Promoting Women’s Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Protective Factors for Work–Family Conflict

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Work-Related Outcomes

1.2. Family-Related Outcomes

1.3. Domain-Unspecific Outcomes

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

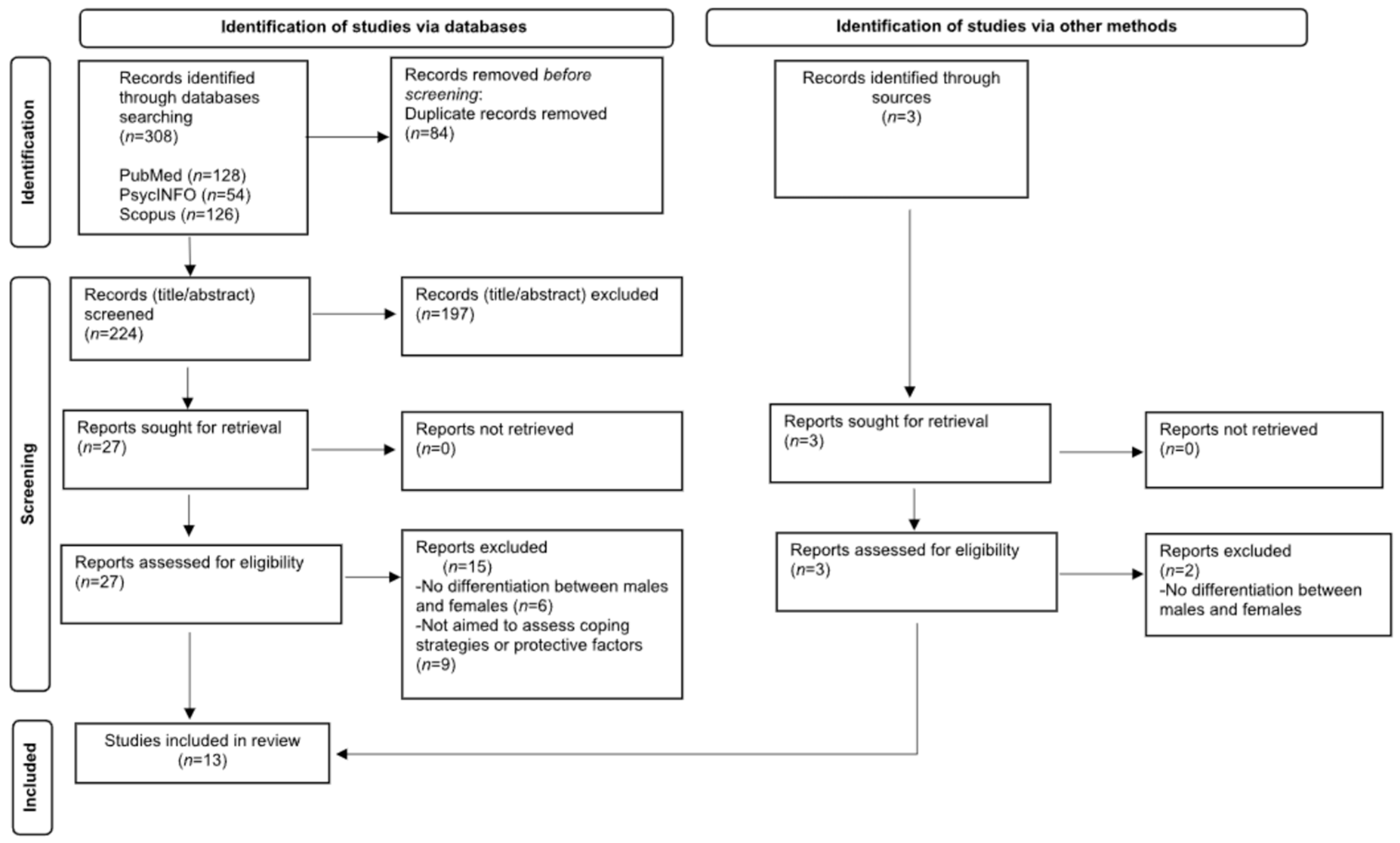

2.1. Search, Screening, and Selection Strategies

2.2. Coding

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Main Characteristics of the Selected Studies

