Public Policies for Fluoride Use in Colombia and Brazil before and during the Adoption of the Right to Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

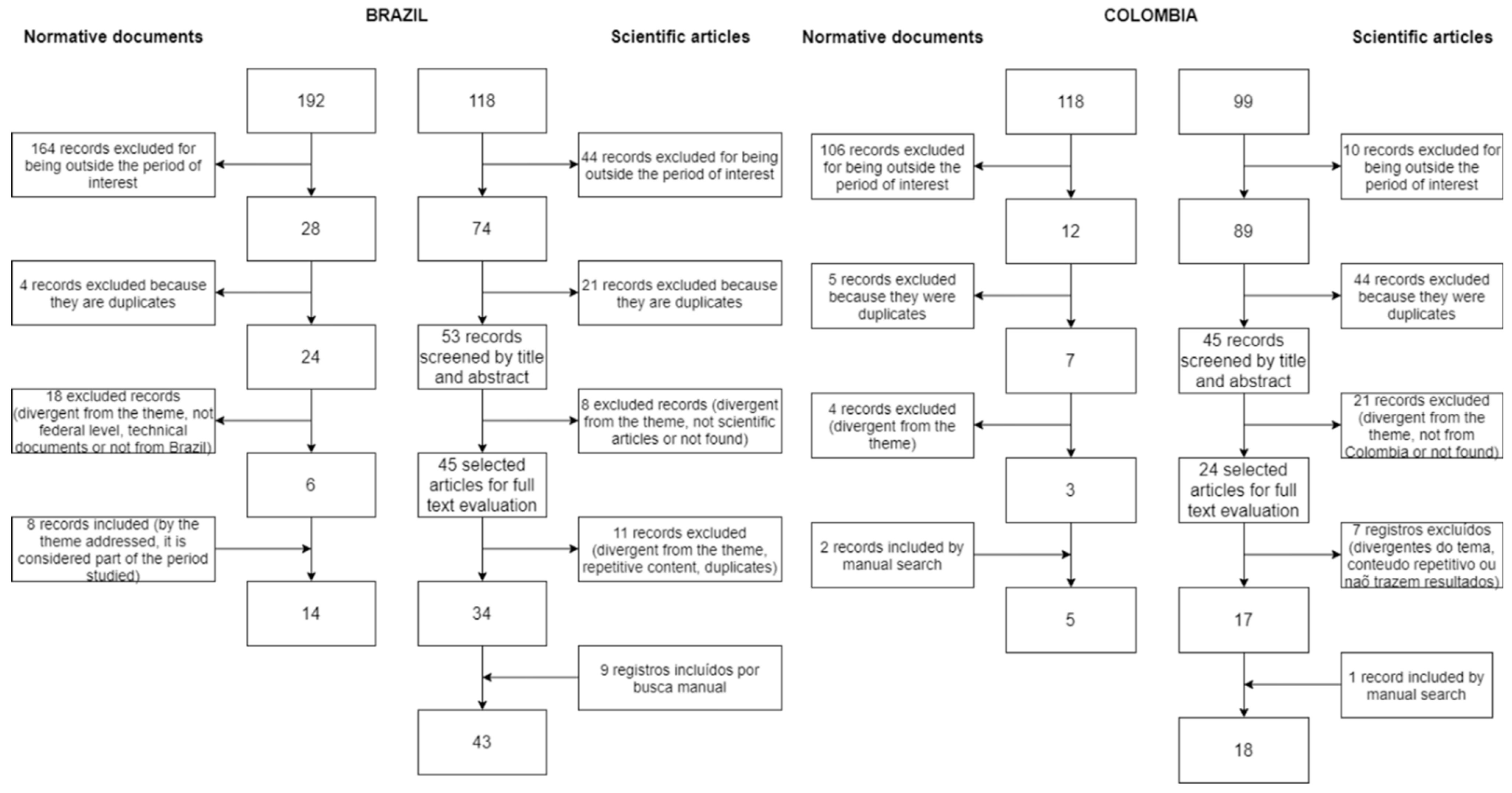

2. Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Colombia

3.2. Brazil

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Follow-up to the political declaration of the third high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable disease. In Proceedings of the Seventy-Fifth World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 22–28 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P.; Singh, S.; Mathur, A.; Makkar, D.K.; Aggarwal, V.P.; Batra, M.; Sharma, A.; Goyal, N. Impact of dental disorders and its influence on self-esteem levels among adolescents. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC05–ZC08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvai, P.C. Cárie dentária e flúor: Uma relação do século XX. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2000, 5, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whelton, H.P.; Spencer, A.J.; Do, L.G.; Rugg-Gunn, A.J. Fluoride revolution and dental caries: Evolution of policies for global use. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mullane, D.M.; Baez, R.J.; Jones, S.; Lennon, M.A.; Petersen, P.E.; Rugg-Gunn, A.J.; Whelton, H.; Whitford, G.M. Fluoride and oral health. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33, 69–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frazão, P. The use of fluorides in public health: 65 years of history and challenges from Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OPS—Organización Panamericana de la Salud; Salud Internacional. Un Debate Norte-Sur; OPS: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, C.A.P. Ideias, conhecimento e políticas públicas: Um inventário sucinto das principais vertentes analíticas recentes. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Soc. 2003, 18, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nutley, S.; Webb, J. Evidence and the policy process. In What Works? Evidence-Based Policy and Practice in Public Services; Davies, H.T.O., Nutley, S.M., Smith, P.C., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm. Rev. 1979, 39, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, D. Salt fluoridation: An alternate measure to water fluoridation. Int. Dent. J. 1967, 17, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rozo, G.J. Informe evaluativo de un programa continuado de adición de fluoruro de sodio en un barrio de Bogotá, D.E. Rev. Fed. Odontol. Colomb. 1969, 18, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, R.; Espinal, F.; Vélez, H.; Vélez, A. Comunidad Colombiana con baja prevalencia de caries, sin antecedentes de flúor. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1969, 66, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vélez, A.; Espinal, F.; Mejía, R.; Vélez, H. Un sistema económico de fluoruración del agua en comunidades rurales. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1970, 68, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, D.; Gillespie, G.M.; Vélez, H. Estudio sobre la fluoruración de la sal. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1972, 73, 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K.J.; Glass, R.L.; Espinal, F.; Velez, H. Caries-free teeth in the absence of the fluoride ion. J. Public Health Dent. 1972, 32, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez, H.; Espinal, F.; Hernández, N.; Mejía, R. Fluoruración de la sal en cuatro comunidades colombianas. III. Estudio del crecimiento y desarrollo. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1973, 74, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, R.L.; Rothman, K.J.; Espinal, F.; Vélez, H.; Smith, N.J. The prevalence of human dental caries and water-borne trace metals. Arch. Oral Biol. 1973, 18, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, N.; Espinal, F.; Mejía, R.; Vélez, H. Fluoruración de la sal en cuatro comunidades colombianas. IV. Encuesta dietética en Armenia y Montebello. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1973, 75, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernández, N.; Espinal, F.; Mejía, R.; Vélez, H. Fluoruración de la sal en cuatro comunidades colombianas. V. Encuesta dietética en Don Matías y San Pedro. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1974, 76, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, N.; Espinal, F.; Mejía, R.; Vélez, H. Fluoruración de la sal en cuatro comunidades colombianas. VI. Ingesta de sal. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1974, 77, 298–299. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, R.; Espinal, F.; Vélez, H.; Aguirre, S.M. Fluoruración de la sal en cuatro comunidades colombianas. VIII. Resultados obtenidos de 1964 a 1972. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1976, 73, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Marthaler, T.M.; Mejía, R.; Tóth, K.; Viñes, J.J. Caries-preventive salt fluoridation. Caries Res. 1978, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herazo-Acuña, B.J. Consideraciones sobre atención primaria en salud oral. Rev. Fed. Odontol. Colomb. 1982, 30, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herazo-Acuña, B.J.; Salazar-Oliveros, L. Antecedentes generales de programas preventivos de salud oral en la República de Colombia. Rev. Fed. Odontol. Colomb. 1983, 32, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Herazo-Acuña, B.J. Flúor. Rev. Fed. Odontol. Colomb. 1984, 148, 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Herazo-Acuña, B.J.; Salazar-Oliveros, L. Producción de fluoruros en Colombia. Rev. Fed. Odontol. Colomb. 1985, 34, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Calle, G.; Toro, G.; Rubio, C.A.; Bojanini, J.; Arias, O. Situación de salud oral de Medellín. 20 años de prevención integral. CES Odontol. 1990, 3, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, R.; Agualimpia, C.; Torres, J.; Galán, R.; Rodríguez, W. Morbilidad oral. In Investigación Nacional de Morbilidad. Estudio de Recursos Humanos para la Salud y la Educación Médica en Colombia; MINSALUD, ASCOFAME: Bogotá, Colombia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Resolution 2772 of March 27, 1978; Ministry of Health: Bogota, Colombia, 1978.

