Effect of Different Frequencies of Dental Visits on Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scoping Review Question

2.2. Dental Caries

2.3. Periodontal Disease

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Search Strategy

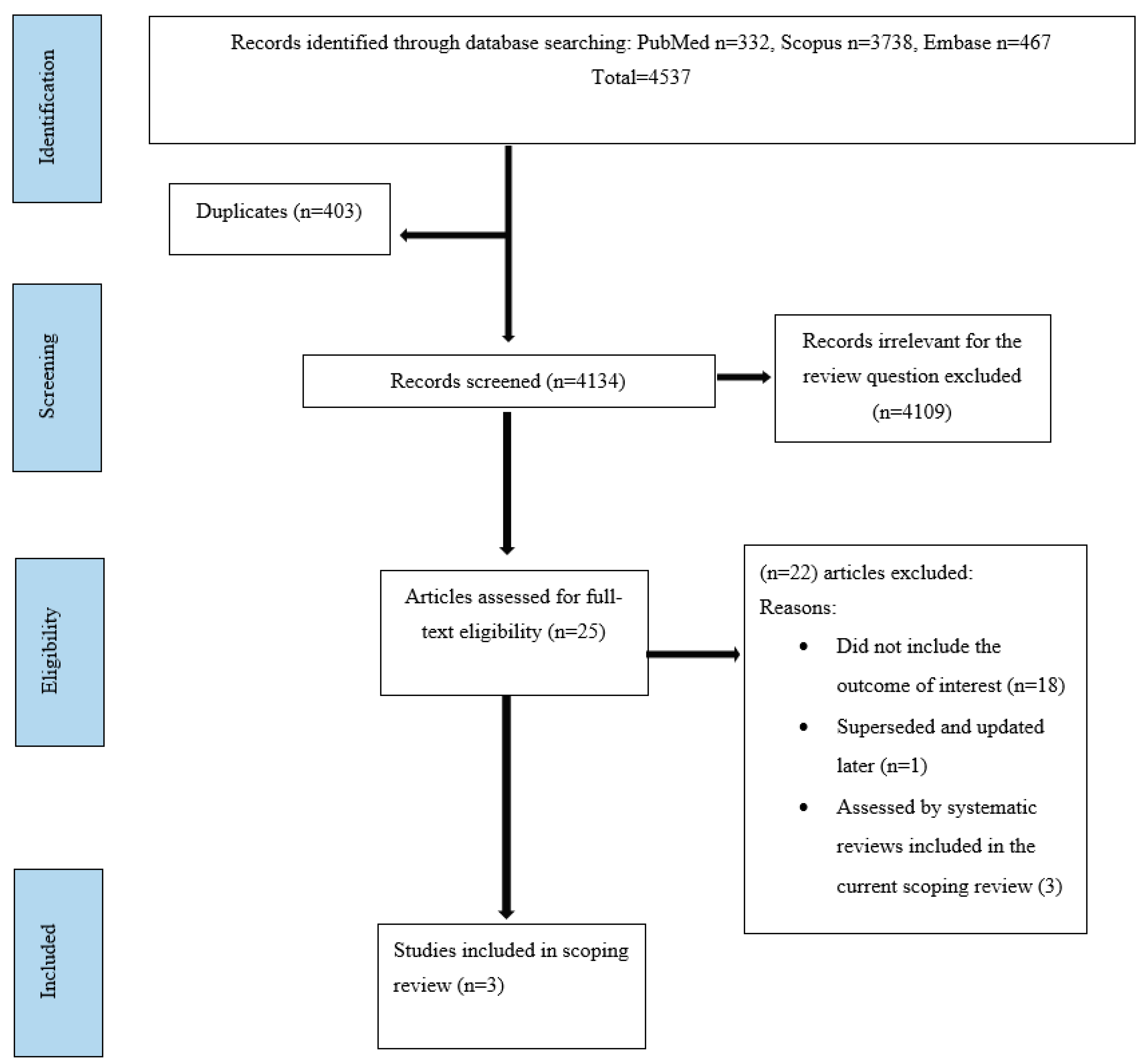

2.7. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Cochrane Systematic Review on Recall Intervals for Oral Health in Primary Care Patients

3.2. Cochrane Systematic Review on the Beneficial and Harmful Effects of Routine Scaling and Polishing (RSP) on Periodontal Health

3.3. Systematic Review on the Appropriate Recall Interval for Periodontal Maintenance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Research

- Further studies are warranted for children and adolescents, in particular well-designed RCTs and large cohort studies of sufficient duration with an adequate number of participants and adjusted for risk assessment, to reflect a true difference among the varying frequencies of dental visits in regards to the potential beneficial and harmful effects on oral health.

