Geopolitical Risk Evolution and Obstacle Factors of Countries along the Belt and Road and Its Types Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods and Data Sources

2.1. Indicator System

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Entropy Weight TOPSIS Method

- (1)

- Index standardization. In order to eliminate the limitation of indicator dimension, we use the range standardization method to nondimensionalize the indicators in different positive and negative directions and obtain the standardized matrix xij:where xij is the standardized value, i represents the i-th country and j represents the j-th evaluation object. i and j are integers and 1 ≤ i ≤ 74, 1 ≤ j ≤ 13. m is the number of countries and n is the number of evaluation objects.

- (2)

- Determine the index weights. Calculate the weight values among the index data using the entropy weight method:

- (3)

- Calculate the optimal solution set and the inferior solution set:where X+ is the optimal solution of the j-th evaluation object, indicating that the country geopolitical risk is at the highest value. X− is the inferior solution of the j-th evaluation object, indicating that the country geopolitical risk is at the lowest value.

- (4)

- Calculate the distance between the geopolitical risk of a single country and the optimal solution set and the inferior solution set:where Di+ is the closeness of the i-th country to the optimal solution. The smaller the Di+, the closer the geopolitical risk of country i is to the optimal solution, and the higher the geopolitical risk of country i is. Di− is the closeness of the i-th country to the inferior solution. The smaller the Di−, the closer the geopolitical risk of country i is to the inferior solution, and the lower the geopolitical risk of country i is.

- (5)

- Calculate the relative closeness of geopolitical risks in a single country:where Ci is the geopolitical risk level of the i-th country, 0 ≤ Ci ≤ 1. The greater the Ci, the closer the geopolitical risk of country i is to the optimal solution, and the higher the geopolitical risk of country i. In order to facilitate comparison, this study refers to relevant studies and classifies the geopolitical risks of countries along the Belt and Road into five levels [46]. When 0.00 < Ci ≤ 0.192, it is a very low risk level; when 0.192 < Ci ≤ 0.365, it is a low risk level; when 0.365 < Ci ≤ 0.455, it is a medium risk level; when 0.455 < Ci ≤ 0.652, it is a high risk level; when 0.652 < Ci ≤ 1, it is a very high risk level.

2.2.2. Obstacle Degree Model

- (1)

- Calculate the gap between individual risk factors and the theoretical maximum value of the risk factor:where Oij is the gap between individual risk factors and the theoretical maximum value of the risk factor, and xij is the standardized value of the risk indicator.

- (2)

- Calculate the effect of individual risk factors on the geopolitical risk of each country:where Ij is the obstacle degree of risk factor j and wj is the weight of risk factor j. The larger the obstacle degree Ij, the stronger the effect of risk factor j on geopolitical risk.

2.2.3. Minimum Variance Method

- (1)

- Calculate the effect of each subsystem on geopolitical risk:where Uz is the obstacle degree of subsystem z, z is an integer and 1 ≤ z ≤ 3.

- (2)

- Calculate the closeness between the geopolitical risk of each country and the theoretical distribution types of geopolitical risk:where Sz2 is the variance, Uz is the effect of subsystem z on geopolitical risk and is the effect of subsystem z on geopolitical risk in theoretical distribution types. As the geopolitical risk system in this study is composed of sovereign risk, military risk and major power intervention, theoretically, there are single system risks, double system risks and three system risks in this study. In theory, the risk value of one subsystem accounting for 100% of the total geopolitical risk is the “single system risks”, the risk value of two subsystems accounting for 50% of the total geopolitical risk is the “double system risks” and the risk value of three subsystems accounting for 33.3% of the total geopolitical risk is the “three system risks”. According to the minimum variance theory [48], compare the variance Sz2 value of country i when is 100%, 50% and 33.3%, and the geopolitical risk type of corresponding to the minimum value of Sz2 is the geopolitical risk type of country i.