- Law 9 of January 24, 1979; Diario Oficial de Colombia; Congress of Colombia: Bogota, Colombia, 1979.

- Decree 2105 of July 26, 1983; Diario Oficial de Colombia; Ministry of Health: Bogota, Colombia, 1983.

- Decree 1594 of June 26, 1984; Diario Oficial de Colombia; Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Health: Bogota, Colombia, 1984.

- Decree 2024 of August 21, 1984; Diario Oficial de Colombia; Ministry of Health and Ministry of Economic Development: Bogota, Colombia, 1984.

- Freire, P.S. Planning and conducting an incremental dental program. JADA 1964, 68, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, C.F. Alguns aspectos da prevenção da cárie dentária no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Odontol. 1966, 25, 295–321. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, Y. Efeito inibidor de cárie dental de uma única aplicação tópica de solução de fluorfosfato acidulada em adultos jovens. Experiência de um ano. Rev. Saúde Pública 1970, 4, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, Y.; Viegas, A.R. Análise dos dados de prevalência de cárie dental na cidade de Campinas, SP, Brasil, depois de dez anos de fluoração da água de abastecimento público. Rev. Saúde Pública 1974, 8, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, H.S.; Heifetz, S.B.; McClendon, B.J.; Viegas, A.R.; Guimarães, L.O.; Lopes, E.S. Evaluation of self-administered prophylaxis and supervised toothbrushing with acidulated phosphate fluoride. Caries Res. 1974, 8, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinplastch, B.S. Fluoretação de águas no Brasil. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1974, 76, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Cardoso, M.H.; Andrade, J.L.R. Alguns aspectos da fluorose dentária. Rev. Fac. Odontol. São Paulo 1975, 13, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, O.; Saliba, N.A.; Novaes, A. Contribuição ao estudo da determinação do íon fluoreto, existente na água, dos sistemas públicos de abastecimento de água. Estomatol. Cult. 1975, 9, 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T. Estudo comparativo da prevalência de cárie, em dentes permanentes, de escolares residentes em regiões com alto e baixo teor de flúor. Rev. Fac. Odontol. São Paulo 1975, 13, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freire, A.S. A fluoretação da água em Cachoeiro do Itapemirim: Seus resultados após seis anos de operação. Rev. Gaucha Odontol. 1976, 24, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, N.A.; Saliba, O. Contribuição ao estudo sobre a eficiência da aplicação tópica de uma solução acidulada de flúor e fosfato. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1977, 82, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rocca, R.A.; Vertuan, V.; Mendes, A.J.D. Efeito da ingestão de água fluoretada na prevalência de cárie e perda de primeiros molares permanentes. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1979, 33, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alcaide, A.L.; Veronezi, O. Prevalencia de fluorose dental na cidade de Icém. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1979, 33, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, J.; Cardoso, J.S. Sistemas de fluoretação de água em Juazeiro (BA) e Petrolina (PE). Estudo comparativo de alguns resultados epidemiológicos. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1979, 33, 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, L.O.C.; Moreira, B.W.; Vieira, S.; Piedade, E.F. Prevenção da cárie dentária: Aplicação tópica de fluoreto de sódio acidulado associada à fluoretação das águas de abastecimento público. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1980, 34, 500–505. [Google Scholar]