- It is recommended that patient-centred factors as well as economic aspects should be incorporated as outcome measures, and the type of interventions should be clearly specified in future studies.

- Future studies should also focus on developing more evidence-based, customized and appropriate recall intervals.

5.2. Implications for Practice

- The available body of evidence indicates that firm conclusions cannot be made about the potential beneficial or harmful effects of different frequencies of dental visits on dental caries or periodontal disease, including the common practice of encouraging patients to make six-monthly dental visits. In this context, oral health professionals are suggested to make individually tailored, customised and risk-based recommendations for the frequencies of dental visits rather than encouraging fixed or universal frequencies of dental visits.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-006148-4.

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Dahiya, M.; Bhandari, B.; Murray, C.J.; Marcenes, W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: A systematic review and meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beirne, P.; Forgie, A.; Clarkson, J.; Worthington, H.V. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2, Cd004346. [Google Scholar]

- Beirne, P.; Clarkson, J.E.; Worthington, H.V. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 4, Cd004346. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, P.; Worthington, H.V.; Clarkson, J.E.; Beirne, P.V. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD004346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, J.E.; Amaechi, B.T.; Ngo, H.; Bonetti, D. Recall, reassessment and monitoring. Monogr. Oral Sci. 2009, 21, 188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Amarasena, N.; Kapellas, K.; Skilton, M.R.; Maple-Brown, L.J.; Brown, A.; Bartold, M.; O’Dea, K.; Celermajer, D.; Jamieson, L.M. Factors Associated with Routine Dental Attendance among Aboriginal Australians. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Williams, S.M.; Broadbent, J.M.; Poulton, R.; Locker, D. Long-term dental visiting patterns and adult oral health. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocombe, L.A.; Broadbent, J.M.; Thomson, W.M.; Brennan, D.S.; Slade, G.D.; Poulton, R. Dental visiting trajectory patterns and their antecedents. J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstrøm, A.N.; Ekback, G.; Ordell, S.; Nasir, E. Long-term routine dental attendance: Influence on tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life in Swedish older adults. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2014, 42, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, L.; Harford, J. Financial burden of dental care among Australian children. Aust. Dent. J. 2014, 59, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chrisopoulos, S.; Luzzi, L.; Ellershaw, A. National Study of Adult Oral Health 2017–2018: Study design and methods. Aust. Dent. J. 2020, 65, S5–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Vujicic, M. Barriers to Dental Care Are Financial among Adults of all Income Levels. Health Policy Institute Research Brief. American Dental Association. 2019. Available online: https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/adaorganization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/hpi/hpibrief_0419_1.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Sheiham, A. Is there a scientific basis for six-monthly dental examinations? Lancet 1977, 2, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Advisory Committee on Oral Health. Healthy Mouths, Healthy Lives: Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2004–2013; Government of South Australia, on behalf of the Australian Health Ministers’ Conference: Adelaide, Australia, 2004; ISBN 0730893537.

- National Oral Health Promotion Clearing House. Oral Health Messages for the Australian Public. Findings of a national consensus workshop. Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral Health Monitoring Group. Healthy Mouths, Healthy Lives: Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024; Australian Government, COAG Health Council: Canberra, Australia, 2015; ISBN 978-0-646-94487-6.