2.3. Data Sources

3. Evolution of Geopolitical Risk in Countries along the Belt and Road

3.1. Temporal Evolution of Geopolitical Risk in Countries along the Belt and Road

3.2. Spatial Evolution of Geopolitical Risk in Countries along the Belt and Road

4. Analysis of Geopolitical Risk Obstacle Factors in Countries along the Belt and Road

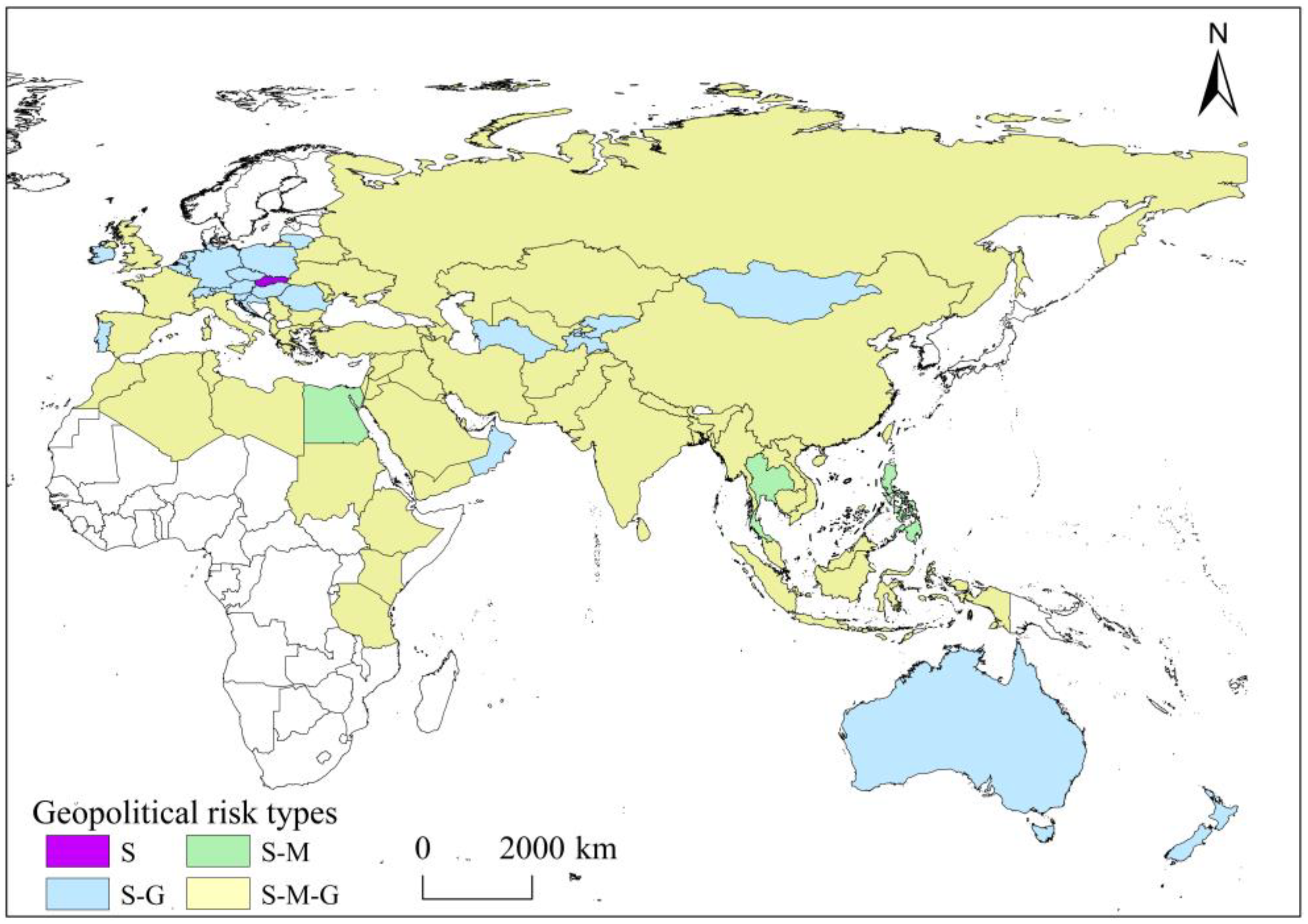

5. Classification of Geopolitical Risk Types in Countries along the Belt and Road

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, W.D.; Dunford, M.; Gao, B.Y. A discursive construction of the Belt and Road Initiative: From neo-liberal to inclusive globalization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.T. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Perspectives from India. China. World. Econ. 2017, 25, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, N. China’s "Belt and Road Initiative": Underwhelming or game-changer? Wash. Q. 2017, 40, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanwani, S. Belt and Road Initiative: Responses from Japan and India—Bilateralism, Multilateralism and Collaborations. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, J.M.F.; Flint, C. The geopolitics of China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative. Geopolitics 2017, 22, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.H.; Hong, Y.R. Can geopolitical risks excite Germany economic policy uncertainty: Rethinking in the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, U.; Ramzan, M.; Shah, M.I.; Doğan, B.; Ajmi, A.N. Analyzing the Nexus Between Geopolitical Risk, Policy Uncertainty, and Tourist Arrivals: Evidence from the United States. Eval. Rev. 2022, 46, 266–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suder, G. Corporate Strategies under International Terrorism and Adversity; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Geopolitical risk trends and crude oil price predictability. Energy 2022, 258, 124824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhong, R.; Sohail, S.; Majeed, M.T.; Ullah, S. Geopolitical risks, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in BRICS: An asymmetric analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 39668–39679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Tian, G.Y.; Wu, Y.Q.; Mo, B. Impacts of geopolitical risks and economic policy uncertainty on Chinese tourism-isted company stock. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 27, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiik, L. Nationalism and anti-ethno-politics: Why ‘Chinese development’ failed at Myanmar’s Myitsone dam. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2016, 57, 307–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.J.; Chiu, C.-W. How important are global geopolitical risks to emerging countries? Int. Econ. 2018, 156, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, L. Western ostracism and China’s presence in Africa. China Inf. 2011, 25, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, D.F.; Collins, K.N.; Ben, G.M. Conflict over sacred space: The case of Nazareth. Cities 2014, 41, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, A.; Peng, P. Geopolitical risk and stock market volatility in emerging economies: Evidence from GARCH-MIDAS model. Discrete. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 1159358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, K.; Klenk, N.L.; Mendez, F. The geopolitics of climate knowledge mobilization: Transdisciplinary research at the science–policy interface(s) in the Americas. Science 2018, 43, 759–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. Changes in US security and defense strategy toward China: Assessment and policy implications. Korean J. Def. Anal. 2021, 32, 539–560. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Ge, Y.; Hu, Z.; Ye, S.; Yang, F.; Jiang, H.; Hou, K.; Deng, Y. Geo-Economic Linkages between China and the Countries along the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road and Their Types. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2022, 19, 12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.; Uddin, G.S.; Suleman, M.T.; Kang, S.H. Geopolitical risk, uncertainty and Bitcoin investment. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 540, 123107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hamori, S. A connectedness analysis among BRICS’s geopolitical risks and the US macroeconomy. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saâdaoui, F.; Ben Jabeur, S.; Goodell, J.W. Causality of geopolitical risk on food prices: Considering the Russo–Ukrainian conflict. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bouri, E.; Klein, T.; Jalkh, N. Geopolitical risk and the returns and volatility of global defense companies: A new race to arms? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.-T.; Tran, T.P. Does geopolitical risk matter for corporate investment? Evidence from emerging countries in Asia. