Peer Crowds and Tobacco Product Use in Hawai‘i: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Methods

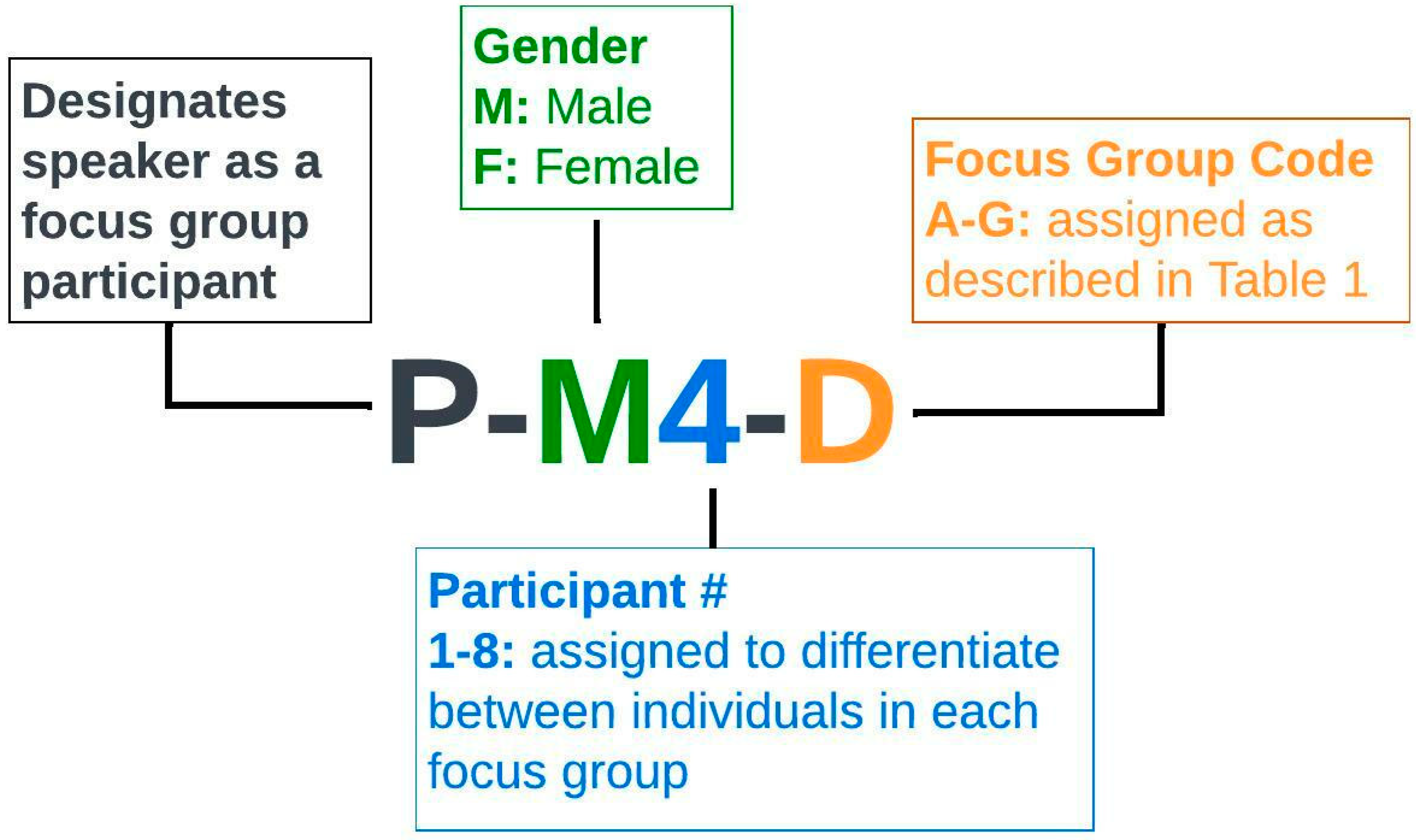

2.1. Recruitment and Participants

2.2. Focus Groups

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Synthesis of Peer Crowd Names Categories

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Peer Group Categories

3.2.1. Regular

3.2.2. Academic

“School People”

P-M3-A: One group I want to add to this is people who go to school because you have people that didn’t go to school and enjoy life. I’m on Instagram and I’ll see someone in Spain again, while I’m getting ready for work. Going to work and school, depending on what you do with your life, that time is one of the hardest things you could go through because you spend 40 hours with school itself, studying, taking tests, and work.

