Parental Postnatal Depression in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Its Effects on the Parent–Child Relationship and the Child’s Developmental Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- ∎

- Studies evaluating the exposure of maternal or paternal PND on the quality of early parent–infant relationships and/or on infant/toddler outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic that include or do not include specific measures for assessing COVID-19-related experiences;

- ∎

- Studies including, or comparing, women who gave birth prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- ∎

- Cohort longitudinal studies in which at least one assessment of PND occurs within the first year postpartum and cross-sectional studies in which the assessment of PND occurs in a period that includes the first postpartum year; in the case of longitudinal studies involving assessment in pregnancy and postpartum, we considered only results related to postpartum time;

- ∎

- Studies reporting outcomes of infants/toddlers up to 36 months;

- ∎

- Studies using acceptable measures of maternal and paternal PND (including self-report scales, clinician rating scales, and structured interviews) of different aspects of the dyadic relationship and infant/toddler outcomes;

- ∎

- Conference or meeting abstracts, provided they met inclusion criteria;

- ∎

- Full-length, peer-reviewed, observational studies including cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional designs, published in English.

- ∎

- Studies including parents who sought or were in treatment for PND;

- ∎

- Studies including parents with or without a suspected COVID-19 diagnosis;

- ∎

- Studies where PND could not be distinguished from other measures (e.g., ‘psychological distress’, a composite variable combining maternal anxiety and depression);

- ∎

- Studies that did not directly and separately evaluate the effect of maternal and paternal PND on the early dyadic relationship and infant/toddler outcomes (e.g., reported on the combined effect of maternal and paternal postnatal PND and explored the effect of maternal or paternal PND on the dyadic relationship and infant/toddler outcomes as moderator or mediator of other variables);

- ∎

- Studies reporting on the neurodevelopmental outcome of infants/toddlers with a mean or median age of more than 36 months;

- ∎

- Studies conducted among a specific subset of infants not representative of the general population and with a potentially higher risk of developmental delay (e.g., studies including preterm infants, infants with low birth weight, stunted infants, or infants infected with HIV);

- ∎

- Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, nonsystematic reviews, commentaries (included only for reference checks), case studies, and randomized controlled trials.

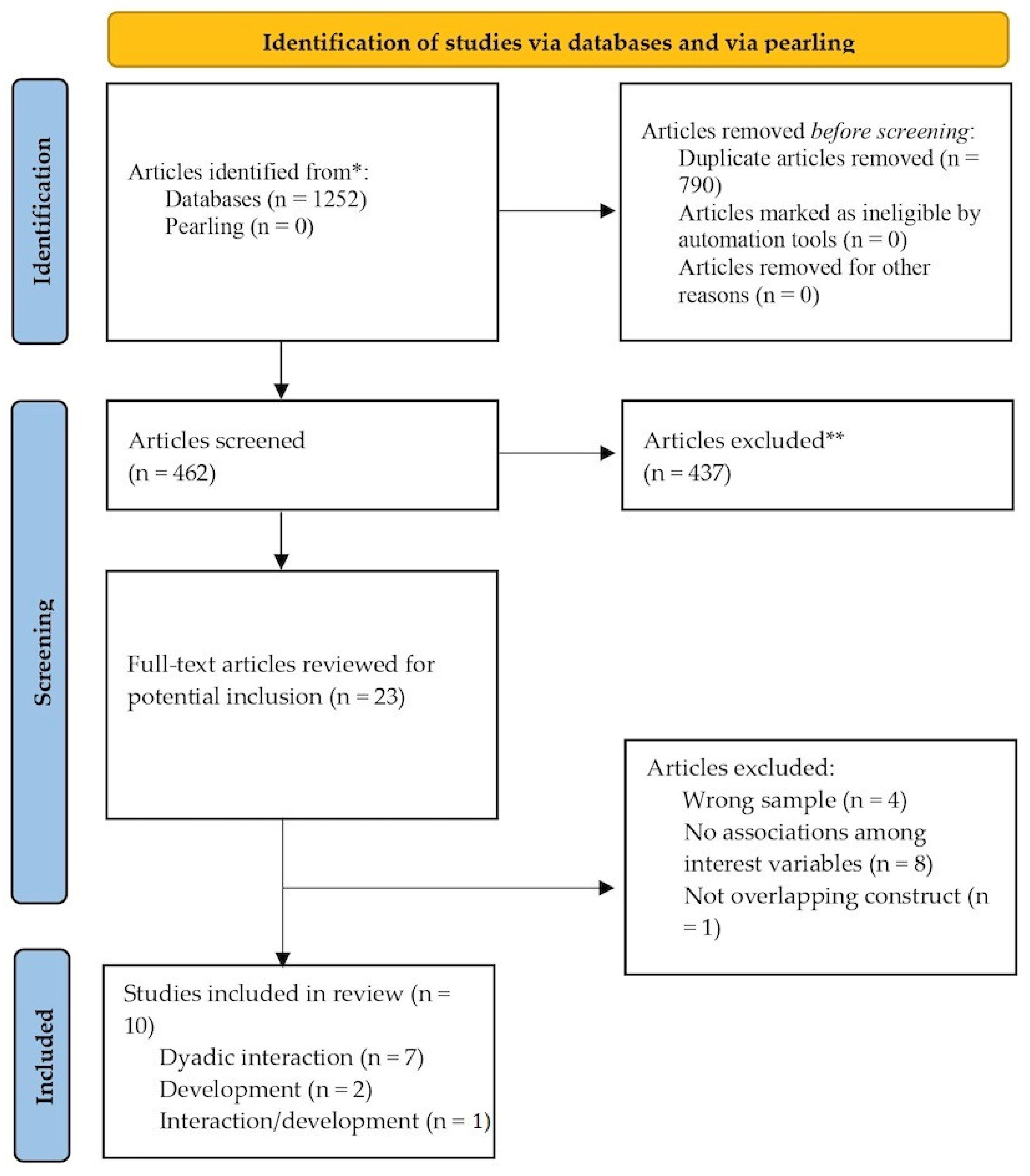

2.2. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

2.3. Quality Appraisal, Data Extraction, and Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Overview

3.2. Quality of Included Papers

| Citation (Country); Study Design | Methodological Quality | Recruitment Periods Related to Pandemic | Sample Size and Characteristics (Recruitment) | Time of Assessment PND; Tools (Referred Scores) | Time of Assessment Interaction; Tools | Results | Control for Confounding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernandes et al. [86] (Portugal) Cross-sectional | Medium | Prior to pandemic (not specified) April 30–May 21 2020 (lockdown of wave 1) | One group of 567 mothers composed of 414 who gave birth prior to the pandemic and 153 during the pandemic (online) | 0–12 months postpartum; HADS (≥11) | 0–12 months postpartum; PBQ | Giving birth during pandemic (p < 0.001), but not PND levels (p = 0.525), predicted lower levels of bonding. | No control for confounding variables. |

