Suitability of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire Short Form for Use among Adults in Their 50s: A Cross-Sectional e-Survey Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

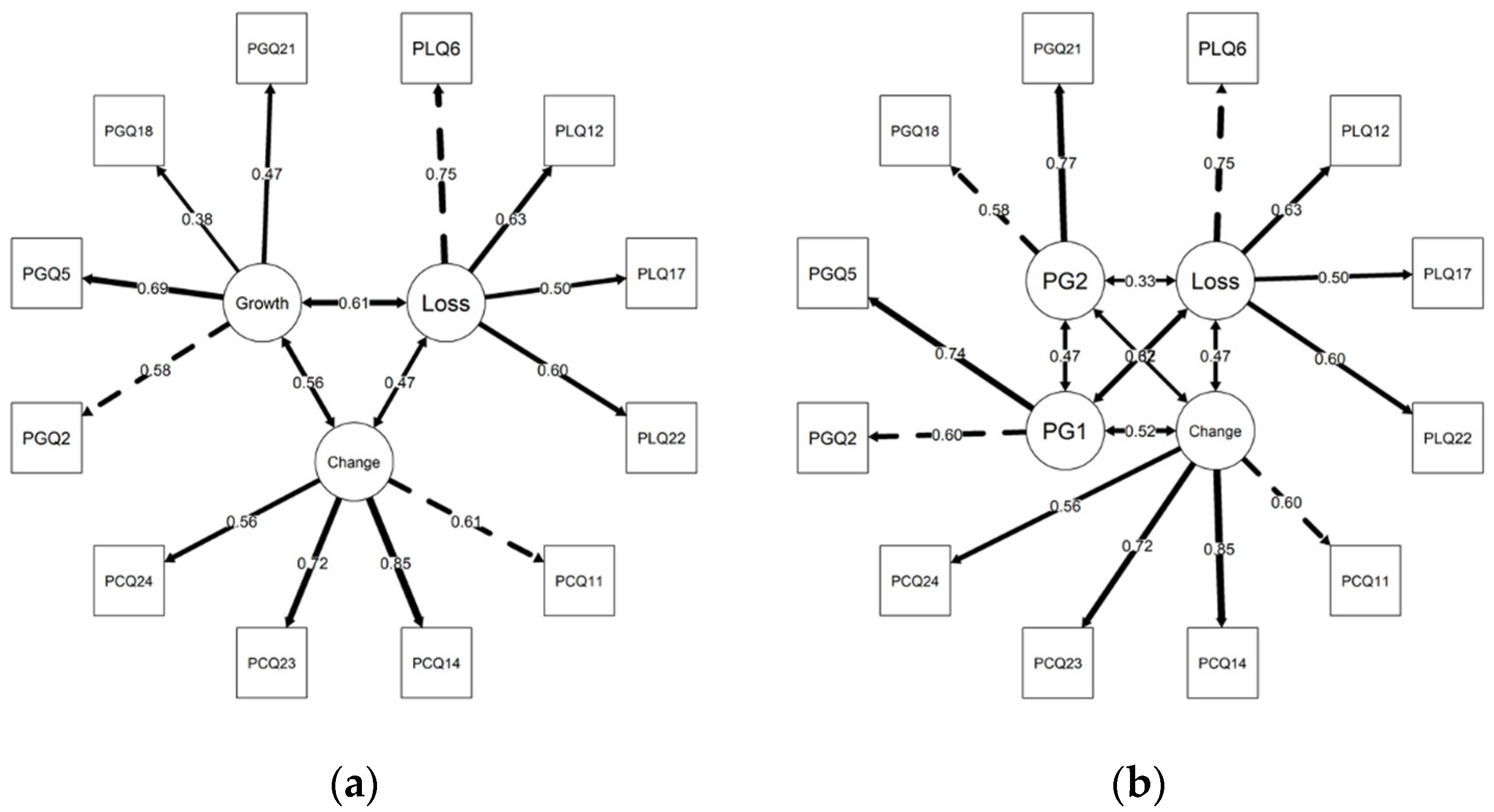

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Dr. Gail Low, Associate Professor, University of Alberta, Faculty of Nursing

