The Flipped Break-Even: Re-Balancing Demand- and Supply-Side Financing of Health Centers in Cambodia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Funds for the vulnerable: In some countries, governments (or donors) provide special support for vulnerable groups, such as the poor, chronically ill patients, or the disabled. For instance, Cambodia Health Equity Funds (HEFs) entitle selected poor groups to receive free healthcare services. The provider is refunded by the HEF which itself is re-financed by the government and/or a donor [14,22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Financial Analysis

2.3. Break-Even-Analysis

| e* | break-even-point [number of service units] |

| If | fixed income |

| Cf | fixed costs |

| cv | variable cost per contact |

| iv | variable income per contact |

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Income Analysis

3.2. Cost Analysis

3.3. Surplus, Deficit, and Break-Even-Analysis

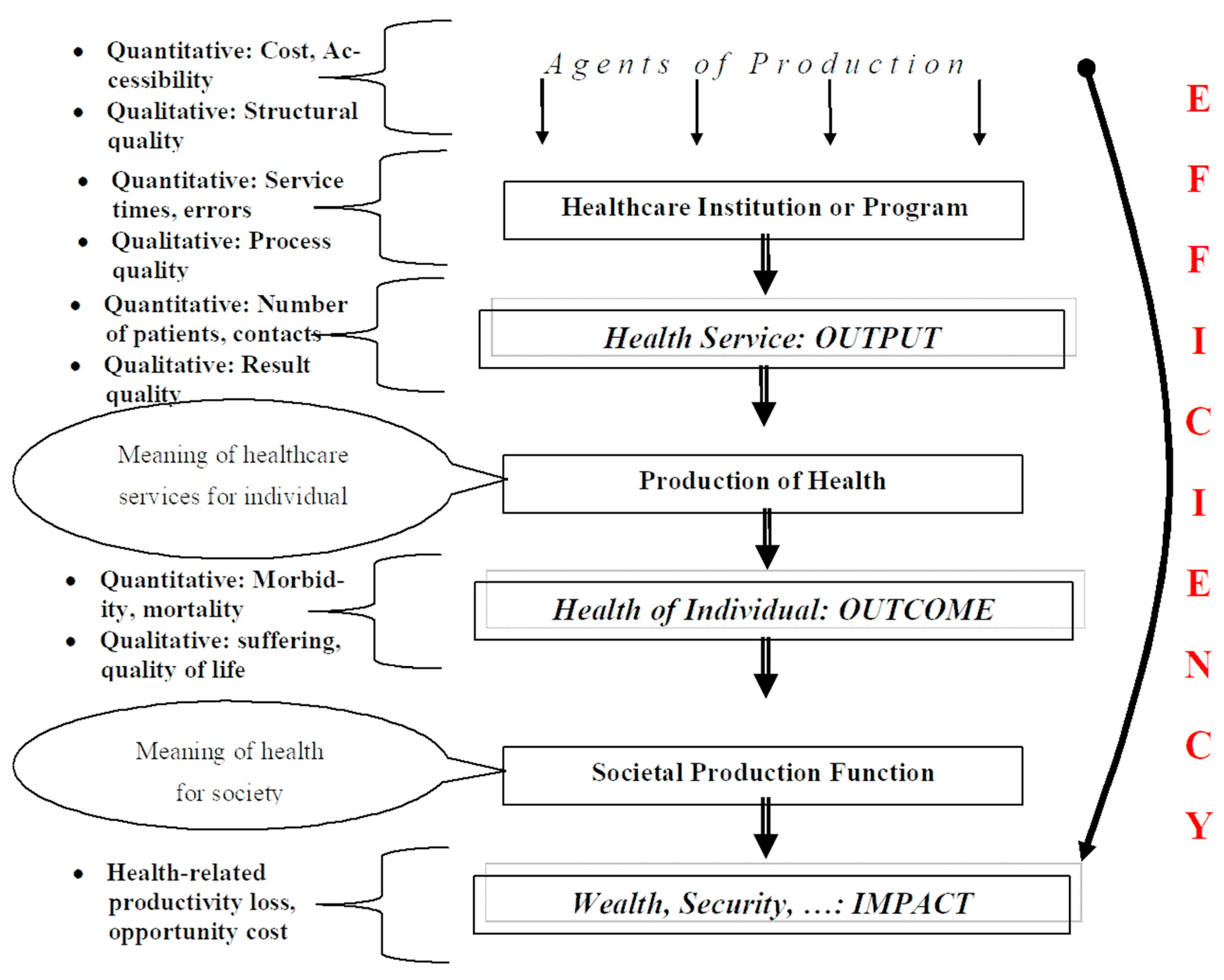

3.4. Quality and Efficiency

4. Discussion

4.1. Health Facility Financing

4.2. Quality and Efficiency

4.3. Limitations

- Quality of data: The collection of data was limited by the Cambodian reality of health facilities and public accounting. We had to use different sources of data, such as public accounts from operational districts, provinces, the MoH, and other organizations (e.g., central medical stores). Payments were accounted for in the place where they are made, and no reconciled accounts exist in Cambodia. In addition, some data had to be collected at the health facility directly from staff, which required personal visits. There was a risk that some data were not precise or might represent only the specific situation of the day of the visit;

- Timeliness: The data were from the financial year 2019. It took about 12 months until data were available after the end of the financial year, and the COVID-19 pandemic delayed some research visits. Thus, the data might not be representative of the current situation;

- Quality: We had to rely on the quality score provided by the National Quality Enhancement Monitoring Tool (NQEMT). This tool is mainly based on structural quality components and might not reflect the result quality sufficiently. This system does not sufficiently take into account the proportion of different services provided, i.e., the quality score cannot reflect the proportion of different services provided. It is possible that a health center could achieve higher quality by providing a higher proportion of less complex services. In principle, the regulations of the government describe precisely the services and service-mix of health centers, but in reality, we found diverging service statistics with an impact on quality score.Furthermore, the quality scores do not deviate very much. It seems that there is a tendency for quality assessment to give rather similar scores. Only one institution has a score higher than 90%, while only two have a score lower than 50%. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this assessment is partially biased;

- Outcome: Quality of services (and in particular structural quality) is only a prerequisite of good outcomes relevant for customers. Others are financial and spatial access, availability of key services, and coverage of key at-risk populations. With the limitations of data availability in Cambodia, we cannot add these additional dimensions.