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2021, 62, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepni, O.; Emirmahmutoglu, F.; Guney, I.E.; Yilmaz, M.H. Do the carry trades respond to geopolitical risks? Evidence from BRICS countries. Econ. Syst. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Comprehensive assessment of geopolitical risk in the Himalayan region based on the grid scale. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiyoun, A.N.; Hyunwoo, R.O.H. Measuring North Korean geopolitical risks: Implications for Asia’s financial volatilities. East Asian Policy 2018, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzic, A.; Riad, A.; Tanasiewicz, M.; Attia, S. The increasing population movements in the 21st Century: A call for the E-register of health-related data integrating health care systems in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costola, M.; Donadelli, M.; Gerotto, L.; Gufler, I. Global risks, the macroeconomy, and asset prices. Empir. Econ. 2022, 63, 2357–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, B.; Hatice, O.B.; Mudassar, H.; Russell, G.A. Geopolitical risk spillovers and its determinants. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2022, 68, 463–500. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. Prospects and Challenges on China’s "One Belt, One Road": A Risk Assessment Report; The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh. Political Risk Map 2018: Tensions and Turbulence Ahead; Marsh & McLennan Companies: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; He, Z.; Yang, Y. Energy geopolitics in Central Asia: China’s involvement and responses. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1871–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Chinese Capitalism and the Maritime Silk Road: A world-systems perspective. Geopolitics 2017, 22, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.J. The Belt and Road Initiative and China’s foreign policy toward its territorial and boundary disputes. China. Q. Int. Strateg. Stud. 2015, 1, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataka, H. Geopolitics or Geobody Politics? Understanding the Rise of China and Its Actions in the South China Sea. Asian J. Peacebuild. 2016, 4, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiao, C.; Liu, H. Spatial big data analysis of political risks along the Belt and Road. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Li, J.P. How does geopolitical uncertainty affect Chinese overseas investment in the energy sector? Evidence from the South China Sea Dispute. Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.F.; Xue, L.; Sayer, J.; Riggs, R.A.; Langston, J.D.; Boedhihartono, A.K. Challenges faced by Chinese firms implementing the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’: Evidence from three railway project. Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, C.; Zhu, C.P. The geopolitics of connectivity, cooperation, and hegemonic competition: The Belt and Road Initiative. Geoforum 2019, 99, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. The rise and decline of great powers: The American case. Politics 1988, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkink, G. When geopolitics and religion fuse: A historical perspective. Geopolitics 2006, 11, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.L.; Martek, I. Political risk analysis of foreign direct investment into the energy sector of developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 302, 127023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, F.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Geopolitical risk and oil volatility: A new insight. Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M. The naming of ‘terrorism’ and evil ‘outlaws’: Geopolitical place-making after 11 September. Geopolitics 2003, 8, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, C.; Cai, G.; Zhan, J. Assessment of provincial waterlogging risk based on entropy weight TOPSIS–PCA method. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 1545–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.R.; Zhu, Q.K.; Sun, Y.Y. Regional ecological security and diagnosis of obstacle factors in underdeveloped regions: A case study in Yunnan province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, A.; Rastätter, L. Minimum variance analysis-based propagation of the solar wind observations: Application to real-time global magnetohydrodynamic simulations. Space Weather 2009, 7, S12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.B. Geopolitical encounters and entanglements along the Belt and Road Initiative. Geogr. Compass 2021, 15, e12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenopoulos, S.N.; Agioutantis, Z. Geopolitical risk assessment of countries with rare earth element deposits. Min. Met. Explor. 2019, 37, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.M.; Hu, S.L.; Fang, K.; He, G.Q.; Ma, H.T.; Cui, X.G. A comprehensive assessment of political, economic and social risks and their prevention for the countries along the Belt and Road. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 2966–2984. [Google Scholar]