3.2. Individual Protective Factors

3.3. Relational Protective Factors

3.4. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marks, S.R.; MacDermid, S.M. Multiple roles and the self: A theory of role balance. J. Marriage Fam. 1996, 58, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G. Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, L.; Shilo-Levin, S.; Liberman, G. Multiple roles, role satisfaction, and sense of meaning in life: An extended examination of role enrichment theory. J. Career Assess. 2015, 23, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.A.; Walsh, R.L.; Underwood, J.W. Experiences of School Counselor Mothers: A Phenomenological Investigation. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2018, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhan, J.H. Stress overload in the spread of coronavirus. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.; Ozeki, C. Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G. When Work And Family Are Allies: A Theory Of Work-Family Enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee, S.; Fields, D.; Luk, V. A cross-cultural test of a model of the work–family interface. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, F.M.; Frone, M.R. Work–family conflict. In Handbook of Work Stress; Barling, J., Kelloway, E.K., Frone, M.R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2005; pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, A.G.; Matthews, R.A.; Barnes-Farrell, J.L. Understanding the roles of subjective and objective aspects of time in the work-family interface. Community Work Fam. 2012, 15, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, K.A. Gender Differences and Similarities in Coping Responses to Anticipated Work-Family Conflict. Psychol. Rep. 1994, 74, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Lee, Y.; Lai, D.W.L. Mental Health of Employed Family Caregivers in Canada: A Gender-Based Analysis on the Role of Workplace Support. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2022, 95, 470–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinamon, R.G. Anticipated Work-Family Conflict: Effects of Gender, Self-Efficacy, and Family Background. Career Dev. Q. 2006, 54, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L.; Eddleston, K.A.; Veiga, J.F.J. Moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and career satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, L.M. Female Entrepreneurs, Work–Family Conflict, and Venture Performance: New Insights into the Work–Family Interface*. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starmer, A.J.; Frintner, M.P.; Matos, K.; Somberg, C.; Freed, G.; Byrne, B.J. Gender Discrepancies Related to Pediatrician Work-Life Balance and Household Responsibilities. Pediatrics 2019, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahaie, C.; Earle, A.; Heymann, J. An Uneven Burden:Social Disparities in Adult Caregiving Responsibilities, Working Conditions, and Caregiver Outcomes. Res. Aging 2013, 35, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian National Labour Inspectorate. Relazione Annuale Sulle Convalide Delle Dimissioni e Risoluzioni Consensuali Delle Lavoratrici Madri e Dei Lavoratori Padri ai Sensi Dell’art. 55 Del Decreto Legislativo 26 Marzo 2001. Italian National Labour Inspectorate: Rome, Italy, 2021. Available online: https://www.ispettorato.gov.it/files/2022/12/INL-RELAZIONE-CONVALIDE-DIMISSIONI-RISOLUZIONI-CONSENSUALI-2021.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Allen, T.D.; Herst, D.E.; Bruck, C.S.; Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Brashear-Alejandro, T.; Boles, J.S. A cross-national model of job-related outcomes of work role and family role variables: A retail sales context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Aisihaer, N.; Li, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Ren, S. Work-Family Conflict, Happiness and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Professional Women: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryee, S.; Srinivas, E.S.; Tan, H.H. Rhythms of life: Antecedents and outcomes of work-family balance in employed parents. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yucel, D. Job Autonomy and Schedule Flexibility as Moderators of the Relationship Between Work-Family Conflict and Work-Related Outcomes. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Kacmar, K.M. The relationship of schedule flexibility and outcomes via the work-family interface. J. Manag. Psychol. 2010, 25, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Ahmad, S.; Ullah, M.; Siddiq, A.; Ali, A.; Ali, N. Moderating Effect Of Work-Family Conflict On The Relationship Of Perceived Organizational Support And Job Satisfaction: A Study Of Government Commerce Colleges Of Kp, Pakistan. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 2282–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Isfianadewi, D.; Noordyani, A. Implementation of coping strategy in work-family conflict on job stress and job satisfaction: Social support as moderation variable. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2020, 9, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, M.C.W.; Montgomery, A.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Balancing Work and Home: How Job and Home Demands Are Related to Burnout. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recuero, L.H.; Segovia, A.O. Work-family conflict, coping strategies and burnout: A gender and couple analysis. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2021, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazami, S.; Shamsuddin, K.; Akmal, S. Examining Behavioural Coping Strategies as Mediators between Work-Family Conflict and Psychological Distress. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 343075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, E.; Bond, J.T.; Friedman, D.E. The Role of Employers in Addressing the Needs of Employed Parents. J. Soc. Issues 1996, 52, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, H.; O’Connell, P.J.; McGinnity, F. The Impact of Flexible Working Arrangements on Work–life Conflict and Work Pressure in Ireland. Gend. Work Organ. 2009, 16, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. Moderating effects of gender and family responsibilities on the relations between work–family policies and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1006–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cornejo, M.V. I Quit! Effects of Work-Family Policies on the Turnover Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, S.J.; Hill, E.J.; Yorgason, J.B.; Larson, J.H.; Sandberg, J.G. Couple Communication as a Mediator Between Work–Family Conflict and Marital Satisfaction. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2013, 35, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. Gender Role Ideology, Work–Family Conflict, Family–Work Conflict, and Marital Satisfaction Among Korean Dual-Earner Couples. J. Fam. Issues 2022, 43, 1520–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniarly, A.; Pratiwi, M.; Purnamasari, A.; Nadila, T.F. Work-family conflict, social support and marriage satisfaction on employees at bank x. J. Psikol. 2021, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, D.; Hamzah, H.; Abbas, N. Correlation Between Work-Family Conflict, Marital Satisfaction And Job Satisfaction. In Proceedings of the 8th UPI-UPSI International Conference 2018 (UPI-UPSI 2018), Bandung, Indonesia, 8 October 2019; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, J.M.; Matias, M.; Ferreira, T.; Lopez, F.G.; Matos, P.M. Parents’ work-family experiences and children’s problem behaviors: The mediating role of the parent–child relationship. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, V.; Power, K.G. Stress, satisfaction and role conflict in dual-doctor partnerships. Community Work Fam. 1999, 2, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Semmer, N.K. Spillover and crossover of work- and family-related negative emotions in couples. J. Psychol. Des Alltagshandelns 2011, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.Y.; Chen, X.; Cheung, F.M.; Liu, H.; Worthington, E.L. A dyadic model of the work-family interface: A study of dual-earner couples in China. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, D.S.; Perrewé, P.L. The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: An examination of work-family conflict. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahchai, R.; Fallahi, M.; Randall, A.K. A Dyadic Approach to Understanding Associations Between Job Stress, Marital Quality, and Dyadic Coping for Dual-Career Couples in Iran. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.K.; Wan, M.; Carlson, D.; Kacmar, K.M.; Thompson, M. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: A mega-meta path analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.-S.; Jeong, B.-Y. Structural Equation Model of Work Situation and Work–Family Conflict on Depression and Work Engagement in Commercial Motor Vehicle (CMV) Drivers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.T.; Barnes, C.M.; Scott, B.A. Driving it Home: How Workplace Emotional Labor Harms Employee Home Life. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, J.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Pulkkinen, L. Work–family conflict and psychological well-being: Stability and cross-lagged relations within one- and six-year follow-ups. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.C.W.; de Jonge, J.; Janssen, P.P.M.; van der Linden, S. Work-home interference, job stressors, and employee health in a longitudinal perspective. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2004, 11, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T. A model of coping with role conflict: The role behavior of college educated women. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, S.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Brough, P.; Kalliath, T.; Siu, O.-L.; Timms, C.; Riley, D.; Sit, C.; Lo, D. The relationship of social support with well-being outcomes via work–family conflict: Moderating effects of gender, dependants and nationality. Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 544–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Musisca, N.; Fleeson, W. Considering the role of personality in the work-family experience: Relationships of the big five to work-family conflict and facilitation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edura, W.; Rashid, W.E.W.; Nordin, M.S.; Omar, A.; Ismail, I. Evaluating Social Support, Work-Family Enrichment and Life Satisfaction among Nurses in Malaysia. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2011, 1, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M.; Fontaine, A.M. Coping with work and family: How do dual-earners interact? Scand. J. Psychol. 