.H. Factors influencing unmet need for health care services in Korea. Asia Pac. J. Public Health. 2015, 27, NP2555–NP2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronksley, P.E.; Sanmartin, C.; Quan, H.; Ravani, P.; Tonelli, M.; Manns, B.; Hemmelgarn, B.R. Association between chronic conditions and perceived unmet health care needs. Open Med. 2012, 6, e48. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Park, E.C. The effect of economic participatory change on unmet needs of health care among Korean adults. Health Policy Manag. 2015, 25, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahelma, E.; Martikainen, P.; Laaksonen, M.; Aittomäki, A. Pathways between socioeconomic determinants of health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, S.; Masseria, C. Unmet need as an indicator of health care access. Eurohealth 2009, 15, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mielck, A.; Kiess, R.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Stirbu, I.; Kunst, A.E. Association between forgone care and household income among the elderly in fiveWestern European countries–analyses based on survey data from the SHARE-study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, K.; De Norre, B. Perception of Health and Access to Health Care in the EU-25 in 2007. Eurostat Statistics in Focus 24/2009; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2009; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3433488/5280869/KS-SF-09-024-EN.PDF.pdf/f4f4f956-eafb-49f6-a52a-4a22d602433c (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Hernández-Quevedo, C.; Masseria, C.; Mossialos, E. Methodological Issues in the Analysis of the Socioeconomic Determinants of Health Using EU-SILC Data; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2010; ISBN 978-92-79-16753-3. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, A.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. The attack on universal health coverage in Europe: Recession, austerity and unmet needs. Eur. J. Public Health. 2015, 25, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Zolyomi, E.; Kalavrezou, N.; Matsaganis, M. The Impact of the Financial Crisis on Unmet Needs for Healthcare; European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Database. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Eurostat Database. Self-Reported Unmet Needs for Health Care By Sex, Age, Specific Reasons and Educational Attainment Level. 2021. Available online: hlth_ehis_un1e (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Eurostat. Self-Reported Unmet Needs for Medical Examination by Main Reason Declared and NUTS 2 Regions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_silc_08_r/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Law 4368/2016. Measures to Speed Up Government Work and Other Provisions. Government Gazette 21/A/21.2.2016 (Chapter Ε1, Article 33). Ministry of Health, Greece. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.gr/articles/health/anaptyksh-monadwn-ygeias/3999-prosbash-twn-anasfalistwn-sto-dhmosio-systhma-ygeias?fdl=10014 (accessed on 11 July 2023). (In Greek)

- Damaskinos, P.; Economou, C. Systems for the provision of oral health care in the black sea countries part 10: Greece. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2012, 11, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Damaskinos, P.; Koletsi-Kounari, H.; Economou, C.; Eaton, K.A.; Widström, E. The healthcare system and provision of oral healthcare in European Union member states. Part 4: Greece. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 220, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogos, C.; Papadopoulou, E.; Doukas, I.; Tsolaki, M. Regional Distribution Disparities of Healthcare Resources in Greece. EMSJ 2022, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrakos, G. Organization of Local Community Health Network During Infections Such as COVID-19. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism in the COVID-19 Era; Androniki, K., Stephen, J.H., Natalya, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Stirbu, I.; Roskam, A.J.R.; Schaap, M.M.; Menvielle, G.; Leinsalu, M.; Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eikemo, T.A.; Huisman, M.; Bambra, C.; Kunst, A.E. Health inequalities according to educational level in different welfare regimes: A comparison of 23 European countries. Soc. Health Illn. 2008, 30, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Borsboom, G.J.; Looman, C.; Bopp, M.; Burström, B.; Dzúrová, D.; Ekholm, O.; Klumbiene, J.; Lahelma, E.; et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in self-assessed health in 17 European countries between 1990 and 2010. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, L.; Glazier, R. Reasons for Self-Reported Unmet Healthcare Needs in Canada: A Population-Based Provincial Comparison. Healthc. Policy 2009, 5, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Pineault, R.; Hamel, M.; Roberge, D.; Kapetanakis, C.; Simard, B.; Prud’homme, A. Emerging organizational models of primary healthcare and unmet needs for care: Insights from a population-based survey in Quebec province. BMC Fam. Pract. 2012, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.; Astolfi, R. Health Spending Continues to Stagnate in Many OECD Countries; OECD Health Working Papers, No. 68; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altanis, P.; Economou, C.; Geitona, M.; Susan, G.; Mestheneos, E.; Triantafillou, J.; Petsetaki, E.; Kyriopoulos, J. Quality in and Equality of Access to Healthcare Services; Country Report for Greece; European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Minogiannis, P. Tomorrow’s public hospital in Greece: Managing health care in the post crisis era. Soc. Cohes. Dev. 2016, 7, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthappu, M.; Watson, R.; Watkins, J.; Williams, C.; Zeltner, T.; Faiz, O.; Ali, R.; Atun, R. Unemployment, public-sector healthcare expenditure and colorectal cancer mortality in the European Union: 1990–2009. Int. J. Public Health 2016, 61, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.; Reeves, A.; Stuckler, D. Unmet health need and unemployment during recession in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydsten, A.; Hammarström, A.; San Sebastian, M. Health inequalities between employed and unemployed in northern Sweden: A decomposition analysis of social determinants for mental health. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latsou, D.; Pierrakos, G.; Geitona, M. Health and unmet health needs of the unemployed in Greece. Arch. Hell. Med. 2021, 38, 642–650. [Google Scholar]