- Dr. Donna Wilson, Professor, University of Alberta, Faculty of Nursing

- Dr. Gloria Gutman, Professor, Simon Fraser University, Department of Gerontology

- Dr. Michael Stones, Professor, Lakehead University, Department of Psychology

References

- Laidlaw, K.; Kishita, N.; Shenkin, S.; Power, M.J. Development of a short form of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire (AAQ). Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, K.; Power, M.J.; The WHOQOL-OLD Group. The Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire (AAQ): Development and psychometric properties. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life; WHO Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Use: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marquet, M.; Missotten, P.; Schroyen, S.; van Smabeek, I.; van den Akker, M.; van den Broeke, C.; Buntinx, F.; Stéphane, A. A Validation of the French Version of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire (AAQ): Factor structure, reliability and validity. Psychol. Belg. 2016, 56, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas-Carrasco, R.; Laidlaw, K.; Gomez-Benito, J.; Power, M. The suitability of the Attitudes Ageing (AAQ) for Spanish older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorius, N.; Kuyken, W. Translation of health status instruments. In Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives; Orley, J., Kuyken, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-3-642-79125-3. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Bryant, C.; Brown, V.; Bei, B.; Judd, F. Self-compassion, attitudes to ageing and indicators of health and well-being among midlife women. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachamovic, E.; Fleck, M.P.; Trentini, C.M.; Laidlaw, K.; Power, M.J. Development and validation of the Brazilian version of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire (AAQ): An example of merging classical psychometric theory and the Rasch measurement model. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, G.; Molzahn, A.; Schopflocher, D. Attitudes to aging mediate the relationship between older peoples’ subjective health and quality of life in 20 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E. Mind the gap in the middle: A call to study midlife. Res. Hum. Dev. 2015, 12, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E.; Teshale, S.; Agrigoroaei, S. Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the cross-roads of youth and old age. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montepare, J.M. Subjective age: Toward a guiding lifespan framework. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Wurm, S. Longitudinal research on subjective aging, health, and longevity: Current evidence and new directions for research. Ann. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 35, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbourne, S.K.; Sneed, J. The paradox of well-being, identity processes, and stereotype threat: Ageism and its potential relationships with the self in later life. In Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice against Older Persons; Nelson, T.D., Ed.; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 247–273. ISBN 0-262-14077-2. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen, V. Beyond Successful Aging and Active Ageing: A Theory of Model Ageing; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4473-3017-2. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Chang, E.S.; Kannoth, S.; Wang, S.Y. Ageism Amplifies Cost and Prevalence of Health Conditions. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.S.; Kannoth, S.; Levy, S.; Wang, S.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Levy, B.R. Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0220857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodner, E.; Ayalon, L.; Avidor, S.; Palgi, Y. Accelerated increase and relative decrease in subjective age and changes in attitudes toward own aging over a 4-year period: Results from the Health and Retirement Study. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, D. Resilience, life events, and well-being during midlife: Examining resilience subgroups. J. Adult Dev. 2018, 25, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.; Kunzman, U. Longitudinal changes in subjective social status are linked to changes in positive and negative affect in midlife, but not in later adulthood. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Do Humans Suffer a Psychological Low in Midlife? Two Approaches (with and without Controls) in Seven Data Sets. 2017. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3029829 (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Kornadt, A.E.; Voss, P.; Rothermund, K. Age stereotypes and self-views revisited: Patterns of internalization and projection across the life span. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Wahl, H.W.; Siebert, J.S. 20-year trajectories of health in midlife and old age: Contrasting the impact of personality and attitudes toward own aging. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornadt, A.E.; Kessler, E.-M.; Wurm, S.; Bowen, C.E.; Gabrian, M.; Klusmann, V. Views on ageing: A lifespan perspective. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Association of Retired Persons. CARP Member Profile Poll Report. 2017. Available online: https://carp-20230727.s3.amazonaws.com/2015/08/CARP-Member-Profile-Poll-Report-AUG-2015.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2017).