| Oskovi-Kaplan et al. [82] (Turkey) Cross-sectional | High | June 2020 (after wave 1) | One group of 233 mothers (maternity ward) | Within 48 h after birth; EPDS (≥13) | Within 48 h after birth; MAI | Depressed mothers showed lower levels of maternal attachment than not depressed ones (p < 0.001). | Paired by educational level, maternal age, parity, gestational week of birth, type of delivery, birthweight, and fetal gender. |

| Liu et al. [85] (United States) Cross-sectional | Medium | May 19–August 17 2020 (after wave 1) | One group of 429 mothers (online) | 6 months; CES-D (continuous scores) | 6 months; MPAS | Higher levels of PND, and concerns regarding COVID-19 pandemic, were associated with lower levels of maternal–infant attachment (p < 0.001). | Higher infant age, level of education, and household income were associated with lower levels of attachment, while first pregnancies with higher levels. Maternal age, multiparity, NICU admission, and pandemic duration were not significant. |

| Erten et al. [81] (Turkey) Cross-sectional | High | April–August, 2021 (after wave 2) | One group of 178 mothers (maternity ward) | 6 weeks; EPDS (≥13) | 6 weeks; MIBQ | Depressed mothers and not depressed ones showed similar levels of bonding (p = 0.287). | Paired by education level, maternal age, BMI, previous pregnancy, type of delivery, previous operation history, economic status, employment status, and pregnancy follow-up information; not paired by receiving guest at home during the pandemic (higher for depressed mothers). |

| Lin et al. [83] (United States) Cross-sectional | High | May 19–August 17, 2020 (after wave 1) | One group of 310 women (online) | 0–24 months postpartum; CES-D (continuous scores) | 0–24 months postpartum; PSI | PND levels contributed to parenting stress, along with concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. | Infant age, number of older children, cohabiting relationships contributed to parenting stress. Infant sex, maternal age, first pregnancy, multiparity, NICU admission, prematurity, maternal race, education, household income, pandemic duration, and anxiety symptoms did not. |

| Viaux-Savelon et al. [89] (France) Cohort longitudinal | Medium | March 27–May 5, 2020 (lockdown of wave 1) | One group of 164 mothers (T1), reduced to 138 (T2) (maternity ward) | 10 days (T1) and 6–8 weeks (T2) postpartum; EPDS (<12) | 10 days (T1) and 6–8 weeks (T2) postpartum; MIBS | Higher levels of PND at T1 (p < 0.001), but not at T2 (p = 0.32), were associated with lower level of bonding at T1 and at T2. | Maternal hypertension/preeclampsia, emergency cesarean section, neonatal complications, and threatened preterm labor were associated with higher postnatal PND symptoms. |

| Handelzalts et al. [87] (Israel) Cohort longitudinal | High | February 2018–December 2019 (T1) April 2020–January 2021 (T2) (between wave 1 and 2) | One group of 140 mothers (maternity ward) | 6 (T1) and 21 (T2) months postpartum; EPDS (continuous scores) | 6 (T1) and 21 (T2) months postpartum; PBQ | Higher levels of PND at T1 and T2 were associated with lower levels of bonding at T1 (p < 0.001) and at T2 (p < 0.001). At T2, the association between PND and bonding becomes stronger as the concern regarding the COVID-19 pandemic increases. | Age, being primiparous, higher education, having higher income level, lockdown at the time of the survey, past abortions, infertility treatments, epidural and oxytocin administration, and type of delivery were not associated with levels of bonding. |

| Harrison et al. [90] (United States) Cohort longitudinal | Medium | June 2020–February 2021 (after wave 1 and across wave 2) | One group of 125 mothers (pediatric ward) | 3 (T1) and 6 (T2) months postpartum; EPDS (continuous scores) | 3 (T1) and 6 (T2) months postpartum; items on the frequency of mother–child caretaking activities | Higher levels of PND at T1 predicted fewer recurrent mother–child caretaking activities at T2, even controlling for COVID-19 family impact. | Information not available |

| Citation (Country); Study Design | Methodological Quality | Recruitment Periods Related to Pandemic | Sample Size and Characteristics (recruitment) | Time of Assessment PND; Tools (Referred Scores) | Time of Assessment Infant Outcome; Tools | Results | Control for Confounding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papadopoulos et al. [88] (Canada) Cohort longitudinal | High | May 2020–March 2021 (after wave 2) | One group of 117 mothers (online) | 0–2 months postpartum; EPDS (≥14) | 0–2 postpartum; the Gross and Fine Motor Scales from the interRAI 0–3 Developmental Domains questionnaire | PND was a significant negative predictor of infant motor outcome (p < 0.05). | Country of residence, the month of survey completion, age, and SES were not associated with neonatal motor outcome. |

| Perez et al. [84] (Austria) Cross-sectional | High | Early 2016–early 2019 (for the control cohort) October 2020–November 2020 (for the COVID-19 cohort; wave 2) | One group of 162 mothers composed of 97 recruited prior to the pandemic and 65 during the pandemic (maternity ward) | 6–7 months postpartum; EPDS (≥13) | 6–7 months postpartum; SFS | PND had a positive, small- to medium-sized effect on sleeping/crying infant regulatory problems (p < 0.01). Moderation analysis did not show a significant relevance of being in the COVID-19 or control cohort for the association between depressive symptoms and infant crying/sleeping problems (p = 0.383). Regarding infant eating/feeding regulatory problems, there was no significant direct (p = 0.215) and interactive effect (p = 0.489) of PND. | Women with more previous children reported fewer infant crying/sleeping regulatory problems, whereas the association with infant eating/feeding problems was not significant. Infant negative emotionality was significantly associated with both infant crying/sleeping and eating/feeding problems, whereas maternal perceived social support was not. |

| Harrison et al. [90] (United States) Longitudinal | Medium | June 2020–February 2021 (after wave 1 and across wave 2) | One group of 125 mothers (pediatric ward) | 3 (T1) and 6 (T2) months postpartum; EPDS (continuous scores) | 3 (T1) and 6 (T2) months postpartum; ASQ-SE-2 | PND at 3 months significantly predicted poorer levels of infant social-emotional development at 6 months of life (p < 0.05), even after controlling for COVID-19 family impact. | Information not available. |

