Experiences of Young People and Their Carers with a Rural Mobile Mental Health Support Service: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Service Models and Innovations

1.2. Voices of Young People Regarding Mental Health Services

2. Method

2.1. Setting and Design

2.2. Recruitment and Sample Characteristics

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

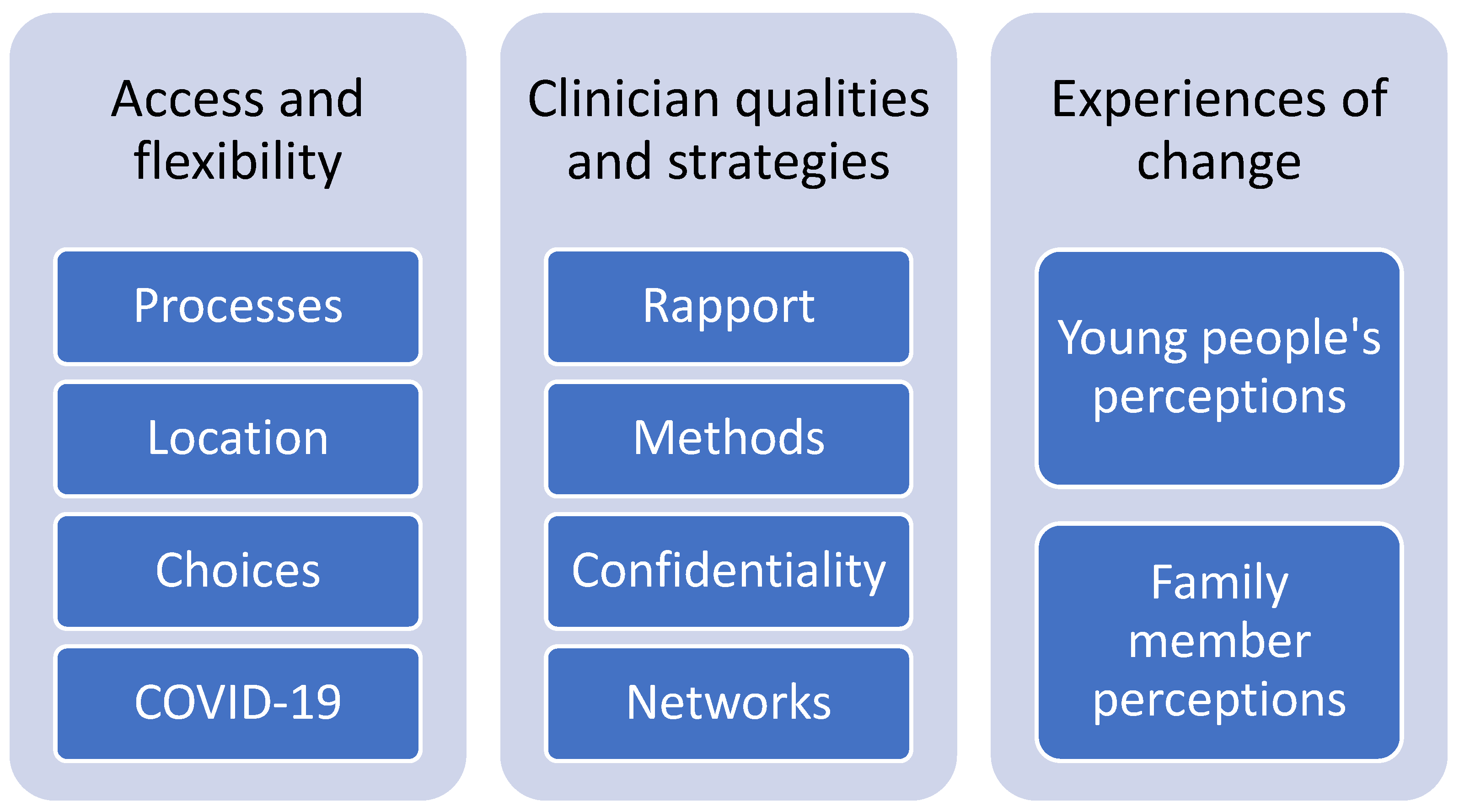

3. Results

3.1. Access and Flexibility

3.2. Processes

It was a super easy process. I was meeting with [Youth Worker at school], and then just one day, she was like, “Oh, this is [clinician]. You can pick whether you want to see her, and she can help with strategies and stuff like that.” So for me, it was like a super easy process.(YP11)