- Latsou, D.; Geitona, M. Predictors of physical and mental health among unemployed people in Greece. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Can People Afford to Pay for Health Care? New Evidence on Financial Protection in Europe; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311654 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Cavalieri, M. Geographical variation of unmet medical needs in Italy: A multivariate logistic regression analysis. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2013, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovic, N.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Simic, S.; Mladenovic, B. Predictors of unmet health care needs in Serbia; analysis based on EU-SILC data. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0187866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Liu, Q.; Fu, R.; Ma, J. Unmet healthcare needs, health outcomes, and health inequalities among older people in China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, M.J.A.; Chalkley, M.; Goddard, M. Defining and Measuring Unmet Need to Guide Healthcare Funding: Identifying and Filling the Gaps; Working Papers; Centre for Health Economics, University of York: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, G.; Grignon, M.; Hurley, J.; Wang, L. Here comes the SUN: Self-assessed unmet need, worsening health outcomes, and health care inequity. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H. Unmet healthcare needs and health status: Panel evidence from Korea. Health Policy 2016, 120, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicators | Unit | Year | Reference | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported unmet need for medical care (too expensive or too far to travel or waiting list) | Percentage | 2008–2022 | TESPM110 | Subjective view of a person’s need for examination or treatment, who did not receive it due to ‘financial reasons’, ‘waiting list’, or ‘too far to travel’ |

| Gender (female) | Number | 2013–2022 | DEMO_PJAN__custom_6646580 | |

| Gender (male) | Number | 2013–2022 | DEMO_PJAN__custom_6646561 | |

| Household out-of-pocket payment (private health expenditures) | Million euro | 2012–2021 | HLTH_SHA11_HPHF__custom_6647166 | Direct payment by households to health professionals, suppliers of pharmaceuticals, etc. |

| Government schemes and compulsory contributory healthcare financing schemes (public health expenditures) | Million euro | 2012–2021 | HLTH_SHA11_HPHF__custom_6647089 | Government expenditures for the provision of health services |

| Self-perceived health | Percentage | 2013–2022 | One question instrument assessing the general perceived health: “How is your health in general? Is it very good/good/fair/bad/very bad?” | |

| (Very good or good) | HLTH_SILC_01__custom_6646803 | |||

| (Fair) | HLTH_SILC_01__custom_6646814 | |||

| (Bad or very bad) | HLTH_SILC_01__custom_6646825 | |||

| People having a long-standing illness or health problem | Percentage | 2013–2022 | HLTH_SILC_04__custom_6647218 | Chronic morbidity duration of at least six months |

| Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem (some or severe) | Percentage | 2013–2022 | HLTH_SILC_12$DEFAULTVIEW | One question from the Global Activity Limitation Instrument (GALI) assessing the presence of long-standing activity limitation |

| Real GDP per capita in EUR | Number | 2008–2022 | SDG_08_10 | The average output of the economy per person measured in a base year |

| Employment rate | Percentage | 2009–2022 | TESEM010 | The percentage of employed persons in relation to the total population |

| Unemployment rate | Percentage | 2011–2022 | TPS00203 | The number of people unemployed as a percentage of the labor force |

| Unmet Medical Needs | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p-Value | |

| Female | 0.418 | 0.229 |

| Male | 0.280 | 0.433 |

| Private health expenditures | −0.682 * | 0.014 |

| Public health expenditures | −0.765 ** | 0.004 |

| Self-perceived health: fair | 0.530 | 0.115 |

| Self-perceived health: bad/very bad | 0.786 ** | 0.007 |

| Self-perceived health: very good/good | −0.793 ** | 0.006 |

| Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem: some/severe | 0.681 * | 0.030 |

| Real GDP per capita | −0.632 * | 0.012 |

| Employment rate | −0.615 * | 0.019 |

| Unemployment rate | 0.599 * | 0.040 |

| Adjusted R2 | Predicted Factors | Dependent Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | t | p Value | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| 41.2% | Private health expenditures | (Constant) | 31.921 | 7.860 | 4.061 | 0.002 | 14.408 | 49.435 |

| Unmet medical needs | −3.832 | 1.298 | −2.953 | 0.014 | −6.724 | −0.941 | ||

| 54.4% | Public health expenditures | (Constant) | 16.580 | 2.134 | 7.771 | 0.001 | 11.826 | 21.334 |

| Unmet medical needs | −0.754 | 0.201 | −3.758 | 0.004 | −1.201 | −0.307 | ||

| 39.6% | Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem: some/severe | (Constant) | −34.598 | 16.760 | −2.064 | 0.073 | −73.247 | 4.050 |

| Unmet medical needs | 1.859 | 0.708 | 2.627 | 0.030 | 0.227 | 3.491 | ||

| 57% | Self-perceived health: bad/very bad | (Constant) | 0.833 | 2.430 | 0.343 | 0.741 | −4.770 | 6.436 |

| Unmet medical needs | 0.966 | 0.269 | 3.596 | 0.007 | 0.346 | 1.585 | ||

| 58.3% | Self-perceived health: very good/good | (Constant) | 70.672 | 16.640 | 4.247 | 0.003 | 32.300 | 109.044 |

| Unmet medical needs | −0.807 | 0.219 | −3.683 | 0.006 | −1.313 | −0.302 | ||

| 35.3% | Real GDP per capita | (Constant) | 23.469 | 5.151 | 4.556 | 0.001 | 12.340 | 34.597 |

| Unmet medical needs | −0.001 | 0.000 | −2.939 | 0.012 | −0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 32.6% | Employment rate | (Constant) | 27.704 | 7.084 | 3.911 | 0.002 | 12.268 | 43.139 |

| Unmet medical needs | −0.325 | 0.120 | −2.702 | 0.019 | −0.586 | −0.063 | ||

| 29.5% | Unemployment rate | (Constant) | 3.720 | 2.345 | 1.586 | 0.144 | −1.506 | 8.946 |

| Unmet medical needs | 0.439 | 0.186 | 2.365 | 0.040 | 0.025 | 0.853 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pierrakos, G.; Goula, A.; Latsou, D. Predictors of Unmet Healthcare Needs during Economic and Health Crisis in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196840

Pierrakos G, Goula A, Latsou D. Predictors of Unmet Healthcare Needs during Economic and Health Crisis in Greece. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(19):6840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196840

Chicago/Turabian StylePierrakos, George, Aspasia Goula, and Dimitra Latsou. 2023. "Predictors of Unmet Healthcare Needs during Economic and Health Crisis in Greece" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 19: 6840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196840

APA StylePierrakos, G., Goula, A., & Latsou, D. (2023). Predictors of Unmet Healthcare Needs during Economic and Health Crisis in Greece. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19), 6840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196840