Effect of Midwife-Provided Orientation of Birth Companions on Maternal Anxiety and Coping during Labor: A Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Control Trial in Eastern Uganda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

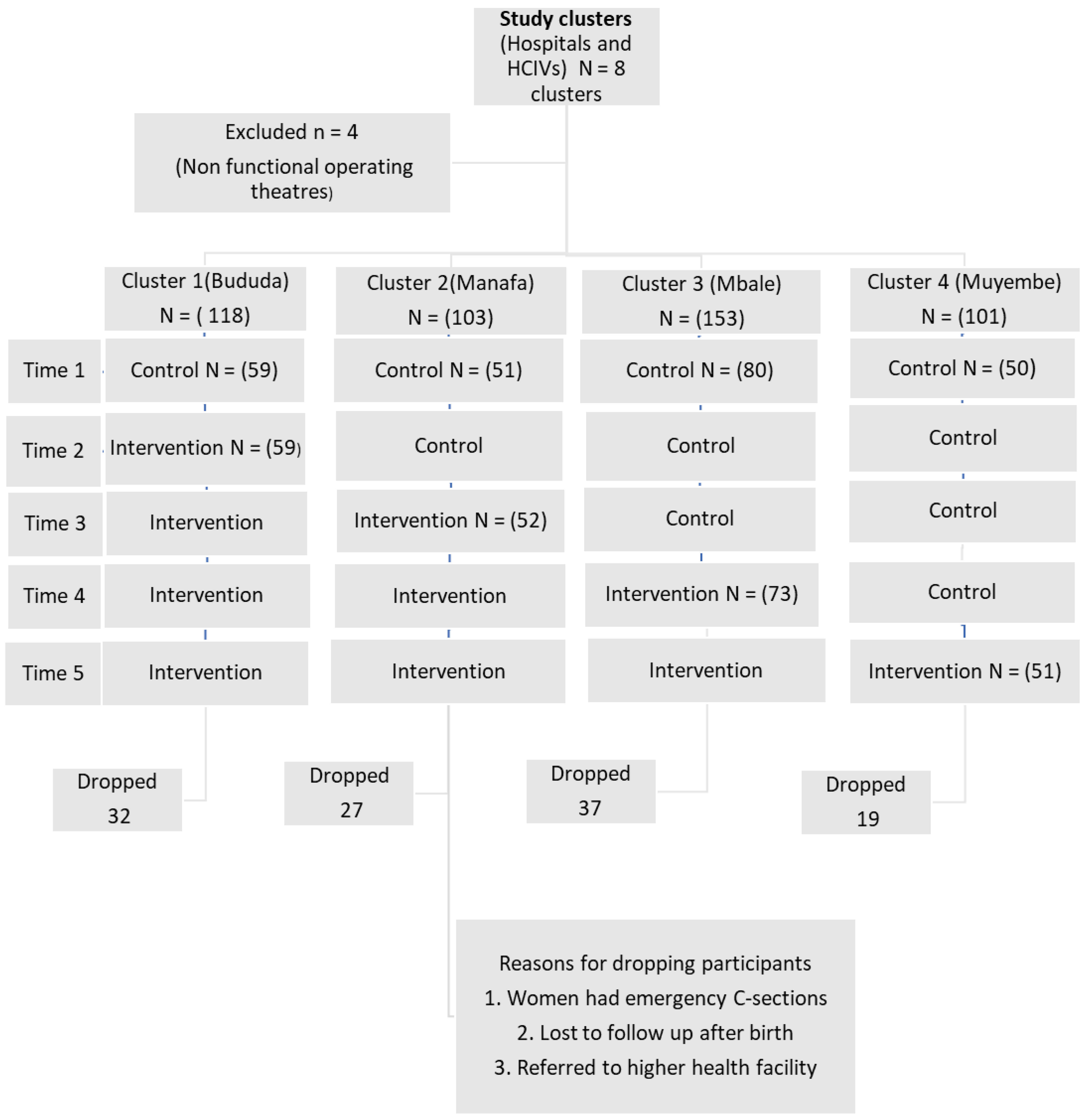

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Sociodemographic and Obstetric Characteristics

