Barriers to Health and Social Services for Unaccounted-For Female Migrant Workers and Their Undocumented Children with Precarious Status in Taiwan: An Exploratory Study of Stakeholder Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

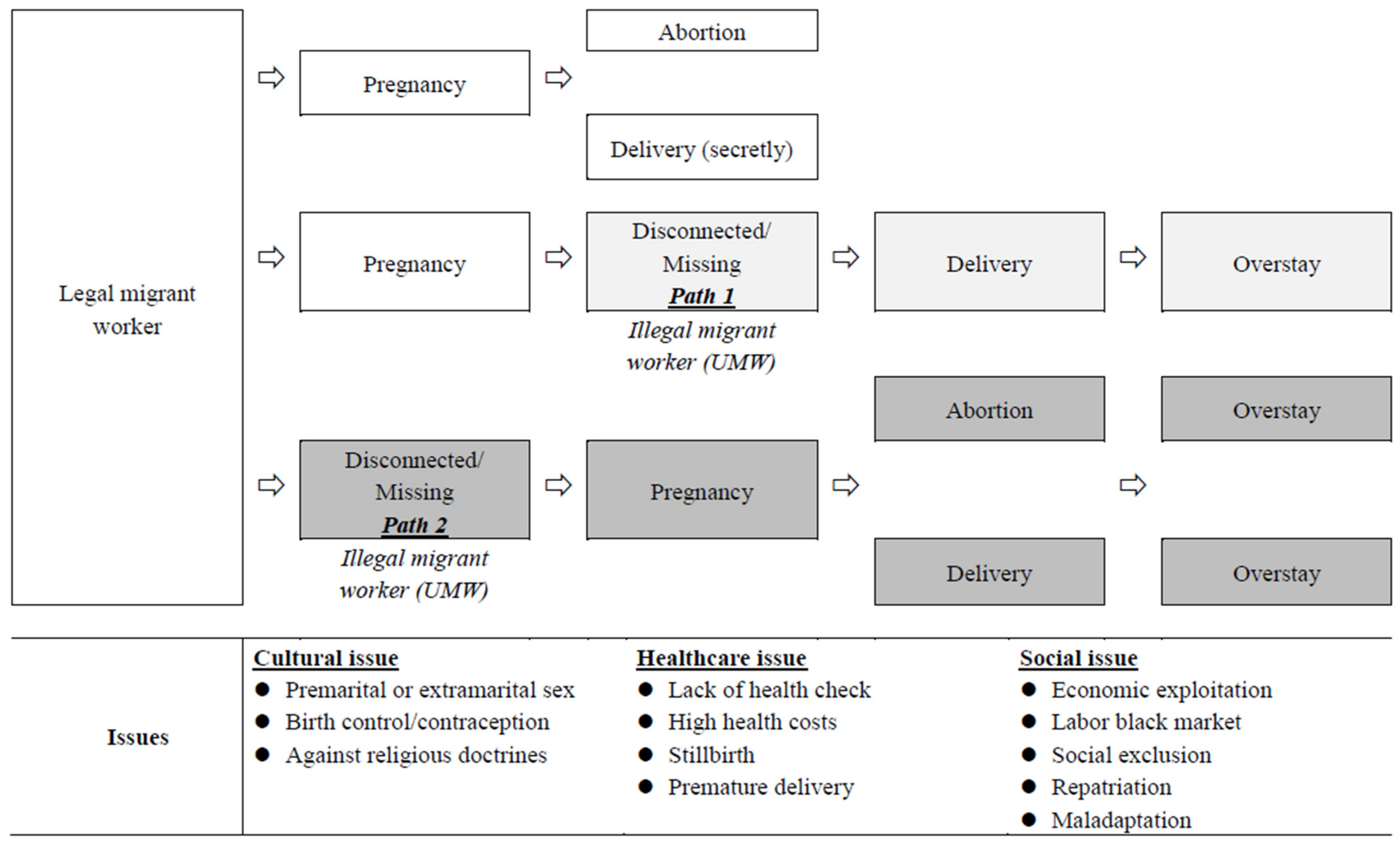

1.1. Unaccounted-For Migrant Workers in Taiwan

1.2. Precarious Status of Unaccounted-For Migrant Workers and Undocumented Children

1.3. Services for Migrant Mothers and Undocumented Children

- (a)

- To identify professionals’ views the needs of UMWs and their undocumented children.

- (b)

- To explore the healthcare and childcare service access for UMWs and their undocumented children from the views of professionals in related systems.

- (c)

- To understand current service access limitations among UMWs and their undocumented children, for practical implications.