- Sample: We must address that the sample was drawn from the provinces of Kampot and Kampong Thom. These provinces are not representative of urban areas (in particular Phnom Penh) and very remote areas with very low population density (such as Mondulkiri Province). Thus, any conclusions built on this sample are limited to these provinces.However, in comparison to many other costing studies done in low-income countries, the methodology and the data collection process are quite precise, and much effort was invested to safeguard good quality data so that the results presented above are comparably reliable;

- Average break-even analysis: Another methodological shortcoming is the fact that we developed a break-even analysis for an “average” health center. While we calculated the fixed and variable income and expenditure for each facility, the final result is an “average institution” with a fixed service-mix. This is appropriate to demonstrate the impact of increased workload, but it should not be taken as an accusation against a single health facility. In addition, our explanation that differences in surplus and deficit are mainly due to utilization disregards the fact that these differences could also be explained by differences in the severity of the case-mix;

- Efficiency: The efficiency statistic is built on a rather simple index number as the ratio between the quality score and cost per service unit. The number of service units was calculated as the total of service units for all cost centers. This is a simplification as some facilities might show poor efficiency while they are very efficient in one particular service. Other authors have shown that data envelopment analysis (DEA) can overcome this problem [49], an alternative could be stochastic frontier analysis (SFA). However, the focus of this paper is on the flipped break-even and the impact on the value-for-customer. It should, however, be respected that this limitation must not lead to an accusation against an individual institution. It should, however, open the platform for further discussion on quality, cost, and efficiency between the government and the leadership of health facilities;

- Optimum: The findings of this study demonstrate that Cambodia has a mixed system of lump sum line-item funding and performance-based funding as well as supply-side and demand-side financing of public health centers. The biggest share of income of a public health center is independent of any quantitative or qualitative performance, and the leadership of the facility has very low autonomy over its finances. Our findings cannot indicate an “optimum” ratio between the healthcare financing alternative, but by summarizing the findings, we can state that Cambodia should move towards performance-based financing to improve the value for the customer. There is still a need for line-item budgeting for preventive services and for health facilities in remote areas with a low population density. It might also be wise to provide buildings, equipment, and vehicles based on the population of the catchment area. The government should, however, consider providing funds for staff based on performance criteria.

