Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Innovative Pilot Intervention to Improve the Family Quality of Life of Children with Specific Learning Disabilities—A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Research Goals and Questions

2. Materials and Methods

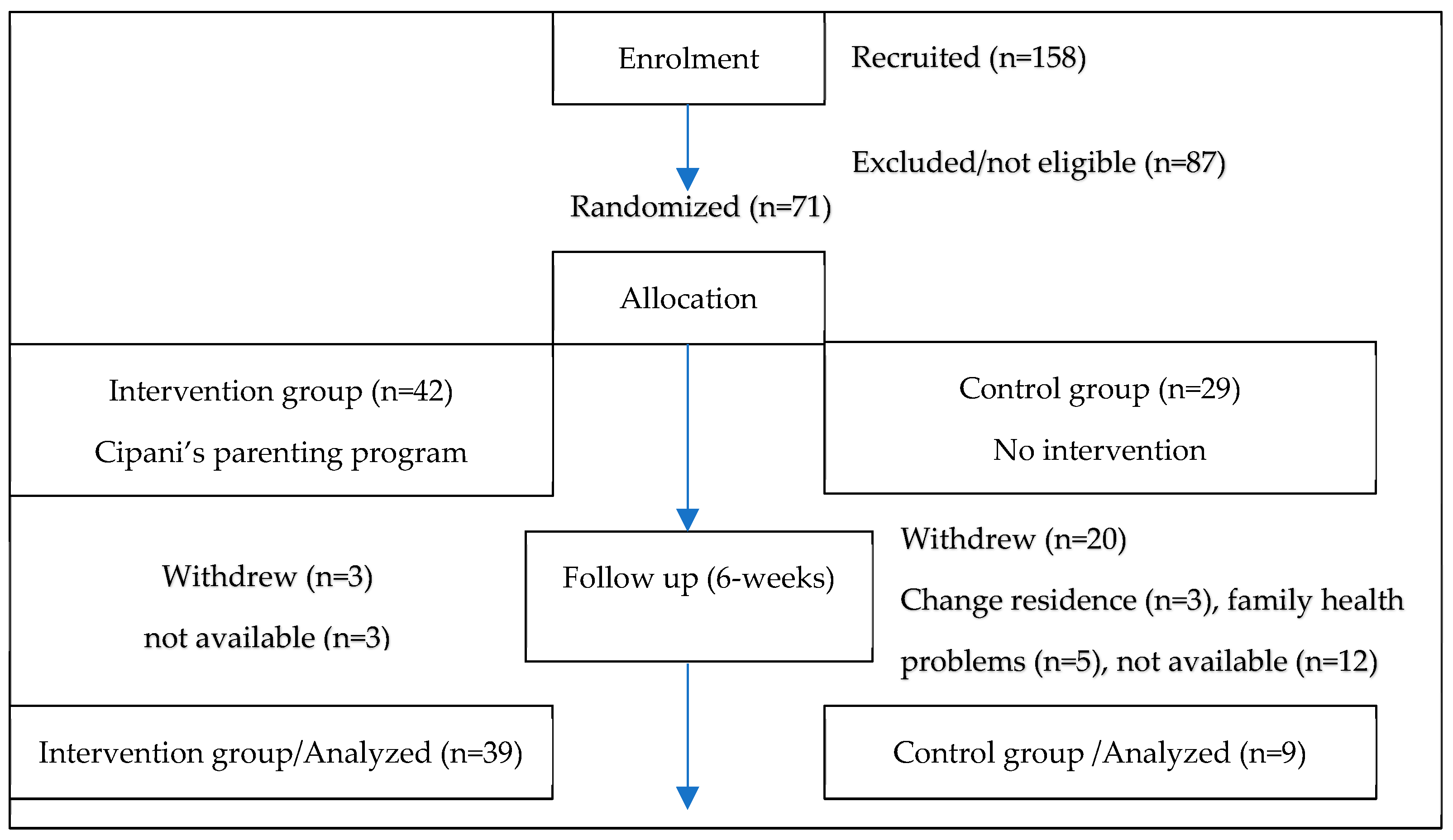

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants’ Recruitment

2.3. Outcome Measures

- The Parenting Style Questionnaire [17]. This questionnaire has good psychometric properties and has been translated and used in several studies such as Matos et al. [18], Önder & Gülay [19] and Tagliabue et al. [20]. It contains 32 items such as “I do praise my child”, “I punish my child by taking away privileges”, “I have outbursts of anger”, “I have difficulty disciplining him”, etc. Participants were invited to indicate how frequently they perform each parenting behavior. Responses ranged between 1 (never) and 5 (always). Out of the 32 items, 13 items form the “Authoritarian parenting style”, 15 items form the “Authoritative parenting style” and 4 items form the “Permissive Parenting style”. A composite score was calculated for each parenting style (ranging from 13 to 65 for “Authoritarian style”, 15 to 75 for “Authoritative style” and 4 to 20 for “permissive style”), with higher scores indicating a higher alignment of the participants to the respective parenting style.