| Target Layer | Element Layer | Indicator Layer | Indicator Name | Indicator Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geopolitical risk in countries along the Belt and Road | Sovereign risk (S) | Political Risk | Political stability(A1) | − |

| Economic Risk | Investment dependence degree (A2) | + | ||

| Foreign trade dependence degree(A3) | + | |||

| Energy Risk | Energy dependence degree (A4) | + | ||

| Ethnoreligious risk | Ethnic conflict intensity (A5) | + | ||

| Religious conflict intensity (A6) | + | |||

| Military risk (M) | Military coup risk | Military intervention in politics intensity (A7) | + | |

| Violent armed threats | Violent armed threat intensity (A8) | + | ||

| Terrorism Threat | Global terrorism index (A9) | + | ||

| Major power intervention (G) | External Conflict | External conflict intensity (A10) | + | |

| Alliances | Close relations with the United States (A11) | + | ||

| Foreign debt burden | Foreign debt stock as a percentage of GNI(A12) | + | ||

| Aid dependence | Net official development assistance received as a percentage of GNI (A13) | + |

| Country | 2005 | Rank | 2009 | Rank | 2013 | Rank | 2016 | Rank | 2020 | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 0.690 | 2 | 0.631 | 1 | 0.642 | 2 | 0.640 | 2 | 0.666 | 2 |

| Iraq | 0.765 | 1 | 0.602 | 2 | 0.645 | 1 | 0.620 | 3 | 0.653 | 3 |

| Sudan | 0.607 | 3 | 0.573 | 3 | 0.627 | 3 | 0.600 | 4 | 0.551 | 8 |

| Syria | 0.468 | 12 | 0.457 | 11 | 0.610 | 4 | 0.669 | 1 | 0.675 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 0.524 | 6 | 0.509 | 4 | 0.545 | 5 | 0.545 | 5 | 0.603 | 5 |

| Ethiopia | 0.523 | 7 | 0.486 | 6 | 0.528 | 6 | 0.527 | 6 | 0.544 | 9 |

| Myanmar | 0.528 | 5 | 0.462 | 9 | 0.498 | 10 | 0.488 | 8 | 0.614 | 4 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.533 | 4 | 0.505 | 5 | 0.511 | 9 | 0.437 | 18 | 0.537 | 10 |

