Co-Design and Validation of a Family Nursing Educational Intervention in Long-Term Cancer Survivorship Using Expert Judgement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Expert Selection

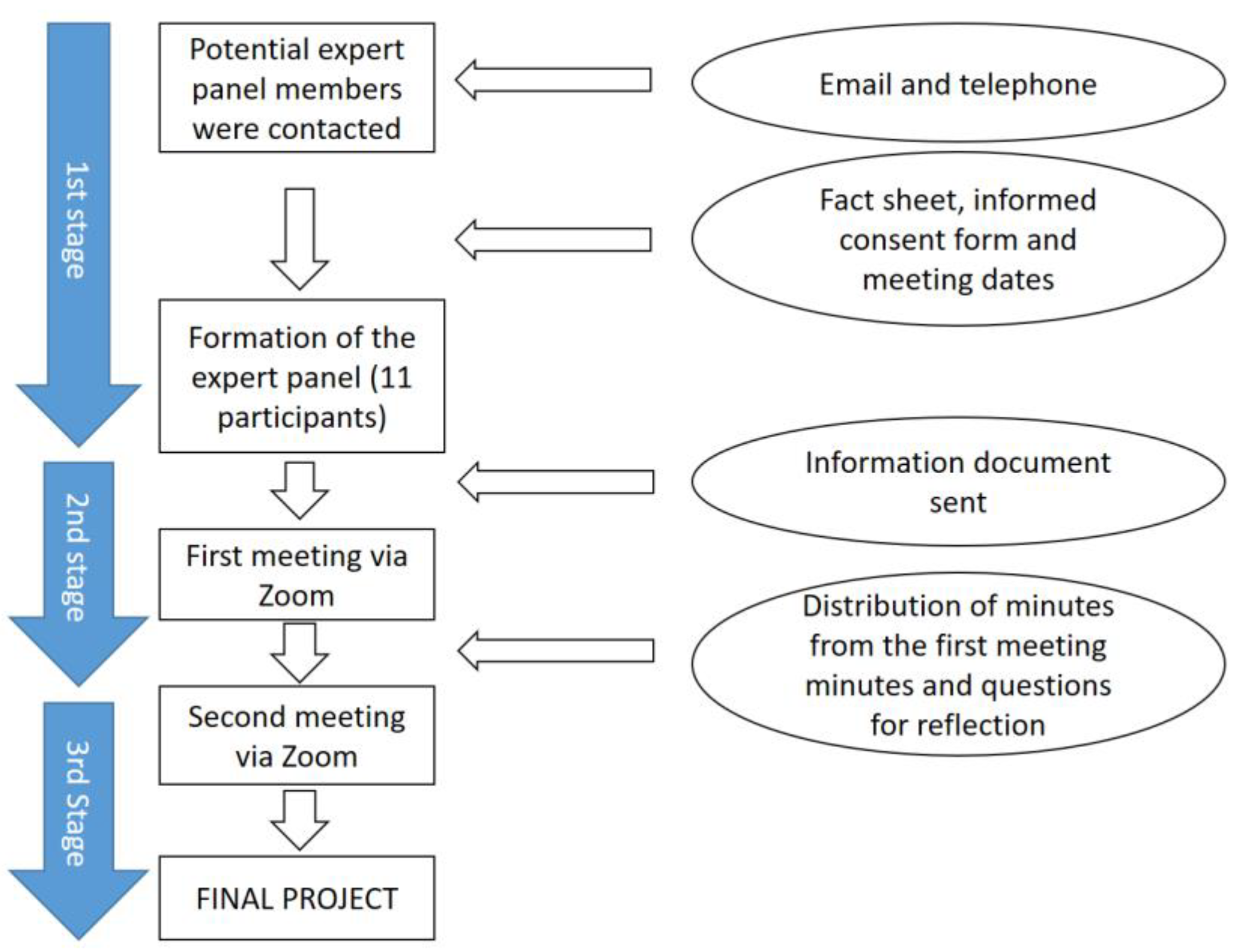

2.2.2. Conducting the Expert Panel

2.2.3. Stage 1. Constitution of the Expert Panel, Final Expert Selection, and Information

2.2.4. Stage 2. First Expert Panel Meeting

2.2.5. Stage 3. Second Expert Panel Meeting: Content Validation of the Intervention, Experts’ Opinion, and Proposed Changes

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Rigor

2.5. Ethics Committee Approval

3. Results

3.1. Experts’ Opinions Regarding the Content in the Educational Intervention

- Understand the needs of long-term cancer survivors and their families.