Moderator: Is there a name for this kind of people?

P-M1-A: School people.

3.2.3. Alternative

P-M1-B: I know for sure in Kalihi we have a huge population of those who like to hang out with those who are in a different sexual orientation. I know that for sure, like LGTBQ, male-to-male, female-to-female. They like to hang out.

Moderator: And there’s a subculture surrounding that?...What are their defining characteristics in terms of behavior?

P-F5-B: Just thinking about it, they’re into drag culture. They like to hang out at Scarlet [a drag nightclub] in downtown [Honolulu], go to the gay pride events, like the gay parade. They also have gay families. Some of them share a last name that’s not their official last name.

P-M1-B: I have family relatives like that, who are LGBTQ, and they smoke more, they do illegal drugs. They’re open because they’re always being judged, so they do stupid stuff.

P-F5-B: So you’re saying gay people are more prone to use substances?

P-M1-B: From my experience…Some of them are, right out of high school.

3.2.4. Athletes

3.2.5. Geek

3.2.6. High Risk

3.2.7. Popular

Moderator: So vape is very common among hypebeasts? Or sneaker heads? Or ABGs?

P-M1-C: Yeah, I think all the subgroups that we’ve told you guys about right now, do vape a lot, so vaping is a really big thing right now.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Drug Prevention and Education