3.3. Association between Maternal and Paternal Postpartum Depression and Early Dyadic Relationships

3.3.1. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression and Maternal Bonding/Attachment to the Infant

3.3.2. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression and the Quality of the Parenting Experience

3.3.3. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression and Frequency of Mother–Child Caretaking Activities

3.4. Association between Maternal and Paternal Postpartum Depression and Infant or Toddler Neurodevelopment

3.4.1. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression and Infant Motor Development

3.4.2. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression and Infant Regulatory Problems

3.4.3. Association between Maternal Postpartum Depression and Infant Socio-Emotional Development

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Maternal PND during the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mother–Infant Relationship

4.2. The Effect of Maternal PND on Infant Development during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.3. The Role of Paternal PND during the COVID-19 Pandemic

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item # | Checklist Item | Reported on Page # |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives and funding | ||

| 1 | Define the indicator(s), populations (including age, sex, and geographic entities), and time period(s) for which estimates were made. | Introduction pg. 1–3 |

| 2 | List the funding sources for the work. | Funding pg. 18 |

| Data Inputs | ||

| For all data inputs from multiple sources that are synthesized as part of the study: | ||

| 3 | Describe how the data were identified and how the data were accessed. | Materials and Methods pg. 4–6; Appendix A |

| 4 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Identify all ad-hoc exclusions. | Materials and Methods pg. 3–4; Appendix B |

| 5 | Provide information on all included data sources and their main characteristics. For each data source used, report reference information or contact name/institution, population represented, data collection method, year(s) of data collection, sex and age range, diagnostic criteria or measurement method, and sample size, as relevant. | Results pg. 6–7; Table 1; Results pg. 10–11; Table 2 |

| 6 | Identify and describe any categories of input data that have potentially important biases (e.g., based on characteristics listed in item 5). | Results pg. 6–7; Results pg. 10–11; Materials and Methods pg. 5; Results pg. 6 |

| For data inputs that contribute to the analysis but were not synthesized as part of the study: | ||

| 7 | Describe and give sources for any other data inputs. | Appendix A |

| For all data inputs: | ||

| 8 | Provide all data inputs in a file format from which data can be efficiently extracted (e.g., a spreadsheet rather than a PDF), including all relevant meta-data listed in item 5. For any data inputs that cannot be shared because of ethical or legal reasons, such as third-party ownership, provide a contact name or the name of the institution that retains the right to the data. | Appendix C |

| Data analysis | ||

| 9 | Provide a conceptual overview of the data analysis method. A diagram may be helpful. | Materials and Methods pg. 4–5; Appendix A |

| 10 | Provide a detailed description of all steps of the analysis, including mathematical formulae. This description should cover, as relevant, data cleaning, data pre-processing, data adjustments and weighting of data sources, and mathematical or statistical model(s). | Materials and Methods pg. 4–5; Appendix A |

| 11 | Describe how candidate models were evaluated and how the final model(s) were selected. | N/A |

| 12 | Provide the results of an evaluation of model performance, if performed, as well as the results of any relevant sensitivity analysis. | N/A |

| 13 | Describe methods for calculating uncertainty of the estimates. State which sources of uncertainty were and were not accounted for in the uncertainty analysis. | Materials and Methods pg. 5–6 |

| 14 | State how analytic or statistical source code used to generate estimates can be accessed. | N/A |

| Results and Discussion | ||

| 15 | Provide published estimates in a file format from which data can be efficiently extracted. | Table 1 and Table 2 |

| 16 | Report a quantitative measure of the uncertainty of the estimates (e.g., uncertainty intervals). | Table 1 and Table 2 |

| 17 | Interpret results in light of existing evidence. If updating a previous set of estimates, describe the reasons for changes in estimates. | Discussion pg. 13 |

| 18 | Discuss limitations of the estimates. Include a discussion of any modelling assumptions or data limitations that affect interpretation of the estimates. | Discussion pg. 13; Limitations and Future Directions pg. 16–17; Conclusions pg. 17 |

Appendix B

| Search strategy for the impact of maternal and/or paternal postpartum depression on the quality of early reltionships (“COVID-19” OR “COVID19” OR “2019 novel coronavirus disease” OR “2019-nCoV disease” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR pandemic OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR “Wuhan coronavirus” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “Wuhan coronavirus” OR lockdown OR quarantine OR outbreak) AND ((maternal OR mother* OR wom*n) OR (paternal OR father* OR man) OR (parent*)) AND ((perinatal OR peripartum OR puerper* OR postnatal OR postpartum OR post-birth OR “after birth”) AND (depress* OR “depress* symptom*” OR “depressive disorder*” OR “affective disorder*” OR “mood disorder*” OR “maternity blues”)) AND (interaction* OR bond* OR parenting OR relationship* OR attachment OR motherhood OR fatherhood OR caregiv*) Search strategy for the impact of maternal and/or paternal postpartum depression on infant/toddler outcomes (“COVID-19” OR “COVID19” OR “2019 novel coronavirus disease” OR “2019-nCoV disease” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR pandemic OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR “Wuhan coronavirus” OR “2019-nCoV” or “novel coronavirus” OR “Wuhan coronavirus” OR lockdown OR quarantine OR outbreak) AND ((maternal OR mother* OR wom*n) OR (paternal OR father* OR man) OR (parent*)) AND ((perinatal OR peripartum OR puerper* OR postnatal OR postpartum OR post-birth OR “after birth”) AND (depress* OR “depress* symptom*” OR “depressive disorder*” OR “affective disorder*” OR “mood disorder*” OR “maternity blues”)) AND (neonate* OR infant* OR bab* OR toddler OR child* OR offspring*) AND (development* OR neurodevelopment OR motor OR language OR cognitive OR behavior OR emotional OR social-emotional OR social OR psychopatholog* OR somatic OR delay* OR risk* OR outcome* OR difficult* OR function* or growth) Filters Age: birth-36 months Publication dates: 2019–2022 Languages: English |

