Onboarding in Polish Enterprises in the Perspective of HR Specialists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Considerations

2.1. The Concept of Onboarding

2.2. Levels, Components, and Types of Onboarding

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Area

- What type of onboarding is most common in different types of Polish enterprises?

- Does the preference for particular onboarding practices depend on the gender, age, and seniority of an HR specialist who prepares and implements the onboarding process in an enterprise?

- Does the introduction of a buddy practice depend on the type of enterprise?

3.2. Research Tool

- A referral to pre-employment medical examination.

- Handing tools/equipment necessary for performing the job (e.g., laptop, phone, clothing).

- Granting access to places and services necessary for performing the job (e.g., parking lot, employee ID card, email address).

- Providing information on the company’s values, vision, and mission.

- Ensuring that employee hiring formalities are completed properly.

- Providing information on the company’s policies, procedures, and regulations.

- Providing information on the departments or organizational units that are the most important from the point of view of an employee’s position.

- Providing information on an employee’s duties and ways of performing them.

- Introducing employees to their superiors.

- Introducing employees to their department/team.

4. Results

4.1. The Type of Company (in Which an HR Specialist Works) and the Type of Onboarding Implemented

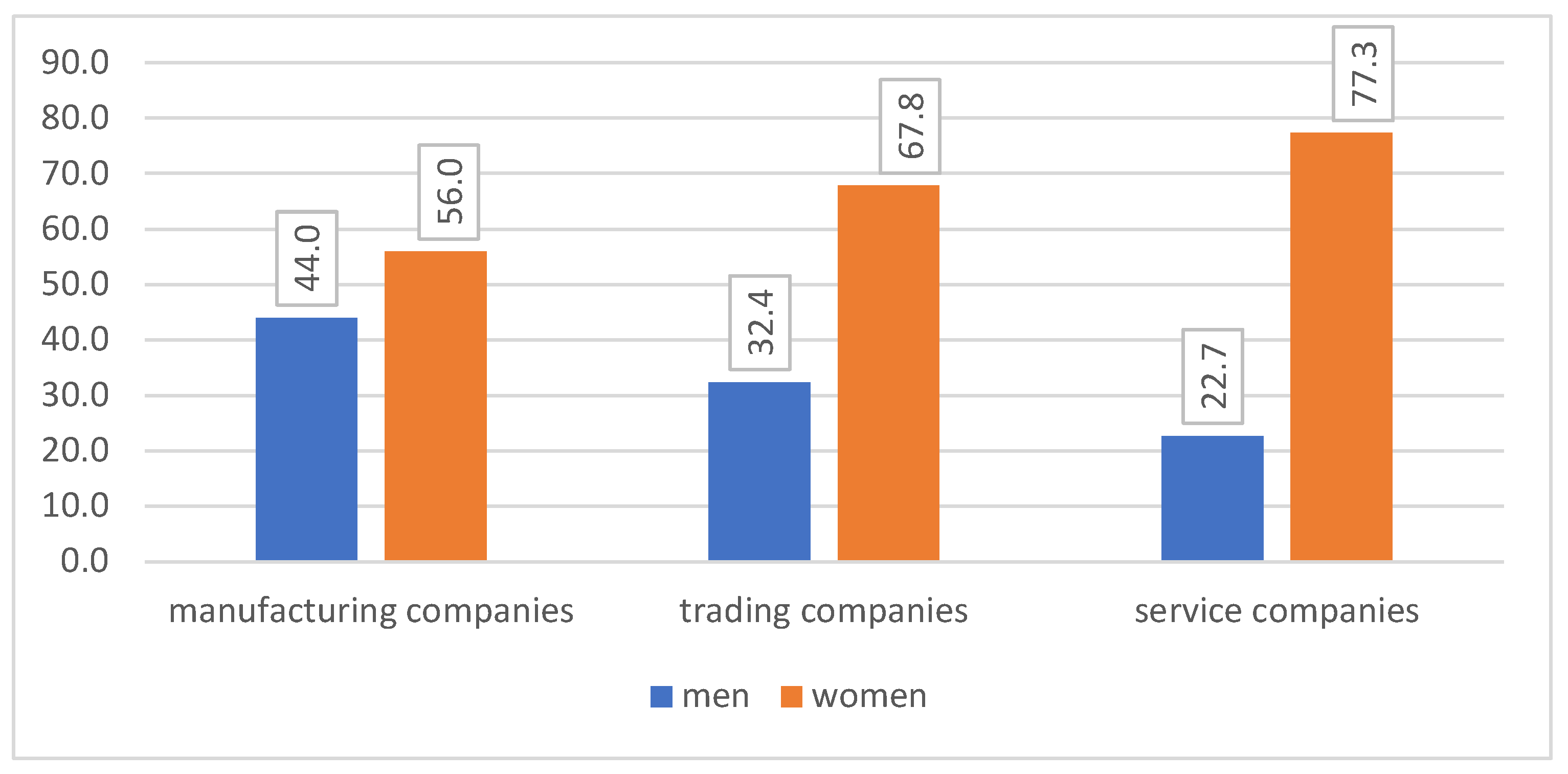

4.2. Characteristics of the Respondents

4.3. Preference for Particular Onboarding Practices and Respondents’ Gender

4.4. Preference for Particular Onboarding Practices and the Respondents’ Age

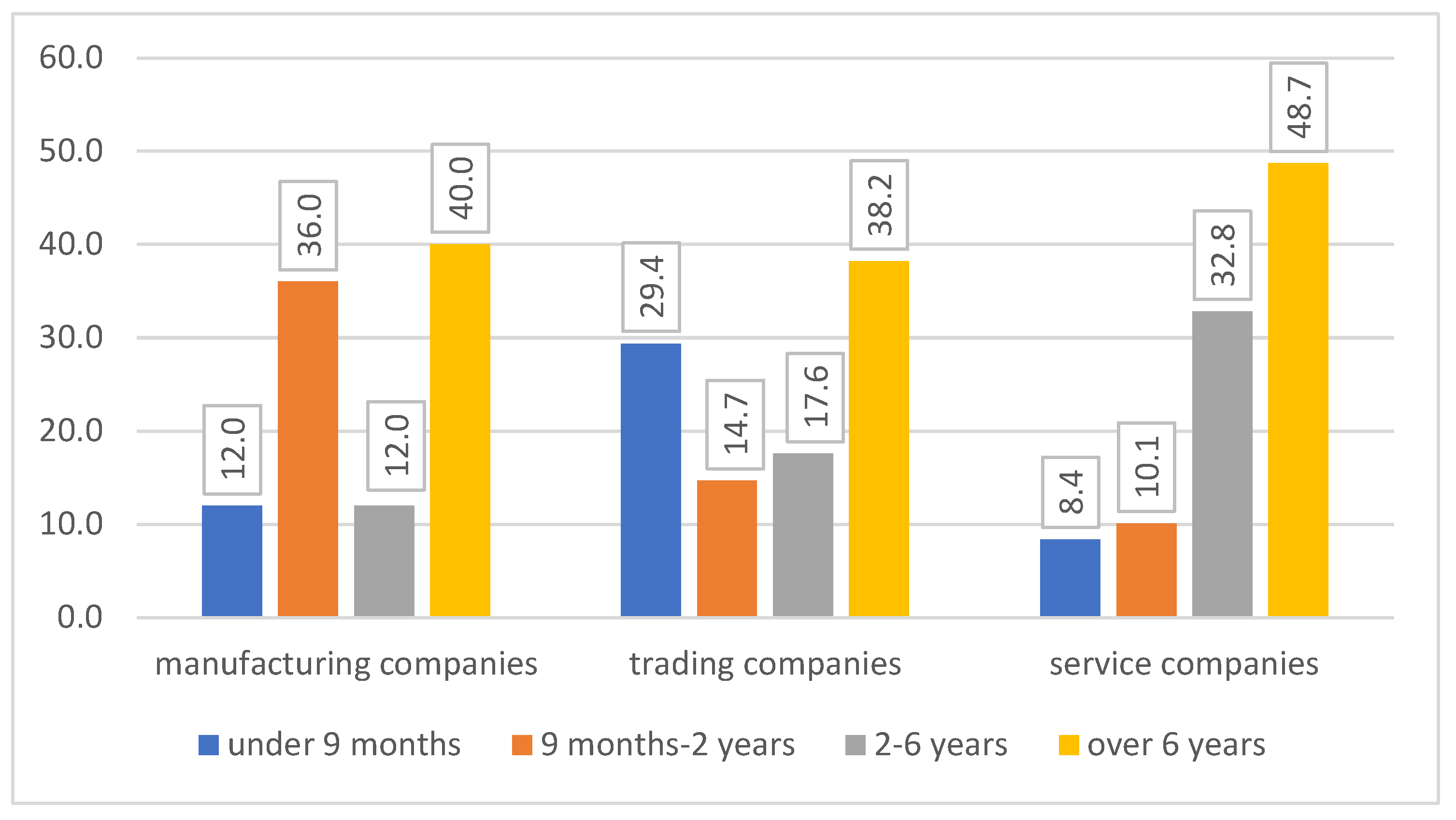

4.5. Preference for Particular Onboarding Practices and the Respondents’ Work Experience (Seniority)

4.6. The Type of Company and Assignment of a Buddy

4.7. Summary

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Ethical Aspect of the Study, and Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A.; Dachowski, R.; Gałek, K.; Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P. Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards Knowledge Workers aged 65 plus in the Context of Their Good Employment Practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 280 Pt 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Yang, S.; Liu, Q.; Feng, S.C. Sustainable development and health assessment model of higher education in India: A mathematical modeling approach. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covey, S.R. Przywództwo Skoncentrowane na Zasadach; Audiobook, Wydawnictwo Aleksandria: Katowice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, T. Toward Sustainable Wellbeing: Advances in Contemporary Concepts. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 807984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. The Effect of Psychological Contract Combined with Stress and Health on Employees’. Management Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 667302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, G. Zatrudnianie Pracowników Wiedzy 65 Plus. Perspektywa Pracowników I Organizacji; Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-83-8019-290-4. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, B.; Huselid, M. Strategic human resources management: Where do we go from here? J. Manag. 2006, 32, 898–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages, The role of the ‘strength’ of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, C.; Super, J.F.; Kwon, K. Resource orchestration in practice: CEO emphasis on SHRM, commitment-based HR systems, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, T.R.; Combs, J.G.; Todd, S.; Woehr, D.J. Does human capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between human capital and firm performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D. Human resource management and performance: Still searching for some answers. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2011, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.; Lepak, D.; Schneider, B. Employee attributions of the ‘why’ of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Nguyen, C.; Ngo, T.; Nguyen, L.V. The Effects of Job Crafting on Work Engagement and Work Performance: A Study of Vietnamese Commercial Banks. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez de Pablos, P.; Lytras, M.D. Competencies and human resource management: Implications for organizational competitive advantage. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paauwe, J. HRM and performance: Achievements, methodological issues and prospects. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccei, R.E.; van de Voorde, F.C.; van Veldhoven, M.M.J.P. HRM, well-being andperformance: A theoretical and empirical review. In HRM & Performance: Achievements and Challenges; Paauwe, J., Guest, D.E., Wright, P.M., Eds.; Wiley: London, UK, 2013; pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Aryee, S.; Law, K. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J.G. Well-being and organizational performance: An organizational-level test of the happy-productive worker hypothesis. Work Stress 2009, 23, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villajos, E.; Tordera, N.; Peiró, J.M. Human resource practice, eudaimonic well-being, and creative performance: The mediating role of idiosyncratic deals for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Gardner, T.; Moynihan, L.; Allen, M. The HR performance relationship: Examining causal direction. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 409–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkman, I.; Fan, X.C. Human resource management and the performance of Western firm in China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from New Zealand. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIPD. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development Survey Report: Resourcing and Talent Planning; CIPD: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Report Global Human Capital Trends: Leading the New World of Work; Deloitte University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cattermole, G. Developing the employee lifecycle to keep top talent. Strateg. HR Rev. 2019, 1, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachner, A.M.; Ellingson, J.E.; Noe, R.A.; Saxton, B.M. The future of employee development. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 31, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S. Attracting and Retaining Talent. Total Reward Strategy. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Interdiscip. Res. 2014, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J.K. A “coalesced framework” of talent management and employee performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2015, 64, 544–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, L. Slash graduate recruitment at your peril: Firms advised to plan for the future. People Manag. 2009, 15, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbi, F.; Ahad, N.; Kousar, T.; Ali, T. Talent management as a source of competitive advantage. J. Asian Bus. Strategy 2015, 5, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, C. Managing talented employees. In Human Resources Development; Carbery, R., Cross, C., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2015; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E.; Tarique, I. Global talent management and global talent challenges: Strategic opportunities for IHRM. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybill, J.; Carpenter, M.; Offord, J., Jr.; Piorun, M.; Shaffer, G. Employee onboarding: Identification of best practices in ACRL libraries. Libr. Manag. 2013, 34, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. Do organizational socialization tactics influence newcomer embeddedness and turnover? J. Manag. 2006, 32, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradt, G.; Vonnegut, M. Onboarding: How to Get Your New Employees Up to Speed in Half the Time; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; van Vianen, A.; Anderson, N. Changes in person-organization fit: The impact of socialization tactics on perceived and actual P-O fit. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2004, 13, 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Cable, D.M.; Kim, S. Socialization tactics, employee proactivity, and person-organization fit. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Uggerslev, K.L.; Fassina, N.E. Socialization tactics and newcomer adjustment: A meta-analytic review and test of a model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 70, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N. Onboarding New Employees: Maximizing Success; SHRM Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, C.; Peters, R. New employee onboarding-psychological contracts and ethical perspectives. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, J. Social and Professional Adaptation of Employees as a Main Factor in Shaping Working Conditions. J. US-China Public Adm. 2015, 12, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: Meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, D. Hiring new staff? Aim for success by onboarding. J. Med. Pract. Manag. 