3.2. Maternal Anxiety

3.3. Coping with Labor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Das, J.K.; Bahl, R.; Lawn, J.E.; Salam, R.A.; Paul, V.K.; Sankar, M.J.; Blencowe, H.; Rizvi, A.; Chou, V.B. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014, 384, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.F.; Andersson, E. The birth experience and women’s postnatal depression: A systematic review. Midwifery 2016, 39, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.K.; Corwin, E.J. Proposed biological linkages between obesity, stress, and inefficient uterine contractility during labor in humans. Med. Hypotheses 2011, 76, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijahan, R.; Kordi, M. Risk factors of dystocia in nulliparous women. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 39, 254. [Google Scholar]

- Nahaee, J.; Abbas-Alizadeh, F.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S. Pre- and during- labour predictors of dystocia in active phase of labour: A case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.K. The nature of labor pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186 (Suppl. 5), S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Gulliver, B.; Fisher, J.; Cloyes, K.G. The coping with labor algorithm: An alternate pain assessment tool for the laboring woman. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2010, 55, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordăchescu, D.A.; Paica, C.I.; Boca, A.E.; Gică, C.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Peltecu, G.; Veduță, A.; Gică, N. Anxiety, Difficulties, and Coping of Infertile Women. Healthcare 2021, 9, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Simkin, P. Supportive care during labor: A guide for busy nurses. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2002, 31, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakian-Khasholian, T.; Portela, A. Companion of choice at birth: Factors affecting implementation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorstensson, S.; Nissen, E.; Ekström, A. An exploration and description of student midwives’ experiences in offering continuous labour support to women/couples. Midwifery 2008, 24, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyenze, E.W.; Byamugisha, J.K.; Tumwesigye, N.M.; Muwanguzi, P.A.; Nalwadda, G.K. A qualitative exploratory interview study on birth companion support actions for women during childbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Companion of Choice during Labour and Childbirth for Improved Quality of Care: Evidence-to-Action Brief, 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Namaganda, G.; Oketcho, V.; Maniple, E.; Viadro, C. Making the transition to workload-based staffing: Using the Workload Indicators of Staffing Need method in Uganda. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bohren, M.A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C.; Fukuzawa, R.K.; Cuthbert, A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Libr. 2017, 6, CD003766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.A.; Lilford, R.J. The stepped wedge trial design: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials 2010, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Statistics, U. ICF, Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report; Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), UBOS and ICF Kampala: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, L.; Banse, R. Psychological aspects of childbirth: Evidence for a birth-related mindset. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 124–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copas, A.J.; Lewis, J.J.; Thompson, J.A.; Davey, C.; Baio, G.; Hargreaves, J.R. Designing a stepped wedge trial: Three main designs, carry-over effects and randomisation approaches. Trials 2015, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hemming, K.; Girling, A.; Haines, T.; Lilford, R. Protocol: Consort extension to stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014, 363, k1614. [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson, D.J. Contamination in trials: Is cluster randomisation the answer? BMJ 2001, 322, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cook, A.J.; Delong, E.; Murray, D.M.; Vollmer, W.M.; Heagerty, P.J. Statistical lessons learned for designing cluster randomized pragmatic clinical trials from the NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory Biostatistics and Design Core. Clin. Trials 2016, 13, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Facco, E.; Zanette, G.; Bacci, C.; Sivolella, S.; Cavallin, F.; Manani, G. Validation of visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A) in dentistry. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 40, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokyildiz Surucu, S.; Ozturk, M.; Avcibay Vurgec, B.; Alan, S.; Akbas, M. The effect of music on pain and anxiety of women during labour on first time pregnancy: A study from Turkey. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 30, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.; Ip, W.-Y.; Chan, D. Maternal anxiety and feelings of control during labour: A study of Chinese first-time pregnant women. Midwifery 2007, 23, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell-Jones, J.M.; Haasbroek, M.; Van der Westhuizen, J.L.; Dyer, R.A.; Lombard, C.J.; Duys, R.A. Overcoming language barriers using an information video on spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery: Implementation and impact on maternal anxiety. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E.D. An innovation in the assessment of labor pain. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 31, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, E.; Roberts, L.; Zelman, K.; Michelli, S.; Hastings-Tolsma, M. Implementation of Robert’s Coping with Labor Algorithm© in a large tertiary care facility. Midwifery 2017, 50, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, K.; Haines, T.P.; Chilton, P.J.; Girling, A.J.; Lilford, R.J. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: Rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2015, 350, h391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Lagakos, S.W.; Ware, J.H.; Hunter, D.J.; Drazen, J.M. Statistics in medicine—Reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salehi, A.; Fahami, F.; Beigi, M. The effect of presence of trained husbands beside their wives during childbirth on women’s anxiety. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2016, 21, 611. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, W.Y.; Tang, C.S.; Goggins, W.B. An educational intervention to improve women’s ability to cope with childbirth. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munkhondya, B.M.; Munkhondya, T.E.; Chirwa, E.; Wang, H. Efficacy of companion-integrated childbirth preparation for childbirth fear, self-efficacy, and maternal support in primigravid women in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beiranvand, S.P.; Moghadam, Z.B.; Salsali, M.; Majd, H.A.; Birjandi, M.; Khalesi, Z.B. Prevalence of fear of childbirth and its associated factors in primigravid women: A cross-sectional study. Shiraz E Med. J. 2017, 18, e61896. [Google Scholar]