| Iran | 0.475 | 11 | 0.473 | 7 | 0.516 | 7 | 0.462 | 12 | 0.568 | 6 |

| Lebanon | 0.460 | 13 | 0.461 | 10 | 0.512 | 8 | 0.480 | 9 | 0.522 | 12 |

| Bangladesh | 0.501 | 9 | 0.457 | 12 | 0.473 | 12 | 0.458 | 13 | 0.487 | 17 |

| Nepal | 0.484 | 10 | 0.439 | 13 | 0.469 | 15 | 0.446 | 17 | 0.506 | 14 |

| Yemen | 0.382 | 25 | 0.382 | 23 | 0.461 | 16 | 0.519 | 7 | 0.560 | 7 |

| Indonesia | 0.520 | 8 | 0.468 | 8 | 0.473 | 13 | 0.417 | 22 | 0.473 | 21 |

| Kenya | 0.432 | 17 | 0.421 | 14 | 0.478 | 11 | 0.456 | 14 | 0.524 | 11 |

| Russia | 0.435 | 16 | 0.411 | 17 | 0.453 | 17 | 0.473 | 10 | 0.513 | 13 |

| Algeria | 0.437 | 15 | 0.414 | 15 | 0.446 | 18 | 0.420 | 21 | 0.487 | 18 |

| Libya | 0.367 | 27 | 0.335 | 34 | 0.471 | 14 | 0.471 | 11 | 0.501 | 16 |

| Israel | 0.438 | 14 | 0.413 | 16 | 0.419 | 26 | 0.410 | 25 | 0.442 | 28 |

| Thailand | 0.338 | 33 | 0.393 | 21 | 0.440 | 19 | 0.449 | 16 | 0.444 | 27 |

| India | 0.398 | 21 | 0.399 | 19 | 0.433 | 21 | 0.413 | 24 | 0.466 | 22 |

| Cambodia | 0.402 | 20 | 0.395 | 20 | 0.427 | 22 | 0.406 | 26 | 0.461 | 24 |

| Laos | 0.416 | 18 | 0.401 | 18 | 0.424 | 24 | 0.371 | 32 | 0.411 | 32 |

| Tanzania | 0.408 | 19 | 0.367 | 28 | 0.422 | 25 | 0.402 | 29 | 0.484 | 19 |

| Turkey | 0.320 | 40 | 0.376 | 24 | 0.426 | 23 | 0.435 | 19 | 0.458 | 25 |

| Tajikistan | 0.396 | 22 | 0.370 | 27 | 0.409 | 28 | 0.405 | 27 | 0.475 | 20 |

| Tunisia | 0.351 | 31 | 0.339 | 33 | 0.409 | 29 | 0.416 | 23 | 0.504 | 15 |

| Egypt | 0.334 | 35 | 0.298 | 43 | 0.434 | 20 | 0.432 | 20 | 0.466 | 23 |

| Belarus | 0.366 | 28 | 0.371 | 26 | 0.412 | 27 | 0.363 | 34 | 0.411 | 31 |

| Moldova | 0.381 | 26 | 0.391 | 22 | 0.389 | 32 | 0.372 | 31 | 0.410 | 33 |

| Philippines | 0.345 | 32 | 0.345 | 32 | 0.393 | 31 | 0.392 | 30 | 0.433 | 29 |

| China | 0.331 | 37 | 0.363 | 29 | 0.403 | 30 | 0.404 | 28 | 0.415 | 30 |

| Serbia | 0.385 | 24 | 0.372 | 25 | 0.385 | 33 | 0.359 | 35 | 0.402 | 34 |

| Ukraine | 0.320 | 41 | 0.315 | 39 | 0.352 | 36 | 0.455 | 15 | 0.456 | 26 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.361 | 30 | 0.333 | 35 | 0.362 | 34 | 0.369 | 33 | 0.398 | 35 |

| Vietnam | 0.390 | 23 | 0.362 | 30 | 0.332 | 40 | 0.321 | 40 | 0.374 | 37 |

| Azerbaijan | 0.335 | 34 | 0.327 | 36 | 0.361 | 35 | 0.358 | 36 | 0.388 | 36 |

| Turkmenistan | 0.333 | 36 | 0.316 | 38 | 0.338 | 38 | 0.332 | 38 | 0.368 | 39 |

| Armenia | 0.319 | 42 | 0.311 | 40 | 0.332 | 39 | 0.344 | 37 | 0.363 | 40 |

| Uzbekistan | 0.363 | 29 | 0.324 | 37 | 0.328 | 42 | 0.318 | 41 | 0.318 | 47 |

| Ireland | 0.263 | 54 | 0.349 | 31 | 0.345 | 37 | 0.313 | 43 | 0.304 | 48 |

| Morocco | 0.324 | 39 | 0.294 | 44 | 0.330 | 41 | 0.294 | 46 | 0.349 | 41 |

| Austria | 0.306 | 44 | 0.309 | 41 | 0.315 | 45 | 0.306 | 44 | 0.369 | 38 |

| Mongolia | 0.325 | 38 | 0.306 | 42 | 0.324 | 44 | 0.314 | 42 | 0.290 | 51 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.316 | 43 | 0.275 | 46 | 0.285 | 46 | 0.326 | 39 | 0.335 | 42 |

| Malaysia | 0.303 | 45 | 0.289 | 45 | 0.327 | 43 | 0.284 | 48 | 0.320 | 46 |

| Qatar | 0.294 | 47 | 0.267 | 49 | 0.283 | 47 | 0.272 | 49 | 0.329 | 44 |

| France | 0.272 | 52 | 0.241 | 53 | 0.268 | 50 | 0.304 | 45 | 0.328 | 45 |

| Singapore | 0.295 | 46 | 0.270 | 48 | 0.279 | 48 | 0.259 | 53 | 0.293 | 49 |

| Oman | 0.268 | 53 | 0.254 | 51 | 0.277 | 49 | 0.258 | 54 | 0.291 | 50 |

| Jordan | 0.280 | 49 | 0.223 | 55 | 0.258 | 52 | 0.286 | 47 | 0.334 | 43 |

| United Kingdom | 0.286 | 48 | 0.271 | 47 | 0.258 | 51 | 0.249 | 56 | 0.288 | 52 |