2015, 31, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Westerman, J.F.; Cyr, L.A. An Integrative Analysis of Person-Organization Fit Theories. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2004, 12, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Christiansen, L. Successful onboarding. In A Strategy to Unlock Hidden Value within Your Organization; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frear, S. Comprehensive Onboarding, Traction to Engagement in 90 Days; Human Capital Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Badshah, W.; Bulut, M. Onboarding—The Strategic Tool of Corporate Governance for Organizational Growth. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 59, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; DiPiro, J.T. Evaluation of a Structured Onboarding Process and Tool for Faculty Members in a School of Pharmacy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Erdogan, B. Organizational socialization: The effective onboarding of new employees. In APA Handbook of I/O Psychology; Zedeck, S., Aguinis, H., Cascio, W., Gelfand, M., Leung, K., Parker, S., Zhou, J., Eds.; APA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume III, pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta, K.; Medina, M.S. Preboarding, orientation, and onboarding of new pharmacy faculty during a global pandemic. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byford, M.; Watkins, M.D.; Triantogiannis, L. Onboarding isn’t enough. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2017, 95, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario, F.; Chambel, M.J. On-boarding new employees: A three-component perspective of welcoming. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 1465–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Davila, N.; Pina-Ramirez, W. Let’s talk about onboarding metrics. TD Talent Dev. 2018, 72, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.J.; Polin, B.; Sutton, K.L. Specific Onboarding Practices for the Socialization of New Employees. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2015, 23, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasman, M. Three Must-Have Onboarding Elements for New and Relocated Employees. Employ. Relat. Today 2015, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurano, M. Onboarding: The Missing Link to Productivity; Aberdeen Group: Fort Wayne, IN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.M.; Bartels, L.K. The impact of onboarding levels on perceived utility, organizational commitment, organizational support, and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 17, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, L. Virtual improvement: Advising and onboarding during a pandemic. Honor. Pract. 2021, 17, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Petrilli, S.; Galuppo, L.; Ripamonti, S.C. Digital Onboarding: Facilitators and Barriers to Improve Worker Experience. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziden, A.A.; Joo, O.C. Exploring Digital Onboarding for Organizations: A Concept Paper. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 13, 734–750. [Google Scholar]