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S.; Blanco, J.; Buchalla, W.; Carvalho, J.C.; Dietrich, T.; Dörfer, C.; Eaton, K.A.; Figuero, E.; Frencken, J.E.; Graziani, F.; et al. Prevention and control of dental caries and periodontal diseases at individual and population level: Consensus report of group 3 of joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, S85–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, P.A.; Riley, P.; Worthington, H.V.; Clarkson, J.E.; Boyers, D.; Beirne, P.V. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 10, CD004346. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, T.; Worthington, H.V.; Clarkson, J.E.; Beirne, P.V. Routine scale and polish for periodontal health in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD004625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, O.A.; Wehler, C.J.; Gibson, G.; Jurasic, M.M.; Jones, J.A. Appropriate Recall Interval for Periodontal Maintenance: A Systematic Review. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pract. 2015, 15, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| WHO Region | Proportion of Persons with Untreated Dental Decay | Proportion of Persons with Severe Periodontal Disease | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Dentition | Permanent Dentition | ||

| African | 38.6% | 28.5% | 22.8% |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 45.1% | 32.3% | 17.4% |

| European | 39.6% | 33.6% | 17.9% |

| Americas | 43.2% | 28.2% | 18.9% |

| South-East Asia | 43.8% | 28.7% | 20.8% |

| Western Pacific | 46.2% | 25.4% | 16.3% |

| Global | 42.7% | 28.7% | 18.8% |

| Author/(Year)/ Country | Study Objectives | Method | Mode of Analysis | Results/Conclusions/Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fee et al. [24] (2020)/UK | To determine the optimal recall interval for oral health in a primary care setting | A systematic review based on electronic searches of the following databases.

| This Cochrane review adopted the below strategies in the analysis.

| Results: The search strategy yielded 2289 references, which was brought down to 1423 after removing duplicates. Four studies were selected for full-text reading and of these only two studies met the inclusion criteria for final review. One study conducted in Norway compared 12-month versus 24-month recall intervals by measuring outcomes at 24 months. The other was conducted in the UK, which compared the effects of 6-month, 24-month and risk-based recall intervals by measuring outcomes at 48 months. The number of studies were not sufficient to conduct meta-analysis, publication bias or sensitivity analysis. Conclusions:

|

| Lamont et al. [25] (2018)/UK | To ascertain the beneficial and harmful effects of:

| This Cochrane systematic review was based on searching the following databases:

Primary outcome was periodontal disease ascertained by gingival indices, whereas secondary outcomes included clinical status, patient-centred and economic cost factors. | The following strategies were employed in the analysis:

| Results: The search strategy retrieved 1002 records after removing duplicates. Abstract and title sifting resulted in only one study being retained, while another study from the previous review was included, making it two studies for the final review. Both studies were based in the UK and included 1711 participants who did not have severe periodontitis attending regularly at general dental practices. These two studies provided data for two of the three comparisons intended—none of the studies had data for the third comparison. The outcomes were measured at 24 months in one study and at 36 months in the other. Conclusions:

|

| Farooqi et al. [26] (2015)/USA | To evaluate the evidence regarding the most appropriate time interval for periodontal maintenance (PM), for patients previously treated for chronic periodontal disease | A search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE and PubMed up to April 2014. Inclusion criteria:

| The strength of studies was evaluated and the findings were synthesized as per the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) guidelines that comprised 12 questions. | Results: The search strategy yielded 1095 articles, of which 8 cohort studies were included in the final review. There were no RCTs among them. The effect of compliance level with the suggested PM regimen, varying in the range of 3–6 months, on tooth retention as the outcome was evaluated by the eight studies included. While a considerable heterogeneity among the studies existed, one study was rated as excellent, three as good and two each as fair and poor, according to the quality and strength of the studies rated using the CASP criteria. The main findings of the review were as follows:

While highlighting that the review was limited by the non-availability of published RCTs on this subject, studies directly comparing different recall intervals and their effect on periodontal parameters or tooth loss, information on non-compliers (barring one study) and uniform study designs and recall regimens, the authors concluded that:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amarasena, N.; Luzzi, L.; Brennan, D. Effect of Different Frequencies of Dental Visits on Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196858

Amarasena N, Luzzi L, Brennan D. Effect of Different Frequencies of Dental Visits on Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(19):6858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196858

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmarasena, Najith, Liana Luzzi, and David Brennan. 2023. "Effect of Different Frequencies of Dental Visits on Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 19: 6858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196858

APA StyleAmarasena, N., Luzzi, L., & Brennan, D. (2023). Effect of Different Frequencies of Dental Visits on Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(19), 6858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196858