| Netherlands | 0.250 | 56 | 0.252 | 52 | 0.243 | 55 | 0.260 | 51 | 0.261 | 56 |

| Spain | 0.277 | 50 | 0.256 | 50 | 0.220 | 58 | 0.201 | 59 | 0.258 | 58 |

| Kazakhstan | 0.273 | 51 | 0.211 | 56 | 0.257 | 53 | 0.257 | 55 | 0.275 | 54 |

| Greece | 0.192 | 61 | 0.239 | 54 | 0.247 | 54 | 0.235 | 57 | 0.284 | 53 |

| Kuwait | 0.260 | 55 | 0.197 | 58 | 0.221 | 57 | 0.268 | 50 | 0.245 | 59 |

| Belgium | 0.216 | 58 | 0.207 | 57 | 0.208 | 59 | 0.259 | 52 | 0.271 | 55 |

| Bulgaria | 0.207 | 59 | 0.195 | 59 | 0.224 | 56 | 0.195 | 60 | 0.200 | 65 |

| Albania | 0.224 | 57 | 0.181 | 60 | 0.187 | 62 | 0.175 | 66 | 0.206 | 64 |

| Germany | 0.174 | 65 | 0.166 | 64 | 0.165 | 67 | 0.225 | 58 | 0.260 | 57 |

| Slovakia | 0.185 | 62 | 0.178 | 61 | 0.189 | 60 | 0.189 | 61 | 0.209 | 63 |

| Romania | 0.181 | 63 | 0.178 | 62 | 0.188 | 61 | 0.175 | 65 | 0.199 | 66 |

| Switzerland | 0.164 | 66 | 0.169 | 63 | 0.187 | 63 | 0.181 | 62 | 0.230 | 61 |

| Croatia | 0.201 | 60 | 0.165 | 65 | 0.173 | 65 | 0.176 | 64 | 0.193 | 68 |

| Italy | 0.175 | 64 | 0.154 | 68 | 0.185 | 64 | 0.177 | 63 | 0.238 | 60 |

| Slovenia | 0.160 | 67 | 0.162 | 67 | 0.166 | 66 | 0.160 | 68 | 0.185 | 69 |

| Hungary | 0.153 | 68 | 0.163 | 66 | 0.165 | 68 | 0.167 | 67 | 0.184 | 70 |

| Lithuania | 0.147 | 70 | 0.147 | 69 | 0.151 | 69 | 0.152 | 70 | 0.194 | 67 |

| Czech Republic | 0.150 | 69 | 0.143 | 71 | 0.144 | 71 | 0.158 | 69 | 0.166 | 72 |

| Portugal | 0.130 | 72 | 0.143 | 70 | 0.151 | 70 | 0.142 | 71 | 0.154 | 73 |

| Poland | 0.130 | 71 | 0.109 | 72 | 0.118 | 72 | 0.125 | 73 | 0.151 | 74 |

| Australia | 0.115 | 73 | 0.106 | 73 | 0.099 | 74 | 0.134 | 72 | 0.174 | 71 |

| New Zealand | 0.105 | 74 | 0.105 | 74 | 0.107 | 73 | 0.108 | 74 | 0.210 | 62 |

| Country | 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | 2016 | 2020 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Thailand | A9 | A3 | A5 | A9 | A6 | A5 | A9 | A7 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 |

| Indonesia | A6 | A9 | A7 | A6 | A7 | A11 | A6 | A5 | A7 | A6 | A7 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A5 |

| Myanmar | A7 | A11 | A9 | A7 | A11 | A10 | A7 | A13 | A11 | A7 | A11 | A8 | A11 | A7 | A9 |

| Philippines | A9 | A6 | A1 | A9 | A1 | A6 | A9 | A8 | A7 | A9 | A8 | A7 | A9 | A8 | A7 |

| Singapore | A12 | A3 | A4 | A12 | A3 | A4 | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A2 |

| Vietnam | A11 | A7 | A8 | A11 | A7 | A3 | A3 | A7 | A11 | A3 | A7 | A11 | A3 | A7 | A11 |

| Malaysia | A3 | A11 | A8 | A3 | A11 | A8 | A3 | A11 | A8 | A3 | A8 | A6 | A3 | A6 | A5 |

| Laos | A13 | A11 | A8 | A13 | A11 | A6 | A11 | A7 | A13 | A7 | A6 | A11 | A7 | A13 | A6 |

| Cambodia | A11 | A13 | A3 | A11 | A13 | A6 | A13 | A11 | A7 | A11 | A7 | A13 | A11 | A7 | A13 |

| Nepal | A9 | A1 | A11 | A9 | A11 | A13 | A11 | A9 | A13 | A11 | A13 | A10 | A11 | A9 | A13 |

| Pakistan | A7 | A6 | A9 | A9 | A7 | A6 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 |

| India | A9 | A6 | A5 | A9 | A6 | A5 | A9 | A6 | A5 | A9 | A6 | A5 | A9 | A6 | A10 |

| Bangladesh | A9 | A11 | A1 | A7 | A11 | A1 | A7 | A9 | A1 | A9 | A7 | A5 | A7 | A5 | A8 |

| Sri Lanka | A9 | A7 | A6 | A9 | A7 | A5 | A7 | A11 | A6 | A11 | A6 | A7 | A11 | A9 | A6 |