- Bielski, L. Getting to “yes” with the right candidates: Best practice tips on recruiting and “onboarding” look at process and technology in balance. Am. Bank. Assoc. Bank. J. 2007, 99, 30–34, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; Gino, F.; Staats, B.R. Reinventing employee onboarding. MIT Manag. Rev. 2013, 54, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.; Wanberg, C.; Rubenstein, A.; Song, Z. Support, undermining, and newcomer socialization: Fitting in during the first 90 days. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1104–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, H.R.; Curran, J. Building a Research Onboarding Program in a Pediatric Hospital: Filling the Orientation Gap with Onboarding and Just-in-Time Education. J. Res. Adm. 2018, 2, 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wanous, J.P. Organizational Entry: Recruitment, Selection, Orientation, and Socialization of Newcomers, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M. The relationship between the amount helpfulness of entry training and work outcomes. Hum. Relat. 1996, 49, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellice, M. Orientation and Onboarding Processes for the Experienced Perioperative RN. AORN J. 2013, 98, C5–C6. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, E.F. New employee development: A review and reconceptualization. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 1996, 7, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.J.; Polin, B. Are organizations on board with best practices onboarding? In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 267–287. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.J.; Weaver, N.A. The effectiveness of an organizational-level orientation training program in the socialization of new hires. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigna, B. Getting onboard: Integrating and engaging new employees. Gov. Financ. Rev. 2009, 25, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- PwC Report “Saratoga Human Capital Benchmarking 2015”. 2015. Available online: https://www.pwc.pl/pl/zarzadzanie-kapitalem-ludzkim/assets/pwc-saratoga-hc-benchmarking-2015.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Holmes, T.H.; Rahe, R.H. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1967, 11, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everson, K. Nike’s Andre Martin: Just Learn It. Chief Learning Officer, 2015. Available online: http://www.clomedia.com/articles/6377-nikes-andre-martin-justlearn-it (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Bauer, T.N.; Morrison, E.; Callister, R. Socialization research: A review and directions for future research. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management; Ferris, G.R., Rowland, K.M., Eds.; JAI: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 149–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.; Parsons, C. Socialization tactics and person-organization fit. Pers. Psychol. 2001, 54, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsek, K. Onboarding pracowników—Znajomość procesu, doświadczenia i znaczenie w świetle badań empirycznych. Przedsiębiorczość I Zarządzanie 2018, 19 Pt 1, 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wąsek, K. Onboarding pracowników—Propozycja narzędzia pomiaru. Różnorodność kapitału ludzkiego i jego pomiar—Perspektywa zrównoważonego rozwoju. In Zarządzanie Kapitałem Ludzkim—Wyzwania; Cewińska, J., Krejner-Nowecka, A., Winch, S., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Serafin, K. Kultura organizacyjna jako element wspierający realizację strategii przedsiębiorstwa. In Studia Ekonomiczne; Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2015; pp. 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lawong, D.; Ferris, G.R.; Hochwater, W.; Maher, L. Recruiter political skill and organization reputation effects on job applicant attraction in the recruitment process: A multi-study investigation. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolocha, C.B. Influence of employee-focused corporate social responsibility and employer brand on turnover intention. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, R.; Knox, S. Motivating employees to “live the brand”: A comparative case study of employer brand attractive-ness within the firm perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 2009, 25, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Tikoo, S. Conceptualising and researching employer branding. Career Dev. Int. 2004, 9, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knap-Stefaniuk, A.; Sowa-Behtane, E. Challenges of working in multicultural environment from the perspective of members of intercultural teams. In Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development during Global Challenges; Soliman, K., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): Cordoba, Spain, 2020; pp. 7325–7336. ISBN 978-0-9998551-4-1. [Google Scholar]

- Knap-Stefaniuk, A. Opinions of European managers on challenges in contemporary cross-cultural management. In Innovation Management and Sustainable Economic Development in the Era of Global Pandemic; Soliman, K., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): Cordoba, Spain, 2021; pp. 512–521. ISBN 978-0-9998551-7-1. [Google Scholar]

