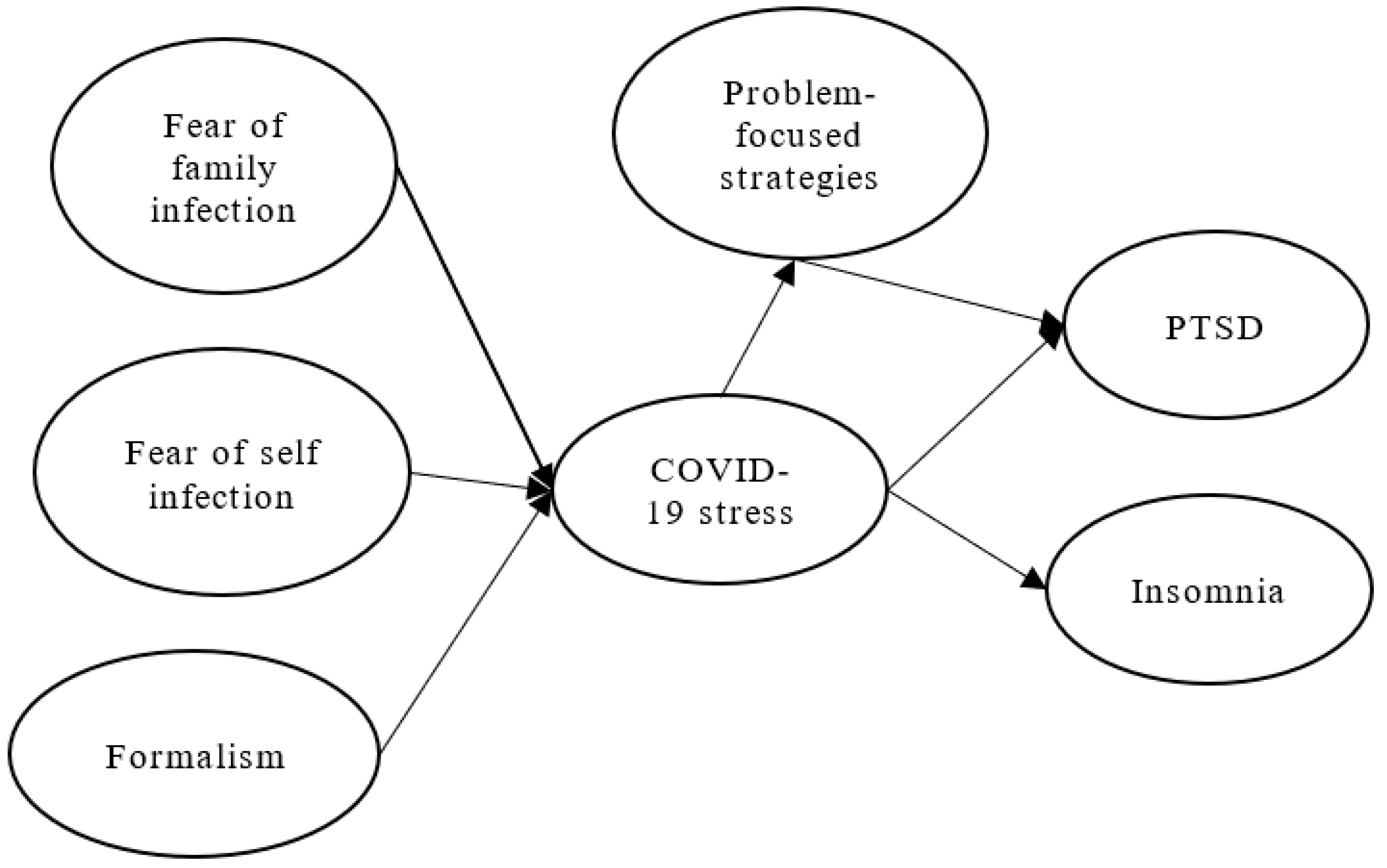

Causal Model Analysis of the Effect of Formalism, Fear of Infection, COVID-19 Stress on Firefighters’ Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome and Insomnia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample, Tools, and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Validity and Reliability Analysis