5. Conclusions

- The results of this paper indicate the relevance of regular routine data collection in the healthcare system of Cambodia, in particular costing and quality of healthcare services as well as their impact on equity and efficiency. This will build the evidence base for re-balancing demand- and supply-side financing and encourage value-based healthcare. Consequently, the results presented here encourage switching from a snapshot-like costing to a routine system based on national samples. In most countries, costing of healthcare services is accepted as a prerequisite of proper healthcare planning. The Royal Government of Cambodia recently presented the “Cambodia PHC Booster Implementation Framework” calling for professional costing in order to “adjust reimbursements rates to the comprehensive cost estimates which should be updated regularly” [50];

- The financial analysis demonstrates that merely 2% of the total income of public health centers comes from the HEF. This surprising statistic indicates that vulnerable groups who are entitled to healthcare without out-of-pocket payments do not seek healthcare at all or find ways to pay for private healthcare services. This goes in line with the findings of other studies showing that the HEF does not necessarily protect the poor as expected [51]. Some authors argue that the HEF card carries a stigma as it indicates that the cardholder is vulnerable [52,53], but our research cannot assess the relevance of this assertion. The under-utilization of healthcare services by the poor and the role of the private sector will require more research;

- The different instruments of healthcare financing presented in Figure 7 show that there are different financing options that can be mixed. For a political discussion, it is crucial to distinguish between the terms and precisely define the meaning of certain concepts. For instance, the terms “demand-side-financing”, “performance-based financing” and “household subsidy” are not strictly defined in Cambodia, leading to misunderstandings. Thus, our findings call for a standardization of terminology at least within the Royal Government of Cambodia and the health partners (donor agencies);

- The efficiency of the health centers can be improved by increasing the variable income. Currently, the public healthcare system is under-financed so that additional funds (e.g., from the National Social Security Fund) will not lead to overfunding of healthcare services. However, if the relevance of demand-side and/or performance-based financing increases we will have to formulate a transition strategy with a stepwise shift from fixed income towards variable income without double financing;

- The transition from supply- to demand-side financing has to be accompanied by quality management measures. Cambodia has embarked on a process for accreditation of healthcare facilities. This development should be continued and strengthened so that supply-side funding becomes more and more performance-based;

- The sample from Kampot and Kampong Thom provinces is not representative of very remote areas with low population density. In some areas, it is impossible to switch more towards demand-side financing as the demand of the small population is too low to safeguard that the facilities could survive without line-item lump sum funding. Public health centers are needed in certain places to allow for acceptable access time, but they will not survive from rebates of the HEF and the NSSF or variable income from the government. These facilities will require a fixed income for the foreseeable future. This calls for a more detailed analysis of specific situations. Again, routine accounting, costing, and quality assessments are prerequisites for these decisions;