- The Family Quality of Life Scale (FQOL) questionnaire [21]. This questionnaire has been successfully used in previous studies such as Poston et al. [22] and Park et al. [23]. It contains 25 items such as “in your family do you help children learn to be independent”, “in your family do you teach children how to get along with others”, “in your family do you support each other in achieving goals”, etc. Participants were invited to indicate how satisfied they were with each statement reflecting their family life. Responses ranged between 1 (very dissatisfied) and 5 (very satisfied). Out of the 25 items, 6 items form the “Family Interaction”, 6 items form the “Parenting”, 4 items form the “Emotional Well-being”, 5 items form the “Physical/Material Well-being” and 4 items form the “Disability-related support”. A composite score was calculated for each parenting style (ranging from 6 to 30 for “Family Interaction”, 6 to 30 for “Parenting”, 4 to 20 for “Emotional Well-being”, 5 to 25 for “Physical/Material Well-being” and 4 to 20 for “Disability-related Support”), with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction with their family life.

2.4. Content of the Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Comparisons of dimensions of “quality of life” and dimensions of “parenting style” scores were implemented, before and after the intervention, mainly for the intervention group, using paired t-tests;

- Comparisons of “quality of life” and “parenting style” scores were implemented before the intervention between the intervention and the control group. We used an independent samples t-test. However, there were many withdrawals from the second test from control group, and the results after the intervention were unstable for statistical conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Profile