- Know the characteristics of the family interview according to the Calgary Family Assessment and Intervention Model [27].

- Acquire the ability to conduct a family interview according to the Calgary Model.

- Encourage an attitude of care focused on the cancer survivor and his or her family.

- Encourage interdisciplinary work that promotes family-focused care in cancer survivorship.

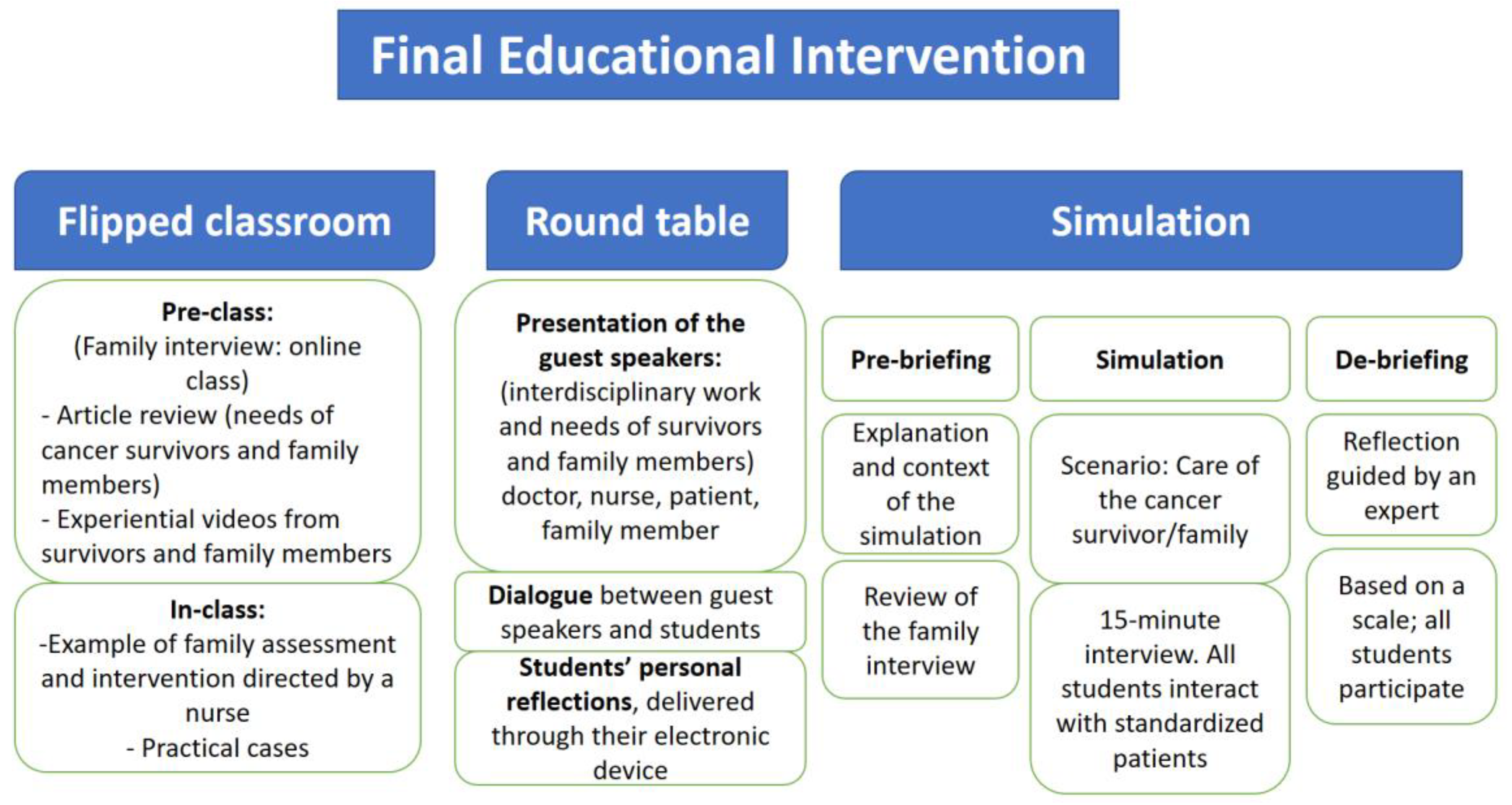

3.2. Combination of Innovative Teaching Methods

3.3. Need of Education in Long-Term Cancer Survivorship

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eloranta, S.; Smedby, K.E.; Dickman, P.W.; Andersson, T.M. Cancer survival statistics for patients and healthcare professionals—A tutorial of real-world data analysis. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 289, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padura Blanco, I.; Ulibarri Ochoa, A. Critical Review of The Literature on The Unmet Need of Cancer Survivors. Enferm. Oncol. 2021, 23, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, P.; Schandl, A.; Aaronson, N.K.; Adami, H.; De Lorenzo, F.; Denis, L.; Faithfull, S.; Liu, L.; Meunier, F.; Ulrich, C. Cancer survivorship: An integral part of Europe ’s research agenda. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.; Brunner, M.; Keep, M.; Hines, M.; Nagarajan, S.V.; Kielly-Carroll, C.; Dennis, S.; McKeough, Z.; Shaw, T. Interdisciplinary eHealth Practice in Cancer Care: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradsen, H.; Brødsgaard, A.; Østergaard, B.; Svavarsdottir, E.; Karin, B.D.; Imhof, L.; Luttik, M.L.; Mahrer-Imhof, R.; García-Vivar, C. Health practices in Europe towards families of older patients with cancer: A scoping review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 35, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallar Oriol, B.; Garcia-Vivar, C. Necesidades de los familiares en la etapa de larga supervivencia de cáncer. The needs of family members in long-term cancer. Enferm. Oncol. 2019, 21, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Padova, S.; Grassi, L.; Vagheggini, A.; Belvederi, M.; Folesani, F.; Rossi, L.; Farolfi, A.; Bertelli, T.; Passardi, A.; Berardi, A.; et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in long-term disease-free cancer survivors and their family caregivers. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 3974–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurocarers and European Cancer Patient Coalition. White Paper on Cancer Carers. Finding the Right Societal Response to Give People with Cancer and Their Carers a Proper Quality of Life. 2017. Available online: https://eurocarers.org/publications/joint-white-paper-on-cancer-carers-with-ecpc/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- RNAO. International Affairs & Best Practice Guidelines. 2015. Available online: www.RNAO.ca/bestpractices (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Homberg, A.; Klafke, N.; Glassen, K.; Loukanova, S.; Mahler, C. Complementary Therapies in Medicine Role competencies in interprofessional undergraduate education in complementary and integrative medicine: A Delphi study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 54, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekema, S.; Luttik, M.L.A.; Steggerda, G.E.; Paans, W.; Roodbol, P.F. Measuring Change in Nurses ’ Perceptions About Family Nursing Competency Following a 6-Day Educational Intervention. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 508–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granek, L.; Mizrakli, Y.; Ariad, S.; Jotkowitz, A.; Geffen, D.B. Impact of a 3-Day Introductory Oncology Course on First-Year International Medical Students. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.; Reguant, M.; Canet, O. Learning outcomes of “The Oncology Patient” study among nursing students: A comparison of teaching strategies. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 46, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiers, S.J.; Eggenberger, S.K.; Krumwiede, N. Development and Implementation of a Family-Focused Undergraduate Nursing Curriculum: Minnesota State University, Mankato. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 307–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggenberger, S.K.; Marita, S. A family nursing educational intervention supports nurses and families in an adult intensive care unit. Aust. Crit. Care 2016, 29, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierwaltes, P.; Clisbee, D.; Tesl, M.A.; Eggenberger, S.K. An Educational Intervention Incorporating Digital Storytelling to Implement Family Nursing Practice in Acute Care Settings. J. Fam. Nurs. 2020, 26, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Alemán, T.; Esandi, N.; Pardavila-Belio, M.I.; Pueyo-Garrigues, M.; Canga-Armayor, N.; Alfaro-Diaz, C.; Canga-Armayor, A. Effectiveness of Educational Programs for Clinical Competence in Family Nursing: A Systematic Review. J. Fam. Nurs. 2021, 27, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtslander, L.; Solar, J.; Smith, N.R. The 15-Minute Family Interview as a Learning Strategy for Senior Undergraduate Nursing Students. J. Fam. Nurs. 2013, 19, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros, B.; Durall, E. Challenges and opportunities of participatory design in educational technology. Edutec. Rev. Electrón. Tecnol Educ. 2020, 74, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonal Ruiz, R.; Marzán Delis, M.; González García, R. Some consensus methods in medical education research. In Proceedings of the VIII Jornada Científica de la SOCECS. Sociedad Cubana de Educadores en Ciencias de la Salud de Holguin, Holguin, Cuba, 19–21 December 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Llorente, C. La aplicación del juicio de experto como técnica de evaluación de las tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TIC). Rev. Tecnol. Inf. Comun. Educ. 2013, 7, 11–22. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260750592 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Robles Garrote, P.; del Rojas, M.C. Validation by expert judgements: Two cases of qualitative research in Applied Linguistics. Rev. Nebrija Linguist. Apl. 2015, 18, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Pérez, J.; Cuervo-Martínez, Á. Validez De Contenido Y Juicio De Expertos: Una Aproximación a Su Utilización. Av. Medición 2008, 6, 27–36. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302438451 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Lecours, A. Scientific, professional and experiential validation of the model of preventive behaviours at work: Protocol of a modified Delphi Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa (accessed on 1 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; McCabe, C.; Keogh, B.; Brady, A.; McCann, M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Leahey, M. Nurses & Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention, 6th ed.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson Smith, K.; Cunningham, K.B.; Cecil, J.E.; Laidlaw, A.; Cairns, P.; Scanlan, G.M.; Tooman, T.R.; Aitken, G.; Ferguson, J.; Gordon, L.; et al. Supporting doctors’ well-being and resilience during COVID-19: A framework for rapid and rigorous intervention development. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2022, 14, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey-Murto, S.; Varpio, L.; Wood, T.J.; Gonsalves, C.; Ufholz, L.A.; Mascioli, K.; Wang, C.; Foth, T. The Use of the Delphi and Other Consensus Group Methods in Medical Education Research: A Review. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D.; Anstey, S.; Kelly, D.; Hopkinson, J. An innovation in curriculum content and delivery of cancer education within undergraduate nurse training in the UK. What impact does this have on the knowledge, attitudes and confidence in delivering cancer care? Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemp, J.R.; Frazier, L.M.; Glennon, C.; Trunecek, J.; Irwin, M. Improving Cancer Survivorship Care: Oncology Nurses’ Educational Needs and Preferred Methods of Learning. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietmann, M.E. Nurse Faculty Beliefs and Teaching Practices for the Care of the Cancer Survivor in Undergraduate Nursing Curricula. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinnesen, M.S.; Olszewski, A.; Breit-Smith, A.; Guo, Y. Collaborating with an Expert Panel to Establish the Content Validity of an Intervention for Preschoolers with Language Impairment. Commun. Disord. Q. 2020, 41, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.A.; Goedde, M.; Bertsch, T.; Beatty, D. Advancing the Future of Patient Safety in Oncology: Implications of Patient Safety Education on Cancer Care Delivery. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Osle, M.; La Rosa-Salas, V.; Ambrosio, L.; Elizondo-Rodriguez, N.; Garcia-Vivar, C. Educational methods used in cancer training for health sciences students: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 97, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Specialists in the area of oncology. | Professionals with less than 10 years of experience (because of their short professional trajectory in this area). |