- The description of the pathways of information, materials, and funds from the facility to the operational district and from the provincial health department to the MoH indicates that the system is highly complex, slow, and expensive. Systems like that tend to be prone to corruption and mismanagement. Cambodia has started a process of decentralization [54]. There is a clear need to delegate more responsibilities to lower levels, such as operational districts. Public health centers should receive a higher degree of autonomy in order to motivate staff and make better decisions reflecting the particular situation of this facility. Strengthening demand-side and performance-based financing is an important component of this process.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ensor, T.; Tiwari, S. Demand-Side Financing in Health in Low-Resource Settings. In Global Health Economics: Shaping Health Policy in Low-and Middle-Income Countries; Revill, P., Suhrcke, M., Moreno-Serra, R., Sculpher, M., Eds.; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 217–237. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, D.S.; Benjamin, E.R. User fees and health financing in developing countries: Mobilizing financial resources for health. In Health, Nutrition, and Economic Crises: Approaches to Policy in the Third World; Auburn House Publishing: Dover, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 401–424. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.B.; Hsu, J.; Boerma, T. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 546-546A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, M.R.; Harris, J.; Ikegami, N.; Maeda, A.; Cashin, C.; Araujo, E.C.; Takemi, K.; Evans, T.G. Moving towards universal health coverage: Lessons from 11 country studies. Lancet 2016, 387, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleßa, S.; Greiner, W. Grundlagen der Gesundheitsökonomie: Eine Einführung in das wirtschaftliche Denken im Gesundheitswesen, 3rd ed.; Springer Gabler: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte-Tremblay, A.M.; Spagnolo, J.; De Allegri, M.; Ridde, V. Does performance-based financing increase value for money in low-and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Çelik, Y.; Khan, M.; Hikmet, N. Achieving value for money in health: A comparative analysis of OECD countries and regional countries. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2017, 32, e279–e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Guth, C. Redefining German Health Care: Moving to a Value-Based System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Claeson, M.; Griffin, C.G.; Johnston, T.A.; McLachlan, M.; Soucat, A.; Wagstaff, A.; Yazbeck, A. Health, nutrition and population. In A Sourcebook for Poverty Reduction Strategies; Bank, T.W., Ed.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 201–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, R.J.; Powell-Jackson, T.; Kristensen, S.R.; Singh, N.; Borghi, J. How are pay-for-performance schemes in healthcare designed in low-and middle-income countries? Typology and systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalyst. What Is Value-Based Healthcare? Available online: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0558 (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Rawlings, L.B.; Rubio, G.M. Evaluating the impact of conditional cash transfer programs. World Bank Res. Obs. 2005, 20, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes Antunes, A.; Jacobs, B.; de Groot, R.; Thin, K.; Hanvoravongchai, P.; Flessa, S. Equality in financial access to healthcare in Cambodia from 2004 to 2014. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitehead, M.; Bird, P. Breaking the poor health–poverty link in the 21st Century: Do health systems help or hinder? Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2006, 100, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenny, A.P.; Yates, R.; Thompson, R. Social Health Insurance Schemes in Africa Leave out the Poor; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 10; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bigdeli, M.; Jacobs, B.; Men, C.R.; Nilsen, K.; Van Damme, W.; Dujardin, B. Access to treatment for diabetes and hypertension in rural Cambodia: Performance of existing social health protection schemes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Allegri, M.; Sauerborn, R.; Kouyaté, B.; Flessa, S. Community health insurance in sub-Saharan Africa: What operational difficulties hamper its successful development? Trop. Med. Int. Health 2009, 14, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S.; Walker, D.G. Trust in the context of community-based health insurance schemes in Cambodia: Villagers’ trust in health insurers. In Innovations in Health System Finance in Developing and Transitional Economies; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bellows, B.; Kyobutungi, C.; Mutua, M.K.; Warren, C.; Ezeh, A. Increase in facility-based deliveries associated with a maternal health voucher programme in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2013, 28, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bajracharya, A.; Veasnakiry, L.; Rathavy, T.; Bellows, B. Increasing uptake of long-acting reversible contraceptives in Cambodia through a voucher program: Evidence from a difference-in-differences analysis. Glob. Health: Sci. Pract. 2016, 4, S109–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hardeman, W.; Van Damme, W.; Van Pelt, M.; Por, I.; Kimvan, H.; Meessen, B. Access to health care for all? User fees plus a Health Equity Fund in Sotnikum, Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2004, 19, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman, K. Strengths and weaknesses of financing hospitals in Germany. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Khun, S.; Manderson, L. Poverty, user fees and ability to pay for health care for children with suspected dengue in rural Cambodia. Int. J. Equity Health 2008, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, B.; Bajracharya, A.; Saha, J.; Chhea, C.; Bellows, B.; Flessa, S.; Antunes, A.F. Making free public healthcare attractive: Optimizing health equity funds in Cambodia. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NSSF. National Social Security Fund. Available online: http://www.nssf.gov.kh/default/about-us-2/history/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Kolesar, R.J.; Pheakdey, S.; Jacobs, B.; Chan, N.; Yok, S.; Audibert, M. Expanding social health protection in Cambodia: An assessment of the current coverage potential and gaps, and social equity considerations. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2020, 73, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Institute of Statistic. General Population Census of the Kingdom of Cambodia, National Report on Final Census Results. Available online: http://nis.gov.kh/index.php/en/15-gpc/79-press-release-of-the-2019-cambodia-general-population-census (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- National Institute of Statistics. Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2021-2022. Key Indicator Report. Available online: https://nis.gov.kh/index.php/en/17-cdhs/107-cambodia-demographic-and-health-survey-2021-22-key-indicator-report (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Ministry of Health. Summary Report on Health Progress for the Year 2021. Available online: http://digital-hosp.com/library/index.php (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Department of Planning and Health Information. Guideline for Developing Operational Districts. Available online: http://digital-hosp.com/library/index.php# (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Flessa, S.; Moeller, M.; Ensor, T.; Hornetz, K. Basing care reforms on evidence: The Kenya health sector costing model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minh, H.V.; Giang, K.B.; Huong, D.L.; Huong, L.T.; Huong, N.T.; Giang, P.N.; Hoat, L.N.; Wright, P. Costing of clinical services in rural district hospitals in northern Vietnam. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2010, 25, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Ali, B.; Naeem, A.; Vassall, A. Using costing as a district planning and management tool in Balochistan, Pakistan. Health Policy Plan. 2001, 16, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conteh, L.; Walker, D. Cost and unit cost calculations using step-down accounting. Health Policy Plan. 2004, 19, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, D.A.; Flessa, S.; Marschall, P.; Ha, S.T.; Luong, K.N.; Busse, R. Determining the impacts of hospital cost-sharing on the uninsured near-poor households in Vietnam. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flessa, S.; Dung, N.T. Costing of services of Vietnamese hospitals: Identifying costs in one central, two provincial and two district hospitals using a standard methodology. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2004, 19, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M. A Textbook of cost and Management Accounting; Vikas Publishing House: Mumbai, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Horngren, C.T. Management and Cost Accounting, 3rd, ed.; Prentice Hall/Financial Times: Harlow, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian, A. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring. Vol. I: The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment; Health Administration Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1980; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Flessa, S. The costs of hospital services: A case study of Evangelical Lutheran Church hospitals in Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 1998, 13, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donabedian, A. Methods for deriving criteria for assessing the quality of medical care. Med. Care Rev. 1980, 37, 653–698. [Google Scholar]

