Exploring Rehabilitation Provider Experiences of Providing Health Services for People Living with Long COVID in Alberta

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Question Guide Development

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

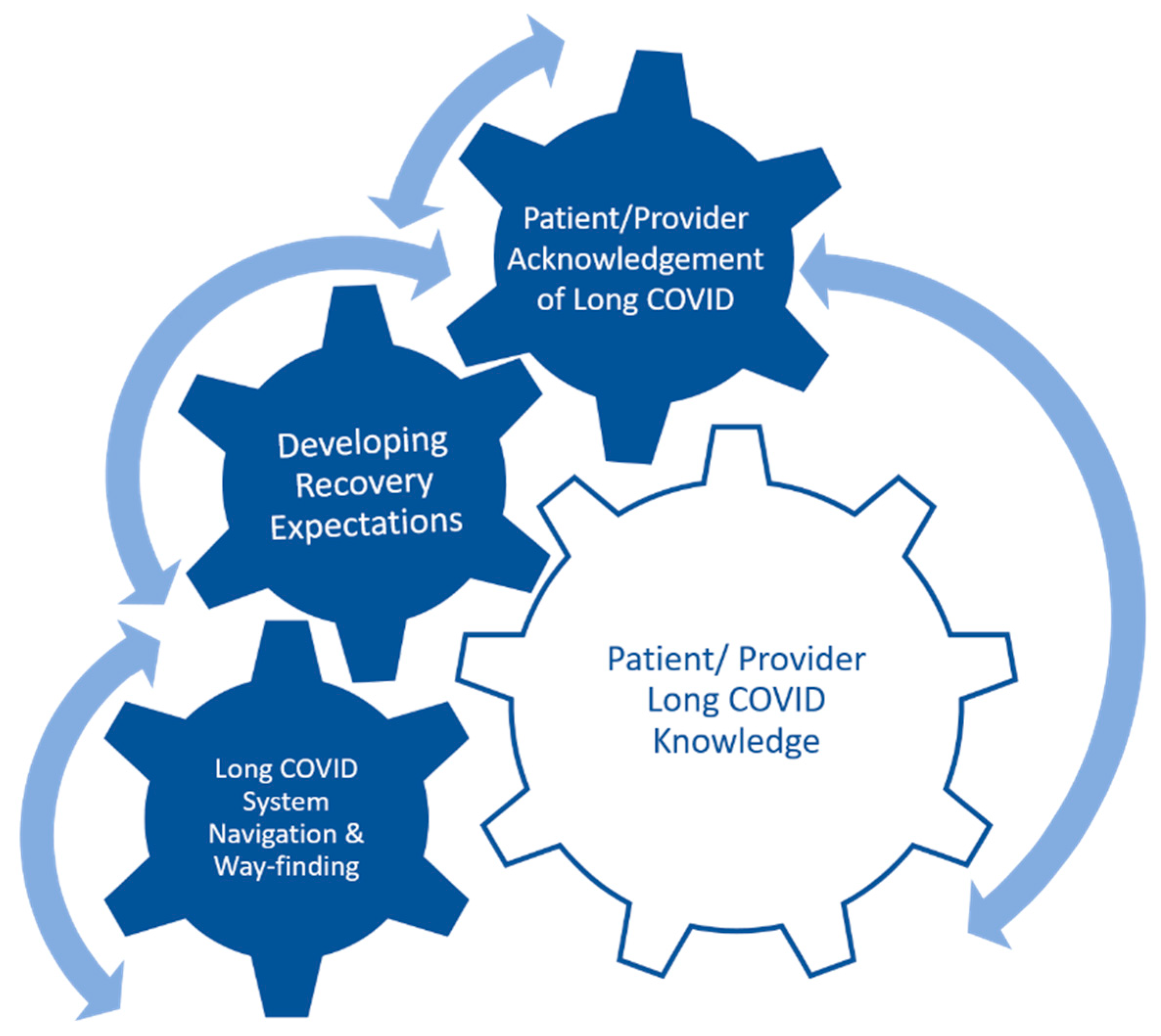

3. Results

3.1. Importance of Patient/Provider Knowledge for Long COVID Recognition

When we had all our education on this, that wasn’t really part of the education… searching for long COVID.(Primary care provider—Interview 8)