- Noe, R.; Clarke, A.; Klein, H. Learning in the Twenty- First-Century Workplace. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Saxena, N. The Role of Psychology in Human Resource Management: A Study of the Changing Needs in Managing Workforce in Organizations. J. Soft Ski. Hyderabad 2022, 16, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak, G. Job Crafting. Kształtowanie Podmiotowości Pracy—Perspektywa Pedagogiki Pracy I Psychologii Organizacji; Wydawnictwo Akademii Marynarki Wojennej: Gdynia, Poland, 2021; pp. 111–119. ISBN 978-83-961549-0-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A. Job crafting wśród polskich przedsiębiorców przedstawicieli kadry kierowniczej. Przejawy i uwarunkowania. Zasoby ludzkie-najmocniejszy potencjał organizacji. Sukces organizacji. Zarządzanie I Finans. 2018, 16 Pt 2, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A.; Dama, S.; Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P.; Gaweł-Luty, E. Academic Teachers about Their Productivity and a Sense of Well-Being in the Current COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franfort-Nachmias, C.; Frankfort, D. Metody Badawcze w Naukach Społecznych; Wydawnictwo Zysk i S-ka: Poznań, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pilch, T.; Lalak, D. Strategie badawcze w pedagogice. In Encyklopedia Pedagogiczna XXI Wieku, T.V.; Wydawnictwo Akademickie “Żak”: Warszawa, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Danvila-del-Valle, I.; Lara, F.J.; Marroquin-Tovar, E.; Zegarra, S.; Pablo, E. How Innovation Climate Drives Management Styles in Each Stage of the Organization Lifecycle: The Human Dimension at Recruitment Process. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1198–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Company | General | Team | Position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | Mean | 4,0800 | 1,8400 | 2,5600 |

| N | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,32035 | 0.37417 | 0.86987 | |

| Trading | Mean | 4,1471 | 1,7353 | 2,5882 |

| N | 34 | 34 | 34 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,15817 | 0.61835 | 0.95719 | |

| Service | Mean | 4,0588 | 1,7983 | 2,6050 |

| N | 119 | 119 | 119 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,36104 | 0.53011 | 0.69158 | |

| Total | Mean | 4,0787 | 1,7921 | 2,5955 |

| N | 178 | 178 | 178 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,31248 | 0.52781 | 0.76975 | |

| Gender | 1 * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Mean | 4,38 | 4,0000 | 3,8537 | 3,5714 | 4,0238 | 4,0000 | 4,1875 | 3,6053 | 3,9130 | 3,8043 |

| N | 42 | 43 | 41 | 35 | 42 | 46 | 48 | 38 | 46 | 46 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,147 | 1,17514 | 1,25620 | 1,37810 | 1,27811 | 1,36626 | 1,29904 | 1,30569 | 1,29660 | 1,34362 | |

| Woman | Mean | 4,50 | 4,0777 | 4,2970 | 3,9278 | 3,9035 | 4,0734 | 4,1810 | 3,8384 | 3,9832 | 4,0088 |

| N | 108 | 103 | 101 | 97 | 114 | 109 | 116 | 99 | 119 | 114 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,164 | 1,28100 | 1,14494 | 1,31694 | 1,38876 | 1,31026 | 1,29614 | 1,38289 | 1,30827 | 1,30686 | |

| Total | Mean | 4,47 | 4,0548 | 4,1690 | 3,8333 | 3,9359 | 4,0516 | 4,1829 | 3,7737 | 3,9636 | 3,9500 |

| N | 150 | 146 | 142 | 132 | 156 | 155 | 164 | 137 | 165 | 160 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,157 | 1,24724 | 1,19081 | 1,33746 | 1,35684 | 1,32309 | 1,29300 | 1,36119 | 1,30146 | 1,31656 | |

| Type of Statistics Used | 1 * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney’s U | 2083,000 | 2057,000 | 1595,500 | 1424,000 | 2286,000 | 2440.000 | 2783,000 | 1663,000 | 2613,500 | 2361,500 |