- Walsham, M. HEF/Voucher Integration in Kampong Thom Health Equity Funds Utilization Survey: Are Beneficiaries Enjoying their Benefits? Consultancy Report; Mai: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bellows, N.M.; Bellows, B.W.; Warren, C. Systematic Review: The use of vouchers for reproductive health services in developing countries: Systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaan, E.; Mathijssen, J.; Tromp, N.; McBain, F.; Have, A.t.; Baltussen, R. The impact of health insurance in Africa and Asia: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.-L.; Griffin, C.C.; Shaw, R.P. The Impact of Health Insurance in Low-And Middle-Income Countries; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Direct Facility Financing: Concept and Role for UHC. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240043374 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Wiseman, V.; Asante, A.; Ir, P.; Limwattananon, S.; Jacobs, B.; Liverani, M.; Hayen, A.; Jan, S. System-wide analysis of health financing equity in Cambodia: A study protocol. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolesar, R.J.; Bogetoft, P.; Chea, V.; Erreygers, G.; Pheakdey, S. Advancing universal health coverage in the COVID-19 era: An assessment of public health services technical efficiency and applied cost allocation in Cambodia. Health Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoH. Cambodia PHC Booster Implementation Framework; Information DoPaH, Ed.; Royal Government of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Annear, P.L.; Lee, J.T.; Khim, K.; Ir, P.; Moscoe, E.; Jordanwood, T.; Lo, V. Protecting the poor? Impact of the national health equity fund on utilization of government health services in Cambodia, 2006–2013. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdeli, M.; Annear, P.L. Barriers to access and the purchasing function of health equity funds: Lessons from Cambodia. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feldhaus, I.; Nagpal, S.; Bauhoff, S. Role of User Benefit Awareness in Health Coverage Utilization among the Poor in Cambodia. Health Syst. Reform 2022, 8, e2058336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, J.; Chakrabarti, B. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through decentralisation and the role of local governments: A systematic review. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Provinces | Operational District | N | Name of Health Center |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kampot | Kampong Trach | 12 | Ang Sorphy, Boeng Sala, Banteay Meas, Prek Kreus, Sdach Kong, Srae Chea, Svay Tong, Tnoat Chong Srang, Prey Tonle, Phnom Lo Ngeang, Russei Srok Keut, Kampong Trach |