(Patients) are not getting the support from anywhere else; a lot of them are really shocked when they talk to their GPs (primary care physician) and the GP isn’t aware that [specialty clinic] is here.(Rehabilitation care provider—Interview 1)

When I was reading… (experts) were talking about 200 symptoms of long COVID, I don’t know all 200 symptoms. That just blew me away… oh my gosh, we don’t ask 200 symptoms on our (long COVID) questionnaire.(Rehabilitation care provider—Interview 1)

Some of the patients that do come to us, they tell us that they read about a case in the newspaper and then they went and told their doctor.(Specialty care provider—Interview 6)

My clinical assessments have certainly evolved since being in this since January. Just asking more questions, being more astute… in the long COVID world, it’s things that they’re saying and it’s like let’s move over there and talk about that. So, I think that’s just me evolving in my assessment skills.(Specialty care provider—Interview 9)

3.2. The Role of Patient/Provider Acknowledgement of Long COVID

3.2.1. Disbelief in COVID or Long COVID

(Patients) are not getting the support from anywhere else. (I) Just feel that a lot of our (patients), especially the long-haul ones, what we’re calling long COVID, when they’re 12, 14, 16 weeks out. They’re just finding there’s not a lot of buy-in, from friends, from family, from employers… We’re finding there’s not a lot of buy-in from even our medical community, right now.(Rehabilitation care provider—Interview 1)

“It’s not the patient’s fault because they don’t know what’s available to them… And when they do ask for help, I have heard ‘my physician doesn’t believe me, they don’t believe in COVID, they don’t believe I’m experiencing these symptoms, and they don’t know where to send me if I’m experiencing these symptoms’”.(Specialty care provider—Interview 6)

3.2.2. Acknowledgement as Part of Care

“I think another advantage (of long COVID care) is, the patients feel supported and that they’re not losing their mind, and it’s all in their head. They’re like… I still feel (bad) and nobody knows, we don’t know ‘cause this is new. So I think that’s a big plus, a big advantage for the patients to feel that, just feel supported”.(Primary care provider—Interview 8)

“I think the support piece has been really big (at our site) and that’s what we hear in feedback is just how grateful they are that somebody is here to listen and believes them”.(Rehabilitation care provider—Interview 1)

“Most of my patients have talked to… their primary care provider about their symptoms and they’re told that long COVID is a problem and… they could be experiencing those symptoms, but that… seems to be where the conversation ends. … primarily patients… are saying that… they talked to their provider about their symptoms, but they don’t know what else to do. … And (are) not provided with those additional resources”.(Specialty care provider—Interview 7)

3.3. Developing Recovery Expectations

“I can only think of one (patient) in particular off the top of my head that did not find the resources helpful, and she was really looking for much more specific (steps)… Some conversation… and some understanding of really what’s appropriate for treatment was helpful for her”.(Specialty care provider—Interview 7)

“I impart on my patients that I don’t have a pill that I can give you that’s going to get rid of your post COVID symptoms. I have some medications that can help manage some of the symptoms that you may experiencing, but overall, you’ve got to put in the work, I’ll put in the work with you, but you’ve got to put in the work yourself and here are the tools I’m handing to you”.(Specialty care provider—Interview 6)

3.4. Navigation and Wayfinding

3.4.1. Poor Integration with Social and Mental Health Services

“I would love for us to have… some kind of mental health resource—so either a psychologist or a psychiatrist to refer our patients to because a lot of our patients have mental health needs that were either borderline or nonexistent before COVID, and after their COVID illness have significantly impacted them. And so, when we get one of those, where do you go from here?”(Specialty care provider—Interview 6)

3.4.2. Wait Times/Referrals

“Some of those people who don’t connect with a family doctor, fall through the cracks. It delays referrals—that kind of thing, and potentially leads to duplication. So I think that’s an issue, is maybe needing that referral from the family doc for people who don’t have it”.(Rehabilitation care provider—Interview 2)