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hawai‘i Tumor Registry. Hawai‘i Cancer at a Glance 2014–2018; Hawai‘i Tumor Registry: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hawaii State Department of Health. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Current Cigarette Smoker (Yes), Age-Adjusted. 2020. Available online: https://hhdw.org/report/query/result/brfss/SmokeCurrent/SmokeCurrentAA11_.html (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Hawaii State Department of Health. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Current Cigarette Smoker (Yes), by Age Group and Race. 2020. Available online: https://hhdw.org/report/query/result/brfss/SmokeCurrent/SmokeCurrentCrude11_.html (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Hawaii State Department of Health. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, E-cigarettes Ever Use (Yes), Native Hawaiian & Other Pacific Islander, Ages 18–34. 2020. Available online: https://hhdw.org/report/query/result/brfss/SmokeECigsEver/SmokeECigsEverCrude11_.html (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Hawaii State Department of Health. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, E-cigarettes Ever Use (Yes), Ages 18–34, Grouped by Census Race. 2020. Available online: https://hhdw.org/report/query/result/brfss/SmokeECigsEver/SmokeECigsEverCrude11_.html (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Thompson, A.B.; Mowery, P.D.; Tebes, J.K.; McKee, S.A. Time trends in smoking onset by sex and race/ethnicity among adolescents and young adults: Findings From the 2006–2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lienemann, B.A.; Rose, S.W.; Unger, J.B.; Meissner, H.I.; Byron, M.J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Huang, L.-L.; Cruz, T.B. Tobacco advertisement liking, vulnerability factors, and tobacco use among young adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, P.M.; Neilands, T.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Kaplan, C.P. Psychographic segments based on attitudes about smoking and lifestyle among Vietnamese-American adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, M.B.; Walker, M.W.; Alexander, T.N.; Jordan, J.W.; Wagner, D.E. Why peer crowds matter: Incorporating youth subcultures and values in health education campaigns. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev. Perspect. 2007, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brechwald, W.A.; Prinstein, M.J. Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moran, M.B.; Sussman, S. Social identity and antismoking campaigns: How who teenagers are affects what they do and what we can do about it. In Talking Tobacco: Interpersonal, Organizational, and Mediated Messages; Esrock, S.L., Walker, K.L., Hart, J.L., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, S.; Pokhrel, P.; Ashmore, R.D.; Brown, B.B. Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: A review of the literature. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 1602–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moran, M.B.; Villanti, A.C.; Johnson, A.; Rath, J. Patterns of alcohol, tobacco, and substance use among young adult peer crowds. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, e185–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T.W.; Ritt-Olson, A.; Stacy, A.; Unger, J.B.; Okamoto, J.; Sussman, S. Peer acceleration: Effects of a social network tailored substance abuse prevention program among high-risk adolescents. Addiction 2007, 102, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.W.; Stalgaitis, C.A.; Charles, J.; Madden, P.A.; Radhakrishnan, A.G.; Saggese, D. Peer crowd identification and adolescent health behaviors: Results from a statewide representative study. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Pokhrel, P.; Sussman, S. The intersection of social networks and individual identity in adolescent problem behavior: Pathways and ethnic differences. Self Identity 2022, 21, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Galimov, A.; Meza, L.; Huh, J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Pokhrel, P. Peer crowd identification of young and early middle adulthood customers at vape shops. J. Drug. Educ. 2021, 50, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, P.; Fagan, P.; Herzog, T.A.; Laestadius, L.; Buente, W.; Kawamoto, C.T.; Lee, H.-R.; Unger, J.B. Social media e-cigarette exposure and e-cigarette expectancies and use among young adults. Addict. Behav. 2018, 78, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, D. The cycle of popularity: Interpersonal relations among female adolescents. Sociol. Educ. 1985, 58, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher, J.B.; Baizerman, S.; Michelman, J. Adolescent dress. Part II: A qualitative study of suburban high school students. Adolescence 1991, 26, 679–686. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham, S.; Ogbu, J.U. Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of ‘acting white’”. Urban Rev. 1986, 18, 176–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.B.; Sussman, S. Changing attitudes toward smoking and smoking susceptibility through peer crowd targeting: More evidence from a controlled study. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawaii State Department of Health. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Current Cigarette Smoker (Y/N) Filter Grouped by Year, DOH Race Ethnicity. 2020. Available online: https://hhdw.org/report/query/result/brfss/DOHRaceNewCat/DOHRaceNewCatCrude11_.html (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Tang, K.C.; Davis, A. Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Fam. Pract. 1995, 12, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR Inernational Pty Ltd. Nvivo, Version 12; QSR International: Burlington, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Holmes, L.M.; Kim, M.; Ling, P.M. Using peer crowd affiliation to address dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among San Francisco Bay Area young adults: A cross sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Dictionary. Chronic. Available online: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=chronic (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Jankowski, M.; Wrześniewska-Wal, I.; Ostrowska, A.; Lusawa, A.; Wierzba, W.; Pinkas, J. Perception of harmfulness of various tobacco products and e-cigarettes in Poland: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soule, E.K.; Rossheim, M.E.; Cavazos, T.C.; Bode, K.; Desrosiers, A.C. Cigarette, waterpipe, and electronic cigarette use among college fraternity and sorority members and athletes in the United States. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, P.; Little, M.A.; Herzog, T.A. Current methods in health behavior research among U.S. community college students: A review of the literature. Eval. Health Prof. 2014, 37, 178–202. [Google Scholar]

| Focus Group Code Letter | Number of Participants | Participants’ Gender | Participants’ Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 3 males, 3 females | 4 Filipino, 1 Hispanic, 1 White |