Appendix C

| Excluded Reference | Exclusion Reason | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chang, O.; Layton, H.; Amani, B.; Merza, D.; Owais, S.; Van Lieshout, R.J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Women Seeking Treatment for Postpartum Depression. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 9086–9092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137833. | Mothers seeking treatment for PND |

| 2 | Duguay, G.; Garon-Bissonnette, J.; Lemieux, R.; Dubois-Comtois, K.; Mayrand, K.; Berthelot, N. Socioemotional Development in Infants of Pregnant Women During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Prenatal and Postnatal Maternal Distress. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-022-00458-x | Assessment of a combined measure of anxious depressive symptoms |

| 3 | Fernandes, D.V.; Canavarro, M.C.; Moreira, H. Postpartum during COVID-19 Pandemic: Portuguese Mothers’ Mental Health, Mindful Parenting, and Mother–Infant Bonding. J. Clin. Psych. 2021, 77, 1997–2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23130. | No assessment of the impact of PND on dyadic relationships |

| 4 | Fernandes, D.V.; Canavarro, M.C.; Moreira, H. The Role of Mothers’ Self-Compassion on Mother–Infant Bonding during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study Exploring the Mediating Role of Mindful Parenting and Parenting Stress in the Postpartum Period. Infant Ment Health 2021, 42, 651–635. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21942. | No assessment of the impact of PND on dyadic relationships |

| 5 | Fernandes, D.V.; Canavarro, M.C.; Moreira, H. Self-Compassion and Mindful Parenting among Postpartum Mothers During The COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role Of Depressive and Anxious Symptoms. Current Psych. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02959-6. | PND as a mediator |

| 6 | Gonzalez-Garcia, V.; Exertier, M.; Denis, A. Anxiety, Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms, and Emotion Regulation: A Longitudinal Study of Pregnant Women Having Given Birth during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Trauma Dissoc. 2021, 5, 1002255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100225. | No associations between PND and infant/toddler outcomes |

| 7 | Kornfield, S.L.; White, L.K.; Waller, R.; Njoroge, W.; Barzilay, R.; Chaiyachati, B.H.; Himes, M.M.; Rodriguez, Y.; Riis, V.; Simonette, K.; Elovitz, M.A. Gur, R.E. Risk and Resilience Factors Influencing Postpartum Depression and Mother–Infant Bonding During COVID-19. 2021 Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1566–1574. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00803. | No assessment of the impact of PND on dyadic relationships |

| 8 | Layton, H.; Owais, S.; Savoy, C.D.; Van Lieshout, R.J. Depression, Anxiety, and Mother–Infant Bonding in Women Seeking Treatment for Postpartum Depression Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Psych. 2022, 82, 21m13874. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.21m13874. | Mothers seeking treatment for PND |

| 9 | Peng, S.; Yi, Z.; Hongyan, L.; Xiaona, H.; Douglas, J.N.; Lixia, Y.; Wei, L.; Yahiu, L.; Huaping, Z.; Li, C.; Chunhua, L.; Yang, C.; Pei, Z.; Shiwen, X.; Anuradha, N. A Multi-Center Survey on the Postpartum Mental Health of Mothers and Attachment to their Neonates during COVID-19 in Hubei Province of China. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 382. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6115. | Mothers suspected with COVID-19 compared to mothers without COVID-19 |

| 10 | van den Heuvel, M.I.; Vacaru, S.V.; Boekhorst, M.G.B.M.; Cloin, M.; van Bakel, H.; Riem, M.M.E.; de Weerth, C.; Beijers, R. Parents of Young Infants Report Poor Mental Health and more Insensitive Parenting during the First COVID-19 Lockdown. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 302, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04618-x. | No associations between PND and dyadic relationships |

| 11 | Werchan, D.; Hendrix, C.; Hume, A.M.; Zhang, M.; Thomason, M.E.; Brito, N.H. Cognitive and Socioemotional Development in Infants Exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in Utero: A Moderating Role of Prenatal Psychosocial Stress on Infant Outcomes; PsyArXiv, 2022 | Infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in utero |

| 12 | Wu, Y.; Espinosa, K.M.; Barnett, S.D.; Kapse, A.; Quistorff, J.L.; Lopez, C.; Andescavage, N.; Pradhan, S.; Lu, Y.-C.; Kapse, K.; et al. Association of Elevated Maternal Psychological Distress, Altered Fetal Brain, and Offspring Cognitive and Social-Emotional Outcomes at 18 Months. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e229244 | No assessment of PND after childbirth |

| 13 | Youji, T.; Naohisa, T.; Yuri, A.; Kazuyo, F.; Momoko, I.; Takashi, U.; Megumu, I.; Yasuo, A.; Masafumi, M.; Takahiro, N. Psychological Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on One-Month Postpartum Mothers in a Metropolitan Area of Japan. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 2021, 21, 845. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04331-1 | No assessment of the impact of PND on dyadic relationships |

Appendix D

| Study (Author, Ref) | Population Represented | Data Collection Method | Years of Data Collection | Measurement Method | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erten et al. [80] | Low-risk mothers (no high-risk pregnancies or psychiatric disease) | At maternity ward | April–August, 2021 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 178 |

| Fernandes et al. [85] | Age ≥ 18 years | Online recruitment | Prior to pandemic (not specified) 30 April –21 May 2020 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 567 |

| Handelzalts et al. [86] | Singleton birth (no preterm birth) | At maternity ward | February 2018–December 2019 April 2020–January 2021 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 140 |

| Harrison et al. [89] | N/A | At pediatric ward | June 2020–February 2021 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships and developmental outcome | 125 |

| Lin et al. [82] | Age ≥ 18 years | Online recruitment | 19 May–17 August 2020 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 310 |

| Liu et al. [84] | Age ≥ 18 years | Online recruitment | 19 May–17 August 2020 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 429 |