| Kazakhstan | A8 | A11 | A3 | A8 | A2 | A12 | A8 | A1 | A2 | A12 | A2 | A8 | A2 | A1 | A6 |

| Kyrgyzstan | A13 | A6 | A8 | A13 | A6 | A3 | A13 | A6 | A3 | A13 | A6 | A5 | A13 | A6 | A5 |

| Tajikistan | A13 | A11 | A6 | A11 | A6 | A13 | A11 | A6 | A1 | A11 | A6 | A5 | A11 | A6 | A5 |

| Uzbekistan | A1 | A8 | A9 | A8 | A1 | A11 | A6 | A8 | A11 | A6 | A8 | A5 | A6 | A5 | A13 |

| Turkmenistan | A11 | A8 | A2 | A11 | A8 | A2 | A11 | A8 | A2 | A11 | A5 | A8 | A11 | A5 | A8 |

| Afghanistan | A13 | A7 | A10 | A13 | A7 | A9 | A13 | A9 | A7 | A13 | A7 | A9 | A13 | A9 | A7 |

| Syria | A11 | A7 | A10 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A13 | A9 | A10 | A13 | A11 | A9 | A13 | A11 | A9 |

| Kuwait | A6 | A3 | A8 | A3 | A6 | A2 | A10 | A3 | A6 | A6 | A9 | A3 | A6 | A3 | A2 |

| Israel | A13 | A9 | A7 | A13 | A10 | A7 | A13 | A10 | A5 | A13 | A7 | A5 | A13 | A7 | A5 |

| Iraq | A13 | A9 | A7 | A9 | A7 | A11 | A9 | A7 | A11 | A7 | A9 | A11 | A9 | A11 | A7 |

| Iran | A11 | A6 | A10 | A11 | A10 | A6 | A10 | A11 | A6 | A11 | A6 | A8 | A11 | A10 | A6 |

| Azerbaijan | A10 | A2 | A1 | A10 | A7 | A8 | A10 | A7 | A11 | A10 | A7 | A11 | A10 | A7 | A11 |

| Oman | A11 | A6 | A3 | A11 | A3 | A6 | A3 | A11 | A6 | A11 | A3 | A2 | A11 | A12 | A2 |

| Lebanon | A7 | A10 | A6 | A7 | A10 | A9 | A9 | A10 | A7 | A7 | A10 | A8 | A7 | A12 | A10 |

| Qatar | A10 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A11 | A3 | A10 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A12 | A11 |

| Armenia | A10 | A7 | A11 | A10 | A13 | A7 | A10 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A13 | A11 | A13 | A10 | A11 |

| Turkey | A9 | A5 | A10 | A7 | A10 | A9 | A10 | A7 | A9 | A9 | A7 | A1 | A7 | A9 | A5 |

| Jordan | A9 | A3 | A13 | A3 | A4 | A13 | A13 | A3 | A4 | A13 | A4 | A9 | A13 | A7 | A4 |

| Yemen | A8 | A1 | A9 | A1 | A9 | A8 | A9 | A1 | A8 | A13 | A9 | A1 | A1 | A10 | A9 |

| Saudi Arabia | A9 | A6 | A8 | A8 | A6 | A1 | A8 | A6 | A10 | A9 | A10 | A8 | A10 | A9 | A1 |

| China | A9 | A11 | A1 | A9 | A7 | A11 | A9 | A7 | A10 | A10 | A9 | A7 | A7 | A11 | A10 |

| Mongolia | A11 | A13 | A3 | A13 | A11 | A3 | A11 | A12 | A13 | A12 | A11 | A13 | A12 | A3 | A11 |

| Russia | A9 | A11 | A1 | A9 | A10 | A11 | A9 | A11 | A8 | A11 | A10 | A8 | A11 | A10 | A8 |

| Italy | A4 | A9 | A12 | A4 | A12 | A2 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A9 | A12 | A4 |

| Netherlands | A12 | A6 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A6 | A12 | A2 | A3 | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A4 |

| Austria | A12 | A11 | A2 | A12 | A11 | A4 | A11 | A12 | A4 | A11 | A12 | A3 | A11 | A12 | A9 |

| Belgium | A12 | A3 | A5 | A12 | A3 | A5 | A12 | A3 | A5 | A12 | A3 | A9 | A12 | A3 | A5 |

| France | A12 | A9 | A5 | A12 | A5 | A9 | A12 | A5 | A9 | A12 | A9 | A5 | A12 | A9 | A5 |

| Spain | A9 | A12 | A4 | A12 | A9 | A4 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A12 | A4 | A9 |

| Portugal | A12 | A4 | A10 | A12 | A4 | A10 | A12 | A4 | A10 | A12 | A4 | A10 | A12 | A4 | A10 |

| United Kingdom | A12 | A10 | A9 | A12 | A10 | A9 | A12 | A9 | A10 | A12 | A9 | A2 | A12 | A9 | A4 |