| Wilcoxon’s W | 2986,000 | 3003,000 | 2456,500 | 2054,000 | 8841,000 | 3521,000 | 3959,000 | 2404,000 | 3694,500 | 3442,500 |

| Z | −1,069 | −0.737 | −2,384 | −1,492 | −0.466 | −0.290 | −0.004 | −1,104 | −0.483 | −1,059 |

| Asymptotic significance (2-sided) | 0.285 | 0.461 | 0.017 | 0.136 | 0.641 | 0.772 | 0.997 | 0.270 | 0.629 | 0.289 |

| Age | 1 * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 25 | Mean | 4,50 | 4,5385 | 4,1667 | 3,8500 | 3,8889 | 4,2000 | 4,3333 | 3,8462 | 4,1786 | 4,1538 |

| N | 22 | 26 | 30 | 20 | 27 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 28 | 26 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,185 | 0.81146 | 0.94989 | 1,30888 | 1,08604 | 1,08012 | 1,00000 | 1,18970 | 0.90487 | 0.92487 | |

| 25–30 | Mean | 4,58 | 4,0000 | 4,5417 | 4,2400 | 4,3704 | 4,2308 | 4,5556 | 4,1250 | 4,1538 | 4,1852 |

| N | 24 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 27 | 24 | 26 | 27 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.929 | 1,26491 | 0.88363 | 1,12842 | 1,07946 | 1,10662 | 1,01274 | 0.99181 | 1,18970 | 1,03912 | |

| 31–35 | Mean | 4,64 | 3,6364 | 4,0000 | 4,1000 | 3,7500 | 4,0000 | 4,0833 | 3,4545 | 3,9091 | 4,5000 |

| N | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.924 | 1,43337 | 1,48324 | 1,10050 | 1,48477 | 1,41421 | 1,37895 | 1,57249 | 1,57826 | 1,08012 | |

| 36–40 | Mean | 4,47 | 3,8333 | 4,3333 | 4,3333 | 4,1176 | 4,1875 | 4,0556 | 3,8182 | 3,8947 | 3,7895 |

| N | 19 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 18 | 11 | 19 | 19 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,264 | 1,72354 | 1,29099 | 1,29099 | 1,45269 | 1,32759 | 1,47418 | 1,53741 | 1,62941 | 1,58391 | |

| 41–45 | Mean | 4,39 | 4,0154 | 4,0161 | 3,5000 | 3,7808 | 3,9221 | 4,0500 | 3,6615 | 3,8519 | 3,7692 |

| N | 74 | 65 | 62 | 62 | 73 | 77 | 80 | 65 | 81 | 78 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,237 | 1,17915 | 1,31189 | 1,41131 | 1,48368 | 1,45788 | 1,40433 | 1,48194 | 1,34268 | 1,44979 | |

| Total | Mean | 4,47 | 4,0548 | 4,1690 | 3,8333 | 3,9359 | 4,0516 | 4,1829 | 3,7737 | 3,9636 | 3,9500 |

| N | 150 | 146 | 142 | 132 | 156 | 155 | 164 | 137 | 165 | 160 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,157 | 1,24724 | 1,19081 | 1,33746 | 1,35684 | 1,32309 | 1,29300 | 1,36119 | 1,30146 | 1,31656 | |

| Type of Statistics Used | 1 * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal–Wallis’ H | 0.499 | 5,312 | 5,258 | 10.079 | 5,242 | 1,162 | 4,104 | 1,603 | 1,790 | 4,122 |

| Df | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Asymptotic significance | 0.974 | 0.257 | 0.262 | 0.039 | 0.263 | 0.884 | 0.392 | 0.808 | 0.774 | 0.390 |

| Seniority | Statistics | 1 * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 9 months | Mean | 4,33 | 4,3684 | 4,1905 | 4,0000 | 4,0455 | 4,1579 | 4,2857 | 3,5500 | 4,0952 | 4,1053 |