| Oskovi-Kaplan et al. [81] | Low-risk mothers (no high-risk pregnancies, psychiatric diseases, COVID-19 diseases during pregnancy, or a relative with COVID-19 disease) | At maternity ward | June 2020 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 233 |

| Papadopoulos et al. [87] | Age 18–55 years and singleton or multiple birth | Online recruitment | May 2020–March 2021 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for developmental outcome | 117 |

| Perez et al. [83] | Age ≥ 18 years and singleton birth (no high-risk pregnancies, substance abuse, premature birth, or low birth weight) | At maternity ward | Early 2016–early 2019 October 2020–November 2020 | Self-report for PND Parent-report developmental outcome | 162 |

| Viaux-Savelon et al. [88] | Age ≥ 18 years and post-delivery hospitalization in the conventional postnatal ward | At maternity ward | 27 March–5 May 2020 | Self-report for PND Parent-report for dyadic relationships | 164 (T1) 132 (T2) |

References

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, J.; Abeln, V.; Schneider, S.; Keller, N.; Diaz-Artiles, A.; Ramallo, M.A.; Dessy, E.; Pattyn, N.; Ferlazzo, F.; De La Torre, G.G. The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on human psychology and physical activity; a space analogue research perspective. Int. J. Astrobiol. 2022, 21, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissmath, B.; Mast, F.W.; Kraus, F.; Weibel, D. Understanding the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and containment measures: An empirical model of stress. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.M.; Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfer, R.E. The perinatal period, a window of opportunity for enhancing parent-infant communication: An approach to prevention. Child Abus. Negl. 1987, 11, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blount, A.J.; Adams, C.R.; Anderson-Berry, A.L.; Hanson, C.; Schneider, K.; Pendyala, G. Biopsychosocial Factors during the Perinatal Period: Risks, Preventative Factors, and Implications for Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ye, Z.; Fang, Q.; Huang, L.; Zheng, X. Surveillance of Parenting Outcomes, Mental Health and Social Support for Primiparous Women among the Rural-to-Urban Floating Population. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bener, A.; Sheikh, J.; Gerber, L.M. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and associated risk factors in women during their postpartum period: A major public health problem and global comparison. Int. J. Women’s Health 2012, 4, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singley, D.B.; Edwards, L.M. Men’s perinatal mental health in the transition to fatherhood. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2015, 46, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgland, V.M.E.; Moeck, E.K.; Green, D.M.; Swain, T.L.; Nayda, D.M.; Matson, L.A.; Hutchison, N.P.; Takarangi, M.K.T. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0240146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matvienko-Sikar, K.; Meedya, S.; Ravaldi, C. Perinatal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women Birth 2020, 33, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinaki, T. Maternal and Paternal Postpartum Depression: Effects on Early Infantparent Interactions. J. Pregnancy Child Health 2015, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, A.A.; Hetea, A.; Ghita, M.; Stanescu, A.M.A.; Nastasia, S.; Boghitoiu, D.; Cabinet, B.I.P. Postpartum depression in mothers and fathers—An underestimated diagnosis. Rom. Med. J. 2021, 68, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harville, E.; Xiong, X.; Buekens, P. Disasters and Perinatal Health: A Systematic Review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2010, 65, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurkiewicz, D.W.; Strzelecka, J.; Piechocka, D.I. Adverse Mental Health Sequelae of COVID-19 Pandemic in the Pregnant Population and Useful Implications for Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C.; Gillen, M.; Molina, J.A.; Wilmarth, M.J. The Social and Economic Impact of Covid-19 on Family Functioning and Well-Being: Where do we go from here? J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2022, 43, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.; Silva, R.; Franco, M. COVID-19: Financial Stress and Well-Being in Families. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 3, 1000e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J.; Aridas, A.; Tchernegovski, P.; Dudley, A.; McGillivray, J.; Reupert, A. Investigating the Impact of Isolation During COVID-19 on Family Functioning—An Australian Snapshot. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadermann, A.C.; Thomson, K.C.; Richardson, C.G.; Gagné, M.; McAuliffe, C.; Hirani, S.; Jenkins, E. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, A.; Stavridou, A.; Panagouli, E.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Spiliopoulou, C.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 17, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuczyńska, M.; Matthews-Kozanecka, M.; Baum, E. Accessibility to Non-COVID Health Services in the World During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 760795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulos, N.S.; García, M.H.; Bouchacourt, L.; Mackert, M.; Mandell, D.J. Fatherhood during COVID-19: Fathers’ perspectives on pregnancy and prenatal care. J. Men’s Health 2021, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedhofer, M.; Derksen, C.; Dietl, J.E.; Häussler, F.; Louwen, F.; Hüner, B.; Reister, F.; Strametz, R.; Lippke, S. Birthing under the Condition of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany: Interviews with Mothers, Partners, and Obstetric Health Care Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinaki, T.; Hatzidaki, E. COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Restrictions: Factors That May Affect Perinatal Maternal Mental Health and Implications for Infant Development. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 846627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lista, G.; Bresesti, I. Fatherhood during the COVID-19 pandemic: An unexpected turnaround. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 144, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwalska, J.; Napierała, M.; Bogdański, P.; Łojko, D.; Wszołek, K.; Suchowiak, S.; Suwalska, A. Perinatal Mental Health during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review and Implications for Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; McCabe, J.E. Postpartum Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, M.M.; Duffy, K.A.; Novick, A.M.; Metcalf, C.A.; Epperson, C.N. Is Postpartum Depression Different from Depression Occurring Outside of the Perinatal Period? A Review of the Evidence. Focus 2020, 18, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzi, C.W.J.B.W.M.; Jenatabadi, H.S.; Samsudin, N. Postpartum depression symptoms in survey-based research: A structural equation analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lucock, M. The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey in the UK. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norhayati, M.; Hazlina, N.N.; Asrenee, A.; Emilin, W.W. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shuai, H.; Cai, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, W.; Krabbendam, E.; Liu, S.; et al. Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.E.; Vigod, S. Postpartum Depression. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Cross, W.M.; Plummer, V.; Lam, L.; Tang, S. A systematic review of prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in Chinese immigrant women. Women Birth J. Aust. Coll. Midwives 2019, 32, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrianto, N.; Caesarlia, J.; Pajala, F.B. Depression in pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2022, 65, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, W.; Xiong, J.; Zheng, X. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Postpartum Depression during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasser, S.; Lerner-Geva, L. Focus on fathers: Paternal depression in the perinatal period. Perspect. Public Health 2018, 139, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, J.; McDermott, B.; Li, W. Risk factors for paternal perinatal depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Men Masc. 2020, 21, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalifard, M.; Payan, S.B.; Panahi, S.; Hasanpoor, S.; Kheiroddin, J.B. Paternal Postpartum Depression and Its Relationship with Maternal Postpartum Depression. J. Holist. Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 28, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser, A.K.; Ahmed, A.H.; Foli, K.J.; Coddington, J.A. Paternal Postpartum Depression: What Health Care Providers Should Know. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2013, 27, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogman, M.; Garfield, C.F.; Bauer, N.S.; Gambon, T.B.; Lavin, A.; Lemmon, K.M.; Mattson, G.; Rafferty, J.R.; Wissow, L.S.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; et al. Fathers’ Roles in the Care and Development of Their Children: The Role of Pediatricians. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.-Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.-S.; Cheng, Y. Risk assessment of paternal depression in relation to partner delivery during COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanahi, Z.; Vizheh, M.; Azizi, M.; Hajifoghaha, M. Paternal Postnatal Depression During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Health Care Providers. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.-L.; Qiu, D.; Xiao, S.-Y. Factors Influencing Paternal Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, J.; Bishop, A.; Pilkington, P.D. The longitudinal effects of paternal perinatal depression on internalizing symptoms and externalizing behavior of their children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ment. Health Prev. 2022, 26, 200230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini, H.; Nazari, M.A.; Dehghan, A.; Mirhosseini, S.; Bidaki, R.; Yazdian-Anari, P. Cognitive Behavioral Development in Children Following Maternal Postpartum Depression: A Review Article. Electron. Physician 2015, 7, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junge, C.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Slinning, K.; Polte, C.; Simonsen, T.B.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The Impact of Perinatal Depression on Children’s Social-Emotional Development: A Longitudinal Study. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 21, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fihrer, I.; McMahon, C.A.; Taylor, A.J. The impact of postnatal and concurrent maternal depression on child behaviour during the early school years. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 119, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, N.L.; Tramonte, L.; Willms, J.D. Maternal Depression, Family Functioning and Children’s Longitudinal Development. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2013, 28, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.M.; Evans, J.; Kounali, D.; Lewis, G.; Heron, J.; Ramchandani, P.G.; O’Connor, T.G.; Stein, A. Maternal Depression During Pregnancy and the Postnatal Period: Risks and Possible Mechanisms for Offspring Depression at Age 18 Years. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quevedo, L.A.; Silva, R.A.; Godoy, R.; Jansen, K.; Matos, M.B.; Pinheiro, K.A.T.; Pinheiro, R.T. The impact of maternal post-partum depression on the language development of children at 12 months. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 38, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B. Folded Futurity: Epigenetic Plasticity, Temporality, and New Thresholds of Fetal Life. Sci. Cult. 2016, 26, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchi, F.C.R.; Yao, Y.; Ward, I.D.; Ilnytskyy, Y.; Olson, D.M.; Benzies, K.; Kovalchuk, I.; Kovalchuk, O.; Metz, G.A.S. Maternal Stress Induces Epigenetic Signatures of Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases in the Offspring. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rempel, L.A.; Rempel, J.K.; Khuc, T.N.; Vui, L.T. Influence of father–infant relationship on infant development: A father-involvement intervention in Vietnam. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 1844–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, K.Y.; Haltigan, J.D.; Bahm, N.I.G. Infant attachment, adult attachment, and maternal sensitivity: Revisiting the intergenerational transmission gap. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2016, 18, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, V.; Allen, K. The Life Course Perspective Applied to Families Over Time. In Sourcebook of Family Theory and Methods: A Contextual Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; pp. 469–504. ISBN 978-0-306-44264-3. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Miranda, A.A.; King, L.M.; Salihu, H.M.; Wilson, R.E.; Nash, S.; Collins, S.L.; Berry, E.L.; Austin, D.; Scarborough, K.; Best, E.; et al. Protective Factors Using the Life Course Perspective in Maternal and Child Health. Engage 2020, 1, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeanne, K.; Sheila, P.; Spurr, S. Adult Lives: A Life Course Perspective; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4473-0043-4. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, G.H., Jr. The Life Course Paradigm: Social Change and Individual Development. In Examining Lives in Context: Perspectives on the Ecology of Human Development; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 101–139. ISBN 978-1-55798-293-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn, M.; De Graaf, P.M. Life Course Changes of Children and Well-being of Parents. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polenick, C.A.; Kim, Y.; DePasquale, N.; Birditt, K.S.; Zarit, S.H.; Fingerman, K.L. Midlife Children’s and Older Mothers’ Depressive Symptoms: Empathic Mother–Child Relationships as a Key Moderator. Fam. Relations 2020, 69, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransson, E.; Sörensen, F.; Kallak, T.K.; Ramklint, M.; Eckerdal, P.; Heimgärtner, M.; Krägeloh-Mann, I.; Skalkidou, A. Maternal perinatal depressive symptoms trajectories and impact on toddler behavior—The importance of symptom duration and maternal bonding. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 273, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.; Flanagan, J. The Maternal–Infant Bond: Clarifying the Concept. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2019, 31, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høifødt, R.S.; Nordahl, D.; Landsem, I.P.; Csifcsák, G.; Bohne, A.; Pfuhl, G.; Rognmo, K.; Braarud, H.C.; Goksøyr, A.; Moe, V.; et al. Newborn Behavioral Observation, maternal stress, depressive symptoms and the mother-infant relationship: Results from the Northern Babies Longitudinal Study (NorBaby). BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tichelman, E.; Westerneng, M.; Witteveen, A.B.; Van Baar, A.L.; Van Der Horst, H.E.; De Jonge, A.; Berger, M.Y.; Schellevis, F.G.; Burger, H.; Peters, L.L. Correlates of prenatal and postnatal mother-to-infant bonding quality: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballarotto, G.; Cerniglia, L.; Bozicevic, L.; Cimino, S.; Tambelli, R. Mother-child interactions during feeding: A study on maternal sensitivity in dyads with underweight and normal weight toddlers. Appetite 2021, 166, 105438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimino, S.; Marzilli, E.; Tafà, M.; Cerniglia, L. Emotional-Behavioral Regulation, Temperament and Parent–Child Interactions Are Associated with Dopamine Transporter Allelic Polymorphism in Early Childhood: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tissot, H.; Favez, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Despland, J.