3.4. Controlling for Common Method Variance (CMV)

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzalez, A.; Rasul, R.; Molina, L.; Schneider, S.; Bevilacqua, K.; Bromet, E.J.; Luft, B.J.; Luft, B.J.; Schwartz, R. Differential effect of Hurricane Sandy exposure on PTSD symptom severity: Comparison of community members and responders. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Peng, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chang, J.; Chan, C.-H.; Yang, D.-Y. The psychological effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on emergency department staff. Emerg. Med. J. 2007, 24, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.; Wu, X.; Lan, X. Rumination mediates the relationships of fear and guilt to posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1704993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xi, Y.; Yu, H.; Yao, Y.; Peng, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and the role of resilience, social support, anxiety and depression after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake: A structural equation model. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 49, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Zhang, E.; Wong, G.T.F.; Hyun, S.; Ham, H.C. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, Y. Psychological distress related to COVID-19—The contribution of continuous traumatic stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Shuwiekh, H.A.M.; Rice, K.G.; Ashby, J.S.; Elwakeel, S.A.; Sous, M.S.F.; Alhuwailah, A.; Baali, S.B.A.; Azdaou, C.; Oliemat, E.M.; et al. Measuring covid-19 as traumatic stress: Initial psychometrics and validation. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 26, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kira, I.A.; Shuwiekh, H.A.M.; Ashby, J.S.; Elwakeel, S.A.; Alhuwailah, A.; Sous, M.S.F.; Baali, S.B.A.; Azdaou, C.; Oliemat, E.M.; Jamil, H.J. The Impact of COVID-19 Traumatic Stressors on Mental Health: Is COVID-19 a New Trauma Type. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, H. Nursing in the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: Protecting, saving, supporting and honouring nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 67, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Mo, P.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, O.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F. Post-discharge surveillance and positive virus detection in two medical staff recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), China, January to February 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, M.; Ebrahimi, B.; Nemati, F. Assessment of Iranian nurses’ knowledge and anxiety toward COVID-19 during the current outbreak in Iran. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 15, e102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Hayter, M.; Lee, A.J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, S.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cao, C.; Gong, W.; Zhang, Y. Positive spiritual climate supports transformational leadership as means to reduce nursing burnout and intent to leave. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kameg, B.N. Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing Leadership during Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 28, 507–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerckhove, M.; Wang, Y.L. Emotion, emotion regulation and sleep: An intimate relationship. AIMS Neurosci. 2018, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, C.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Lombardo, C.; Riemann, D. Sleep and emotions: A focus on insomnia. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Kirov, R.; Kalak, N.; Gerber, M.; Puhse, U.; Lemola, S.; Correll, C.U.; Cortese, S.; Meyer, T.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Perfectionism related to self-reported insomnia severity, but not when controlled for stress and emotion regulation. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baglioni, C.; Nanovska, S.; Regen, W.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Feige, B.; Nissen, C.; Reynolds, C.F.; Riemann, D. Sleep and mental disorders: A meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 969–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertenstein, E.; Feige, B.; Gmeiner, T.; Kienzler, C.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Johann, A.; Jansson-Frojmark, M.; Palagini, L.; Rucker, G.; Riemann, D.; et al. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 43, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, A.J. Assessment of insomnia. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 6, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altena, E.; Baglioni, C.; Espie, C.A.; Ellis, J.; Gavriloff, D.; Holzinger, B.; Schlarb, A.; Frase, L.; Jernelöv, S.; Riemann, D. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publising: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zitting, K.-M.; Lammers-van der Holst, H.M.; Yuan, R.K.; Wang, W.; Quan, S.F.; Duffy, J.F. Google Trends reveal increases in internet searches for insomnia during the COVID19 global pandemic. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Casement, M.D.; Kalmbach, D.A.; Castelan, A.C.; Drake, C.L. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia promotes later health resilience during the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham, M.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Kolerman, R.; Mijiritsky, O.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Mijiritsky, E. COVID-19 Factors and Psychological Factors Associated with Elevated Psychological Distress among Dentists and Dental Hygienists in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heymann, D.L. Ebola: Transforming fear into appropriate action. Lancet 2017, 390, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vergara-Buenaventura, A.; Chavez-Tuñon, M.; Castro-Ruiz, C. The Mental Health Consequences of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in Dentistry. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, e31–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perogamvros, L.; Castelnovo, A.; Samson, D.; Dang-Vu, T.T. Failure of fear extinction in insomnia: An evolutionary perspective. Sleep Med. Rev. 2020, 51, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, J.; Ursano, R.J.; Morganstein, J.C.; Kurosawa, M.; Benedek, D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (covid-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.C.; Park, Y.C. Mental health care measures in response to the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Korea. Psych. Investig. 2020, 17, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A.J.; Pantaleón, Y.; Dios, I.; Falla, D. Fear of COVID-19, Stress, and Anxiety in University Undergraduate Students: A Predictive Model for Depression. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 591797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.Y. An outbreak of fear, rumours and stigma. Intervention 2015, 13, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsang, S.; Avery, A.R.; Duncan, G.E. Fear and depression linked to COVID-19 exposure A study of adult twins during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 296, 113699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, O.C.; Amadi, C.O.; Nnaji, S.E. Prebendalism And Budget Authorization in The Nigerian Legislature. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.Y.; So, W.Y. Inevitability of Errors, Justifiability of Hidden Rules: Behavior of Performance Appraisal under Institutional Constraints. J. Civ. Serv. 2017, 9, 79–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, F.W. An ecological approach: The ‘Sala’ Model. In Papers in Comparative Administration; Heady, F., Stokes, S., Eds.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1962; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, R. Mechanistic and organic models of public administration in developing countries. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G.M. The Management of Innovation; Tavistock: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, G.; Joiner, C. Perceptions of the Vietnamese public administration system. Adm. Sci. Q. 1964, 8, 443–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Schuch, J.B.; Sordi, A.O.; Kessler, F.H.P. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porcelli, P. Fear, anxiety, and health-related consequences after the COVID-19 epidemic. Clin. Neuropsychiatry J. Treat. Eval. 2020, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, K.; Bhullar, N.; Jackson, D. Life in the pandemic: Social isolation and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2756–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rogers, J.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.; Lewis, G.; David, A. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. LANCET Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandifar, A.; Badrfam, R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demertzis, N.; Eyerman, R. Covid-19 as cultural trauma. Am. J. Cult. Sociol. 2020, 8, 428–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asim, M.; van Teijlingen, E.; Sathian, B. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the risk of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A mental health concern in Nepal. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2020, 10, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Sun, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for acute posttraumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, F.; Wei, C.; Jia, Y.; Shang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Tambelli, R.; Casagrande, M. COVID-19 pandemic in the italian population: Validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaka, A.; E Shamloo, S.; Fiorente, P.; Tafuri, A. COVID-19 pandemic as a watershed moment: A call for systematic psychological health care for frontline medical staff. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, J.; Ma, X.; et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wang, F. Association between perceived stress and depression among medical students during the outbreak of COVID-19: The mediating role of insomnia. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azim, S.R.; Baig, M. Frequency and perceived causes of depression, anxiety and stress among medical students of a private medical institute in Karachi: A mixed method study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chandratre, S. Medical students and COVID-19: Challenges and supportive strategies. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520935059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.; Jegatheeswaran, L.; Minocha, A.; Alhilani, M.; Nakhoul, M.; Mutengesa, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: A national survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Q.-H.; Wang, C.-M.; Wang, J. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Du, H.; Li, R.; Kang, L.; Su, M.; et al. Survey of Insomnia and Related Social Psychological Factors among Medical Staff Involved in the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease Outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shpakou, A.; Naumau, I.A.; Krestyaninova, T.Y.; Znatnova, A.V.; Lollini, S.V.; Surkov, S.; Kuzniatsou, A. Physical Activity, Life Satisfaction, Stress Perception and Coping Strategies of University Students in Belarus during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanisławski, K. The Coping Circumplex Model: An Integrative Model of the Structure of Coping with Stress. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D.A. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saczuk, K.; Lapinska, B.; Wilmont, P.; Pawlak, L.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Relationship between Sleep Bruxism, Perceived Stress, and Coping Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Veer, I.M.; Riepenhausen, A.; Zerban, M.; Wackerhagen, C.; Puhlmann, L.; Engen, H.; Köber, G.; Bögemann, S.A.; Weermeijer, J.; Us´ciłko, A.; et al. Psycho-social factors associated with mental resilience in the Corona lockdown. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budimir, S.; Probst, T.; Pieh, C. Coping strategies and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C.; Calderón-Garrido, D. Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education students. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 42, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Erickson, D.J.; Sharkansky, E.J.; King, D.W.; King, L.A. Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder among Gulf War veterans: A prospective analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 67, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creech, S.K.; Benzer, J.K.; Liebsack, B.K.; Proctor, S.; Taft, C.T. Impact of coping style and PTSD on family functioning after deployment in Operation Desert Shield/Storm returnees. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R.R.; Probst, T.M.; Watson, G.P.; Bazzoli, A. Caught between scylla and charybdis: How economic stressors and occupational risk factors influence workers’ occupational health reactions to COVID-19. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Li, S.; Yang, N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e923549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, E.; Di Mattei, V.; Perego, G.; Ferrari, F.; Mazzetti, M.; Taranto, P. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N.; Tripepi, G.; Di Prinzio, R.R. Symptoms in Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic. A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, M.; Arslan, G.; Özaslan, A. Perceived Risk and Mental Health Problems among Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Mediating Effects of Resilience and Coronavirus Fear. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovai, L.; Maremmani, A.G.; Rugani, F.; Bacciardi, S.; Pacini, M.; Dell’Osso, L. Do Akiskal & Mallya’s affective temperaments belong to the domain of pathology or to that of normality? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 17, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer, P. COVID-19 health anxiety. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Hu, S.; Gao, J. Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Drug Discov. Ther. 2020, 14, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guan, W.; Ni, Z.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.; Ou, C.; He, J.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Velden, P.G.; Contino, C.; Das, M.; Van Loon, P.; Bosmans, M.W. Anxiety and depression symptoms, and lack of emotional support among the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A prospective national study on prevalence and risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A crosssectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.; Ripp, J.; Trockel, M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 2133–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baloch, S.; Baloch, M.A.; Zheng, T.; Pei, X. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2020, 250, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asmundson, G.J.G.; Taylor, S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 70, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braibanti, R. Transnational inducement of administrative reform: A survey of scope and critique of issues. In Approaches to Development; Montgomery, J.D., Sffin, W.J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, V.A. Administrative objectives for development administration. Adm. Sci. Q. 1964, 9, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, J.F. Bureaucratic transformation in Burma. In Asian Bureaucratic Systems Emergent from the British Imperial Tradition; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 1966; pp. 354–443. [Google Scholar]

