1. Introduction

Free unconstrained thoughts, important for the enhancement of knowledge and the verve of a self-ruled society, emerge from the places known as universities [

1]. The universities provide knowledge promoters with academic freedom, by supporting their expression of ideas, indifferently, whether they are controversial, fictitious, uncommon, or may attract retaliation [

2]. This very aspect, that makes our higher education system irreplaceable, attracts numerous challenges from various routes. Meeting global standards, unsettling technologies, funding concerns, knowledge modification, areas of obsolescence, and marketization create enormous pressure on the institutions to survive, on faculty to deliver and on scholars to cope [

2]. Such internal-external stressors, themselves sometimes categorized as bullying [

3] make it difficult for the universities to survive in the resource-constricting environment and pose challenges for the faculty with their constant changing roles [

4].

Workplace bullying, the obstruction to decent work [

5], has been documented as a global concern [

6]. Elimination of violence and harassment from workplaces marked as a significant goal with the adoption of Convention 190 by the International Labour Organization in 2019 [

7]. The progress of Asian nations towards the achievement of sustainability, the blueprint of United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals [

8], can be mapped with the achievement of peace and prosperity throughout the region and making the functional institutions stronger [

9].

Bullying in academe is perceived as wide-spread with universities being amongst the worst workplaces [

2,

10]. Further, examining the impact of bullying in academia, it is affirmative that losses occurs at a number of levels: loss for the one who is victim to bullying (health and wellbeing); the cost to the department (loss of an employee, upset schedules); damage for students (reduced teaching quality and unsatisfying mentoring); loss to institutions (of time, money and resources); and failure for society (undermined intellect and freedom) [

2,

11,

12].

Research on workplace bullying in the education sector primarily originates from western countries such as USA [

13], Canada [

13], Europe [

14], Australia [

15] and New Zealand [

16]. Further, increasing research from the other parts of the world such as the Middle East [

17], Africa [

18], India [

19] and Pakistan [

12] can also be witnessed. Given the significant role of the faculty in academia, the focus of research has been largely on experiences of faculty as targets, witnesses, and actors in workplace bullying [

2].

As the educational setting involves faculty, who are mentoring students and impacting their lives, the cost of work stress can be upsetting [

20]. The earlier studies have reported that employees who are young, novice, less experienced, relatively have lower level of education, junior faculty and faculty-in-training are more vulnerable to bullying in higher education institutions [

2,

4,

11,

12].

Over three decades the research has progressed to study antecedents and outcomes of bullying; however, research relating to coping has emerged noticeably only in recent years [

21]. Coping has been defined as the efforts made to tolerate, master or reduce the effects of conflicts [

22]. Raising one’s ‘voice’, complaining, support seeking, patience, aggression, problem avoidance, withdrawal from work, intent to leave, quitting the organization, social isolation, etc., are various coping strategies used by the targets to workplace bullying [

21].