| B | 5 | 1 male, 4 females | 4 Filipino, 1 White |

| C | 4 | 2 males, 2 females | 1 Filipino, 1 Korean, 1 Japanese, 1 White |

| D | 6 | 2 males, 4 females | 4 Native Hawaiian, 1 Filipino, 1 Japanese |

| E | 8 | 4 males, 4 females | All Native Hawaiian |

| F | 8 | 4 males, 4 females | 7 Native Hawaiian, 1 Hispanic |

| G | 5 | 2 males, 3 females | 3 Native Hawaiian, 1 Tahitian, 1 White |

| Academic | Alternative | Athletic | Geek | High Risk | Popular |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Preppy” “Scholars” “School people” | “Woke” “Artsy people” “Environmentalist” “Goth” “Hippie” “Hipster” “LGBTQ+” “Māhū” 1 “Mālama ‘Āina” 2 “Photographer” “Tree hugger” “Vegan” | “Athlete” “Football boy” “Gym rat” “Hiker” “Sports enthusiast” “Surfer” “Spungah” 3 | “Anime kid” “Koreaboo” 4 “Kpop people” 5 “Otaku” 6 “Weaboo” 7 “Gamer” “Nerd” | “Jerks” “Douchebag” “Chronic” “Banger” “Frattie” “Ghetto Kids” “Stoner”/“Kanak Stoner” 8 “Loner” “Moke bangah” 9 “Narc” “Party animal” “Ratchet” 10 “Raver” “Smoker” “Union boy” 11 “Wannabe” “Weirdo” “Emo” 12 “Ho” “THOT” 13 | “Beach bum” “ABG” 14 “Basic bitch” 15 “Beauty guru” “Car people/Car cruisers/Car crew” “Dancer” “Foodie” “Fuck boy” 16 “Fuck girl” 16 “Hypebeast” 17 “IG hoes/model” 18 “Import model” 19 “Jock” “Pretty boy” “Rich kid” “Sneaker head” “Tita” 20 |

| Alternative | |

|---|---|

| Peer Crowds | Excerpts |

| Woke | P-F5-B: Is there a group name for these people that, as you mentioned, like to be involved in the women marches and activism in general? P-F3-B: I think it’s woke. I see it on Instagram. P-F5-B: There’s a hashtag that’s like, “#woke”, like you’re trying to be part of democracy and about civil engagements. Like, you’re awake. P-F3-B: You’re not ignorant to things. |

| Goths | P-M8-F: Did we get the Goths? Moderator: Tell us more about Goths. P-M8-F: More than likely, they wear dark shades of makeup and piercings all over their body. Listen to rock all the time. Worship Satan maybe. They are just different. |

| Mālama ‘Āina | P-F4-D: The Mālama ‘Āina group, a lot of them, I feel, they … just like to go outside and cut down trees or whatever, but I feel like a lot of the people who are in the Mālama ‘Āina field do it for their culture, like the Hawaiian culture, and their standards are very cultural-based. |

| Athlete | |

| Peer Crowds | Excerpts |

| Gym Bros/Rats | Moderator: How would you define a gym rat? P-F6-A: Goes to the gym every day, works out at the gym every day. P-M3-A: They don’t have to work, go to gym. P-F5-A: Carry around a protein shake every day. P-M3-A: Meal prep. P-M4-A: Protein, chicken, eggs. P-F5-A: Broccoli. Moderator: Do they vape? P-M2-A: A lot of them … Hawai‘i is like, “I’ll go to the gym but we’re going to have a beer later because we can burn it off tomorrow at the gym”. But smoking-wise, like, “Oh, I have to get my cardio up, but I’m going to vape right after”. I’ve seen that happen so many times. Moderator: So you think gym rats more often would be vaping rather than smoking. P-M2-A: More vaping, yeah. P-F1-A: Vaping is too permanent of a thing. P-M2-A: Yeah, because gym rats are more focused on muscle building rather than cardio, but they do vape. Like, I passed this new gym in Ala Moana, some Planet Fitness, and I saw a guy adding stuff to his vape inside the gym and he’s vaping at the same time, like I think he’s contradicting everything. I just saw that last night, so I was just tripping out. |

