Research on the Effect of Evidence-Based Intervention on Improving Students’ Mental Health Literacy Led by Ordinary Teachers: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Coding

2.4. Publication Bias and Sensitivity Testing

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Combined Effect Size Calculation

2.5.2. Model Selection and Heterogeneity Testing

3. Results

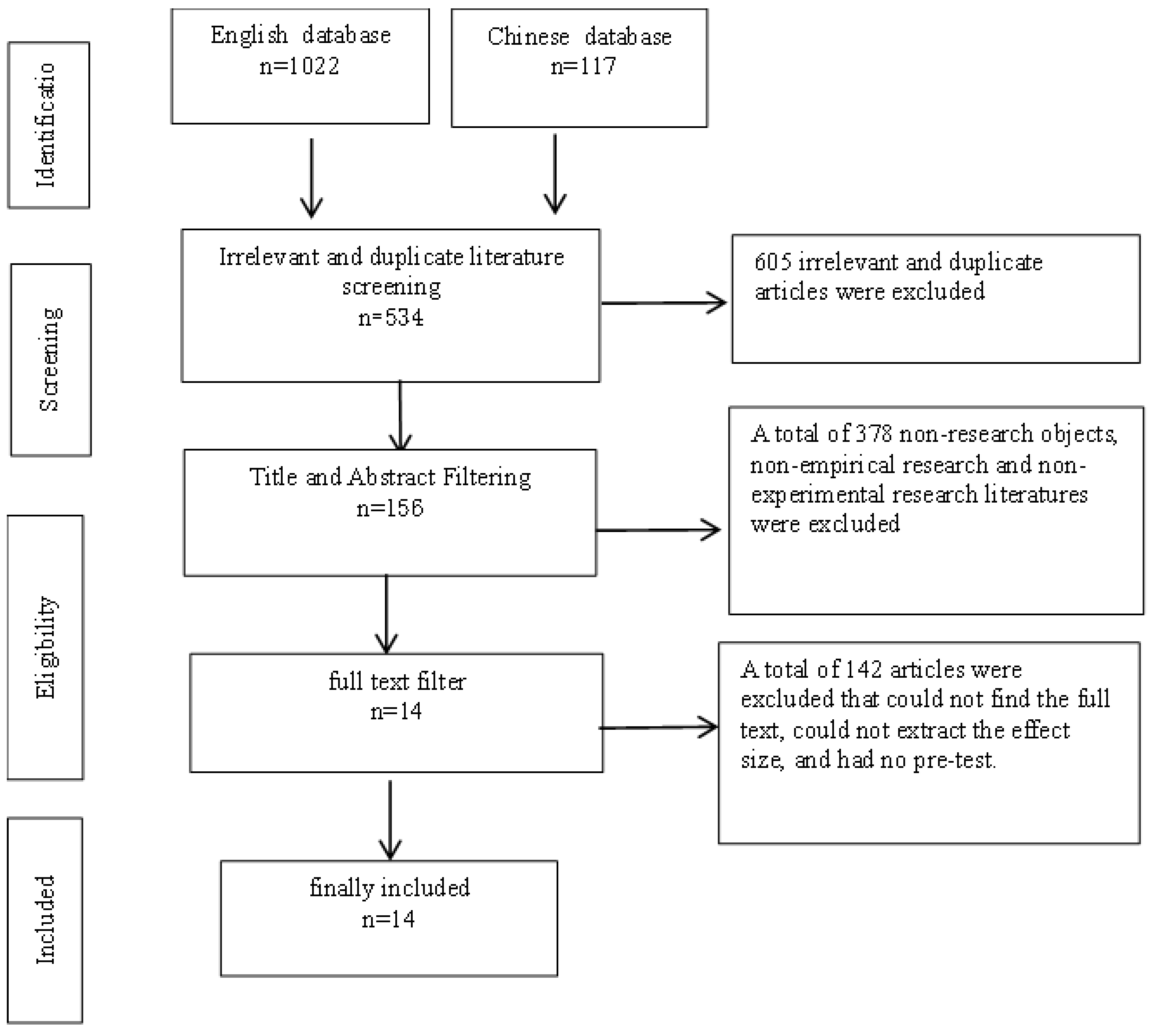

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Description of Included Studies

