The Impact of Psychotrauma and Emotional Stress Vulnerability on Physical and Mental Functioning of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Cumulative Trauma Exposure

2.2.2. Clinical GI Disease Activity

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Disease Activity Group Differences in Cumulative Traumatization and Neuroticism

3.3. Correlations between Experiential Vulnerability Factors and Disease Activity

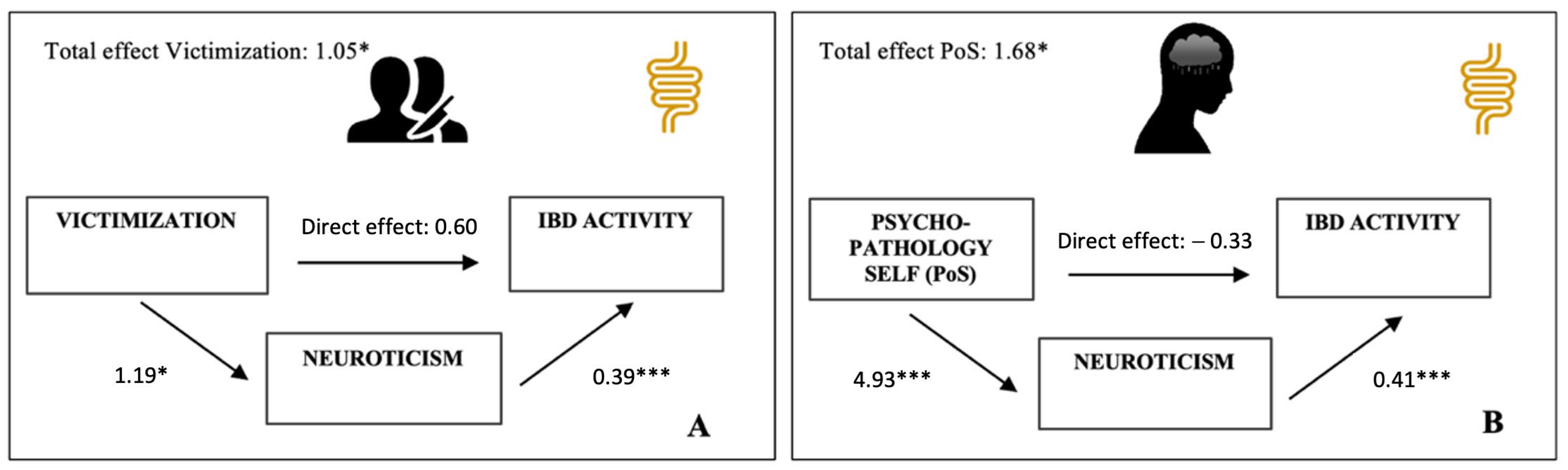

3.4. Effect of Neuroticism on the Relationship between Trauma and IBD Activity

3.5. Effect of Neuroticism on the Relationship between Trauma and Functional GI Symptom Scores

3.6. Effect of Neuroticism on the Relationship between Trauma and Disease-Related QoL Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Andrea, W.; Sharma, R.; Zelechoski, A.; Spinazzola, J. Physical Health Problems after Single Trauma Exposure. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2011, 17, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, C.; Dooley, C.; Layte, R.; Kenny, R. The Lasting Legacy of Childhood Adversity for Disease Risk in Later Life. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.; Sefl, T.; Ahrens, C.E. The Physical Health Consequences of Rape: Assessing Survivors’ Somatic Symptoms in a Racially Diverse Population. Women’s Stud. Q. 2003, 31, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, J.F.M.; Paghdar, S.; Khan, T.M.; Patel, N.P.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Tsouklidis, N. Stress and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clear Mind, Happy Colon. Cureus 2022, 14, e25006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballou, S.; Feingold, J.H. Stress, Resilience, and the Brain-Gut Axis: Why Is Psychogastroenterology Important for all Digestive Disorders? Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 51, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craven, M.R.; Quinton, S.; Taft, T.H. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patient Experiences with Psychotherapy in the Community. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2019, 26, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefer, L.; Sayuk, G.; Bratten, J.; Rahimi, R.; Jones, M.P. Multicenter study of gastroenterologists’ ability to identify anxiety and depression in a new patient encounter and its impact on diagnosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008, 42, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D. Sexual and Physical Abuse in Women with Functional or Organic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 113, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leserman, J.; Drossman, D.; Li, Z.; Toomey, T.; Nachman, G.; Glogau, L. Sexual and Physical Abuse History in Gastroenterology Practice. Psychosom. Med. 1996, 58, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.A.; Katon, W.J.; Roy-Byrne, P.P.; Jemelka, R.P.; Russo, J. Histories of Sexual Victimization in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome or Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150, 1502–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, F.; Pallotta, N.; Calabrese, E.; Pezzotti, P.; Corazziari, E. Prevalence of Sexual and Physical Abuse and Its Relationship with Symptom Manifestations in Patients with Chronic Organic and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Dig. Liver Dis. 2003, 35, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarikova, H.; Kascakova, N.; Furstova, J.; Zelinkova, Z.; Falt, P.; Hasto, J.; Tavel, P. Life Stressors in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Comparison with a Population-Based Healthy Control Group in the Czech Republic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drossman, D.; Li, Z.; Leserman, J.; Toomey, T.; Hu, Y. Health Status by Gastrointestinal Diagnosis and Abuse History. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, R.A.; Maunder, R.G.; Stempak, J.M.; Silverberg, M.S.; Hart, T.L. Attachment, childhood abuse, and IBD-related quality of life and disease activity outcomes. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanuri, N.; Cassell, B.; Bruce, S.E.; White, K.S.; Gott, B.M.; Gyawali, C.P.; Sayuk, G.S. The impact of abuse and mood on bowel symptoms and health-related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomann, A.; Lis, S.; Reindl, W. P796 Adverse Childhood Events and Psychiatric Comorbidity in a Single-Centre IBD-Cohort. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 12, S514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, H.; Möller, S.; Wilding, H.; Apputhurai, P.; Moore, G.; Knowles, S. Prevalence and Impact of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Gastrointestinal Conditions: A Systematic Review. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 4109–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leserman, J.; Drossman, D. Relationship of Abuse History to Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Symptoms: Some possible mediating mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abus. 2007, 8, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V. Long-Term Medical Consequences of Incest, Rape, and Molestation. South. Med. J. 1991, 84, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J. Sexual Assault History and Physical Health in Randomly Selected Los Angeles Women. Health Psychol. 1994, 13, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, P. Symptomatology and Health Care Utilization of Women Primary Care Patients Who Experienced Childhood Sexual Abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2000, 24, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechner, M.E.; Vogel, M.E.; Garcia-Shelton, L.M.; Leichter, J.L.; Steibel, K.R. Self-reported medical problems of adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J. Fam. Pract. 1993, 36, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melchior, C.; Wilpart, K.; Midenfjord, I.; Trindade, I.A.; Törnblom, H.; Tack, J.F.; Simrén, M.; Van Oudenhove, L. Relationship between Abuse History and Gastrointestinal and Extraintestinal Symptom Severity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Psychosom. Med. 2022, 84, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Talley, N.; Fett, S.; Zinsmeister, A.; Melton, L. Gastrointestinal Tract Symptoms and Self-Reported Abuse: A Population-Based Study. Gastroenterology 1994, 107, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perona, M.; Benasayag, R.; Perelló, A.; Santos, J.; Zárate, N.; Zárate, P.; Mearin, F. Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Women Who Report Domestic Violence to the Police. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 3, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.; Jones, A.; Dienemann, J.; Kub, J.; Schollenberger, J.; O’Campo, P.; Gielen, A.; Wynne, C. Intimate Partner Violence and Physical Health Consequences. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, A.; Smith, P.; Bethea, L.; King, M.; McKeown, R. Physical Health Consequences of Physical and Psychological Intimate Partner Violence. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000, 9, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y. Gastrointestinal Problems in Modern Wars: Clinical Features and Possible Mechanisms. Mil. Med. Res. 2015, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, J.; Silver, R.; Prause, J. Physical and Mental Health Costs of Traumatic War Experiences among Civil War Veterans. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeay, S.; Harvey, W.; Romaniuk, M.; Crawford, D.; Colquhoun, D.; Young, R.; Dwyer, M.; Gibson, J.; O’Sullivan, R.; Cooksley, G.; et al. Physical Comorbidities of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Australian Vietnam War Veterans. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 206, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulston, K.; Dent, O.; Chapuis, P.; Chapman, G.; Smith, C.; Tait, A.; Tennant, C. Gastrointestinal Morbidity among World War II Prisoners of War: 40 Years on. Med. J. Aust. 1985, 143, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimsdale, J. Survivors, Victims, and Perpetrators; Hemisphere Pub. Corp.: Washington, DC, USA, 1980; pp. 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Krystal, H. Integration and Self Healing: Affect, Trauma, Alexithymia; Analytic Press: Hilsdale, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le, L.; Morina, N.; Schnyder, U.; Schick, M.; Bryant, R.; Nickerson, A. The Effects of Perceived Torture Controllability on Symptom Severity of Posttraumatic Stress, Depression and Anger in Refugees and Asylum Seekers: A Path Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 264, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roemer, L.; Orsillo, S.; Borkovec, T.; Litz, B. Emotional Response at the Time of a Potentially Traumatizing Event and PTSD Symptomatology. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1998, 29, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcioglu, E.; Urhan, S.; Pirinccioglu, T.; Aydin, S. Anticipatory Fear and Helplessness Predict PTSD and Depression in Domestic Violence Survivors. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2017, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overmier, J.; Murison, R. Anxiety and Helplessness in the Face of Stress Predisposes, Precipitates, and Sustains Gastric Ulceration. Behav. Brain Res. 2000, 110, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Li, Y.; Tang, W.; Sun, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yu, S.; Yu, S.; Liu, C.; et al. Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress In Rats Induces Colonic Inflammation. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, E.; Maharshak, N.; Elloumi, H.; Borst, L.; Plevy, S.; Moeser, A. Early Life Stress Triggers Persistent Colonic Barrier Dysfunction and Exacerbates Colitis in Adult IL-10−/− Mice. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, J.; Yang, P.; Ceponis, P.; Vohra, A.; Riddell, R.; Sherman, P.; Perdue, M. Chronic Stress Induces Mast Cell–Dependent Bacterial Adherence and Initiates Mucosal Inflammation in Rat Intestine. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Feng, B.; Oluwole, C.; Struiksma, S.; Chen, X.; Li, P.; Tang, S.; Yang, P. Psychological Stress Induces Eosinophils to Produce Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone in the Intestine. Gut 2009, 58, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Kamada, K.; Mizushima, K.; Higashimura, Y.; Katada, K.; Uchiyama, K.; Handa, O.; Takagi, T.; Naito, Y.; Itoh, Y. Changes in Intestinal Motility and Gut Microbiota Composition in a Rat Stress Model. Digestion 2017, 95, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, R.; Croiset, G.; Akkermans, L.; Wiegant, V. Sensitization of The Colonic Response to Novel Stress after Previous Stressful Experience. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1996, 271, R1270–R1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milde, A.; Sundberg, H.; RØseth, A.; Murison, R. Proactive Sensitizing Effects of Acute Stress on Acoustic Startle Responses and Experimentally Induced Colitis in Rats: Relationship to Corticosterone. Stress 2003, 6, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. Studies of Ulcerative Colitis. III. The nature of psychologic processes. Am. J. Med. 1955, 19, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satchell, L.; Kaaronen, R.; Latzman, R. An Ecological Approach to Personality: Psychological Traits as Drivers and Consequences of Active Perception. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2021, 15, e12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, N.; Schultz, L. Neuroticism and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Prospective Investigation. Psychol. Med. 2012, 43, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruo, V.; Krauss, E.; Kleist, A.; Hardt, J.; Hake, K.; Peirano, J.; Krause, T.; Ehehalt, R.; von Arnauld de la Perriére, P.; Büning, J.; et al. Perceived distress, personality characteristics, coping strategies and psychosocial impairments in a national German multicenter cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Z. Gastroenterol. 2019, 57, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraaij, V.; Garnefski, N.; de Wilde, E.; Dijkstra, A.; Gebhardt, W.; Maes, S.; ter Doest, L. Negative Life Events and Depressive Symptoms in Late Adolescence: Bonding and Cognitive Coping as Vulnerability Factors? J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luteijn, F.; Starren, J.; Dijk, H. Handleiding Bij De NPV; Swets & Zeitlinger: Lisse, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bennebroek Evertsz’, F.; Nieuwkerk, P.; Stokkers, P.; Ponsioen, C.; Bockting, C.; Sanderman, R.; Sprangers, M. The Patient Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (P-SCCAI) Can Detect Ulcerative Colitis (UC) Disease Activity in Remission: A Comparison of The P-SCCAI with Clinician-Based SCCAI and Biological Markers. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Jiménez, I.; Nos, P.; Domènech, E.; Riestra, S.; Gisbert, J.; Calvet, X.; Cortés, X.; Iglesias, E.; Huguet, J.; Taxonera, C.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index Self-Administered Online at Home by Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: CRONICA-UC Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, A.; Ghosh, A.; Brain, A.; Buchel, O.; Burger, D.; Thomas, S.; White, L.; Collins, G.; Keshav, S.; Travis, S. Comparing Disease Activity Indices in Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennebroek Evertsz’, F.; Hoeks, C.; Nieuwkerk, P.; Stokkers, P.; Ponsioen, C.; Bockting, C.; Sanderman, R.; Sprangers, M. Development of the Patient Harvey Bradshaw Index and a Comparison with a Clinician-Based Harvey Bradshaw Index Assessment of Crohn’s Disease Activity. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 47, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, W. Predicting the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2006, 12, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeire, S.; Schreiber, S.; Sandborn, W.; Dubois, C.; Rutgeerts, P. Correlation between the Crohn’s Disease Activity and Harvey–Bradshaw Indices in Assessing Crohn’s Disease Severity. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, C.Y.; Morris, J.; Whorwell, P.J. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: A simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Mitchell, A.; Irvine, E.; Singer, J.; Williams, N.; Goodacre, R.; Tompkins, C. A New Measure of Health Status for Clinical Trials in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 1989, 96, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, D.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Carl, J.; Bullis, J.; Ellard, K. The Nature, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Neuroticism. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 2, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denovan, A.; Dagnall, N.; Lofthouse, G. Neuroticism and Somatic Complaints: Concomitant Effects of Rumination and Worry. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2018, 47, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, B.; Weiss, A.; Der, G.; Taylor, M.; Deary, I. Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Mortality in the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey: A 21-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Psychosom. Med. 2007, 69, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; López Blanco, B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Garrosa Hernández, E. The Influence of Personality Factors on Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 62, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J. Complex PTSD: A Syndrome In Survivors of Prolonged And Repeated Trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1992, 5, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erozkan, A. The link between types of attachment and childhood trauma. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.M.; Hicks, A.M.; Otter-Henderson, K. Physiological evidence for repressive coping among avoidantly attached adults. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 23, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, K.B. Attachment and psychoneuroimmunology. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019, 25, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouin, J.P.; Glaser, R.; Loving, T.J.; Malarkey, W.B.; Stowell, J.; Houts, C.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Attachment avoidance predicts inflammatory responses to marital conflict. Brain Behav. Immun. 2009, 23, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.G.; Hunter, J.J. Attachment and psychosomatic medicine: Developmental contributions to stress and disease. Psychosom. Med. 2001, 63, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; DeBuse, C.J.; Powers, S.I. Does Attachment Get Under the Skin? Adult Romantic Attachment and Cortisol Responses to Stress. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, A.; Rizzello, F.; Ravegnani, G.; Gionchetti, P.; Tambasco, R.; Straforini, G.; Ercolani, M.; Campieri, M. Adult attachment and early parental experiences in patients with Crohn’s disease. Psychosomatics. 2010, 51, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, A.; Moretti, M.; Calabrese, C.; Rizzello, F.; Gionchetti, P.; Ercolani, M.; Campieri, M. Attachment and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2014, 29, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, A.; Spuri Fornarini, G.; Ercolani, M.; Campieri, M. Attachment and perceived stress in patients with ulcerative colitis, a case-control study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 23, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelstrup, A.M.; Juillerat, P.; Korzenik, J. The accuracy of self-reported medical history: A preliminary analysis of the promise of internet-based research in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, H.; Kim, Y. Inflammation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 73, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease Activity Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quiescent (n = 84) | Mild (n = 65) | Moderate (n = 47) | Severe (n = 11) | |