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Health Issue and Access to Healthcare

In Islam, birth control is not allowed or encouraged. After becoming pregnant, MWs worry that their employer will discover it, so they will hide it and give birth secretly. That also increases the risk of stillbirth. Married female MWs may be afraid of returning to their home country because they have a relationship in Taiwan that violates their religious doctrine.(Mosque staff, interviewed on 16 April 2020)

UMWs are worried that if they go to a large hospital, they will be easily caught, and then not allowed to work in Taiwan and deported. So, they are likely to go to small clinics and even do not have prenatal exams. Therefore, some children’s diseases could not be identified earlier. Women would still have health risks due to sudden hormonal changes after giving birth. Although migrant mothers have been informed about their health condition, they may still decide to leave soon after childbirth.(Hospital social workers, interviewed on 3 May 2020)

Large hospitals are often the last resort for children with serious illness. Many children are sent to us because only we can provide special treatments. When a child has serious illnesses that needs to be addressed urgently, preparing the necessary documentation often delays the medical treatment.(Hospital social workers, interviewed on 3 May 2020)

3.2. Childcare and Child Development

At present, we serve as a bridge to connect mothers and local governments. … Some administrators in other counties may think that these migrant mothers would run away, take advantage of Taiwan’s social welfare resources, like to play, and are irresponsible. Indeed, many migrant mothers came to us in tears, saying that they are not allowed to visit their children, have difficulties applying for documents, or fear that they will be arrested if they do not return to their country soon. They [public administrators] are very unfriendly.(Placement social worker, interviewed on 13 August 2020)

Child Development and Education

In some cases, the local government has been the official guardian of a child. But when the biological mother was found, and they must be deported together. Many children are very resistant and present symptoms of anxiety and bedwetting. The placement workers try to help these children by familiarizing them with their future living environment by providing photos of their mother and local communities in Indonesia, as well as teaching the language.(Local government administrator, interviewed on 11 May 2020)

3.3. Permanency Planning for Undocumented Children

3.3.1. Naturalization and Adoption

If the birth mother is missing, the National Immigration Agency will search within the Taiwan borders for six months. If the mother has left Taiwan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will search for three months. If children’s mother cannot be found, the Ministry of Interior will determine the child’s Taiwan nationality through the adoption and naturalization process.(Local government administrator, interviewed on 11 May 2020)

3.3.2. Repatriation (Voluntary Departure) with Birth Parent(s)

Although children are under the guardianship of our local government, they do not have a Taiwanese identity. When they are prepared for departure, the National Immigration Agency helps prepare travel documents, and the foreign country’s economic and trade office helps verify these documents. Thus, after the mothers bring their children back to their country, they can claim the child’s nationality more easily.(Local government administrator, interviewed on 11 May 2020)

The female MWs already have the child [in Taiwan]; if the spouse [in home country] cannot agree upon the reality, they would divorce. … Mostly they choose to divorce and ask their birth family to care for the child instead of sending the child to an orphanage. … Because the mothers would keep sending money back to the family … if they send the child to an orphanage, that is definitely for adoption.(Foreign country’s Economic and Trade Office, online interviewed on 24 April 2020)

3.3.3. Repatriation: Child Only

3.3.4. Uncertain Journey and Permanency

These children would be very anxious. [wondering if] this person is my mom, and how do I get along with her? And I am going to leave Taiwan and go back to my original country … This is a big challenge for these children because their future is unknown. They don’t know about the community, the language, the culture … but according to the current Taiwanese law, they must go back to their country with their mother.(Local government administrator, interviewed on 11 May 2020)

I think for now we are trying to do our best to care for the children, so that they [MW mothers] can securely work, save money, pay debts, and return home with their children. Fewer mothers are abandoning their children. We have heard that some mothers would abandon their children, or after going back to Indonesia, they would give or sell their children to other people or local orphanages in Indonesia.(Foreign country’s economic and trade office, online interviewed on 24 April 2020)

4. Discussion

4.1. Advocacy for Protection for UMWs and Undocumented Children’s Basic Rights

4.2. Advocacy for Culturally Appropriate Practice

4.3. Advocacy for Interdisciplinary, Interministerial, and Transnational Collaboration

4.4. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Labor. Statistics of Labors. Available online: https://statfy.mol.gov.tw/statistic_DB.aspx (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Dong, J.-H. Children of Migrant Workers in Taiwan: No Nationality, No Identity, Who Can Give Them a “Home”? Opinion CW. 2018. Available online: https://opinion.cw.com.tw/blog/profile/52/article/6790 (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Ministry of the Interior National Immigration Agency (MINIA). Statistics of Unaccounted-for Migrant Workers; MINIA: Taipei, Taiwan, 2019. Available online: https://www.immigration.gov.tw/5385/7344/7350/8943/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Tang, H.-T. Stateless Children of Migrant Workers in Taiwan: Intending to Entitle an ID. Up Media. Available online: https://www.upmedia.mg/news_info.php?SerialNo=11234 (accessed on 28 January 2017).