- Zoomer Media. 2019. Media Kit. Available online: https://www.zoomermedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Zoomer-Radio-MEDIA-KIT-SUMMER-2020.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Zoomer Media. 2020. Media Kit 2020. Available online: https://www.zoomermedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Zoomer-Radio-MEDIA-KIT-SUMMER-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- SurveyMonkey Inc. Who Is Your Survey Audience? 1999–2023. San Mateo, California, USA. Available online: www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- University of Maryland Department of Sociology. Using. Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale. 2018. Available online: https://socy.umd.edu/about-us/rosenberg-self-esteem-scale (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency information. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. Reliability of tests: Practical issues. In Handbook of Psychological Testing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 7–16. ISBN 978-1-3158-1227-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variable and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Yves Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for structural equation modeling. J Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y.; Miller, P.; Quick, C.; Garnier-Villarreal, M.; Selig, J.; Boulton, A.; Preacher, K.; et al. semTools: Useful Tools For Structural Equation Modeling, R Package Version 0.5-1; 2018. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Flora, D.B.; Curran, P.J. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Meth. 2004, 9, 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhemtulla, M.; Brosseau-Liard, P.E.; Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Meth. 2012, 17, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. SEM: Confirmatory factor analysis. Structural equation modeling. In Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Andover, UK, 2019; pp. 658–698. ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Multivariate Application Series; Lawrence-Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-8058-3322-6. [Google Scholar]