- Rouhe, H.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Halmesmäki, E.; Saisto, T. Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG 2009, 116, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujita Devi, N.; Shinde, P.; Shaikh, G.; Khole, S. Level of anxiety towards childbirth among primigravida and multigravida mothers. IJAR 2018, 4, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli, S.E.; Walsh, D.; Spiby, H. First-time mothers’ expectations of the unknown territory of childbirth: Uncertainties, coping strategies and ‘going with the flow’. Midwifery 2018, 63, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi Najafi, T.; Latifnejad Roudsari, R.; Ebrahimipour, H. The best encouraging persons in labor: A content analysis of Iranian mothers’ experiences of labor support. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orkin, A.M.; Nicoll, G.; Persaud, N.; Pinto, A.D. Reporting of Sociodemographic Variables in Randomized Clinical Trials, 2014–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Heumen, M.A.; Hollander, M.H.; Van Pampus, M.G.; Van Dillen, J.; Stramrood, C.A. Psychosocial predictors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder in women with a traumatic childbirth experience. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soet, J.E.; Brack, G.A.; DiIorio, C. Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth 2003, 30, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Gau, M.-L.; Huang, C.-J.; Cheng, H.-M. Effects of non-pharmacological coping strategies for reducing labor pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohren, M.A.; Berger, B.O.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Tunçalp, Ö. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD012449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olza, I.; Uvnas-Moberg, K.; Ekström-Bergström, A.; Leahy-Warren, P.; Karlsdottir, S.I.; Nieuwenhuijze, M.; Villarmea, S.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Kazmierczak, M.; Spyridou, A. Birth as a neuro-psycho-social event: An integrative model of maternal experiences and their relation to neurohormonal events during childbirth. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvisut, R.; Traisrisilp, K.; Tongsong, T. Efficacy of aromatherapy for reducing pain during labor: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.; Skinner, J.; Foureur, M. The emotional journey of labour—Women’s perspectives of the experience of labour moving towards birth. Midwifery 2014, 30, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | All Participants | Control | Intervention | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 3 | ||||

| 15–24 | 291(61.7%) | 50.8% | 49.2% | 0.721 |

| 25–40 | 181(38.3%) | 49.2% | 50.8% | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 252(53.1%) | 52.4% | 47.6% | 0.544 |

| Secondary | 186(39.2) | 49.5% | 50.5% | |

| Tertiary | 37(7.8%) | 43.2% | 56.8% | |

| Marital status 10 | ||||

| Unmarried | 99(21.3%) | 29.3% | 70.7% | 0.000 |

| Married | 366(78.7%) | 56.3% | 43.7% | |

| Support person 14 | ||||

| Spouse | 155(33.6%) | 60% | 40% | 0.003 |

| Parent | 185(40.1%) | 46.5% | 53.5% | |

| Sibling | 103(22.3%) | 36.9% | 63.1% | |

| Friend | 18(3.9%) | 55.6% | 44.4% | |

| Parity | ||||

| One | 212(44.7%) | 51.9% | 48.1% | 0.684 |

| Two | 109(23%) | 45.9% | 54.1% | |

| Three | 83(17.5%) | 50.6% | 49.4% | |

| Four or more | 70(14.8) | 54.3% | 35.7% | |

| Gestation weeks | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.3 | 38.2 (1.0) | 38.3 (1.0) | 0.277 |