-N. Coparenting Behaviors as Mediators between Postpartum Parental Depressive Symptoms and Toddler’s Symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnig, F.; Nagl, M.; Stepan, H.; Wagner, B.; Kersting, A. Associations of postpartum mother-infant bonding with maternal childhood maltreatment and postpartum mental health: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutkiewicz, K.; Bieleninik, Ł.; Cieślak, M.; Bidzan, M. Maternal–Infant Bonding and Its Relationships with Maternal Depressive Symptoms, Stress and Anxiety in the Early Postpartum Period in a Polish Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockenberg, S.C.; Leerkes, E.M. Parental acceptance, postpartum depression, and maternal sensitivity: Mediating and moderating processes. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2010, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, A.L.B.B.; Callinan, L.S.; Smith, M.V.; Dau, A.L.B.B.; Callinan, L.S.; Smith, M.V. An examination of the impact of maternal fetal attachment, postpartum depressive symptoms and parenting stress on maternal sensitivity. Infant Behav. Dev. 2019, 54, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Wilson, A.; Guo, Y.; Lv, Y.; Yang, X.; Yu, R.; Wang, S.; Wu, Z.; et al. Postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: A structural equation model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, S.; Greca, E.; Javed, S.; Sharath, M.; Sarfraz, Z.; Sarfraz, A.; Salari, S.W.; Hussaini, S.S.; Mohammadi, A.; Chellapuram, N.; et al. Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211059348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.A.; Alkema, L.; Black, R.E.; Boerma, J.T.; Collins, G.S.; Ezzati, M.; Grove, J.T.; Hogan, D.R.; Hogan, M.C.; Horton, R.; et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: The GATHER statement. Lancet 2016, 388, e19–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetic, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. Joanna Briggs Inst. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, O.; Biyik, I.; Soysal, C.; Ince, O.; Keskin, N.; Tascı, Y. Effect of the Covid 19 pandemic on depression and mother-infant bonding in uninfected postpartum women in a rural region. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskovi-Kaplan, Z.A.; Buyuk, G.N.; Ozgu-Erdinc, A.S.; Keskin, H.L.; Ozbas, A.; Tekin, O.M. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic and Social Restrictions on Depression Rates and Maternal Attachment in Immediate Postpartum Women: A Preliminary Study. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-C.; Zehnah, P.L.; Koire, A.; Mittal, L.; Erdei, C.; Liu, C.H. Maternal Self-Efficacy Buffers the Effects of COVID-19–Related Experiences on Postpartum Parenting Stress. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 51, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.; Göbel, A.; Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Schepanski, S.; Singer, D.; Bindt, C.; Mudra, S. Born Under COVID-19 Pandemic Conditions: Infant Regulatory Problems and Maternal Mental Health at 7 Months Postpartum. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 805543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.H.; Hyun, S.; Mittal, L.; Erdei, C. Psychological risks to mother–infant bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 91, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, D.V.; Canavarro, M.C.; Moreira, H. Postpartum during COVID-19 pandemic: Portuguese mothers’ mental health, mindful parenting, and mother–infant bonding. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 1997–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelzalts, J.E.; Hairston, I.S.; Levy, S.; Orkaby, N.; Krissi, H.; Peled, Y. COVID-19 related worry moderates the association between postpartum depression and mother-infant bonding. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Nichols, E.S.; Mohsenzadeh, Y.; Giroux, I.; Mottola, M.F.; Van Lieshout, R.J.; Duerden, E.G. Prenatal and postpartum maternal mental health and neonatal motor outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2022, 10, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaux-Savelon, S.; Maurice, P.; Rousseau, A.; Leclere, C.; Renout, M.; Berlingo, L.; Cohen, D.; Jouannic, J.-M. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on maternal psychological status, the couple’s relationship and mother-child interaction: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.; Rohde, J.; Hatchimonji, D.; Berman, T.; Flatley, C.A.; Okonak, K.; Cutuli, J.J. Postpartum Mental Health and Infant Development During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2022, 149, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of Postnatal Depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockington, I.F.; Oates, J.; George, S.; Turner, D.; Vostanis, P.; Sullivan, M.; Loh, C.; Murdoch, C. A Screening Questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2001, 3, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaré, B.; Fonseca, A.; Canavarro, M.C. Avaliação da ligação parental ao bebé após o nascimento: Análise fatorial confirmatória da versão portuguesa do Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ). Laboratório Psicol. 2013, 10, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienfait, M.; Maury, M.; Haquet, A.; Faillie, J.-L.; Franc, N.; Combes, C.; Daudé, H.; Picaud, J.-C.; Rideau, A.; Cambonie, G. Pertinence of the self-report mother-to-infant bonding scale in the neonatal unit of a maternity ward. Early Hum. Dev. 2011, 87, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Atkins, R.; Kumar, R.; Adams, D.; Glover, V. A new Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: Links with early maternal mood. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2005, 8, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.L.; Babcock, S.E.; Li, Y.; Dave, H.P. A psychometric evaluation of the interRAI Child and Youth Mental Health instruments (ChYMH) anxiety scale in children with and without developmental disabilities. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groß, S.; Reck, C.; Thiel-Bonney, C.; Cierpka, M.M. Empirische Grundlagen des Fragebogens zum Schreien, Füttern und Schlafen (SFS). Prax. der Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2013, 62, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, J.; Bricker, D.; Twombly, E.; Yockelson, S.; Davis, M.; Kim, Y. Ages & Stages Questionnaires, Social-Emotional (ASQ: SE): A Parent-Completed, Child-Monitoring System for Social-Emotional Behaviors; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Moehler, E.; Brunner, R.; Wiebel, A.; Reck, C.; Resch, F. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother–child bonding. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2006, 9, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonnenmacher, N.; Noe, D.; Ehrenthal, J.C.; Reck, C. Postpartum bonding: The impact of maternal depression and adult attachment style. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocknek, E.L.; Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Fitzgerald, H.; Burns-Jager, K.; Carolan, M.T. Maternal Psychological Absence and Toddlers’ Social-Emotional Development: Interpretations from the Perspective of Boundary Ambiguity Theory. Fam. Process. 