2015, 56, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranston Christopher, C.; Davis Joanne, L.; Rhudy Jamie, L.; Favorite Todd, K. Replication and Expansion of “Best Practice Guide for the Treatment of Nightmare Disorder in Adults”. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011, 07, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1-34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote; EndNote X8; Clarivate Analytics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aazami, S.; Akmal, S.; Shamsuddin, K. A model of work-family conflict and well-being among Malaysian working women. Work 2015, 52, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C.; Mikula, G. Work–Family Conflict and Perceived Justice as Mediators of Outcomes of Women’s Multiple Workload. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2014, 50, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chela-Alvarez, X.; Garcia-Buades, M.E.; Ferrer-Perez, V.A.; Bulilete, O.; Llobera, J. Work-family conflict among hotel housekeepers in the Balearic Islands (Spain). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0269074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Hawkes, S.L.; Kuipers, E.; Guest, D.; Fear, N.T.; Iversen, A.C. One year outcomes of a mentoring scheme for female academics: A pilot study at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London. BMC Med. Educ. 2011, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, M.; Ferreira, T.; Vieira, J.; Cadima, J.; Leal, T.; Mena Matos, P. Workplace Family Support, Parental Satisfaction, and Work–Family Conflict: Individual and Crossover Effects among Dual-Earner Couples. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somech, A.; Drach-Zahavy, A. Strategies for coping with work-family conflict: The distinctive relationships of gender role ideology. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, L. The Impact of Resources on Women’s Strategies for Coping With Work–Home Conflict: Does Sociocultural Context Matter? J. Fam. Soc. Work 2012, 15, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casale, S.; Banchi, V. Narcissism and problematic social media use: A systematic literature review. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 11, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musetti, A.; Manari, T.; Billieux, J.; Starcevic, V.; Schimmenti, A. Problematic social networking sites use and attachment: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannoy, S.; Duka, T.; Carbia, C.; Billieux, J.; Fontesse, S.; Dormal, V.; Gierski, F.; López-Caneda, E.; Sullivan, E.V.; Maurage, P. Emotional processes in binge drinking: A systematic review and perspective. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 84, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Gilmour, R.; Kao, S.F.; Huang, M.T. A cross-cultural study of work/family demands, work/family conflict and wellbeing: The Taiwanese vs British. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.L.; Millsteed, J.; Richmond, J.E.; Falkmer, M.; Falkmer, T.; Girdler, S.J. The impact of within and between role experiences on role balance outcomes for working Sandwich Generation Women. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rijk, A.E.; Blanc, P.M.L.; Schaufeli, W.B.; De Jonge, J. Active coping and need for control as moderators of the job demand–control model: Effects on burnout. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1998, 71, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Silbereisen, R.K. Coping with increased uncertainty in the field of work and family life. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2008, 15, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, D.; Danioni, F.; Benevene, P. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Role of Personal Values and Motivations for Teaching. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitlin, S.; Piliavin, J.A. Values: Reviving a Dormant Concept. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 359–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, S. Values, Personal Identity, and the Moral Self. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 515–529. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, C.; Barni, D.; Zagrean, I.; Danioni, F. Value Consistency across Relational Roles and Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Self-Concept Clarity. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, L.; Higgins, C. Interference between work and family: A status report on dual-career and dual-earner mothers and fathers. Empl. Assist. Q. 1994, 9, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Personality stability and its implications for clinical psychology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 6, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, S.E.; Goldberg, L.R. A first large cohort study of personality trait stability over the 40 years between elementary school and midlife. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.A.; Duxbury, L.E.; Irving, R.H. Work-family conflict in the dual-career family. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1992, 51, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Participants Characteristics | Fundings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aazami, S., Akmal, S., & Shamsuddin, K. [62] | 2015 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 567 women | Mage = 33.4 Mnumber of children = 1.7 Mwork hour = 42.9 | No |