3.3. Outcomes

3.3.1. Publication Bias and Heterogeneity Testing

3.3.2. Main Effects and Sensitivity Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author (Year of Publication) | Country | Learning Phase | Experiment Type | Measurement Type | Do Teachers Have Prior Training | Teacher’s Teaching Method | How Long the Student Received the Intervention | Measurement Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Milin (2016) [37] | Canada | middle school student | RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | Classroom Activities, Stories, Videos, Interviews | 1–2 months | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Theda Rose (2017) [22] | USA | middle school student | Non-RCT | Pre-test, post-test, follow-up test (five months) | Yes | Educational guidance, experiential exercises, case studies, group reflections | 8 h once or 4 h twice | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| help-seeking | ||||||||

| Alan Mcluckie (2014) [26] | Canada | middle school student | Non-RCT | Pre-test, post-test, follow-up test (two months) | No | classroom teaching | not reported | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Paul B. Naylor (2009) [23] | UK | middle school student | RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | Paper materials, videos, discussions, role-plays, Internet searches | 6 courses of 50 min each/one session per week | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| help-seeking | ||||||||

| Amanda J. Nguyen (2020) [27] | Vietnam | middle school student | RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | classroom teaching | 45-min classes twice a week for five weeks | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Cambodia | Knowledge | |||||||

| stigma | ||||||||

| Yael Perry (2014) [24] | Australia | middle school student | RCT | Pre-test, post-test, follow-up test (six months) | Yes | Classroom teaching, online resources | 5–8 weeks, 10 total Hours | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| help-seeking | ||||||||

| Stan Kutcher (2015) [16] | Canada | middle school student | Non-RCT | Pre-test, post-test, follow-up test (two months) | Yes | Classroom instruction, written materials, animations, discussions, classroom activities, online resources | 3 days (10–12 lessons) | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Ingunn Skre (2013) [38] | Norway | middle school student | Non-RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | Teaching, participating in tasks and activities | 3 days | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Amy C. Waston (2016) [39] | USA | middle school student | Non-RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | Scene simulation, animation video | 5–6 courses (45 min/session) | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Darcy A. Santor (2007) [36] | Canada | middle school student | Non-RCT | pre-test, post-test | No | Classroom teaching, online resources | Twice (1 h/each time) | help-seeking |

| Robert H. Aseltine Jr (2004) [40] | USA | high school student | RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | video, discussion | Two days | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| Milica (2009) [41] | Serbia | high school student | Non-RCT | pre-test, post-test | No | Classroom teaching, seminars | Six weeks | stigma |

| Amy B. Spagnolo (2008) [42] | USA | middle school student | Non-RCT | pre-test, post-test | Yes | Lectures, discussions, direct contact | 1 h | stigma |

| Eliza S.Y. Lai (2016) [25] | China Hong Kong | middle school student | Non-RCT | Pre-test, post-test, follow-up test (five months) | Yes | Lectures, animation videos | 10 lessons, 45–60 min/each | Knowledge |

