The Mediation of Care and Overprotection between Parent-Adolescent Conflicts and Adolescents’ Psychological Difficulties during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Which Role for Fathers?

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- To investigate youths’ emotional and behavioral symptoms during the pandemic, focusing on the predicting effect of parent-adolescent conflict. With regard to this, it was hypothesized that higher levels of perceived conflicts with parents could predict higher levels of symptoms reported by youths one year later;

- -

- To investigate the association between parenting dimensions (care and overprotection) and youths’ adjustment. It was hypothesized that high parental overprotection and low care would be associated with higher symptoms in youths;

- -

- To explore the mediating effects of parenting dimensions (mother and father care and overprotection) in the relationship between parent-adolescent conflict and youth symptoms after one year. As no previous studies explored this mediation, we did not make any specific hypothesis;

- -

- To explore whether this mediation was moderated by adolescent gender. Even in this case, specific hypotheses could not be pronounced.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Parent-Adolescent Conflict

2.3.2. Parenting

2.3.3. Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

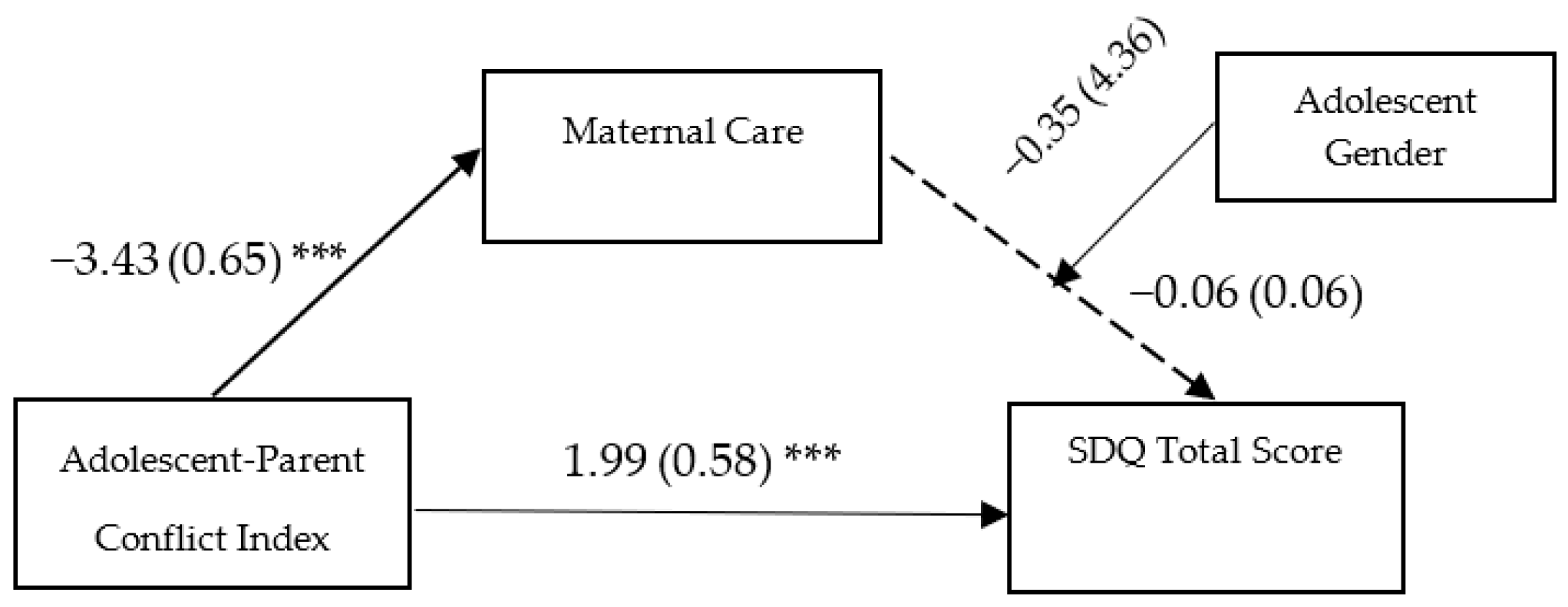

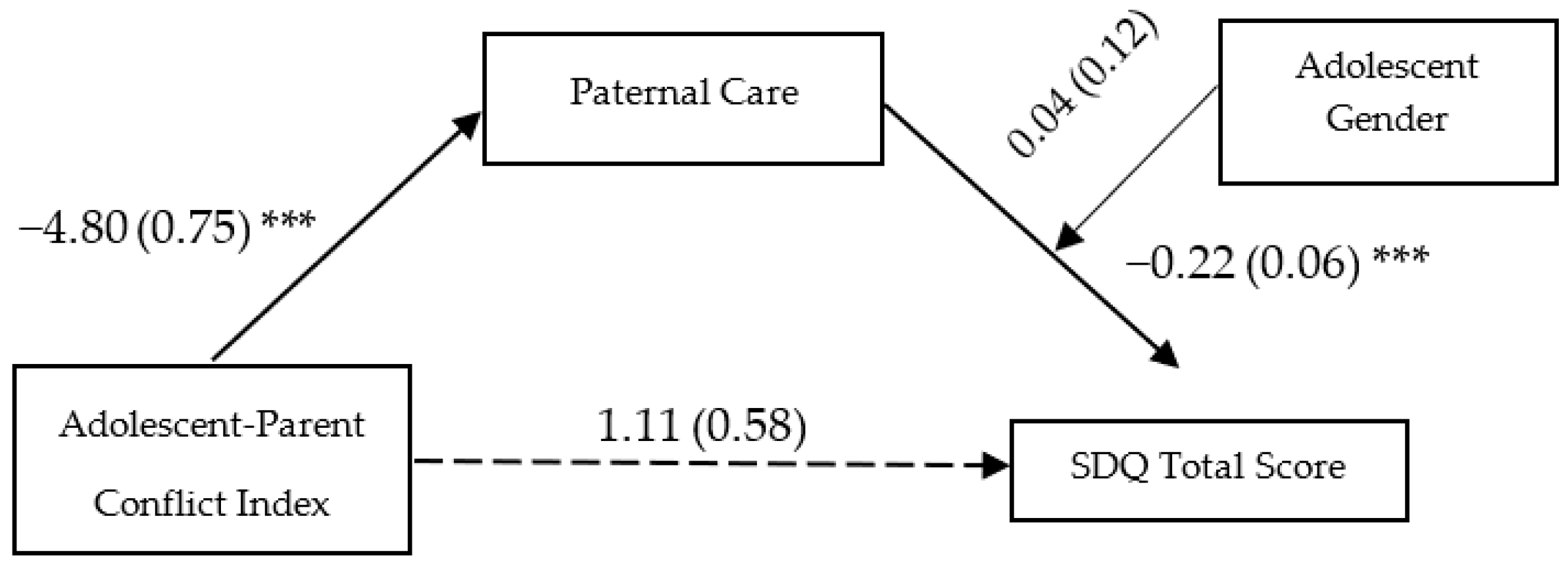

3.3. Main Analyses: Moderated Mediation Models

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limits

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, G.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodun, O.; Rohde, L.A.; Srinath, S.; Ulkuer, N.; Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney, D.G.; Peterson, M.D. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigerio, A.; Rucci, P.; Goodman, R.; Ammaniti, M.; Carlet, O.; Cavolina, P.; De Girolamo, G.; Lenti, C.; Lucarelli, L.; Mani, E.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders among adolescents in Italy: The PrISMA study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 18, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, J.R.; Baumler, E.; Wood, L.; Guillot-Wright, S.; Torres, E.; Thiel, M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescent Mental Health and Substance Use. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccanello, D.; Rocca, E.; Vicentini, G.; Brondino, M. Eighteen Months of COVID-19 Pandemic Through the Lenses of Self or Others: A Meta-Analysis on Children and Adolescents' Mental Health. Child Youth Care Forum 2022, 29, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffo, E.; Asta, L.; Scandroglio, F. Predictors of mental health worsening among children and adolescents during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, L.; Meloni, S.; Lanfredi, M.; Ferrari, C.; Geviti, A.; Cattaneo, A.; Rossi, R. Adolescents’ mental health and maladaptive behaviors before the COVID-19 pandemic and 1-year after: Analysis of trajectories over time and associated factors. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Mazzeschi, C.; Delvecchio, E. The Impact of Parental Stress on Italian Adolescents’ Internalizing Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-being Among Children and Adolescents During the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzelli, M.G.; Furente, F.; Colacicco, G.; Annecchini, F.; Margari, A.; Gabellone, A.; Margari, L.; Matera, E. Implication of COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescent Mental Health: An Analysis of the Psychiatric Counseling from the Emergency Room of an Italian University Hospital in the Years 2019–2021. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freisthler, B.; Gruenewald, P.J.; Tebben, E.; McCarthy, K.S.; Wolf, J.P. Understanding at-the-moment stress for parents during COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 279, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, J.J.; Achterhof, R.; Lafit, G.; Bamps, E.; Hagemann, N.; Hiekkaranta, A.P.; Hermans, K.S.F.M.; Lecei, A.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Kirtley, O.J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Adolescents’ Daily Lives: The Role of Parent-Child Relationship Quality. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 623–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.T.; Henry, D.A.; Del Toro, J.; Scanlon, C.L.; Schall, J.D. COVID-19 Employment Status, Dyadic Family Relationships, and Child Psychological Well-Being. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, M.; Forresi, B.; Giani, L.; Michelini, G.; Scaini, S. Italian Children’s Well-Being after Lockdown: Predictors of Psychopathological Symptoms in Times of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, S.; Badinlou, F.; Brocki, K.C.; Frick, M.A.; Ronchi, L.; Hughes, C. Family Function and Child Adjustment Difficulties in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaini, S.; Caputi, M.; Giani, L.; Forresi, B. Temperament profiles to differentiate-between stress-resilient and stress affected children during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Hub 2021, 38, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Jia, F.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Hao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Risk factors and prediction nomogram model for psychosocial and behavioural problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national multicentre study: Risk Factors of Childhood Psychosocial Problems. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Henry, D.A.; Scanlon, C.L.; Del Toro, J.; Voltin, S.E. Adolescent Psychosocial Adjustment during COVID-19: An Intensive Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.C.H. Dyadic associations between COVID-19-related stress and mental well-being among parents and children in Hong Kong: An actor-partner interdependence model approach. Fam. Process 2022, 61, 1730–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.L.; Russell, B.S.; Tambling, R.R.; Britner, P.A.; Hutchison, M.; Tomkunas, A.J. Predictors of children’s emotion regulation outcomes during COVID-19: Role of conflict within the family. Fam. Relat. 2022, 17, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, N.; Tian, L. The Parent-Adolescent Relationship and Risk-Taking Behaviors Among Chinese Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Self-Control. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, A.T.; Godwin, J.; Alampay, L.P.; Lansford, J.E.; Bacchini, D.; Bornstein, M.H.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Di Giunta, L.; Dodge, K.A.; Gurdal, S.; et al. Parent-adolescent relationship quality as a moderator of links between COVID-19 disruption and reported changes in mothers’ and young adults’ adjustment in five countries. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1648–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Ander, B.; Gurdal, S.; Sorbring, E. Adolescent smoking, alcohol use, inebriation, and use of narcotics during the Covid-19 pandemic. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weymouth, B.B.; Buehler, C. Adolescent and Parental Contributions to Parent–Adolescent Hostility Across Early Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Rose, R.A.; Evans, C.B.; Cotter, K.L.; Bower, M.; Bacallao, M. Familial influences on internalizing symptomatology in Latino adolescents: An ecological analysis of parent mental health and acculturation dynamics. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 1191–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Bacallao, M.L.; Cotter, K.L.; Evans, C.B. The effects of positive and negative parenting practices on adolescent mental health outcomes in a multicultural sample of rural youth. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 46, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, M.D.; Branje, S.J.T.; Meeus, W.H.J. Conflict resolution in parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent delinquency. J. Early Adolesc. 2008, 28, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Thompson, E.A.; Walsh, E.M.; Schepp, K.G. Trajectories of parent-adolescent relationship quality among at-risk youth: Parental depression and adolescent developmental outcomes. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 29, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, V.; Pastorelli, C.; Eisenberg, N.; Caffo, E.; Forresi, B.; Gerbino, M. The development of perceived maternal hostile, aggressive conflict from adolescence to early adulthood: Antecedents and outcomes. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, B.; Coy, K.C.; Collins, W.A. Reconsidering changes in parent-child conflict across adolescence: A meta-analysis. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sheikh, M.; Elmore-Staton, L. The link between marital conflict and child adjustment: Parent–child conflict and per-ceived attachments as mediators, potentiators, and mitigators of risk. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasch, L.A.; Deardorff, J.; Tschann, J.M.; Flores, E.; Penilla, C.; Pantoja, P. Acculturation, parent–adolescent conflict, and adolescent adjustment in Mexican-American families. Fam. Process 2006, 45, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galambos, N.L.; Barker, E.T.; Almeida, D.M. Parents do matter: Trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, R.A.; Barber, B.K.; Crane, D.R. Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth: The relationships to academic grades, delinquency, and depression. J. Fam. Issues 2006, 27, 1335–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Qadir, F.; Chan, S.W.; Schwannauer, M. Parental bonding and adolescents depressive and anxious symptoms in Pakistan. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 228, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Bullock, A.; Yang, P.; Liu, J. Psychological control and internalizing problems: The mediating role of mother-child relationship quality. Parenting 2021, 21, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.; Steele, E.H.; Story, A. Effects of parental internalizing problems on irritability in adolescents: Moderation by parental warmth and overprotection. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2791–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMoyne, T.; Buchanan, T. Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociol. Spectr. 2011, 31, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y. Too much of a good thing: Perceived overparenting and wellbeing of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 1791–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, J.D.; Paksarian, D.; He, J.P.; Merikangas, K.R. Parenting style and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffagnato, A.; Angelico, C.; Fasolato, R.; Sale, E.; Gatta, M.; Miscioscia, M. Parental Bonding and Children's Psychopathology: A Transgenerational View Point. Children 2021, 8, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.T. Overparenting, Parent-Child Conflict and Anxiety among Chinese Adolescents: A Cross-Lagged Panel Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Ju, J.; Kang, L.; Bian, Y. “More control, more conflicts?” Clarifying the longitudinal relations between parental psychological Control and parent-adolescent Conflict by disentangling between-family effects from within-family effects. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, L.M.; Cummings, E.; Goeke-Morey, M.C. Parental psychological distress, parent–child relationship qualities, and child adjustment: Direct, mediating, and reciprocal pathways. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2005, 5, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.M.; LoBraico, E.J. Elaborating on premature adolescent autonomy: Linking variation in daily family processes to developmental risk. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Hofer, C.; Spinrad, T.L.; Gershoff, E.T.; Valiente, C.; Losoya, S.H.; Zhou, Q.; Cumberland, A.; Liew, J.; Reiser, M.; et al. Understanding mother-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2008, 73, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.; Ford, C.A.; Miller, V.A. Daily Parent-Teen Conflict and Parent and Adolescent Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Daily and Person-Level Warmth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1601–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülow, A.; Keijsers, L.; Boele, S.; van Roekel, E.; Denissen, J.J.A. Parenting adolescents in times of a pandemic: Changes in relationship quality, autonomy support, and parental control? Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Palmer, A.R. Parenting to Promote Resilience in Children. In Handbook of Parenting; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S.; Motti-Stefanidi, F. Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2020, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruining, H.; Bartels, M.; Polderman, T.J.; Popma, A. COVID-19 and child and adolescent psychiatry: An unexpected blessing for part of our population? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 30, 1139–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.; Dai, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Fang, X. Patterns and predictors of adolescent life change during the COVID-19 pandemic: A person-centered approach. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Tupling, H.; Brown, L.B. A parental bonding instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1979, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Attachment (Vol. 1); Basic Book: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Main, M. Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: 2. Overview of the field of attachment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W.; Clara, I.P. The Parental Bonding Instrument: Confirmatory evidence for a three-factor model in a psychiatric clinical sample and in 109 the National Comorbidity Survey. Soc. Psychol. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2000, 35, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapci, E.; Kucuker, S. The Parental Bonding Instrument: Evaluation of its psychometric properties with Turkish University students. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2006, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.; Wickramaratne, P.; Weissman, M. The stability of parental bonding reports: A 20-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 125, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scinto, A.; Marinangeli, M.G.; Kalyvoka, A.; Daneluzzo, E.; Rossi, A. Utilizzazione della versione italiana del Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in un campione clinico ed in un campione di studenti: Uno studio di analisi fattoriale esplorativa e confermatoria [The use of the Italian version of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in a clinical sample and in a student group: An exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis study]. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 1999, 8, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, L.; Tarsitani, A.; Toni, A.; Maraone, A.; Roselli, V.; Fabi, E.; De Michele, F.; Gaviano, I.; Biondi, M. Validity and reliability of the Italian version of the Measure of Parental Style. J. Psychopathol. 2005, 19, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essau, C.A.; Olaya, B.; Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X.; Pauli, G.; Gilvarry, C.; Bray, D.; O’callaghan, J.; Ollendick, T.H. Psychometric properties of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire from five European countries. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yogman, M.W.; Eppel, A.M. The Role of Fathers in Child and Family Health. In Engaged Fatherhood for Men, Families and Gender Equality; Grau Grau, M., las Heras Maestro, M., Riley Bowles, H., Eds.; Contributions to Management Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A.; Rohner, R.P. Pancultural associations between perceived parental acceptance and psychological adjustment of children and adults: A meta-analytic review of worldwide research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2012, 43, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziano, A. The importance of paternal warmth. Cross-Cult. Res. 2003, 37, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forehand, R.; Nousiainen, S. Maternal and paternal parenting: Critical dimensions in adolescent functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 1993, 7, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phares, V.; Fields, S.; Kamboukos, D. Fathers’ and mothers’ involvement with their adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L. Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gend. Soc. 2006, 20, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.; Richards, M.H. Divergent Realities: The Emotional Lives of Mothers, Fathers, and Adolescents; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L.; Silk, J.S. Parenting adolescents. In Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 1: Children and Parenting, 2nd ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hosley, C.A.; Montemayor, R. Fathers and adolescents. In The Role of the Father in Child Development, 3rd ed.; Lamb, M.E., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 162–178. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn, M.D.; Branje, S.T.; Meeus, W.J. Developmental changes in conflict resolution styles in parent–adolescent relationships: A four-wave longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Dev. 1985, 56, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.; Barber, B.K.; Olsen, J.A.; Maughan, S.L.; Erickson, L.D.; Ward, D.; Stolz, H.E. A multi-national study of interparental conflict, parenting, and adolescent functioning: South Africa, Bangladesh, China, India, Bosnia, Germany, Palestine, Colombia, and the United States. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2004, 35, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.N. Maternal depression in association with fathers’ involvement with their infants: Spillover or compensation/buffering? Infant Ment. Health J. 2014, 35, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, G.W.; Fabricius, W.V.; Stevenson, M.M.; Parke, R.D.; Cookston, J.T.; Braver, S.L.; Saenz, D.S. Effects of the interparental relationship on adolescents’ emotional security and adjustment: The important role of fathers. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1666–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T. A longitudinal study of the relations between parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent psychological well-being. J. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 159, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambelli, R.; Cimino, S.; Marzilli, E.; Ballarotto, G.; Cerniglia, L. Late Adolescents’ Attachment to Parents and Peers and Psychological Distress Resulting from COVID-19. A Study on the Mediation Role of Alexithymia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, S.; Seiffge-Krenke, I. Fathers and Adolescents: Developmental and Clinical Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Spera, C. Adolescents’ perceptions of parental goals, practices, and styles in relation to their motivation and achievement. J. Early Adolesc. 2006, 26, 456–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognli, E.W.; Aalberg, M.; Czajkowski, N.O. Using informant discrepancies in report of parent-adolescent conflict to predict hopelessness in adolescent depression. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGue, M.; Elkins, I.; Walden, B.; Iacono, W.G. Perceptions of the parent–adolescent relationship: A longitudinal investigation. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymouth, B.B.; Buehler, C.; Zhou, N.; Henson, R.A. A meta-analysis of parent–adolescent conflict: Disagreement, hostility, and youth maladjustment. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.A.; Jain, A.; Wilson, T.; Deros, D.E.; Jacobs, I.; Dunn, E.J.; Aldao, A.; Stadnik, R.; De Los Reyes, A. Moderated mediation of the link between parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent risk-taking: The role of physiological regulation and hostile behavior in an experimentally controlled investigation. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess 2019, 41, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sturge-Apple, M.L.; Martin, M.J.; Davies, P.T. Interactive effects of family instability and adolescent stress reactivity on socioemotional functioning. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decarli, A.; Schulz, A.; Pierrehumbert, B.; Vögele, C. Mothers’ and fathers’ reflective functioning and its association with parenting behaviors and cortisol reactivity during a conflict interaction with their adolescent children. Emotion 2022. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosco, G.M.; Mak, H.W.; Ramos, A.; LoBraico, E.; Lippold, M. Exploring the promise of assessing dynamic characteristics of the family for predicting adolescent risk outcomes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forresi, B.; Caputi, M.; Scaini, S.; Caffo, E.; Aggazzotti, G.; Righi, E. Parental Internalizing Psychopathology and PTSD in Offspring after the 2012 Earthquake in Italy. Children 2021, 8, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.S. Parents’ involvement and adolescents’ school adjustment: Teacher–student relationships as a mechanism of change. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.S.; Arsiwalla, D.D. Commentary on special section on ‘‘bidirectional parent–child relationships’’: The continuing evolution of dynamic, transactional models of parenting and youth behavior problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.C.; Chen, W.C.; Liu, T.H. Emotional Reactivity to Daily Family Conflicts: Testing the Within-Person Sensitization. J. Res. Adolesc. 2022. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, J.M.; Krishnakumar, A.; Buehler, C. Marital conflict, parent–child relations, and youth maladjustment: A longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. J. Fam. Issues 2006, 27, 951–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M.; Stocker, C. Family functioning and children’s adjustment: Associations among parents’ depressed mood, marital hostility, parent–child hostility, and children’s adjustment. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Merrilees, C.E.; George, M.W. Fathers, marriages and families: Revisiting and updating the framework for fathering in family context. In The Role of the Father in Child Development, 5th ed.; Lamb, M., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 154–176. [Google Scholar]

- Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Göbel, A.; Bindt, C.; Mudra, S. Parental Reflective Functioning and Its Association with Parenting Behaviors in Infancy and Early Childhood: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 765312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbassat, N.; Priel, B. Parenting and adolescent adjustment: The role of parental reflective function. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean (SD) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Care (M) | 24.65 (7.61) | 0.512 *** | −0.410 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.189 ** | −0.364 *** | −0.108 |

| 2. Care (P) | 20.08 (9.09) | - | −0.295 *** | −0.424 *** | −0.370 *** | −0.436 *** | −0.082 |

| 3. Over protection (M) | 12.62 (6.88) | - | 0.673 *** | 0.095 | 0.332 *** | 0.014 | |

| 4. Over protection (P) | 11.32 (6.71) | - | 0.225 ** | 0.397 *** | −0.048 | ||

| 5. SDQ Total | 16.77 (6.24) | - | 0.291 *** | −0.033 | |||

| 6. C-P Conflict Index | 0.71 (.81) | - | 0.036 | ||||

| 7. Age | 16.31 (1.22) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forresi, B.; Giani, L.; Scaini, S.; Nicolais, G.; Caputi, M. The Mediation of Care and Overprotection between Parent-Adolescent Conflicts and Adolescents’ Psychological Difficulties during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Which Role for Fathers? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031957

Forresi B, Giani L, Scaini S, Nicolais G, Caputi M. The Mediation of Care and Overprotection between Parent-Adolescent Conflicts and Adolescents’ Psychological Difficulties during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Which Role for Fathers? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031957

Chicago/Turabian StyleForresi, Barbara, Ludovica Giani, Simona Scaini, Giampaolo Nicolais, and Marcella Caputi. 2023. "The Mediation of Care and Overprotection between Parent-Adolescent Conflicts and Adolescents’ Psychological Difficulties during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Which Role for Fathers?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031957

APA StyleForresi, B., Giani, L., Scaini, S., Nicolais, G., & Caputi, M. (2023). The Mediation of Care and Overprotection between Parent-Adolescent Conflicts and Adolescents’ Psychological Difficulties during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Which Role for Fathers? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031957