- Pye, L.W. Politics, Personality, and Nation Building: Burma’s Search for Identity, Braibanti, R., Ed.; Yale Univ. Press: New Haven, CN, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Y.; Etgar, S.; Shiffman, N.; Lurie, I. The Fear of COVID-19 Familial Infection Scale: Development and Initial Psychometric Examination. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2022, 55, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Bovin, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Sloan, D.M.; Schnurr, P.P.; Kaloupek, D.G.; Keane, T.M.; Marx, B.P. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol. Assess 2018, 30, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric Indicators to Detect Insomnia Cases and Evaluate Treatment Response. Sleep 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, J.; Chapman, E.; Houghton, S.; Lawrence, D. Development and Validation of a Coping Strategies Scale for Use in Chinese Contexts. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 845769. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 72, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.T. Analysis of formalism’s moderating effect on the relationships between role stressors and work anxiety—Viewpoints from oriental public administration. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Sci. 2015, 26, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.-T. The Influence of Public Servant’s Perceived Formalism and Organizational Environmental Strategy on Green Behavior in Workplace. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.E.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Noboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J.S. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.Y.; Kotabe, M.; Zhou, J.N. Strategic alliance-based sourcing and market performance: Evidence from foreign firms operating in China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Söbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

| Counts | Percentage (%) | Counts | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Seniority | ||||

| Male | 426 | 94.0 % | 1 to 3 years | 115 | 25.4 % |

| Female | 27 | 6.0 % | 4 to 7 years | 98 | 21.6 % |

| Age | 8 to 11 years | 58 | 12.8 % | ||

| 20–29 years old | 131 | 28.9 % | 12 to 15 years | 59 | 13.0 % |

| 30–39 years old | 190 | 41.9 % | 16 years or more | 123 | 27.2 % |

| 40–49 years old | 83 | 18.3 % | Marriage | ||

| 50 years old or older | 49 | 10.8 % | Unmarried | 194 | 42.8 % |

| Education level | Married | 253 | 55.8 % | ||

| Junior college | 198 | 43.7 % | Other | 6 | 1.3 % |

| College | 185 | 40.8 % | Position | ||

| Postgraduate | 70 | 15.5 % | Firefighters | 348 | 76.8 % |

| Sergeant | 62 | 13.7 % | |||

| Station Chief | 43 | 9.5 % |

| Variables | Items | Lambda | Z Value | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of family infection | FFI 1 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| FFI 2 | 0.93 | 172.5 | |||

| FFI 3 | 0.94 | 173 | |||

| FFI 4 | 0.89 | 170.2 | |||

| FFI 5 | 0.90 | 164.2 | |||

| FFI 6 | 0.91 | 166.5 | |||

| FFI 7 | 0.95 | 170.7 | |||

| Fear of self-infection | FSI 1 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.94 | |