| N | 15 | 19 | 21 | 17 | 22 | 19 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 19 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,397 | 0.89508 | 1,03049 | 1,22474 | 0.95005 | 1,16729 | 1,00712 | 1,39454 | 1,17918 | 1,04853 | |

| 9 months–2 years | Mean | 4,83 | 4,1667 | 4,1600 | 3,7500 | 3,9545 | 4,3333 | 4,4583 | 4,1304 | 3,9583 | 4,1250 |

| N | 18 | 24 | 25 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 24 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.383 | 1,09014 | 0.89815 | 1,33278 | 1,17422 | 0.96309 | 0.93153 | 1,05763 | 0.99909 | 0.99181 | |

| 2–6 years | Mean | 4,77 | 4,2564 | 4,5750 | 4,2286 | 4,2683 | 4,3000 | 4,4889 | 3,7429 | 4,3721 | 4,3095 |

| N | 43 | 39 | 40 | 35 | 41 | 40 | 45 | 35 | 43 | 42 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.751 | 1,16343 | 0.90263 | 1,11370 | 1,24548 | 1,15913 | 1,10005 | 1,29121 | 0.97647 | 1,02382 | |

| Over 6 years | Mean | 4,23 | 3,7969 | 3,8750 | 3,5833 | 3,7042 | 3,7917 | 3,8784 | 3,7288 | 3,7013 | 3,6533 |

| N | 74 | 64 | 56 | 60 | 71 | 72 | 74 | 59 | 77 | 75 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,360 | 1,40498 | 1,45305 | 1,45313 | 1,54360 | 1,50994 | 1,50754 | 1,49517 | 1,51367 | 1,54652 | |

| Total | Mean | 4,47 | 4,0548 | 4,1690 | 3,8333 | 3,9359 | 4,0516 | 4,1829 | 3,7737 | 3,9636 | 3,9500 |

| N | 150 | 146 | 142 | 132 | 156 | 155 | 164 | 137 | 165 | 160 | |

| Standard deviation | 1,157 | 1,24724 | 1,19081 | 1,33746 | 1,35684 | 1,32309 | 1,29300 | 1,36119 | 1,30146 | 1,31656 |

| Tested Value a,b | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Statistics Used | 1 * | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Kruskal–Wallis’ H | 5,870 | 4,443 | 8,631 | 5,275 | 4,736 | 3,903 | 7,895 | 1,950 | 6,061 | 5,420 |

| Df | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Asymptotic significance | 0.118 | 0.217 | 0.035 | 0.153 | 0.192 | 0.272 | 0.048 | 0.583 | 0.109 | 0.143 |

| Presence of Buddy | Manufacturing Company | Trading Company | Service Company | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Answers | N | % | N | % | N | % | N (%) |

| Yes | 20 | 80 | 17 | 50 | 58 | 48.7 | 95 (53.4) |

| No | 5 | 20 | 17 | 50 | 61 | 51.3 | 83 (46.6) |

| Total | 25 | 100 | 34 | 100 | 119 | 100 | 178 (100) |

| Type of Statistics Used | Value | df | Asymptotic Significance (2-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s chi-squared test | 8,304 | 2 | 0.016 |

| Odds ratio | 8,903 | 2 | 0.012 |

| Linear correlation test | 6,270 | 1 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krugiełka, A.; Bartkowiak, G.; Knap-Stefaniuk, A.; Sowa-Behtane, E.; Dachowski, R. Onboarding in Polish Enterprises in the Perspective of HR Specialists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021512

Krugiełka A, Bartkowiak G, Knap-Stefaniuk A, Sowa-Behtane E, Dachowski R. Onboarding in Polish Enterprises in the Perspective of HR Specialists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021512

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrugiełka, Agnieszka, Grażyna Bartkowiak, Agnieszka Knap-Stefaniuk, Ewa Sowa-Behtane, and Ryszard Dachowski. 2023. "Onboarding in Polish Enterprises in the Perspective of HR Specialists" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021512

APA StyleKrugiełka, A., Bartkowiak, G., Knap-Stefaniuk, A., Sowa-Behtane, E., & Dachowski, R. (2023). Onboarding in Polish Enterprises in the Perspective of HR Specialists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021512