| stigma | ||||||||

| help-seeking |

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 6, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Available online: http://library.oum.edu.my/oumlib/content/catalog/621241 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Methods and Data Sources for Global Burden of Disease Estimates 2000–2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/global-health-estimates (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Kelly, C.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Wright, A. Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, s26–s30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusch, N.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Henderson, C.; Flach, C.; Thornicroft, G. Public knowledge and attitudes as predictors of help seeking and disclosure in mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 6, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Avenevoli, S.; Costello, J. Severity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutcher, S. Facing the challenge of care for child and youth mental health in Canada: A critical commentary, five suggestions for change and a call to action. Healthc. Q. 2011, 14, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 5th ed.; Thapar, A., Bishop, D., Pine, D.S., Scott, S., Stebenson, S.J., Taylor, E.A., Thapar, A., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhihong, R.; Chunxiao, Z.; Fan, T.; Yupeng, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, Z.; Tan, M.; Jiang, G. A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Chinese Mental Health Literacy Intervention. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2020, 52, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornicroft, G. Most people with mental illness are not treated. Lancet 2007, 370, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Flisher, A.J.; Hetrick, S.; McGorry, P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007, 369, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolan, P.H.; Dodge, K.A. Children’s mental health as a primary care and concern: A system for comprehensive support and service. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, C.; McEwan, K.; Shepherd, C.A.; Offord, D.R.; Hua, J.M. A public health strategy to improve the mental health of Canadian children. Can. J. Psychiatry 2005, 27, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. Mental health literacy: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1997, 66, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutcher, S.; Bagnell, A.; Wei, Y. Mental health literacy in secondary schools: A Canadian approach. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2015, 24, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajawu, L.; Chingarande, S.D.; Jack, H.; Ward, C.; Taylor, T. What do African traditional medical practitioners do in the treatment of mental disorders in Zimbabwe? Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2016, 9, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.; Hoagwood, K.; Kutash, K.; Seidman, E. Toward the integration of education and mental health in schools. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 37, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGorry, P.D.; Purcell, R.; Goldstone, S.; Amminger, G.P. Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance use disorders: Implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2011, 24, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowling, L. Developing and Sustaining Mental Health and Well-being in Australian Schools. In International School Mental Health for Adolescents: Global Opportunities and Challenges; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Triandis, H.; Kanfer, F.; Becker, M.; Middlestadt, S.; Eichler, A. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change. In Handbook of Health Psychology; Baum, A., Revenson, T., Singer, J., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Theda, R.; Leitch, J.; Collins, K.S.; Frey, J.J.; Osteen, J.F. Effectiveness of Youth Mental Health First Aid USA for Social Work Students. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2017, 29, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, P.B.; Cowie, H.A.; Walters, S.J.; Talamelli, L.; Dawkins, J. Impact of a mental health teaching programme on adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 194, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Y.; Petrie, K.; Cavanagh, H.B.L.; Clarke, D.; Winslade, M.; Pavlovic, H.D.; Manicavasagar, V.; Christensen, H. Effects of a classroom-based educational resource on adolescent mental health literacy: A cluster randomised controlled trial. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.S.; Kwok, C.L.; Wong, P.W.; Fu, K.W.; Law, Y.W.; Yip, P.S. The Effectiveness and Sustainability of a Universal School-Based Programme for Preventing Depression in Chinese Adolescents: A Follow-Up Study Using Quasi Experimental Design. PLoS ONE 2016, 26, e0149854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mcluckie, A.; Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Weaver, C. Sustained improvements in students’ mental health literacy with use of a mental health curriculum in Canadian schools. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.J.; Dang, H.M.; Bui, D.; Phoeun, B.; Weiss, B. Experimental Evaluation of a School Based Mental Health Literacy Program in two Southeast Asian Nations. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 6, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Hayden, J.A.; Kutcher, S.; Zygmunt, A.; McGrath, P. The effectiveness of school mental health literacy programs to address knowledge, attitudes and help seeking among youth. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2013, 7, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Ross, A.; Reavley, N.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health first aid training: Effects on knowledge, stigma, and helping behaviour. PloS ONE 2018, 13, e0197102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hills Dale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Foo, J.C.; Nishida, A.; Ogawa, S.; Togo, F.; Sasaki, T. Mental health literacy programs for school teachers: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 14, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, I.; Vila, I.; Redondo, R. What makes implementation intention interventions effective for promoting healthy eating behaviour? A meta-regression. Appetite 2019, 140, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkeljon, A.; Baldwin, S.A. An introduction to meta-analysis for psychotherapy outcome research. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ Clin. Res. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, A.; Santor, C.P.; John, C.; LeBlanc, V.K. Facilitating Help Seeking Behavior and Referrals for Mental Health Difficulties in School Aged Boys and Girls: A School-Based Intervention. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 36, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milin, R.; Kutcher, S.; Stephen, P.; Lewis, S.; Walker, S.; Yifeng, W.; Ferrill, N.; Armstrong, M.A. Impact of a Mental Health Curriculum for High School Students on Knowledge and Stigma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 3, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skre, I.; Friborg, O.; Breivik, C.; Johnsen, L.I.; Arnesen, Y.; Wang, C.E.A. A school intervention for mental health literacy in adolescents: Effects of a non-randomized cluster controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.C.; Otey, E.; Westbrook, A.L.; Gardner, A.L.; Lamb, T.A.; Corrigan, P.W.; Fenton, W.S. Changing Middle Schoolers' Attitudes About Mental Illness Through Education. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 3, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, J.D.; Crittenden, K.; Dalrymple, K.L. Knowledge of social anxiety disorder relative to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among educational professionals. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004, 33, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pejović-Milovančević, M.; Lečić-Toševski, D.; Lazar Tenjović, S.; Popović-Deušić, S.; Draganić-Gajić, S. Changing Attitudes of High School Students towards Peers with Mental Health Problems. Psychiatr. Danub. 2009, 21, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo, A.B.; Murphy, A.A.; Librera, L.A. Reducing Stigma by Meeting and Learning from People with Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2008, 3, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Coding |