| FSI 2 | 0.86 | 188.6 | |||

| FSI 3 | 0.87 | 185.4 | |||

| FSI 4 | 0.94 | 191.6 | |||

| FSI 5 | 0.81 | 177.6 | |||

| FSI 6 | 0.78 | 175.2 | |||

| Formalism | FOR 1 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| FOR 2 | 0.88 | 73 | |||

| FOR 3 | 0.91 | 74.7 | |||

| FOR 4 | 0.83 | 71 | |||

| PTSD | PTSD 1 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| PTSD 2 | 0.79 | 169 | |||

| PTSD 3 | 0.84 | 173.2 | |||

| PTSD 4 | 0.71 | 165 | |||

| PTSD 5 | 0.72 | 172 | |||

| PTSD 6 | 0.78 | 161.7 | |||

| PTSD 7 | 0.82 | 173.7 | |||

| Insomnia | IN 1 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.92 | |

| IN 2 | 0.72 | 159.9 | |||

| IN 3 | 0.81 | 168.3 | |||

| IN 4 | 0.78 | 170.1 | |||

| IN 5 | 0.81 | 161.4 | |||

| IN 6 | 0.84 | 177.5 | |||

| IN 7 | 0.79 | 164.5 | |||

| Problem-focused strategies | PFS 1 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.95 | |

| PFS 2 | 0.80 | 43.9 | |||

| PFS 3 | 0.86 | 44.3 | |||

| PFS 4 | 0.91 | 45.5 | |||

| PFS 5 | 0.93 | 45.2 | |||

| PFS 6 | 0.89 | 45 | |||

| PFS 7 | 0.75 | 42.2 | |||

| COVID-19 stress | COS 1 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.94 | |

| COS 2 | 0.79 | 164.7 | |||

| COS 3 | 0.86 | 175.6 | |||

| COS 4 | 0.74 | 156 | |||

| COS 5 | 0.75 | 161.3 | |||

| COS 6 | 0.85 | 171.4 | |||

| COS 7 | 0.74 | 157 |

| FFI | FSI | FOR | PTSD | IN | PFS | COS | ASV | MSV | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFI | (0.92) | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.84 | ||||||

| FSI | 0.74 | (0.86) | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.73 | |||||

| FOR | 0.34 | 0.32 | (0.88) | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.77 | ||||

| PTSD | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.30 | (0.78) | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.61 | |||

| IN | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.27 | 0.77 | (0.80) | 0.32 | 0.59 | 0.64 | ||

| PFS | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.16 | −0.13 | −0.07 | (0.85) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.73 | |

| COS | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.73 | −0.05 | (0.80) | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.63 |

| Hypothesis | Causal Path | Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | Z Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | COVID-19 stress | → | PTSD | 0.76 ** | 0.03 | 24.91 |

| H2 | COVID-19 stress | → | Insomnia | 0.71 ** | 0.04 | 21.66 |

| H3 | Problem-focused strategies | → | PTSD | −0.08 ** | 0.04 | −2.87 |

| H4 | COVID-19 stress | → | Problem-focused strategies | −0.13 ** | 0.04 | −2.82 |

| H5 | Fear of family infection | → | COVID-19 stress | 0.09 * | 0.04 | 2.03 |

| H6 | Fear of self-infection | → | COVID-19 stress | 0.68 ** | 0.04 | 15.28 |

| H7 | Formalism | → | COVID-19 stress | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | 5.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, Y.-M.; Wu, T.-L.; Liu, H.-T. Causal Model Analysis of the Effect of Formalism, Fear of Infection, COVID-19 Stress on Firefighters’ Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome and Insomnia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021097

Tang Y-M, Wu T-L, Liu H-T. Causal Model Analysis of the Effect of Formalism, Fear of Infection, COVID-19 Stress on Firefighters’ Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome and Insomnia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021097

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Yun-Ming, Tsung-Lin Wu, and Hsiang-Te Liu. 2023. "Causal Model Analysis of the Effect of Formalism, Fear of Infection, COVID-19 Stress on Firefighters’ Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome and Insomnia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021097

APA StyleTang, Y.-M., Wu, T.-L., & Liu, H.-T. (2023). Causal Model Analysis of the Effect of Formalism, Fear of Infection, COVID-19 Stress on Firefighters’ Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome and Insomnia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021097