| Currently working with cancer survivors and their families. | Relatives and survivors with less than 5 years free of disease (as they are not considered to be long-term cancer survivors). |

| Teaching experience in the area of health sciences. | Early career nursing students. |

| Cancer survivors who have been untreated for at least 5 years. | |

| Family members of cancer survivors who have been untreated for at least 5 years. | |

| Cancer survivors and families with sufficient academic training to actively participate in the project and in the expert panel. | |

| Being able to complete the two meetings via Zoom. | |

| Senior nursing students. |

| Expert | Areas of Knowledge | Main Role | Years of Professional Experience/Years of Survivorship |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nursing | Primary care nurse * | Over 20 years |

| 2. | Nursing | Hospital nurse ** | Over 10 years |

| 3. | Nursing | University professor of nursing ** | Over 10 years |

| 4. | Nursing | University professor of nursing *** | Over 15 years |

| 5. | Nursing | University professor of nursing ** | Over 20 years |

| 6. | Medicine | Radiation oncologist **** | Over 15 years |

| 7. | Pharmacy | Oncology pharmacist | Over 10 years |

| 8. | Psychology | Psycho-oncologist | Over 10 years |

| 9. | Patient | Breast cancer survivor | 10 years |

| 10. | Family member | Daughter of a colon cancer survivor | 15 years |

| 11. | Senior student | Four-year university nursing student | 4 years |

| Declaration | Category | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| “It is key to make good use of the simulation to learn how to do a family interview, for this the previous readings are important. Provide students with articles about the 15-minute Calgary Model interview” (Nurse researcher). | Training contents | Opinions of the experts on the content of the educational intervention |