| Spungahs? (pronounced SPUN-jahz) | P-F5-D: Spungahs. P-M2-D: It’s in tandem with surfers. P-F5-D: It’s more like local people, though. Surfers can be like foreign people that come here to surf, so down here there’s spungahs. Local people like ourselves that go to the beach a lot and smoke weed. My friends from high school were top spungahs. They would smoke weed, drink, and just have a good time. |

| Geek | |

| Peer Crowds | Excerpts |

| Anime Kid | Moderator: Could you help me visualize an Anime kid? P-F4-F: They have crazy hair colors. I don’t know how to explain them. P-M8-F: Kids that wear stuff that people wouldn’t call normal. They wear things that come out of animated cartoons, like a Pikachu hat, or a Pikachu one-piece. P-M1-F: The cough masks. P-M8-F: They paint their faces. P-M1-F: They cosplay. The Japanese thing, costume play. P-M8-F: But usually they’re not Japanese. P-M1-F: Sometimes they wear claws, mittens, whiskers. |

| K-pop People | P-F2-F: [K-pop people] have a bunch of things: They have a lot of fan groups, so there’s apps that you can have for that one group that you really like. There’s a whole community, and they set up events, and there’s fans that fly out and meet. |

| Gamers | P-M2-D: The first group that comes up is gamers. I have to say it because I play games every day. I wouldn’t say that I embody that group, or present it all the time, but I play games every day. Moderator: Is there a behavior in addition to gaming that applies to gamers? P-M6-D: I play games. A lot of them smoke, a lot of my friends who I’ve connected with online, they all tend to smoke. Moderator: These are all gamers? P-M6-D: Yeah. P-F5-D: Smoke cigarettes? P-M6-D: I know a lot of gamers, and there’s definitely those who smoke to get high and play games at the same time. I know those who take breaks after intermissions of MPG, they’ll be like, “I’m going to smoke real quick, be right back”. P-M2-D: There’s a lot of YouTubers or Twitch-streamers, people that stream themselves playing games. Twitch is a website where you can stream yourself playing games and make money. In that, you can see some people smoke while they play, they swear, whatever. They drink, some people make a game out of it, and they’ll drink while playing. Moderator: Do they vape as well? P-M2-D: I would say more recently, I’ve seen a lot more electronic [cigarettes]. P-M6-D: Because they can do it inside their room or certain places. Moderator: What about alcohol use among gamers? Is it common? P-M2-D: I can’t say for sure. I don’t want to be drunk and play games. P-M6-D: I love it! I can just talk to people when I’m, you know, and get competitive. But I know there’s certain groups that all drink and play games, and they all just have a good time. Moderator: These are gamers too? P-M6-D: Yeah. |

| Koreaboo | Moderator: So these groups that are obsessed with Japanese and Korean cultures, is smoking or vaping more prevalent in the groups or no? P-F5-A: A lot of them don’t, only because it’s like, “Oh, we’re introverted, we just want to stay inside and stay up until 2 in the morning to watch our groups perform” and stuff like that, from what I’ve seen. But I do know that there’s a lot of them that were past smokers, and they’re like, “Oh, this is my new outlet now”. So I’ve had maybe 4 or 5 friends like that. |

| High Risk | |

| Peer Crowds | Excerpts |

| Chronics | Moderator: Could you describe chronics? P-M2-E: You can just tell, you have to be around to just know. P-M3-E: Some chronics are crazy. They think people are talking to them, or they tweak out and think someone’s trying to rob them. P-M4-E: I used to work with this guy, you wouldn’t tell, but when he would work, he would clean everything, like full on. I used to work at a kitchen; pull out all the refrigerators, scrub the floor, under the refrigerators, clean out the refrigerators, like just yeah. P-M2-E: Chronics our age, they wouldn’t be here, in school. P-M3-E: They’d probably be chilling on the block somewhere. |

| Stoners and Ghetto Kids | P-F4-F: What I see are… The ghetto kids in Wai‘anae, like literally ghetto. Some of them don’t brush their teeth, don’t wear slippers … Then there’re the stonies, and they just chill, mind their own business, take care of themselves, smoke weed. Moderator: The names that you’ve mentioned, is tobacco use, e-cig use, common among some more than others? P-M8-F: More than likely those, yeah. Moderator: Who’s it common among? P-F4-F: The stonies and the ghetto kids. |