3.2. Reliability of the Study Dimensions

3.3. Effectiveness of the Intervention in Improving Parenting Style and Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blanchet, M.; Assaiante, C. Specific Learning Disorder in Children and Adolescents, a Scoping Review on Motor Impairments and Their Potential Impacts. Children 2022, 9, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofologi, M.; Koulouri, S.; Ntinou, M.; Katsadima, E.; Papantoniou, A.; Staikopoulos, K.; Varsamis, P.; Zaragkas, H.; Moraitou, D.; Papantoniou, G. The Relationship of Effortful Control to Academic Achievement via children’s Learning—Related Behaviors. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 380–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T. Learning Disabilities Statistics and Prevalence, Healthy Place. 2022. Available online: https://www.healthyplace.com/parenting/learning-disabilities/learning-disabilities-statistics-and-prevalence (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- MacLeod, K.; Causton, J.N.; Radel, M.; Radel, P. Rethinking the Individualized Education Plan process: Voices from the otherside of the table. Disabil. Soc. 2017, 32, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, L.; Sionah, L. Draft eu Special Educational Needs (Sen) Policy, Including Specific Learning Disabilities/Difficulties (Sp.L.D.). 2017. Available online: https://euspld.com/policy/ (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Tatavili, T.; Giarmadourou, A. “Learning Disabilities”, literature review. Panhellenic Conf. Educ. Sci. 2020, 8, 1029–1034. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, I.; Everatt, J.; Salter, R. International Book of Dyslexia. A Guide to Practice and Resources; WILEY: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heiman, T. Parents of Children with Disabilities: Resilience, Coping and Future Expectations. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2002, 14, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi, A.; Najmi, B.; Salesi, A.; Chorami, M.; Hoveidafar, R. Parenting stress among mothers of children with different physical, mental, and psychological problems. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Misura, A.K.; Memisevic, H. Quality of life of parents of children with intellectual disabilities in Croatia. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2017, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghtadai, M.; Faramarzi, S.; Abedi, A.; Ghamarani, A. Exploring the lived experiences of mothers of children with Specific Learning Disability (SLD): A phenomenological study. J. Health Based Res. 2021, 9, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Lendrum, A.; Barlow, A.; Humphrey, N. Developing positive school–home relationships through structured conversations with parents of learners with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2015, 15, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forehand, R.; Furey, W.M.; McMahon, R.J. The role of maternal distress in a parent training program to modify child noncompliance. Behav. Psychother. 1984, 12, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R.; Chamberlain, P.; Reid, J.B. A comparative evaluation of parent training procedures. Behav. Ther. 1982, 13, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioka, A.; Salmond, E. Counseling parents of children with Learning Difficulties. Case study in a School Unit of Primary Education. In Proceedings of the Panhellenic Conference of Educational Sciences, Athens, Greece, 1–3 October 2015. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Karande, S.; Kumbhare, N.; Kulkarni, M.; Shah, N. Anxiety levels in mothers of children with specific learning disability. J. Postgrad. Med. 2009, 55, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.; Mandleco, B.; Olsen, S.F.; Hart, C.H. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.; Costa, E.; Pechorro, P.; Nunes, C.; Ayala Nunes, L.; Martins, C. Confirmatory analysis of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) short form in a portuguese sample. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 11, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Önder, A.; Gülay, H. Reliability and validity of parenting styles & dimensions questionnaire. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2009, 1, 508–514. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabue, S.; Olivari, M.G.; Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G.; Confalonieri, E. Measuring adolescents’ perceptions of parenting style during childhood: Psychometric properties of the parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2014, 30, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.; Marquis, J.; Poston, D.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A. Assessing family outcomes: Psychometric evaluation of the beach center family quality of life scale. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poston, D.; Turnbull, A.; Park, J.; Mannan, H.; Marquis, J.; Wang, M. Family quality of life outcomes: A qualitative inquiry launching a long-term research program. Ment. Retard. 2003, 41, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hoffman, L.; Marquis, J.; Turnbull, A.P.; Poston, D.; Mannan, H.; Wang, M.; Nelson, L. Toward assessing family outcomes of service delivery: Validation of a family quality of life survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivoder, I.; Martic-Biocina, S.; Miklecic, J.; Kozina, G. Attitudes and knowledge of parents of preschool children about specific learning disabilities. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 571–574. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika, M.; Das, S.; Choudhury, S. Parents’ attitude towards children and adolescents with intellectual developmental disorder. Int. J. Child Dev. Ment. Health 2017, 5, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cipani, E. A six-week parenting program for child compliance. J. Early Intensive Behav. Interv. 2005, 2, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Razali, N.M.; Wah, Y.B. Power Comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling Tests. J. Stat. Model. Anlytics 2011, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- McKight, P.E.; Najab, J. Kruskal-Wallis Test. Corsini Encycl. Psychol. 2010, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gastwirth, L.J.; Gel, R.Y.; Miao, W. The Impact of Levene’s Test of Equality of Variances on Statistical Theory and Practice. Inst. Math. Stat.-Stat. Sci. 2009, 24, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P. Effectiveness of positive discipline parenting program on parenting style, and child adaptive behavior. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 53, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, M.J.; Carona, C.; Canavarro, M.C.; Moreira, H. Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: The mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, Z.; Ghalenoee, M.; Mohtashami, J.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Esmaieli, R.; Naseri-Salahshour, V. The effectiveness of PMT program on parent-child relationship in parents with ADHD children: A randomized trial. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2018, 32, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Bhargava, R.; Sagar, R.; Mehta, M. Development of Home-Based Intervention Module for Specific Learning Disorder Mixed Type: A Qualitative Study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2022, 44, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginieri-Coccossis, M.; Rotsika, V.; Skevington, S.; Papaevangelou, S.; Malliori, M.; Tomaras, V.; Kokkevi, A. Quality of life in newly diagnosed children with specific learning disabilities (SpLD) and differences from typically developing children: A study of child and parent reports. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Easvaradoss, V. Caregiver Burden in Learning Disability. Indian Psychol. 2015, 1, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wellner, L. Building Parent Trust in the Special Education Setting. Leadership 2012, 41, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kausar, N.; Bibi, B.; Sadia, B.R. Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support in Perceived Stress and Quality of Life among Parents of Children with Special Needs. Glob. Sociol. Rev. 2021, VI, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, N.; Piyal, B. Perceived social support and quality of life of parents of children with Autism. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | Count | Percentage (%) | Count | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 35 | 90 | 27 | 93 |

| Male | 4 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| Age | ||||

| Up to 30 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 31–40 | 17 | 44 | 19 | 66 |

| 41–50 | 17 | 44 | 9 | 31 |

| 51 and above | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single (Married) | 4 | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| Married | 29 | 74 | 21 | 73 |

| Divorced | 4 | 10 | 7 | 24 |

| Single Parent (Married) | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Single Parent (Single) | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary School | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Middle School | 2 | 5 | 4 | 14 |

| High School | 21 | 54 | 13 | 45 |

| Higher Education | 10 | 26 | 9 | 31 |

| Postgraduate Studies | 4 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| Annual Family Income (Euros) | ||||

| Below 10,000 | 12 | 31 | 8 | 28 |

| 10,001–15,000 | 15 | 38 | 6 | 21 |

| 15,001–20,000 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 24 |

| 20,001–25,000 | 7 | 18 | 7 | 24 |

| Over 25,001 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| No Response | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Employed | 25 | 64 | 9 | 31 |

| Unemployed | 9 | 23 | 10 | 34 |

| Self-employed | 4 | 10 | 7 | 24 |

| Homemaker | 1 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

| Number of Children | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| 2 | 22 | 56 | 16 | 55 |

| 3 | 10 | 26 | 7 | 24 |

| 4 | 5 | 13 | 2 | 7 |

| No Response | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| DIMENSION | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Family Interaction | 0.858 | 0.786 |