| Angkor Chey | 9 | Ang Phnom Toch, Deum Dong, Samrong Leu, Champei, Wat Ang, Dan Koum, Sam Larnh, Pra Phnum, Trapaing Sala | |

| Kampong Thom | Kampong Thom | 17 | Tboung Krapeu, Srayov, Prey Kuy, Damrei Choan Khla, Kampong Thom, Achar Leak, Ka Koh, Kampong Ko, Kampong Svay, Damrei Slab, Sandan (with beds), Chheu Teal, Mean Chey, Chhouk, Taing Krasao, Sala Visai (with beds), Sambor (with beds) |

| Baray-Santuk | 19 | Ti Pou, Pra Sat, Kampong Thmor, L’ak, Thnoat Chum, Balangk, Chaeung Daeung, Krava, Beoung, Chhouk Ksach, Baray, Sralau, Kreul, Srah Banteay, Pratoang, Kork Trabaek, Pong Ro, Korki Thom, Chong Dong |

| Demand-Side Financing | Supply-Side Financing | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lump Sum Financing | Salaries and wages: 41.21% Investments: 4.13% Other lump sums: 6.49% | 51.83% | |

| Performance-Based Financing | Direct patient fees: 3.76% HEF: 1.99% NSSF: 0.27% Other: 0.05% | Drugs, materials, vaccines: 32.71% Mid-wife allowances: 9.39% | 48.17% |

| Total | 6.07% | 93.93% | 100% |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | y-Intercept [p%] | Slope [p %] | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unit cost | quality | 0.75 [<0.01] | 0 [0.64] | 0.00 |

| unit cost | efficiency | 0.23 [<0.01] | −0.01 [<0.01] | 0.66 |

| efficiency | quality | 0.71 [<0.01] | 0.22 [0.25] | 0.02 |

| margin | quality | 0.68 [<0.01] | 0.02 [0.04] | 0.07 |

| margin | efficiency | 0.20 [<0.01] | −0.02 [< 0.01] | 0.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koy, S.; Fuerst, F.; Tuot, B.; Starke, M.; Flessa, S. The Flipped Break-Even: Re-Balancing Demand- and Supply-Side Financing of Health Centers in Cambodia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021228

Koy S, Fuerst F, Tuot B, Starke M, Flessa S. The Flipped Break-Even: Re-Balancing Demand- and Supply-Side Financing of Health Centers in Cambodia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021228

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoy, Sokunthea, Franziska Fuerst, Bunnareth Tuot, Maurice Starke, and Steffen Flessa. 2023. "The Flipped Break-Even: Re-Balancing Demand- and Supply-Side Financing of Health Centers in Cambodia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021228

APA StyleKoy, S., Fuerst, F., Tuot, B., Starke, M., & Flessa, S. (2023). The Flipped Break-Even: Re-Balancing Demand- and Supply-Side Financing of Health Centers in Cambodia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021228