- Ministry of the Interior National Immigration Agency (MINIA). Unaccounted-for Migrant Workers Give Birth in Taiwan. Children’s Rights Have to Be Protected. 2020. Available online: https://www.immigration.gov.tw/5385/7229/7238/236777/ (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Social and Family Affairs Administration in Ministry of Health and Welfare. Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of the ROC/Taiwan on the Implementation. Taipei, Taiwan: Author. Available online: https://crc.sfaa.gov.tw/Document/Detail?documentId=13F7A111-E743-4AC2-B9C6-AEEE70AF85D9 (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Bicocchi, L. Undocumented Children in Europe: Ignored Victims of Immigration Restrictions. In Children without a State: A Global Human Rights Challenge; Bhabha, J., Ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar, C.; Perreira, K.M. Undocumented and unaccompanied: Children of migration in the European Union and the United States. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Han, P.-C. The Relationship between the Change in Migrant Worker Policy and the Increase in the Number of Unaccounted-for Migrant Workers; Ministry of the Interior National Immigration Agency: Taiwan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-J. Research on Migrant Worker Crimes and Regulations. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.-K.; Lin, H.-F. Research of Vietnamese Female Foreign Workers’ Experience during Fleeing. Police Sci. Q. 2008, 38, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Control Yuan. Investigation of Supervisory Committee Wang You-Ling and Wang Mei-Yu on Stateless Children of Migrant Workers Promotes the Establishment of Harmony Home Placement and Formal Care of Undocumented Children. Available online: https://www.cy.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=528&s=16344 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Ruiz-Casares, M.; Rousseau, C.; Derluyn, I.; Watters, C.; Crepeau, F. Right and access to healthcare for undocumented children: Addressing the gap between international conventions and disparate implementations in North America and Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families. Adopted by General Assembly Resolution 45/158 of 18 December 1990. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/cmw.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Passel, J.S. The Size and Characteristics of the Unauthorized Migrant Population in the US: Estimates Based on the March 2005 Current Population Survey; Pew Hispanic Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2006/03/07/size-and-characteristics-of-the-unauthorized-migrant-population-in-the-us/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Lynch, M. Without Face or Future: Stateless Infants, Children, and Youth. In Children and Migration; Ensor, M.O., Goździak, E.M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorling, K. Growing up in a Hostile Environment: The Rights of Undocumented Migrant Children in the UK; Coram Children's Legal Centre: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kohki, A. Overview of Stateless: International and Japanese Context; UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/crc/ (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Comandini, O.; Cabras, S.; Marini, E. Nutritional evaluation of undocumented children: A neglected health issue affecting the most fragile people. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants. Access to Health Care for Undocumented Migrants in Europe; Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, R.G. On the rights of undocumented children. Society 2009, 46, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E. The undocumented: Educating the children of migrant workers in America. Biling. Res. J. 2003, 27, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, L.; Ugarriza, D.N. The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2000, 22, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Reasonable Efforts to Preserve or Reunify Families and Achieve Permanency for Children; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/reunify.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Zhang, W.-C. Indonesian Female Foreign Worker Sentenced to 6 Months, Probation 2 Years Due to Drop the Stillbirth Born. Available online: https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/society/breakingnews/1928731 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Constable, N. Tales of two cities: Legislating pregnancy and marriage among foreign domestic workers in Singapore and Hong Kong. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 3491–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, B.F.X.; Iskandar, K. The Illegal Network of Foreign Workers: The Missing Indonesian Migrant Workers in Japan. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 8583–8595. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger, D.; Ueno, K.; Hong, K.T.; Ochiai, E. From foreign trainees to unauthorized workers: Vietnamese migrant workers in Japan. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2011, 20, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, C. Contested statelessness in Sabah, Malaysia: Irregularity and the politics of recognition. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2017, 15, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, C. Statelessness and the lives of the children of migrants in Sabah, East Malaysia. Tilburg Law Rev. 2014, 19, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Professional Position | Role | Number of Interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Local government (social welfare sector) | Administrator | 3 |

| Child welfare placement (residential care) | Social worker | 3 |

| Migrant worker detention center | Administrator | 2 |

| Foreign country’s economic and trade office | Administrator | 1 |

| Hospital | Social worker | 1 |

| Mosque (religious center) | Staff | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.S.; Lin, C.-H. Barriers to Health and Social Services for Unaccounted-For Female Migrant Workers and Their Undocumented Children with Precarious Status in Taiwan: An Exploratory Study of Stakeholder Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020956

Wang MS, Lin C-H. Barriers to Health and Social Services for Unaccounted-For Female Migrant Workers and Their Undocumented Children with Precarious Status in Taiwan: An Exploratory Study of Stakeholder Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020956

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ming Sheng, and Ching-Hsuan Lin. 2023. "Barriers to Health and Social Services for Unaccounted-For Female Migrant Workers and Their Undocumented Children with Precarious Status in Taiwan: An Exploratory Study of Stakeholder Perspectives" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020956