[YP] did forget the [appointment] one day and she sent [clinician] an email immediately once she realised, and [clinician] was like, “Oh, it’s okay. I’ve got a spot open this afternoon, would you like to meet?”, so it didn’t make her feel as bad, because [YP] is a worrier, she worries a lot.(FM07)

She knows that she’s got someone to reach out to and talk to. … It’s built a lot of trust, I think for [YP] and she’s not feeling so isolated and alone waiting for her counselling appointment.…There’s no certain [number of] visits. There’s no “Okay I can only fit you in three times” or “You’ve got to wait two months before your next appointment”.(FM04)

I like the fact it was free. Because the fact that we don’t have to pay for it makes me feel really good…. makes it feel a lot more accessible…, which I find really good. If it wasn’t [free] I would have to ask my parents, and I don’t want my parents to know about it.(YP06)

3.3. Location

Just getting to like, find out about them. I found out through school, and I don’t know how else I’d find out about it.(YP02)

We’re located 40 kms from our local town… My husband works full-time and I work part-time so being able to access those services has been tricky. And that’s what’s great about [service]-the fact that [clinician] goes to the school, so we don’t have to be concerned about how [YP] is going to get to their appointment and whether we have to take time off work or whatever.(FM8)

3.4. Choices

I couldn’t believe that she met out of office hours. They did meet up at a cafe to talk. She provided support to get her to work, which was wonderful being out of town. It wasn’t a big journey, but just having that flexibility again, building that trust, building that [sense of] ‘I’ve got someone who is going to be there at all different times’.(FM01)

3.5. COVID-19

The actual conversations we have [on Zoom] are the normal conversations we usually have. And she can show me, like if she’s ever doing the drawings or like writing up stuff, she shows me what she writes. It doesn’t change anything that way at all.(YP06)

I think in-person makes a bigger difference, and I like having it in person. You can read your body language more, you can read hers [clinician’s] more.(YP11)

I find it more easy to talk over Zoom but that’s just me. I don’t really like talking in person.(YP08)

Sometimes it’s annoying to do it over like over video call because my internet is absolutely horrid.(YP01)

I feel people are hearing my conversations [when I’m on a Zoom call at home]. I don’t want my family hearing them much.(YP10)

I think that even though [YP] would like to meet [clinician] face-to-face sometimes, I feel like it’s still been good for her to meet over Zoom. It’s still been really helpful.(FM07)

No, not at all because [clinician] has actually checked in once or twice a week with [YP]. I don’t feel that it has been impacted. And again, [YP] knows that [clinician] is just a text message away.(FM01)

[YP] has had the option to do an over-the-phone with [clinician] since all this COVID stuffs happened, but she didn’t want to do the over-the-phone thing… she seems quite happy with waiting to go back to school… They were working on a drawing thing and [clinician] dropped that off at my work for me so I could take it home to [YP], and then she could just do stuff with it if she wanted to.(FM04)

3.6. Clinician Qualities and Strategies

3.7. Rapport

They [clinician] are very friendly, you feel like you can approach them. They don’t rush you and they’re very patient, which is really good. Like, they give you time and they’re really understanding.(YP02)

3.8. Methods

I learned a lot of strategies, to help control my stress and my anxiety that I can use in everyday life, and it makes me less anxious. I get the worst anxiety when I’m in a group setting, and she’s helped me to know… the things that I can do to help me calm myself down, and not get as anxious around people.(YP11)

Like there’s been cards to show how to do breathing and there’s been worksheets and sometimes she gave me a booklet to colour in. Like all different activities to do.(YP05)

So when I’m straight talking, I don’t really like it and I feel less comfortable, but if I’m drawing it gets my mind off that and I just let everything out.(YP08)

I liked that she’s been a bit creative about things like, you know, [YP] is a drawer, so she sometimes gets [YP] to draw how she’s feeling and things like that. She’s sort of just taken the time to get to know her and find out what will work to get her to talk; not just a blanket sort of thing, it’s actually specific to her needs.(FM03)

3.9. Confidentiality

I really like the fact that it is just us [young person and clinician]. We decide when we want to talk. And… we make all the calls on that stuff [who else to involve].(YP06)

And if there’s anything that comes up that needs addressing, I like how that gets fed back to us, but I also like that the girls are given their own privacy to have their sessions and that I’m not part of them at all.(FM06)

I knew that [clinician] had the girls’ best interests at heart and if I needed to know anything she would let me know.(FM08)