2012, 51, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Eidelman, A.I. Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant–mother and infant–father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal vagal tone. Dev. Psychobiol. 2007, 49, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennell, J.; McGrath, S. Starting the process of mother-infant bonding. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 94, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Vismara, L. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women’s Mental Health during Pregnancy: A Rapid Evidence Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Shrestha, A.D.; Stojanac, D.; Miller, L.J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2020, 23, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottemanne, H.; Vahdat, B.; Jouault, C.; Tibi, R.; Joly, L. Becoming a Mother During COVID-19 Pandemic: How to Protect Maternal Mental Health Against Stress Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 7642647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostacoli, L.; Cosma, S.; Bevilacqua, F.; Berchialla, P.; Bovetti, M.; Carosso, A.R.; Malandrone, F.; Carletto, S.; Benedetto, C. Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Kunz, E.; Schweyer, D.; Eickhorst, A.; Cierpka, M. Links between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms, maternal distress, infant gender and sensitivity in a high-risk population. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2011, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, C.L.; Stowe, Z.N.; Newport, D.J.; Brennan, P.A. Physiological attunement in mother–infant dyads at clinical high risk: The influence of maternal depression and positive parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 30, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi, C.; Ricca, V.; Wilson, A.; Homer, C.; Vannacci, A. Previous psychopathology predicted severe COVID-19 concern, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in pregnant women during “lockdown” in Italy. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2020, 23, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaux, S.; Maurice, P.; Cohen, D.; Jouannic, J. Giving birth under lockdown during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, M.; Mettler, T.; Osma, J. Health professionals’ perspective on the promotion of e-mental health apps in the context of maternal depression. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diego, M.A.; Field, T.; Hernandez-Reif, M. Prepartum, postpartum and chronic depression effects on neonatal behavior. Infant Behav. Dev. 2005, 28, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutra, K.; Chatzi, L.; Bagkeris, M.; Vassilaki, M.; Bitsios, P.; Kogevinas, M. Antenatal and postnatal maternal mental health as determinants of infant neurodevelopment at 18 months of age in a mother–child cohort (Rhea Study) in Crete, Greece. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchi, C.; De Carli, P.; Vieno, A.; Piallini, G.; Zoia, S.; Simonelli, A. Does infant negative emotionality moderate the effect of maternal depression on motor development? Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 119, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ölmestig, T.K.; Siersma, V.; Birkmose, A.R.; Kragstrup, J.; Ertmann, R.K. Infant crying problems related to maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffol, E.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Lahti, J.; Lipsanen, J.; Heinonen, K.; Pesonen, A.-K.; Hämäläinen, E.; Kajantie, E.; Laivuori, H.; Villa, P.M.; et al. Maternal depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy are associated with poorer sleep quantity and quality and sleep disorders in 3.5-year-old offspring. Sleep Med. 2018, 56, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, B.; Lachmann, F.M. Co-constructing inner and relational processes: Self- and mutual regulation in infant research and adult treatment. Psychoanal. Psychol. 1998, 15, 480–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Grumi, S.; Altieri, L.; Bensi, G.; Bertazzoli, E.; Biasucci, G.; Cavallini, A.; Decembrino, L.; Falcone, R.; Freddi, A.; et al. Prenatal maternal stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and infant regulatory capacity at 3 months: A longitudinal study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, E.; Lewis, A.J.; Watson, S.J.; Galbally, M. Perinatal maternal mental health and infant socio-emotional development: A growth curve analysis using the MPEWS cohort. Infant Behav. Dev. 2019, 57, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaever, M.S.; Krogh, M.T.; Smith-Nielsen, J.; Christensen, T.T.; Tharner, A. Infants of Depressed Mothers Show Reduced Gaze Activity During Mother-Infant Interaction at 4 Months. Infancy 2015, 20, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, A.; Prasad, R.; Ahmed, S.; Rao, N.P. Effect of gender and clinical-financial vulnerability on mental distress due to COVID-19. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2020, 23, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, P.; Li, T.M.; Chan, K.L.; Ting, A.Y.Y.; Chan, C.Y.; Koh, Y.W.; Ho, F.K.W.; Lee, A. Associations of paternal postpartum depressive symptoms and infant development in a Chinese longitudinal study. Infant Behav. Dev. 2018, 53, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethna, V.; Murray, L.; Netsi, E.; Psychogiou, L.; Ramchandani, P.G. Paternal Depression in the Postnatal Period and Early Father–Infant Interactions. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaslow, M.J.; Pedersen, F.A.; Cain, R.L.; Suwalsky, J.T.; Kramer, E.L. Depressed mood in new fathers: Associations with parent-infant interaction. Genet. Social Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 1985, 111, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, F.; Pittelkow, M.-M.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Garthus-Niegel, S. The Relationship Between Paternal and Maternal Depression During the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 563287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnet, K.; Wouters, E.; Mortelmans, D.; Pasteels, I.; De Backer, C.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Van Hiel, A. The Influence of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting Stress and Depressive Symptoms on Own and Partner’s Parent-Child Communication. Fam. Process. 2012, 52, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, R.W.; Saldanha, I.J. How should systematic reviewers handle conference abstracts? A view from the trenches. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Federica, G.; Renata, T.; Marzilli, E. Parental Postnatal Depression in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Its Effects on the Parent–Child Relationship and the Child’s Developmental Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032018

Federica G, Renata T, Marzilli E. Parental Postnatal Depression in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Its Effects on the Parent–Child Relationship and the Child’s Developmental Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032018

Chicago/Turabian StyleFederica, Genova, Tambelli Renata, and Eleonora Marzilli. 2023. "Parental Postnatal Depression in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Its Effects on the Parent–Child Relationship and the Child’s Developmental Outcomes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032018

APA StyleFederica, G., Renata, T., & Marzilli, E. (2023). Parental Postnatal Depression in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Its Effects on the Parent–Child Relationship and the Child’s Developmental Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032018