- Asún, R.A.; Rdz-Navarro, K.; Alvarado, J.M. Developing multidimensional likert scales using item factor analysis: The case of four-point items. Sociol. Method. Res. 2016, 45, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado-Tello, F.P.; Chacón-Moscoso, S.; Barbero-García, I.; Vila-Abad, E. Polychoric versus Pearson correlations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Thompson, B.; Wang, L. Effects of sample size, estimation methods, and model specification on structure modeling fit indexes. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Structural equation modeling: An introduction. In Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Andover, UK, 2019; pp. 603–657. ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment. on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers of overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2015, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E. CFI versus RMSEA: A comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 1996, 3, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Multivariate Application Series; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 0-8058-6373-7. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, T.G.; Morrison, M.; McCutcheon, J.M. Best practice recommendations for using structural equation modelling in psychological research. Psychology 2017, 8, 1326–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, G.; Ross, C.; Stickland, M.; Wilson, D.; Wong, E. Attitudes to ageing among older people with COPD. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 35, 884–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, A.M.; Pearson, J.F.; Schluter, P.J.; Spittlehouse, J.K.; Joyce, P.R. Attitudes to aging in midlife are related to health conditions and mood. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.M.; Dow, B.; Moore, K.; Hill, K.; Russell, M.; Cyrato, E.; Malta, S.; Ames, D.; Lautenschlager, N.T. Attitudes to aging in older carers—Do they have a role in their well-being? Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M. Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 81, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D. 2006–2023. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Chen, S.Y.; Feng, Z.; Yi, X. A general introduction to adjustment for multiple comparisons. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzus, C.; Zimmermann, J.; Mund, M.; Neyer, F.J. Friendships in young and middle adulthood: Normative patterns and personality differences. In Psychology of Friendship; Hojjat, M., Moyer, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-1902-2202-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Turan, B.; Scheibe, S.; Ram, N.; Ersner-Hershfield, H.; Samanez-Larkin, G.R.; Brooks, K.P.; Nesselroade, J.R. Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychol. Aging 2011, 26, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Chan, L.; Mikels, J.A. Meta-analysis of the age-related positivity effect: Age differences in preferences for positive over negative information. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blieszner, R.; Ogeltree, A.M.; Adams, R.G. Friendships in later life: A research agenda. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, igz005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, E. The moderating effects of age on the relationships of self-compassion, self-esteem, and mental health. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2016, 58, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelt, M.; Jeste, D.V. Wisdom and hard times: The ameliorating effect of wisdom on the negative association between adverse life events and well-being. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.G. The Problem with Over-Relying on Quantitative Evidence of Validity. Dissertation Chapter, University of California, Santa Barbara, 8 December 2022. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/v4nb2/download?format=pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Helmes, E.; Pachana, N.A. Dimensions of stereotypical attitudes among older adults: Analysis of two countries. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2016, 16, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.C.; Powdthavee, N.; Oswald, A.J. Longitudinal evidence for a midlife nadir: Result from four data sets. Econ. J. 2017, 127, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galambos, N.L.; Krahn, H.J.; Johnson, M.D.; Lachman, M.E. The U shape of happiness across the life course: Expanding the discussion. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindwall, M.; Barkoukis, V.; Grano, C.; Lucidi, F.; Raudsepp, L.; Liukkonen, J.; ThØrsgersen-Ntoumani, C. Method effects: The problem with negatively versus positively keyed items. J. Pers. Assess. 2012, 94, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, S.P.; Gothe, N.P.; McAuley, E. Evaluation of the factor structure of the Rosenberg Self-Esteen Scale in older adults. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.J.; Yang, C.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Lee, M.C. Psychometric Properties of a Taiwanese Attitude toward Aging Questionnaire-Short Form Used in the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging. Int. J. Gerontol. 2022, 16, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueber, D.M.; Toland, M.D.; Lingat, J.E.; Love, A.M.A.; Qiu, C.; Wu, R.; Brown, A.V. To reverse item orientation or not to reverse item orientation, that is the question. Assessment 2022, 29, 1422–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayordomo, T.; Gutierrez, M.; Sales, A. Adapting and validating the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale for elderly Spanish population. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seattle Quality of Life Group. More Instrument Information. 2011. Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/seaqol/WHOQOL-BREF (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2764404 (accessed on 31 May 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Guidance: Operational Considerations for Multi Sectoral Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Programmes during COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-reference-group-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings/iasc-guidance-operational-considerations-multisectoral-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Gutman, G.; de Vries, B.; Beringer, R.; Daudt, H.; Gill, P. COVID-19 Experiences & Advance Care Planning (ACP) among Older Canadians: Influence of Age Group, Gender, & Sexual Orientation. 2021. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/lgbteol (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Mukhtar, S. Psychological health during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, P.; Wolfson, C.; Griffith, L.; Kirkland, S.; McMillan, J.; Basta, N.; Joshi, D.; Oz, U.E.; Sohel, N.; Maimon, G.; et al. A longitudinal analysis of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. NPJ Aging 2021, 1, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. The Contribution of Pandemic Relief Benefits to the Incomes of Canadians in 2020. 2022. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021005/98-200-X2021005-eng.cfm (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Iftene, F.; Milev, R.; Farcas, A.; Squires, S.; Smirnova, D.; Fountoulakis, K.N. COVID-19 Pandemic: The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Life Habits in the Canadian Population. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, e871119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongou, R.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Maltais, S.; Mabeu, M.C.; Agarwal, A.; Yaya, S. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. PloS ONE 2022, 17, e0277238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callow, D.C.; Arnold-Nedimala, N.A.; Jordan, L.S.; Pena, G.S.; Won, J.; Woodard, J.L.; Carson Smith, J. The mental health benefits of physical activity in older adults survive the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingtier, J.A.; Neupert, S.D. Negative attitudes predict greater reactivity to daily stressors in older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Global Natural Experiment. Circulation 2020, 142, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Mental Health Association. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Mental Health: Heading off an Echo Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/EN_COVID-19-Policy-Brief.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Ayalon, L.; Chasteen, A.; Diehl, M.; Levy, B.R.; Neupert, S.D.; Rothermund, K.; Tesh-Römer, C.; Wahl, H.W. Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e49–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornadt, A.; Albert, I.; Hoffmann, M.; Murdock, E.; Nell, J. Perceived ageism during the COVID-19-crisis is longitudinally related to subjective perceptions of aging. Front. Public. Health 2021, 9, 679711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomann, A.; Bünning, M.; Hipp, L.; Wahl, H. Aging during COVID-19 in Germany: A longitudinal analysis of psychosocial adaptation and attitudes toward aging. Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, S.; Turner, S.; Brooker, H.; Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Hampshire, A. Physical and mental health conditions account for variability in awareness of age-related changes. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1152177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Post-COVID Condition (Long COVID). 2023. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/symptoms/post-covid-19-condition.html (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Hobfoll, S.; Watson, P.; Bell, C.C.; Bryant, R.A.; Brymer, M.J.; Friedman, M.J.; Friedman, M.; Gersons, B.P.R.; de Jong, J.T.V.M.; Layne, C.M.; et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry 2007, 70, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, P.; AboJabel, H. The conceptual and methodological characteristics of ageism during COVID-19: A scoping review of empirical studies. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2821%2902143-7 (accessed on 30 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Humboldt, S.; Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N.; Arias-Merino, E.; Ribeiro-Gonçalves, J.A.; Cabras, E.; Low, G.; Leal, I.P. The upside of negative emotions: How do older adults from different cultures challenge their self-growth during the COVID-19 pandemic? Front. Psychology 2022, 13, e648078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Reference Bureau. The Best Years of Their Lives? Young Adults Reported More Anxiety than Older Adults during Pandemic, Despite Lower Health Risks. 2023. Available online: https://www.prb.org/resources/the-best-years-of-their-lives-young-adults-reported-more-anxiety-than-older-adults-during-pandemic-despite-lower-health-risks/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Moyser, M. Gender Differences in Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/statcan/45-28/CS45-28-1-2020-44-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Rejeh, N.; Haravi-Karimooi, M.; Vaismoradi, M.; Griffiths, P.; Nikkhah, M.; Bahrami, T. Psychometric properties of the Farsi version of Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire in Iranian older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckinx, F.; Charles, A.; Rygaert, X.; Reginster, J.Y.; Adam, S.; Bruyère, O. Own attitude toward aging among nursing home residents: Results of the SENIOR cohort. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, G.; Kartal, A.; Çinar, I.O.; Koştu, N. The relationship between attitudes toward aging and health-promoting behaviors in older adults. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2016, 2, e12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, R.; Roberts, K.J. Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research—Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Saver, U. SOLOMON: A method for splitting a sample into equivalent subsamples in factor analysis. Behav. Res. Meth. 2022, 54, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AAQ-SF Subscale | M (SD) | Skew | Kurtosis | r | ω [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Change (PC) | 13.45 (3.46) | −0.235 | −0.262 | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | |

| I don’t feel old | 3.79 (1.05) | −0.695 | −0.075 | 0.692 | |

| I have more energy now than I expected for my age | 3.03 (1.11) | 0.117 | −0.934 | 0.831 | |

| My health is better than expected for my age | 3.19 (1.12) | −0.230 | −0.679 | 0.822 | |

| I meep myself as fit and active as possible by exercising | 3.44 (1.18) | −0.466 | −0.654 | 0.745 | |

| Psychosocial Loss (PL) | 14.42 (3.07) | −0.349 | 0.064 | 0.71 (0.68–0.76) | |

| Old age is a depressing time of life | 3.48 (0.99) | −0.16 | −0.65 | 0.750 | |

| I see old age mainly as a time of loss | 3.70 (1.01) | −0.62 | −0.01 | 0.717 | |

| As I get older, I find it more difficult to make new friends | 3.57 (1.09) | −0.63 | −0.26 | 0.725 | |

| I feel excluded from things because of my age | 3.67 (1.06) | −0.67 | −0.09 | 0.756 | |

| Psychological Growth (PG) | 15.23 (2.49) | −0.514 | 1.40 | 0.61 (0.57–0.67) | |

| It is a privilege to grow old | 3.90 (0.935) | −0.945 | 0.664 | 0.727 | |

| There are many pleasant things about growing older | 3.74 (0.857) | −0.920 | 1.068 | 0.667 | |

| It is very important to pass on the benefits of my experiences to younger people | 3.58 (0.919) | −0.362 | 0.013 | 0.664 | |

| I want to give a good example to younger people | 4.00 (0.831) | −0.944 | 1.334 | 0.685 |

| Model | X2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [90% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Subscale Growth | 159.89 | 51 | 0.980 | 0.974 | 0.039 [0.025–0.052] |

| Two-Subscale Growth | 116.14 | 48 | 0.927 | 0.900 | 0.05 [0.04–0.065] |

| AAQ-SF Subscale | M (SD) | M (SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 108) | Women (n = 409) | ||

| Physical Change | 13.68 (3.63) | 13.39 (3.41) | −0.774 |

| Psychosocial Loss | 14.86 (2.94) | 14.31 (3.10) | −1.69 |

| Psychological Growth | 15.39 (2.91) | 15.19 (2.37) | −0.736 |

| Post-secondary (n = 419) | No Post-secondary (n = 98) | ||

| Physical Change | 13.60 (3.42) | 12.78 (3.58) | −2.11 |

| Psychosocial Loss | 14.35 (3.07) | 14.68 (3.08) | 0.951 |

| Psychological Growth | 15.29 (2.37) | 14.98 (2.93) | −1.12 |

| Married/Partnered (n = 345) | Alone (n = 172) | ||

| Physical Change | 13.61 (3.45) | 13.12 (3.45) | −6.55 *** |

| Psychosocial Loss | 14.65 (2.88) | 13.95 (3.40) | −3.49 ** |

| Psychological Growth | 15.35 (2.56) | 14.99 (2.32) | 1.18 |

| Has comorbidities (n = 243) | No comorbidities (n = 268) | ||

| Physical Change | 12.55 (3.34) | 14.43 (3.13) | −6.55 *** |

| Psychosocial Loss | 13.97 (2.98) | 14.89 (3.00) | −3.49 ** |

| Psychological Growth | 15.15 (2.50) | 15.40 (2.33) | −1.18 |

| Fair/Poor (n = 51) | Good to Excellent (n = 466) | ||

| Physical Change | 8.90 (2.71) | 13.94 (3.16) | −10.97 *** |

| Psychosocial Loss | 12.41 (3.59) | 14.64 (2.93) | −5.02 *** |

| Psychological Growth | 13.76 (2.78) | 15.39 (2.40) | −4.52 *** |

| Model | X2 | Df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [90% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Subscale Growth | 454.12 | 205 | 0.866 | 0.849 | 0.049 [0.043–0.055] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Low, G.; França, A.B.; Wilson, D.M.; Gutman, G.; von Humboldt, S. Suitability of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire Short Form for Use among Adults in Their 50s: A Cross-Sectional e-Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227035

Low G, França AB, Wilson DM, Gutman G, von Humboldt S. Suitability of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire Short Form for Use among Adults in Their 50s: A Cross-Sectional e-Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(22):7035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227035

Chicago/Turabian StyleLow, Gail, Alex Bacadini França, Donna M. Wilson, Gloria Gutman, and Sofia von Humboldt. 2023. "Suitability of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire Short Form for Use among Adults in Their 50s: A Cross-Sectional e-Survey Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 22: 7035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227035

APA StyleLow, G., França, A. B., Wilson, D. M., Gutman, G., & von Humboldt, S. (2023). Suitability of the Attitudes to Aging Questionnaire Short Form for Use among Adults in Their 50s: A Cross-Sectional e-Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(22), 7035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227035