| Ireland | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A4 |

| Switzerland | A12 | A4 | A3 | A12 | A3 | A4 | A12 | A3 | A4 | A12 | A2 | A3 | A12 | A3 | A4 |

| Greece | A12 | A4 | A9 | A9 | A12 | A4 | A12 | A9 | A4 | A12 | A9 | A4 | A12 | A9 | A4 |

| Germany | A12 | A4 | A5 | A12 | A4 | A5 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A12 | A9 | A4 | A9 | A12 | A4 |

| Poland | A4 | A10 | A2 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A3 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 |

| Croatia | A4 | A10 | A2 | A4 | A12 | A2 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 |

| Czech Republic | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 |

| Slovakia | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A4 | A5 |

| Albania | A1 | A4 | A13 | A13 | A2 | A4 | A2 | A13 | A4 | A2 | A4 | A13 | A2 | A4 | A8 |

| Bulgaria | A10 | A2 | A4 | A10 | A12 | A3 | A3 | A10 | A4 | A3 | A10 | A4 | A3 | A4 | A2 |

| Hungary | A3 | A2 | A12 | A3 | A12 | A4 | A3 | A12 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A12 | A2 | A3 | A12 |

| Lithuania | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A2 |

| Ukraine | A11 | A10 | A4 | A11 | A10 | A4 | A11 | A1 | A4 | A11 | A10 | A9 | A11 | A10 | A1 |

| Moldova | A5 | A11 | A3 | A11 | A5 | A8 | A11 | A5 | A13 | A11 | A5 | A13 | A11 | A5 | A13 |

| Romania | A5 | A4 | A2 | A5 | A4 | A2 | A5 | A4 | A2 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 |

| Slovenia | A3 | A4 | A5 | A3 | A12 | A5 | A3 | A12 | A5 | A3 | A5 | A4 | A3 | A5 | A4 |

| Belarus | A11 | A8 | A7 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A11 | A7 | A10 | A11 | A7 | A3 | A11 | A7 | A3 |

| Serbia | A11 | A5 | A1 | A11 | A5 | A8 | A11 | A5 | A8 | A11 | A5 | A3 | A11 | A5 | A3 |

| Egypt | A9 | A7 | A6 | A7 | A6 | A9 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 |

| Algeria | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A9 | A6 | A7 | A7 | A6 | A8 | A7 | A6 | A9 |

| Morocco | A9 | A11 | A4 | A11 | A4 | A7 | A11 | A4 | A8 | A11 | A4 | A13 | A11 | A4 | A7 |

| Tunisia | A11 | A8 | A7 | A11 | A8 | A3 | A11 | A1 | A8 | A11 | A8 | A1 | A11 | A8 | A9 |

| Libya | A11 | A7 | A8 | A11 | A7 | A3 | A9 | A11 | A1 | A9 | A1 | A11 | A1 | A11 | A7 |

| Sudan | A7 | A11 | A6 | A7 | A11 | A9 | A7 | A11 | A10 | A7 | A11 | A10 | A13 | A7 | A11 |

| Ethiopia | A13 | A7 | A10 | A13 | A7 | A10 | A13 | A7 | A10 | A7 | A13 | A11 | A7 | A11 | A1 |

| Kenya | A11 | A9 | A1 | A11 | A9 | A1 | A9 | A13 | A11 | A11 | A9 | A8 | A11 | A9 | A13 |

| Tanzania | A13 | A11 | A6 | A13 | A11 | A6 | A13 | A11 | A6 | A11 | A13 | A6 | A11 | A9 | A6 |

| New Zealand | A5 | A4 | A2 | A5 | A4 | A2 | A5 | A4 | A2 | A5 | A4 | A2 | A9 | A5 | A4 |

| Australia | A5 | A12 | A10 | A12 | A2 | A5 | A12 | A2 | A5 | A12 | A2 | A5 | A12 | A5 | A9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, W.; Shan, Y.; Deng, Y.; Fu, N.; Duan, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J. Geopolitical Risk Evolution and Obstacle Factors of Countries along the Belt and Road and Its Types Classification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021618

Hu W, Shan Y, Deng Y, Fu N, Duan J, Jiang H, Zhang J. Geopolitical Risk Evolution and Obstacle Factors of Countries along the Belt and Road and Its Types Classification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021618

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Wei, Yue Shan, Yun Deng, Ningning Fu, Jian Duan, Haining Jiang, and Jianzhen Zhang. 2023. "Geopolitical Risk Evolution and Obstacle Factors of Countries along the Belt and Road and Its Types Classification" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021618

APA StyleHu, W., Shan, Y., Deng, Y., Fu, N., Duan, J., Jiang, H., & Zhang, J. (2023). Geopolitical Risk Evolution and Obstacle Factors of Countries along the Belt and Road and Its Types Classification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021618