3.10. Networks

My anxiety was making me physically ill… She [clinician] asked if she could refer me to a dietician… She came with me… and it was really good. I learned a lot from that.(YP06)

I’ve liked the fact that she [clinician] helped me get a psychologist to help me with my behavioural and attention problems and I might have a full diagnosis.(YP07)

[Clinician] was very instrumental in suggesting the doctors and the psychologist we ended up seeing in [town]… She attended those visits with [YP] when I was unable to get there… All that support, just being able to attend the appointment, and for me to be able to see [YP] through [clinician] eyes, what she saw, all with his permission to share information. I know that everything wasn’t shared because it didn’t need to be, but it was really good to have someone there helping him open up.(FM05)

4. Experiences of Change

4.1. Young People’s Perceptions of Change

Like with my strategies and stuff, it’s helped me with my depression and anxiety, and it’s made my life better … So before I went to [clinician], I had a lot of mental problems and I couldn’t really do anything and I didn’t know how to help myself. And then when I came to [the service], [clinician] helped me with a lot of my depression stuff and the strategies. And whenever I have those moods, I remember what she talked about and it helps.(YP08)

Just I’m a whole different kid pretty much. … I feel more open to talking about other things, because I’m so used to talking about them now…. I’m not moping around [at home] all the time … I’m doing some stuff instead of just lying in bed(YP05)

I’m a lot happier, just like in general. A lot more confident in myself. It’s made it like for me I’m I can talk to people a lot easier now. I’ve found like I’ve been a lot more positive about life and it’s made my life a lot easier…. It’s just put a big impact on my life. Like, it’s just amazing.(YP02)

I wasn’t really involved [in school]–I had only a couple friends at school ‘cause I don’t really like… wanting to socialise with people, just ‘cause of my anxiety, and past things that have happened with people. So [clinician] has helped me branch out. I’ve got more friends at school now, and I do more things with school, and just get more involved which I didn’t do before.(YP11)

I talk to my family about a lot more things. [Clinician] helped me through ways to talk to my family. That was really good.(YP03)

4.2. Family Members Perceptions of Change

She [YP] has changed probably in the last eight months… She has been more open. She has engaged in the family a lot more. She’s not fighting with her younger siblings… she’s starting to get a better understanding of how to control her emotions. It’s opened up channels of communication with me and [YP] that I didn’t know how to do… [clinician] has done a wonderful job with teaching [YP] all these tools–it’s really helping.(FM02)

Definitely a big change in communication, huge change in her moods even, she’s just a lot happier, she’s a lot more relaxed, and she does seem to have the strategies now when she’s not feeling so good… She’s a different kid at the moment. We’ve been talking over the last few weeks about how nice it is to be around her again, having her being the normal her again, the happy her.(FM03)

We are miles ahead of where we were. [YP] is now employed. He has his license-he turned 18 last year and was unable to have the confidence to do the tests and the driving. He’s a year behind but he’s now achieved his license, he’s an independent driver and he has a part-time casual job. That job was actually mentioned to him by [clinician]. He has progressed in the last few months probably to a point that we never thought we’d ever get to. I know for a fact we wouldn’t be there without [the service] being involved…. giving [YP] his confidence back, bringing that child back to who he was after a very bad incident.(FM05)

5. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- World Health Organization. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to Support Country Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.; Johnson, S.; Hafekost, J.; Boterhoven De Haan, K.; Sawyer, M.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, S.R. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.J.; Humphreys, J.S.; Ward, B.; Chisholm, M.; Buykx, P.; McGrail, M.; Wakerman, J. Helping policy-makers address rural health access problems. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2013, 21, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Policy Writing Group. Fit for Purpose: Improving Mental Health Services for Young People Living in Rural and Remote Australia; Orygen: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Community Affairs References Committee. Accessibility and Quality of Mental Health Services in Rural and Remote Australia; Senate: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.; Buchan, J.; Cometto, G.; David, B.; Dussault, G.; Fogstad, H.; Fronteira, I.; Lozano, R.; Nyonator, F.; Pablos-Mendez, A.; et al. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: Fostering equity and effective coverage. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechel, B.; Dzakula, A.; Duran, A.; Fattore, G.; Edwards, N.; Grignon, M.; Haas, M.; Habicht, T.; Marchildon, G.P.; Moreno, A.; et al. Hospitals in rural or remote areas: An exploratory review of policies in 8 high-income countries. Health Policy 2016, 120, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsden, R.; Colbran, R.; Linehan, T.; Edwards, M.; Varinli, H.; Ripper, C.; Kerr, A.; Harvey, A.; Naden, P.; McLachlan, S.; et al. Partnering to address rural health workforce challenges in Western NSW. J. Integr. Care 2020, 28, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.; Dew, A.; Lincoln, M.; Bundy, A.; Chedid, R.J.; Bulkeley, K.; Brentnall, J.; Veitch, C. Should I stay or should I go? Exploring the job preferences of allied health professionals working with people with disability in rural Australia. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Contracting Out of Government Services, Second Report: Chapter 2 The Tendering Process; Parliament of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, O.S.; Johnson, A.M.; Dowling, N.L.; Robinson, T.; Ng, C.H.; Yucel, M.; Segrave, R.A. Are Australian Mental Health Services Ready for Therapeutic Virtual Reality? An Investigation of Knowledge, Attitudes, Implementation Barriers and Enablers. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 792663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawke, L.D.; Sheikhan, N.Y.; MacCon, K.; Henderson, J. Going virtual: Youth attitudes toward and experiences of virtual mental health and substance use services during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.; Webster, E.; Chambers, B.; Nott, S. “This is streets ahead of what we used to do”: Staff perceptions of virtual clinical pharmacy services in rural and remote Australian hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Waller, M.; Pandya, A.; Portnoy, J. A Review of Patient and Provider Satisfaction with Telemedicine. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; Treacy, M.P.; Sheridan, A. ‘It just doesn’t feel right’: A mixed methods study of help-seeking in Irish schools. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2017, 10, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Kataoka, S.H.; Bear, L.; Lau, A.S. Differences in School-Based Referrals for Mental Health Care: Understanding Racial/Ethnic Disparities Between Asian American and Latino Youth. Sch. Ment. Health 2014, 6, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, A.; Weist, M.D.; McCall, M.; Kloos, B.; Miller, E.; George, M.W. Qualitative analysis of key informant interviews about adolescent stigma surrounding use of school mental health services. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2016, 18, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABC News. Doctors to be Stationed in 50 Queensland Schools, Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk Says. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-13/doctors-gps-schools-queensland-50-2022/100534246 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- CatholicCare Sydney. Support in Schools. Available online: https://www.catholiccare.org/family-youth-children/schools/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Lawrence, P.J.; Evdoka-Burton, G.; Waite, P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirker, R.S.; Brown, J.; Clarke, S. Children and Young People’s Experiences of Mental Health Services in Healthcare Settings: An Integrated Review. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2022, 45, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Velasco, A.; Cruz, I.S.S.; Billings, J.; Jimenez, M.; Rowe, S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, A.; Isbister, C. Young Men’s Experiences of Accessing and Receiving Help From Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services Following Self-Harm. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 2158244017745112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haavik, L.; Joa, I.; Hatloy, K.; Stain, H.J.; Langeveld, J. Help seeking for mental health problems in an adolescent population: The effect of gender. J. Ment. Health 2019, 28, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design; Bis: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Western NSW Primary Health Network. Western New South Wales Primary Health Network Health Profile 2021; Western NSW Primary Health Network: Dubbo, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PHIDU. Social Health Atlases of Australia; Torrens University of Australia Public Health Information Development Unit: Adelaide, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Western NSW PHN. Western NSW Primary Health Network Needs Assessment, 2019–2022; Western NSW Primary Health Network: Dubbo, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas, B.V.; Smith, N.; Mitton, C. The Qualitative Descriptive Approach in International Comparative Studies: Using Online Qualitative Surveys. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2018, 7, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. Understanding and Validity in Qualitative Research. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1992, 62, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rijnsoever, F.J. (I Can’t Get No) Saturation: A simulation and guidelines for sample sizes in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, C.; Casey, D.; Shaw, D.; Murphy, K. Rigour in qualitative case-study research. Nurs. Res. 2013, 20, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allan, J.; Thompson, A. Experiences of Young People and Their Carers with a Rural Mobile Mental Health Support Service: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031774

Allan J, Thompson A. Experiences of Young People and Their Carers with a Rural Mobile Mental Health Support Service: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031774

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllan, Julaine, and Anna Thompson. 2023. "Experiences of Young People and Their Carers with a Rural Mobile Mental Health Support Service: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031774

APA StyleAllan, J., & Thompson, A. (2023). Experiences of Young People and Their Carers with a Rural Mobile Mental Health Support Service: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031774