“I would say there’s potential (for patients to access long COVID health services), but I think the wait list is so long and depending on people’s needs, like in a timely manner I would say no… and that is certainly a challenge for us, is it’s just backlogged”.(Rehabilitation care provider—Interview 2)

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions and Future Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. The Daily—Between April and August 2022, 98% of Canadians Had Antibodies against COVID-19 and 54% Had Antibodies from a Previous Infection (No. No. 11-001–X). 2023. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230327/dq230327b-eng.htm (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Miranda, D.A.P.d.; Gomes, S.V.C.; Filgueiras, P.S.; Corsini, C.A.; Almeida, N.B.F.; Silva, R.A.; Medeiros, M.I.V.A.R.C.; Vilela, R.V.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Grenfell, R.F.Q. Long COVID-19 syndrome: A 14-months longitudinal study during the two first epidemic peaks in Southeast Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, A.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Wootton, D.; Crooks, M.; Gabbay, M.; Eichert, N.; Mouchti, S.; Pansini, M.; Roca-Fernandez, A.; Thomaides-Brears, H.; et al. Multi-organ impairment and long COVID: A 1-year prospective, longitudinal cohort study. J. R. Soc. Med. 2023, 116, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, B.; Sudry, T.; Flaks-Manov, N.; Yehezkelli, Y.; Kalkstein, N.; Akiva, P.; Ekka-Zohar, A.; Ben David, S.S.; Lerner, U.; Bivas-Benita, M.; et al. Long COVID outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2023, 380, e072529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouz, T.; Menges, D.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Domenghino, A.; Aschmann, H.; Frei, A.; Fehr, J.S.; Puhan, A.M. Recovery and symptom trajectories up to two years after SARS-CoV-2 infection: Population based, longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2023, 381, e074425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; O’Brien, K.K. Conceptualising Long COVID as an episodic health condition. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e007004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-Andon, T.; Walsh, S.; Berger-Gillam, T.; Pari, A.A.A. Systematic review of post-COVID-19 syndrome rehabilitation guidelines. Integr. Health J. 2023, 444, e000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’Em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and Predictors of Long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houben-Wilke, S.; Goërtz, Y.M.; Delbressine, J.M.; Vaes, A.W.; Meys, R.; Machado, F.V.; van Herck, M.; Burtin, C.; Posthuma, R.; Franssen, F.M.; et al. The Impact of Long COVID-19 on Mental Health: Observational 6-Month Follow-Up Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e33704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berentschot, J.C.; Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H.; Bek, L.M.; Huijts, S.M.; van Bommel, J.; van Genderen, M.E.; Aerts, J.G.; Ribbers, G.M.; Hellemons, M.E.; Berg-Emons, R.J.v.D.; et al. Physical recovery across care pathways up to 12 months after hospitalization for COVID-19: A multicenter prospective cohort study (CO-FLOW). Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 22, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daynes, E.; Gerlis, C.; Chaplin, E.; Gardiner, N.; Singh, S.J. Early experiences of rehabilitation for individuals post-COVID to improve fatigue, breathlessness exercise capacity and cognition—A cohort study. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2021, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, F.; Palatulan, E.; Jaywant, A.; Said, R.; Lau, C.; Sood, V.; Layton, A.; Gellhorn, A. Outcomes of a COVID-19 recovery program for patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 infection in New York City: A prospective cohort study. PMR J. Inj. Funct. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimeno-Almazán, A.; Franco-López, F.; Buendía-Romero, A.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Sánchez-Agar, J.A.; Martínez, B.J.S.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Pallarés, J.G. Rehabilitation for post-COVID-19 condition through a supervised exercise intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 1791–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, T.; Anaya, Y.B.; Shih, K.J.; Tarn, D.M. A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Physicians’ Experiences with Telemedicine During COVID-19. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, S61–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysa, J.A.; Buell, M.; Manhas, K.P.; Burns, K.K.; Santana, M.J.; Horlick, S.; Russell, K.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Ho, C. Understanding the Experience of Long COVID Symptoms in Hospitalized and Non-Hospitalized Individuals: A Random, Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhas, K.P.; O’connell, P.; Krysa, J.; Henderson, I.; Ho, C.; Papathanassoglou, E. Development of a Novel Care Rehabilitation Pathway for Post-COVID Conditions (Long COVID) in a Provincial Health System in Alberta, Canada. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzac090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review. Res. Nurs. Health 2016, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2009, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, J.; Oberle, K. Enhancing Rigor in Qualitative Description: A case study. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2005, 32, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyngäs, H. Inductive Content Analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireson, J.; Taylor, A.; Richardson, E.; Greenfield, B.; Jones, G. Exploring invisibility and epistemic injustice in Long COVID—A citizen science qualitative analysis of patient stories from an online COVID community. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 1753–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, C.; Ladds, E.; Husain, L.; Pattinson, K.; Greenhalgh, T. ‘I can’t cope with multiple inputs’: A qualitative study of the lived experience of ‘brain fog’ after COVID-19. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingstone, T.; Taylor, A.K.; O’Donnell, C.; Atherton, H.; Blane, D.N.; A Chew-Graham, C. Finding the ‘right’ GP: A qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID. BJGP Open 2020, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladds, E.; Rushforth, A.; Wieringa, S.; Taylor, S.; Rayner, C.; Husain, L.; Greenhalgh, T. Developing services for long COVID: Lessons from a study of wounded healers. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.; Spence, N.J.; Chase, J.-A.D.; Schwartz, T.; Tumminello, C.M.; Bouldin, E. Support amid uncertainty: Long COVID illness experiences and the role of online communities. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Kudla, A.; Pham, T.; Ezeife, N.; Crown, D.; Capraro, P.; Trierweiler, R.; Tomazin, S.; Heinemann, A.W. Lessons Learned by Rehabilitation Counselors and Physicians in Services to COVID-19 Long-Haulers: A Qualitative Study. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2021, 66, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, L.; Capotescu, C.; Eyal, G.; Finestone, G. Long COVID and medical gaslighting: Dismissal, delayed diagnosis, and deferred treatment. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Participants (n = 15) |