| “The contents have to be dynamic, clear and brief and that they are delivered to the students through videos, TEDx conferences and research articles” (Nurse teacher). | ||

| “It is necessary to know the needs and experiences of cancer survivors and their families” (All experts). | ||

| “It seems important to me to address interdisciplinary work in a round table and how it affects the care of survivors and their families” (Oncologist). | Need for interdisciplinary work | |

| “At the end of the round table, before leaving the classroom, students can answer some questions with their phone or electronic device to encourage them to reflect on what they have heard, mainly about interdisciplinary work” (Oncologist). | ||

| “Patients and family members are afraid of recurrence. For this reason, it is necessary that this concept is present in the intervention and the students learn to give patients and family members a realistic hope” (Psycho-oncologist). | Knowledge of fear of recurrence | |

| “The educational intervention is very well designed, it is very completeand contributes to the acquisition of skills to care for cancer survivors and their families” (Psycho-oncologist). | Good design and varied to acquire competence | Combination of innovative teaching methods |

| “I really liked the intervention. I think it covers everything we need to acquire full competence. I am interested in having different activities and methods because I believe that each one contributes something different” (Student). | ||

| “I recommend the flipped classroom, for the acquisition of knowledge, it allows students to be leaders of their learning, it facilitates clinical reasoning and critical thinking” (Oncologist). “In addition, I propose that the flipped classroom be taught by a clinical nurse with knowledge of the family interview” (Primary care nurse). | Student-led educational methods | |

| “Simulation is something that we students like a lot because it gives us the opportunity to practice before going to the clinical practice” (Student). | ||

| “It is good to allocate a long time to the round table to facilitate the students’ questions to the presenters” (Nurse research). | Dialogue to foster learning | |

| “We consider that the direct participation of survivors and family members in nursing training is a positive factor” (Survivor and family). | ||

| “Training is very necessary, it is very positive for the quality of life of cancer survivors. That nursing is present both in the cancer survivor stage and during treatment” (Cancer survivor). | Need for training to improve quality of life | Need for training in long cancer survival |

| “I consider training important, not only for the survivor and their family, but also because of the economic repercussions that this has for society due to the frequency of sick leave or even partial disability that this situation can cause, which perhaps, with emergency care nursing, could be reduced” (Survivor). | ||

| “It is necessary to train nursing professionals in the care of cancer survivors and their families to be able to carry out a follow-up similar to that carried out during the active phase of cancer treatment” (Oncologist,). | Need for training to improve accompaniment | |

| “Now… where is the nurse who takes care of my dad? Training is needed in this field. I clearly see the need for training in the area of cancer survivorship. No one has cared about me as a relative” (Family member of cancer survivor). | ||

| “In my undergraduate training, I still need to know more about cancer survivorship and family-focused care. It is discussed in class, but I have not had the opportunity to learn it in practice” (in a clinical simulation) (Student). | Need for training in the absence of undergraduate studies | |

| “There is a need for trained nurses who open doors to survivors and their families and introduce them to the system, help them navigate the process, and anticipate the needs of both survivors and family members. The existence of a gap in training in cancer survivorship and family nursing has been well established” (Nurse professor). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domingo-Osle, M.; La Rosa-Salas, V.; Ulibarri-Ochoa, A.; Domenech-Climent, N.; Arbea Moreno, L.; Garcia-Vivar, C. Co-Design and Validation of a Family Nursing Educational Intervention in Long-Term Cancer Survivorship Using Expert Judgement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021571

Domingo-Osle M, La Rosa-Salas V, Ulibarri-Ochoa A, Domenech-Climent N, Arbea Moreno L, Garcia-Vivar C. Co-Design and Validation of a Family Nursing Educational Intervention in Long-Term Cancer Survivorship Using Expert Judgement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021571

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomingo-Osle, Marta, Virginia La Rosa-Salas, Ainhoa Ulibarri-Ochoa, Nuria Domenech-Climent, Leire Arbea Moreno, and Cristina Garcia-Vivar. 2023. "Co-Design and Validation of a Family Nursing Educational Intervention in Long-Term Cancer Survivorship Using Expert Judgement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021571

APA StyleDomingo-Osle, M., La Rosa-Salas, V., Ulibarri-Ochoa, A., Domenech-Climent, N., Arbea Moreno, L., & Garcia-Vivar, C. (2023). Co-Design and Validation of a Family Nursing Educational Intervention in Long-Term Cancer Survivorship Using Expert Judgement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021571