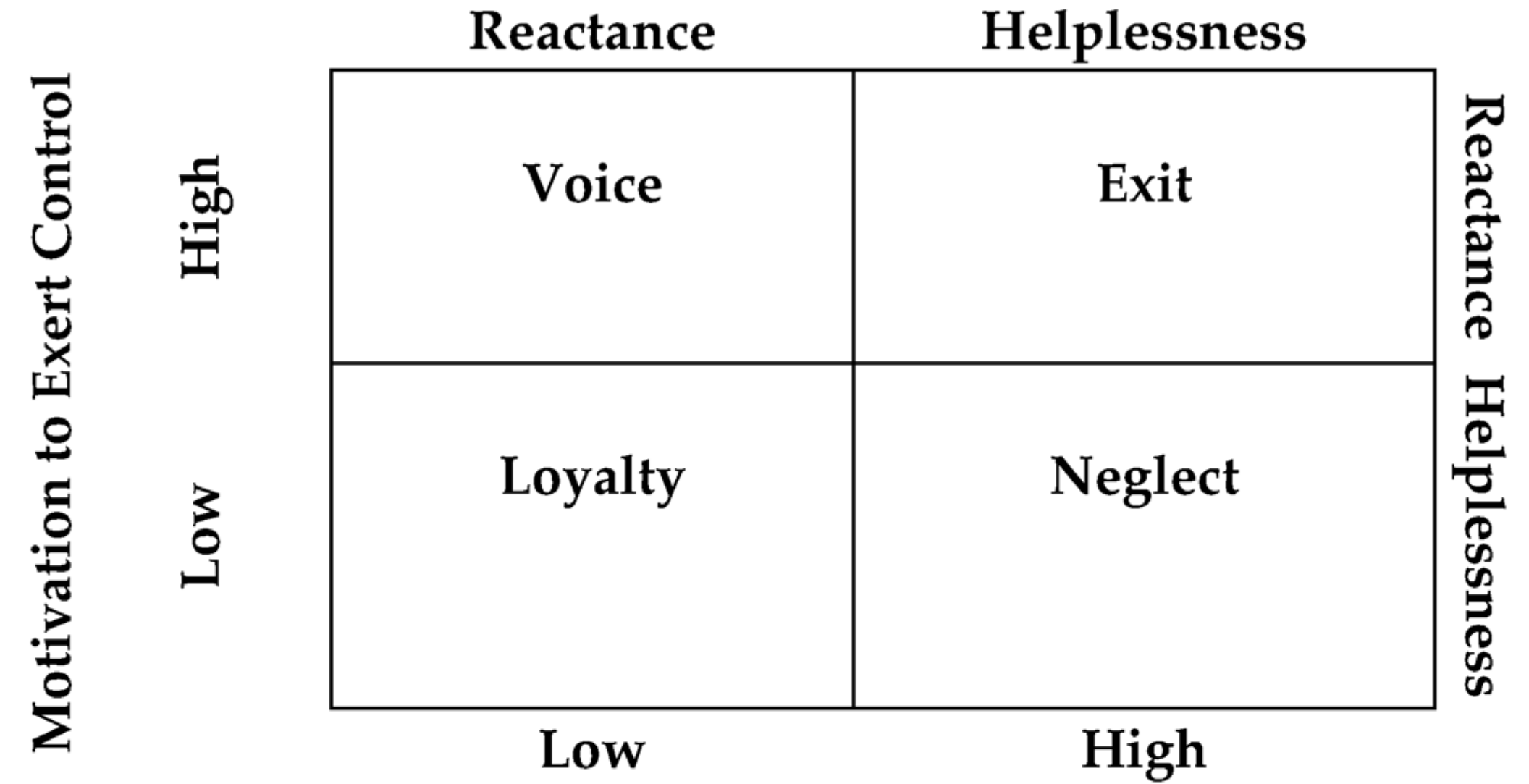

Of the various coping responses this study employs the framework of exit, voice, loyalty and neglect (EVLN) outcomes, which has been widely accepted [

21]. The framework of EVLN to study employee responses in adverse situations was first proposed by Hirschman [

23] as the exit-voice-loyalty model of dissatisfaction and later was expanded by others [

24,

25] introducing neglect as the fourth response.

Workplace bullying, embraced as systematic flaws in the organizations [

26] if there are permissive environments to such behaviors, imposes severe threats to their functioning [

27]. High tolerance has been described as allowing certain behaviours even though they are considered illegitimate [

28]. The question of high organizational tolerance to such negative acts has been raised time to time, yet remains unanswered operationally to date [

28].

In academe particularly, the state of job insecurity and dependence on the senior permanent faculty put junior faculty at higher risk and decrease their tendency to defend themselves (‘voice’) [

29]. Talking to friends and family [

30,

31,

32] and seeking support from colleagues [

33,

34] have been frequent responses to the negative experience of workplace bullying. However, friends and family could only provide emotional support, not being from the university [

35], and support from colleagues came with the expectation to involve in direct action [

34]; informing the significant people in the university has the utmost opportunity of bringing required change [

2,

36], but given the literature, unfortunately, involvement in the formal complaints system is one of the least chosen responses to workplace bullying [

31,

33].