| Cervical dilatation on admision | ||||

| 4 cm | 160(33.7%) | 40% | 60% | 0.001 |

| 5 cm | 113(23.8%) | 50.4% | 49.6% | |

| 6–7 cm | 201(42.4%) | 59.2% | 40.8% | |

| Birthweight Mean | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 0.819 |

| Cluster Bududa | 118 | 50% | 50% | 0.962 |

| Manafwa | 103 | 49.5% | 50.5% | |

| Mbale | 153 | 52.3% | 47.7% | |

| Muyembe | 101 | 49.5% | 50.5% |

| Characteristic | Control Mean (SD) | Intervention Mean (SD) | Diff. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility Mbale Bududa Manafa Muyembe_Sironko | 6.3(2.3) 5.9(1.3) 5.3(1.8) 5.0(1.7) | 3.4(2.2) 6.4(1.3) 5.4(1.4) 5.4(1.3) | 2.9 −0.5 −0.1 −0.4 | 0.704 >0.999 0.077 0.062 |

| Age 3 15–24 25–40 | 5.8(1.9) 5.6(1.9) | 5.1(2.1) 5.2(1.9) | 0.7 0.4 | 0.229 0.999 |

| Education Primary Secondary Above secondary | 5.9(1.9) 5.5(1.9) 5.9(2.2) | 5.1(2.1) 5.2(2.0) 5.4(1.9) | 0.8 0.3 0.5 | 0.565 0.625 0.532 |

| Marital status Unmarried Married | 6.1(1.7) 5.6(1.9) | 5.9(1.8) 4.9(2.0) | 0.2 0.7 | 0.766 0.488 |

| Support person Spouse Parent Sibling Friend/relative | 5.5(1.7) 5.8(1.9) 6.2(2.0) 6.5(1.8) | 5.6(1.5) 5.1(2.1) 4.8(2.3) 5.5(1.8) | −0.1 0.7 1.4 1.0 | 0.331 0.345 0.361 >0.999 |

| Parity One Two Three Four or more | 6.1(2.0) 5.1(1.8) 5.0(1.5) 6.0(2.1) | 5.3(2.2) 5.1(2.0) 4.8(2.0) 4.9(2.0) | 0.8 0.0 0.2 1.1 | 0.329 0.451 0.070 0.787 |

| Cervical dilatation on admission 4 cm 5 cm 6–7 cm | 5.9(2.0) 6.2(2.0) 5.5(1.8) | 5.3(2.1) 5.1(2.0) 5.1(2.1) | 0.6 1.1 0.4 | 0.685 >0.999 0.126 |

| Augmentation No Yes | 5.6(1.9) 6.3(1.9) | 5.1(2.0) 5.1(2.4) | 0.5 1.2 | 0.470 0.217 |

| Coef. | p-Value | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control period Intervention period | −0.62 | 0.001 * | [−1.0–(−)0.2] |

| Age 25 and above | 0.20 | 0.427 | [−0.3–0.7] |

| Parity Two Three Four+ | −0.41 −0.88 −0.32 | 0.103 0.003 0.354 | [−0.9–0.1] [−1.5–(−)0.3] [−1.0–0.4] |

| Cervical dilatation on admission 5 cm 6 cm | −0.14 −0.88 | 0.191 0.003 | [−0.5–0.5] [−0.7–0.2] |

| Support person Parent Sibling Friend/other relatives | −0.16 −0.34 0.50 | 0.479 0.191 0.275 | [−0.6–0.3] [−0.8–0.2] [−0.4–1.5] |

| Control | Intervention | * p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coping at 4–7 cm Not coping Coping | 41 (17.1) 199 (82.9) | 24 (10.3) 210 (89.7) | 0.031 * |

| Coping at 8–10 cm Not coping Coping Not applicable (Had cesarean section) | 110 (45.8) 129 (53.8) 01 (0.4) | 99 (42.3) 134 (57.3) 01 (0.4) | 0.729 |