|---|---|

| outcome variable | Knowledge = 1; stigma = 2; help-seeking = 3 |

| Outcome Variable | k | Publication Bias Test | Heterogeneity Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egger’s Intercept | SE | 95% CI | p | Q-Value | df | p | I2 | ||

| immediate effect of intervention | 31 | 0.280 | 2.108 | (−4.031, 4.591) | 0.895 | 867.482 | 30 | 0.000 | 96.542 |

| Intervention delay effect | 13 | 2.621 | 2.332 | (−2.513, 7.756) | 0.285 | 166.027 | 12 | 0.000 | 92.772 |

| Outcome Variable | k | g (95% CI) | Sensitivity Test | Heterogeneity Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g (95% CI) | Qw | df | p | I2 | ||||

| Knowledge | immediate effect of intervention | 12 | 0.622 (0.395, 0.849) | 0.622 (0.395, 0.849) | 396.399 | 11 | 0.000 | 97.225 |

| Intervention delay effect | 5 | 0.752 (0.671, 0.834) | 0.752 (0.671, 0.834) | 3.480 | 4 | 0.481 | 0.000 | |

| stigma | immediate effect of intervention | 14 | 0.262 (0.170, 0.354) | 0.262 (0.170, 0.354) | 79.760 | 13 | 0.000 | 83.701 |

| Intervention delay effect | 5 | 0.288 (0.123, 0.452) | 0.288 (0.123, 0.452) | 12.648 | 4 | 0.013 | 68.374 | |

| Help-seeking | immediate effect of intervention | 5 | 0.078 (−0.033, 0.189) | 0.078 (−0.033, 0.189) | 7.662 | 4 | 0.105 | 47.796 |

| Intervention delay effect | 3 | 0.029 (−0.065, 0.123) | 0.029 (−0.065, 0.123) | 0.497 | 2 | 0.780 | 0.000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, Y.; Ameyaw, M.A.; Liang, C.; Li, W. Research on the Effect of Evidence-Based Intervention on Improving Students’ Mental Health Literacy Led by Ordinary Teachers: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020949

Liao Y, Ameyaw MA, Liang C, Li W. Research on the Effect of Evidence-Based Intervention on Improving Students’ Mental Health Literacy Led by Ordinary Teachers: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020949

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Yuanyuan, Moses Agyemang Ameyaw, Chen Liang, and Weijian Li. 2023. "Research on the Effect of Evidence-Based Intervention on Improving Students’ Mental Health Literacy Led by Ordinary Teachers: A Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020949

APA StyleLiao, Y., Ameyaw, M. A., Liang, C., & Li, W. (2023). Research on the Effect of Evidence-Based Intervention on Improving Students’ Mental Health Literacy Led by Ordinary Teachers: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020949