Though the research over the decades has supported better understanding of coping responses to workplace bullying, several research gaps can be identified that have been neglected. First, substantial research has focused and amassed evidence based on the resource-depletion and social-relational perspective [

37,

38,

39]. Other theoretical standpoints such as social-influence, self-regulation, routine-activities theory or the integration of different theoretical models seem deserted. Secondly, most of the literature focuses on cross-sectional research design. More prospective and robust designs can be experimented with [

38]. Third, very few studies can be identified signifying the importance of organizational moderators of bullying [

40]. This aspect is as yet at an emerging stage of the research agenda and has larger scope [

38]. Lastly, coping perspectives in the wider education sector and understanding of the organizational perspectives are yet underexplored.

Therefore, this study aims to fill the listed gaps by employing an integrated theoretical model of reactance and learned helplessness theory with the perceived organizational tolerance as the moderator between workplace bullying and the coping responses, focusing only on targets of workplace bullying. The paper follows the course of providing a theoretical background and hypotheses development, research methodology depicting results, followed by discussion and implications, understanding limitation, and discovering future research directions along with conclusions.

5. Discussion

As workplace bullying had been labelled as ‘rife’ in higher education [

2], the study mainly focused on the junior faculty, to understand how the faculty at lower levels find themselves intimidated and their positions at risk, since supervisor bullying is common and widely practiced [

4,

11,

12]. The junior faculty understudy in phase 1 of our survey can be largely seen at risk of being bullied or being occasionally bullied.

When these targets to workplace bullying were further studied in the second phase, the results reflected a significant relationship between workplace bullying and neglect as a coping response (

Table 5). Workplace Bullying showed a positive relationship with Exit, and a negative relationship with Voice as expected [

49] but the relationship was insignificant. However, it was surprising to see a positive relationship between Workplace Bullying and Loyalty. A plausible explanation to this positive relation can be attributed to the theoretical underpinning [

44], where targets may find supervisor mistreatment as acceptable [

89], tending to perceive themselves less exposed to uncontrollable situations that way and therefore waiting for the time to get things right.

Further, the study by Leach [

63], states that the employees who were the less experienced teachers, were the ones who showed most loyalty. Since this study deals with the junior faculty, it can be comprehended that the faculty tries to accommodate to the organizational setting and therefore waits for the situation to get better with time. Further, Wu and Wu [

104] stated in their study that even when the employees were ignored by HR, they remained loyal to the organization hoping that with time the situation would get resolved. Workplace Bullying and Neglect showed the most significant relationship. It can thus be interpreted that of all the coping responses of EVLN, the assistant professors prefer to adopt neglect behaviors as a shield. Keashly [

2], Karatuna [

105] and Rai and Agarwal [

106] also noted in their studies that when it is difficult for the faculty to leave a bullying situation through internal transfer or to move to a different academe environment altogether or targets have no energy to deal with the situation, the faculty withdraws itself from work in ways that are not productive.

Further when perceived organizational tolerance was allowed to moderate the relationship;, there was an increase in raising of voice when the institution was perceived to have low tolerance for bullying. This signifies the importance of low perceived tolerance, as it induces employees to practise constructive coping strategies [

107]. With the low POT, targets tend to get motivated to take control of the situation and therefore get themselves out of the state of helplessness, as stated in the theory [

44].

At the same time, it can be witnessed that the faculty who perceived low organizational tolerance also tended to increase their exit and neglect behavior. In the literature, supporting evidence can be seen that with the escalation of workplace bullying, exit and neglect behaviors increase. It is interesting to note that it is more prevalent amongst the employees who perceive that the organization is less tolerant of bullying. This can be understood from the state of learned helplessness [

44], where despite the chances to improve the situation, targets have learned that the situation cannot be improved and therefore practice exit-neglect responses. Training to employees where they can get themselves out of uncontrollable situations through plausible solutions can be a possible result oriented strategy to divert the helplessness response of targets to reactance response. Moreover, in a collectivist society like India where there is high preference to belonging to a larger social framework and being rejected or isolated leaves the person rudderless, such coping responses can be comprehended [

34,

108].

POT does not act as a significant moderator between workplace bullying and Loyalty, but it can be seen that when low tolerance to workplace bullying is perceived, loyalty is high. This shows that the targets tend to increase their loyalty and choose to stick to the organization with the hope of the organization addressing the problem [

60].