| Trauma Type | Mean ± S.D. | Mean ± S.D. | Mean ± S.D. | Mean ± S.D. |

| Total trauma | 3.69 ± 3.17 | 4.52 ± 3.66 | 5.11 ± 3.72 | 7.18 ± 5.83 |

| Victimization | 0.48 ± 0.86 | 0.60 ± 1.14 | 0.64 ± 1.05 | 1.64 ± 2.50 |

| Neuroticism | 11.33 ± 7.91 | 16.52 ± 9.63 | 19.74 ± 8.16 | 24.36 ± 9.16 |

| n = 211 | IBS-SSS | IBD Activity | IBDQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total trauma | 0.112 | 0.173 * | −0.179 ** |

| Trauma profile 1 (medical disease relative) | −0.018 | 0.060 | 0.001 |

| Trauma profile 2 (psychopathology relative) | 0.042 | 0.055 | −0.068 |

| Trauma profile 3 (psychopathology self) | 0.099 | 0.160 * | −0.185 ** |

| Trauma profile 4 (victimization) | 0.165 * | 0.149 * | −0.219 *** |

| Neuroticism | 0.396 *** | 0.454 *** | −0.593 *** |

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | b | t | β | b | t | β |

| Trauma | 0.380 | 2.500 | 0.173 * | 0.114 | 0.793 | 0.052 |

| Neuroticism | 0.384 | 6.738 | 0.440 *** | |||

| R2 (ΔR2) | 0.030 * | 0.209 (0.179) ** | ||||

| F change | 6.252 * | 45.398 *** | ||||

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | b | t | β | b | t | β |

| Trauma | 3.769 | 1.623 | 0.112 | −0.119 | −0.053 | 0.958 |

| Neuroticism | 5.215 | 5.951 | 0.397 *** | |||

| R2 (ΔR2) | 0.013 | 0.157 (0.144) *** | ||||

| F change | 2.633 | 35.417 *** | ||||

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | b | t | β | b | t | β |

| Trauma | −1.720 | −2.636 | −0.179 ** | −0.088 | −0.157 | −0.009 |

| Neuroticism | −2.203 | −10.131 | −0.591 *** | |||

| R2 (ΔR2) | 0.032 ** | 0.352 (0.320) *** | ||||

| F change | 6.948 | 102.635 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nass, B.Y.S.; Dibbets, P.; Markus, C.R. The Impact of Psychotrauma and Emotional Stress Vulnerability on Physical and Mental Functioning of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216976

Nass BYS, Dibbets P, Markus CR. The Impact of Psychotrauma and Emotional Stress Vulnerability on Physical and Mental Functioning of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(21):6976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216976

Chicago/Turabian StyleNass, Boukje Yentl Sundari, Pauline Dibbets, and C. Rob Markus. 2023. "The Impact of Psychotrauma and Emotional Stress Vulnerability on Physical and Mental Functioning of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 21: 6976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216976

APA StyleNass, B. Y. S., Dibbets, P., & Markus, C. R. (2023). The Impact of Psychotrauma and Emotional Stress Vulnerability on Physical and Mental Functioning of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(21), 6976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216976