| Coping 2nd stage Not coping Coping Not applicable (Had ceserean section) | 95 (39.6) 125 (52.1) 20 (8.3) | 83 (35.5%) 125 (53.4) 26 (11.1) | 0.469 |

| Characteristic | Control-Total Number. (Proportion Coping) | Intervention-Total Number. (Proportion Coping) | Diff. | Prtest: p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility Mbale Bududa Manafa Muyembe_Sironko | 80(0.75) 59(0.79) 51(0.94) 50(0.88) | 72(0.96) 59(0.78) 52(0.96) 51(0.88) | 0.21 −0.1 0.02 0.0 | <0.001 * 0.895 0.641 1.000 |

| Age 3 15–24 25–40 | 148(0.81) 89(0.87) | 143(0.89) 92(0.91) | 0.8 0.4 | 0.057 0.389 |

| Education Primary Secondary Above secondary | 132(0.83) 92(0.84) 16(0.81) | 119(0.91) 94(0.89) 21(0.86) | 0.08 0.05 0.05 | 0.062 0.318 0.682 |

| Marital status Unmarried Married | 29(0.76) 206(0.86) | 69(0.86) 160(0.91) | 0.1 0.06 | 0.229 0.083 |

| Support person | ||||

| Spouse | 93(0.84) | 62(0.90) | 0.06 | 0.286 |

| Parent | 86(0.84) | 98(0.89) | 0.05 | 0.320 |

| Sibling | 38(0.84) | 65(0.89) | 0.05 | 0.464 |

| Friend/relative | 10(0.7) | 8(0.88) | 0.18 | 0.360 |

| Parity | ||||

| One | 110(0.79) | 101(0.86) | 0.1 | 0.049 * |

| Two | 50(0.80) | 59(0.92) | 0.12 | 0.068 |

| Three | 42(0.95) | 41(0.93) | 0.02 | 0.701 |

| Four or more | 38(0.84) | 32(0.97) | 0.13 | 0.072 |

| Cervical dilatation on admission 4 cm 5 cm 6–7 cm | 64(0.81) 57(0.77) 119(0.87) | 96(0.90) 56(0.86) 82(0.91) | 0.10 0.22 0.380 | 0.109 0.218 0.379 |

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control period Intervention period | 1.8 [1.1–3.1] | 0.032 * | 1.8 [1.0–3.2] | 0.052 |

| Age 15–24 25+ | 1.4 [0.8–2.5] | 0.206 | 1.0 [0.5–2.3] | 0.905 |

| Parity Two Three Four+ | 1.3 [1.3–2.5] 3.3 [1.3–8.8] 1.9 [0.8–4.5] | 0.387 0.160 0.138 | 1.3 [0.6–2.7] 3.3 [1.1–9.6] 2.3 [0.7–7.2] | 0.460 0.033 0.166 |

| Cervical dilatation on admission 5 cm 6 cm | 0.7 [0.3–1.3] 1.2 [0.6–2.2] | 0.228 0.612 | 0.6 [0.3–1.2] 1.1 [0.5–2.1] | 0.150 0.861 |

| Support person Parent Sibling Friend/other relatives | [0.6–2.0] 1.1 [0.5–2.3] 0.5 [0.2–1.8] | 0.891 0.829 0.328 | 1.1 [0.6–2.3] 1.2 [0.5–2.6] 0.5 [0.1–1.7] | 0.710 0.721 0.249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wanyenze, E.W.; Nalwadda, G.K.; Byamugisha, J.K.; Muwanguzi, P.A.; Tumwesigye, N.M. Effect of Midwife-Provided Orientation of Birth Companions on Maternal Anxiety and Coping during Labor: A Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Control Trial in Eastern Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021549

Wanyenze EW, Nalwadda GK, Byamugisha JK, Muwanguzi PA, Tumwesigye NM. Effect of Midwife-Provided Orientation of Birth Companions on Maternal Anxiety and Coping during Labor: A Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Control Trial in Eastern Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021549

Chicago/Turabian StyleWanyenze, Eva Wodeya, Gorrette K. Nalwadda, Josaphat K. Byamugisha, Patience A. Muwanguzi, and Nazarius Mbona Tumwesigye. 2023. "Effect of Midwife-Provided Orientation of Birth Companions on Maternal Anxiety and Coping during Labor: A Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Control Trial in Eastern Uganda" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021549