| Aazami, S., Shamsuddin, K., & Akmal, S. [33] | 2015 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 429 women | Mage = 34.7 Mnumber of children = 1.7 Mwork hour = 42.7 | Yes |

| Andrade, C. & Mikula, G. [63] | 2014 | Austria Belgium Finland Germany Netherlands Portugal Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 1512 women | Mage = 35 Mnumber of children = 1.8 Mwork hour = 33 | Yes |

| Chela-Alvarez, X., Garcia-Buades, M.E., Ferrez-Pereira, V.A., Bulilete, O., & Llobera, J. [64] | 2023 | Balearic Islands | Cross-sectional | 1043 women | Mage = 43.3 Mwork hour = 47 | Yes |

| Drummond, S., O’Driscoll, M.P., Brough, P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O., Timms, C., Riley, D., Sit, C., & Lo, D. [54] | 2017 | Australia New Zealand China Hong Kong | Longitudinal (Two waves with a 12 month time lag) | 2183 total sample 1654 women | Total sample Mage = 36.33 | Yes |

| Dutta, R., Hawkes, S.L., Kuipers, E., Guest, D., Fear, N.T., & Iversen, A.C. [65] | 2011 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal (Three waves with a 6 month time lag) | 90 total sample 44 women | Not reported | No |

| Ho, M.Y., Chen, X., Cheung, F.M., Liu, H., & Worthington, E.L. [45] | 2013 | China | Cross-sectional | 306 total sample 153 women | Men Mage = 34.4 Women Mage = 32 Men Mwork hour = 48.7 Women Mwork hour = 44.7 | No |

| Matias, M., & Fontaine, A.M. [57] | 2015 | Portugal | Cross-sectional | 200 total sample 100 women | Total sample Mage = 36 Men Mwork hour = 61 Women Mwork hour = 57 | Yes |

| Matias, M., Ferreira, T., Vieira, J., Cadima, J., Leal, L., & Mena Matos, P. [66] | 2017 | Portugal | Longitudinal (Two waves with a 12 month time lag) | 180 total sample 90 women | Total sample Age range = 23 to 50 Total sample Mwork hour = 35 | Yes |

| Pan, Y., Aisihaer, A., Li, Q., Jiao, Y., & Ren, S. [25] | 2022 | China | Cross-sectional | 386 women | Mage = 31.39 | Yes |

| Recuero, L.H., & Segovia, A. [32] | 2021 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 262 total sample 161 women | Total sample Mage = 38.4 | No |

| Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. [67] | 2007 | Israel | Cross-sectional | 679 total sample 400 women | Total sample Mage = 37 | No |

| Kulik, L. [68] | 2012 | Israel | Cross-sectional | 146 women (59 Jewish, 87 Muslim Arab) | Jevish Mage = 36.5 Muslim Arab Mage = 35.2 Jevish Mnumber of children = 2.6 Muslim Arab Mnumber of children = 3.3 | No |

| Author(s) and Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 * | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | Q17 | Q18 | Q19 * | Q20 | Total Quality Score/20 | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aazami et al. [62] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 18 | High |

| Aazami et al. [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 17 | High |

| Andrade and Mikula [63] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | 16 | High |

| Chela-Alvarez et al. [64] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 17 | High |

| Drummond et al. [54] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | 16 | High |

| Dutta et al. [65] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 17 | High |

| Ho et al. [45] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 18 | High |

| Matias and Fontaine [57] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | 14 | Moderate |

| Matias et al. [66] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 16 | High |

| Pan et al. [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 18 | High |

| Recuero and Segovia [32] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | NR | 16 | High |

| Somech and Drach-Zahavy [67] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 17 | High |

| Kulik [68] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 16 | High |

| Mean | 16.62 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard Deviation | 1.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavagnis, L.; Russo, C.; Danioni, F.; Barni, D. Promoting Women’s Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Protective Factors for Work–Family Conflict. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216992

Cavagnis L, Russo C, Danioni F, Barni D. Promoting Women’s Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Protective Factors for Work–Family Conflict. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(21):6992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216992

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavagnis, Lucrezia, Claudia Russo, Francesca Danioni, and Daniela Barni. 2023. "Promoting Women’s Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Protective Factors for Work–Family Conflict" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 21: 6992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216992

APA StyleCavagnis, L., Russo, C., Danioni, F., & Barni, D. (2023). Promoting Women’s Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Protective Factors for Work–Family Conflict. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(21), 6992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216992