It was initially expected that low institutional tolerance of bullying would help targets to handle the situation constructively; it is unfortunate to see that low tolerance, while adding to constructive handling, at the same time adds to exit and neglect behaviors as well. These results clearly affirm theoretical propositions [

44], that if the actions are taken on time by the organization, it can manage to keep the targets under the reactance bracket of voice and loyalty; however, once the state of helplessness is assumed, it gets difficult to change the perception.

From the previous studies it can be inferred that even in the organizational cultures where tolerance of bullying is perceived as low, the effective action takes a prolonged period of time and the stretched process of dealing with the extended bullying [

52,

109,

110,

111,

112] forces employees to indulge in behaviors that depict withdrawal. A pre-accepted notion of ‘nothing will be done’ or even if done would make not much difference (leaving them in a ‘status limbo’) in the situation, and rather might bring retaliation, does not allow even the world changers to bring a change in their situation [

2].

Therefore, it is recommended for the organizations and the administrations to build a solid foundation by laying down anti-bullying policies and strong implementation of the same so as to ensure that the lag between where a faculty member wishes to raise a voice and needed support is shortened, thereby avoiding the necessity of choosing to exit or practice neglect. A bullying target being loyal to the organization is in some ways a constructive response for the organization; however, is not really constructive, as, if no action is taken, the employee ultimately loses trust in the organization and resolves to shift towards exit or neglect disappointedly [

21,

105]. The practice of neglect as a coping response not only produces personal or professional cost for the faculty in suffering but at the same time it impacts their ability to engage in mentorship of students, putting their careers, knowledge and course progressions in danger [

2].

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Theoretical Implications

The study employs the integrated model of reactance and learned helplessness [

44] in terms of coping and workplace bullying. It adds to the literature by employing an integrated model of the two theories, as most of the previous coping literature goes with resource-depletion perspective. Further, the study adopts a multi-level research design by conducting the study in two phases, considering only the targets in the second phase, instead of considering all employees as done by previous researchers at large. This brings a new operationalized perspective on target behavior and adds to the literature of distinguishing between bullied and non-bullied behaviors. Further, to the best of authors’ knowledge, this study is first to use perceived organizational tolerance as an operationalized construct in the literature of workplace bullying and higher education. It also adds to the scarce literature of organizational moderators, to which only a few studies have contributed [

40]. In addition, studies in the education sector in Asian countries are scarce and this is an addition to the bullying literature on higher education in Asian nations [

2].

5.1.2. Practical Implications

Understanding the coping responses to negative situations at work can empower organizations to form a plan of action. Since low institutional tolerance of bullying provides courage to employees to raise their voice, it is important to build systems such that the targets of any such act can freely reach out for the solution and help. As clearly indicated in the study by Jain [

109], there is lack of policy initiative in the Indian organizations, and the few initiatives that exist have indicated patchy results with improper implementation. If such destructive coping response to workplace bullying in higher education continues along with the personal and professional cost to the target, students’ learning experience will be negatively impacted, not forgetting the negative impact that the universities and the administration may bear in terms of reputation and resources. Organizations need to resolve to implement solutions where they can keep up the expectation of employees that the circumstances can be controlled by them, as if they enter the phase of helplessness, turning back becomes a major challenge.

5.1.3. Societal Implications

On the whole, addressing workplace bullying and diverting employees towards the constructive practice of raising their voice, is the social responsibility of every individual. This will empower us towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals [

8] targeted to be fulfilled by 2030, particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 4 (Quality and Sustainable Education), SDG 8 (Decent Work), SDG 16 (Strong Institutions). In order to develop a healthy educational system, it is important that participants in this system feel safe and are ready to serve in the best way possible.

5.1.4. Public Health Implications

Workplace bullying negatively impacts the physical and mental health of individuals causing a range of problems such as sadness, anxiety, depression, sleeplessness, decreased physical strength, musculoskeletal disorders and a heightened risk of cardiovascular disease etc. [

7]. Therefore, addressing the issue of workplace bullying becomes necessary, to ensure health, safety and wellbeing of the individuals. Better health and wellbeing will further contribute towards increased productivity and effective work performance amongst the faculty of higher education, thereby creating healthy and safe workplaces.