| Parenting | 0.844 | 0.723 |

| Emotional Well-being | 0.792 | 0.732 |

| Physical/Material Well-being | 0.764 | 0.488 |

| Disability-related Support | 0.806 | 0.663 |

| Authoritative Parenting Style | 0.796 | 0.783 |

| Authoritarian Parenting Style | 0.863 | 0.852 |

| Permissive Parenting Style | 0.544 | 0.641 |

| Dimensions | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Family Interaction | 0.49 |

| Parenting | 0.26 |

| Emotional Well-being | 0.31 |

| Physical Material Well-being | 0.94 |

| Disability-related Support | 0.44 |

| Authoritative Parenting Style | 0.50 |

| Authoritarian Parenting Style | 0.00 |

| Permissive Parenting Style | 0.00 |

| Group Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Group | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | p-Value |

| Family Interaction | intervention | 39 | 4.47 | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| control | 9 | 1.36 | 2.0 | ||

| Parenting | intervention | 39 | 4.42 | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| control | 9 | 1.4 | 2.1 | ||

| Emotional Well-being | intervention | 39 | 3.66 | 0.92 | 0.00 |

| control | 9 | 1.2 | 1.9 | ||

| Physical Material Well-being | intervention | 39 | 4.65 | 0.42 | 0.00 |

| control | 9 | 1.5 | 2.28 | ||

| Disability-related Support | intervention | 39 | 4.51 | 0.52 | 0.00 |

| control | 9 | 1.51 | 2.13 | ||

| Authoritative Parenting Style | intervention | 39 | 4.58 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| control | 9 | 1.51 | 2.13 | ||

| Authoritarian Parenting Style | intervention | 39 | 2.48 | 0.71 | 0.01 |

| control | 9 | 1.49 | 2.11 | ||

| Permissive Parenting Style | intervention | 39 | 1.94 | 0.74 | 0.19 |

| control | 9 | 4.27 | 0.40 | ||

| Sig. (Two-Tailed) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 | Family Interaction | 0.075 |

| Pair 2 | Parenting | 0.039 |

| Pair 3 | Emotional Well-being | 0.140 |

| Pair 4 | Physical Material Well-being | 0.239 |

| Pair 5 | Disability-related Support | 0.096 |

| Pair 6 | Authoritative Parenting Style | 0.155 |

| Pair 7 | Authoritarian Parenting Style | 0.319 |

| Pair 8 | Permissive Parenting Style | 0.202 |

| Initial Clusters | Final Clusters | Results of ANOVA Control with Factor Separation in the New Clusters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Mean Square Error | Df | F | Sig. | |

| Family Interaction | 1.67 | 5.00 | 4.03 | 4.60 | 0.261 | 74 | 20.71 | 0.000 |

| Parenting | 1.50 | 5.00 | 3.91 | 4.55 | 0.341 | 74 | 20.112 | 0.000 |

| Emotional Well-being | 1.75 | 5.00 | 2.64 | 4.08 | 0.469 | 74 | 74.491 | 0.000 |

| Physical/Material Well-being | 2.80 | 5.00 | 4.30 | 4.80 | 0.197 | 74 | 19.029 | 0.000 |

| Disability-related Support | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.86 | 4.73 | 0.333 | 74 | 38.208 | 0.000 |

| Authoritative Parenting Style | 4.77 | 5.00 | 4.44 | 4.63 | 0.115 | 74 | 5.574 | 0.021 |

| Authoritarian Parenting Style | 2.08 | 1.17 | 2.80 | 2.52 | 0.584 | 74 | 2.34 | 0.130 |

| Permissive Parenting Style | 2.50 | 1.00 | 2.74 | 1.76 | 0.401 | 74 | 40.187 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedioti, N.; Lioliou, S.; Koutra, K.; Parlalis, S.; Papadakaki, M. Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Innovative Pilot Intervention to Improve the Family Quality of Life of Children with Specific Learning Disabilities—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247192

Pedioti N, Lioliou S, Koutra K, Parlalis S, Papadakaki M. Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Innovative Pilot Intervention to Improve the Family Quality of Life of Children with Specific Learning Disabilities—A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(24):7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247192

Chicago/Turabian StylePedioti, Nektaria, Stavroula Lioliou, Katerina Koutra, Stavros Parlalis, and Maria Papadakaki. 2023. "Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Innovative Pilot Intervention to Improve the Family Quality of Life of Children with Specific Learning Disabilities—A Randomized Controlled Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 24: 7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247192

APA StylePedioti, N., Lioliou, S., Koutra, K., Parlalis, S., & Papadakaki, M. (2023). Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Innovative Pilot Intervention to Improve the Family Quality of Life of Children with Specific Learning Disabilities—A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(24), 7192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20247192