| Moke Bangahz | P-M2-E: Get the moke bangahz, da kine bonfire, but every day bonfire, party, fish, dive, scrap anybody just for fun, drink beer, you know. Swear every f-word, and it’s not even negative, that’s just part of their vocabulary. Moderator: These are the moke bangahz? P-M2-E: Yeah, and if you want to get into what they wear … Moderator: Go ahead. P-M2-E: Okay, there’s levels to this moke bangahz, there’s the moke braddahs that wear slippers, surf shorts, t-shirt … And they get the one that dress to kill, moke bangahz, who get the [gold] chain, the nice shirt, the jeans. I’ll bark at them, but they’ll bark back. |

| Party Animals | P-F8-E: Party animals party a lot. P-M2-E: They start drinking, they want to smoke. P-M3-E: We got those drinking, smoking. P-F8-E: Cross-faded. P-M3-E: They only smoke cigarette when they drink, but they don’t want to buy their own pack. |

| Ravers | P-M1-C: Ecstasy for the ravers. P-M3-C: For ravers, ecstasy is one of the top ones. Moderator: Is vaping culture big among ravers too? P-M1-C: Absolutely. Moderator: And they vape stuff other than nicotine? Do you know? P-F4-C: I think it’s more common, but I’ve heard of some people who use it for marijuana stuff. I forgot what it’s called. P-M3-C: Dab? P-F4-C: Yeah. P-M3-C: They have the THC dab. |

| Popular | |

| Peer Crowds | Excerpts |

| ABGs | P-F4-C: Not to offend anybody, but I think ABGs are considered more attractive? Or the popular … Yeah. Moderator: Can you describe ABGs a bit more? P-F2-C: I know some people. Most of them are from the west side, a group of girls, and they’re really into eyelashes, makeup, like going all out … Spending two hours on their makeup. When they go out, they wear bling everything. They wear boots covered over their knees. You would think you wouldn’t dress like that in Hawai‘i. I do not know what you would call them … Boujee? |

| Hypebeasts | P-F4-C: Hypebeasts. P-M1-C: Hypebeasts are more like clothing too. Street style. P-F4-C: Guys who are really into hats and shoes, but it’s more like a specific type of clothing that they’re into. P-F2-C: Like Supreme. |

| Car People | P-F1-A: The car people, if you look at them, you know they’re a car or motorcycle person. Moderator: Why? P-F1-A and P-F5-A: The way they dress. Moderator: How do they dress? P-F1-A: Expensive wear. P-F5-A: They wear a lot of street wear. My boyfriend is part of a car crew and his group, all of them are sneakerhead, like that’s their thing, and if they do vape, they like to do it out in open parking lots. They never do it in their car because they don’t want their car to smell like the vape. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tabangcura, K.R.; Taketa, R.; Kawamoto, C.T.; Amin, S.; Sussman, S.; Okamoto, S.K.; Pokhrel, P. Peer Crowds and Tobacco Product Use in Hawai‘i: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021029

Tabangcura KR, Taketa R, Kawamoto CT, Amin S, Sussman S, Okamoto SK, Pokhrel P. Peer Crowds and Tobacco Product Use in Hawai‘i: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021029

Chicago/Turabian StyleTabangcura, Kayzel R., Rachel Taketa, Crissy T. Kawamoto, Samia Amin, Steve Sussman, Scott K. Okamoto, and Pallav Pokhrel. 2023. "Peer Crowds and Tobacco Product Use in Hawai‘i: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021029

APA StyleTabangcura, K. R., Taketa, R., Kawamoto, C. T., Amin, S., Sussman, S., Okamoto, S. K., & Pokhrel, P. (2023). Peer Crowds and Tobacco Product Use in Hawai‘i: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021029