|---|---|

| Interview Duration (range, minutes) | 20–60 min |

| Participants (n) | 15 |

| 1:1 Interviews (n) | 5 |

| Group Interviews (n) | 2 |

| Group Interviews (range) | 2–8 participants |

| Types of Participant Professional Roles | Registered Nurse, Physiotherapist, Nurse Practitioner, Occupational Therapist, Pharmacist, Recreation Therapist |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Horlick, S.; Krysa, J.A.; Brehon, K.; Pohar Manhas, K.; Kovacs Burns, K.; Russell, K.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Gross, D.P.; Ho, C. Exploring Rehabilitation Provider Experiences of Providing Health Services for People Living with Long COVID in Alberta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247176

Horlick S, Krysa JA, Brehon K, Pohar Manhas K, Kovacs Burns K, Russell K, Papathanassoglou E, Gross DP, Ho C. Exploring Rehabilitation Provider Experiences of Providing Health Services for People Living with Long COVID in Alberta. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(24):7176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247176

Chicago/Turabian StyleHorlick, Sidney, Jacqueline A. Krysa, Katelyn Brehon, Kiran Pohar Manhas, Katharina Kovacs Burns, Kristine Russell, Elizabeth Papathanassoglou, Douglas P. Gross, and Chester Ho. 2023. "Exploring Rehabilitation Provider Experiences of Providing Health Services for People Living with Long COVID in Alberta" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 24: 7176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247176

APA StyleHorlick, S., Krysa, J. A., Brehon, K., Pohar Manhas, K., Kovacs Burns, K., Russell, K., Papathanassoglou, E., Gross, D. P., & Ho, C. (2023). Exploring Rehabilitation Provider Experiences of Providing Health Services for People Living with Long COVID in Alberta. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(24), 7176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247176