- Cury, J.A.; Guimarães, L.O.C.; Arbex, S.T.; Moreira, B.H.W. Análise de dentifrícios fluoretados: Concentração e formas químicas de fluoretos encontrados em produtos brasileiros. Rev. Assoc.Paul. Cir. Dent. 1981, 35, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moitta, F. Situação atual da fluoretação das águas de abastecimento público no Brasil. Rev. Fund. SESP 1981, 26, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, I.C. Atualização tecnológica dos procedimentos odontológicos, Pará, Brasil. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1982, 93, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, R.G.; de Araújo, H.V.; de Albuquerque, A.J. Desenvolvimento de uma técnica simplificada de fluoretação de águas para comunidades de pequeno porte. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1982, 92, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vasconcellos, M.C.C. Prevalência de cárie dentária em escolares de 7 a 12 anos de idade, na cidade de Araraquara, SP (Brasil), 1979. Rev. Saúde Pública 1982, 16, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinto, V.G. Prevenção da cárie dental: A questão da fluoretação do sal. Rev. Saúde Pública 1982, 16, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buendia, O.C. Situação atual da fluoretação de águas de abastecimento público no Estado de São Paulo-Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública 1983, 17, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.G. Saúde bucal no Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública 1983, 17, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buendia, O.C. Fluoretação de águas de abastecimento público no Brasil. (Atualização). Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1984, 38, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, Y.; Viegas, A.R. Análise dos dados de prevalência de cárie dental na cidade de Barretos, SP, Brasil, depois de dez anos de fluoretação da água de abastecimento público. Rev. Saúde Pública 1985, 19, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lacerda, J.L.S. Os primeiros resultados da fluoretaçäo de águas em abastecimentos públicos em Minas Gerais. Rev. Fund. SESP 1985, 30, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, J.R.M.; Bassani, A.C.; Lopes, E.S. Prescrição de flúor para gestantes e crianças. RGO 1985, 33, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, Y.; Viegas, A.R. Prevalência de cárie dental na cidade de Campinas, SP, Brasil, depois de quatorze anos de fluoraçäo da água de abastecimento pública. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1985, 39, 272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, L.H.P.M.; Parreira, M.L.J.; Ribeiro, J.C.C. Prevalência de cárie em dentes decíduos de escolares beneficiados e não pelos fluoretos. Arq. Centro Estud. Curso Odontol. 1985, 22, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, J.R.M. Suplementação de flúor no Brasil. Pediatr. Mod. 1985, 20, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- De Pretto, P.W.; Dias, O.M.L.; Lopes, E.S.; Bastos, J.R.M. Redução de cárie dentária em escolares de Bauru, após oito anos de fluoretação de água de abastecimento público. Estomatol. Cult. 1985, 15, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cury, J.A. Estabilidade do flúor nos dentifrícios brasileiros. RGO 1986, 34, 430–432. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, R.N.; Cury, J.A. Reatividade dos dentifrícios fluoretados comercializados no Brasil com o esmalte dental humano. RGO 1986, 34, 381–383. [Google Scholar]

- Vertuan, V. Redução de cáries com água fluoretada: Após 19 anos de fluoretação das águas de abastecimento de Araraquara-São Paulo-Brasil. RGO 1986, 34, 469–471. [Google Scholar]

- Zamorano, W.M.C.; Parreira, M.L.J.; Ribeiro, J.C.C. Estudo comparativo da prevalência de lesão cariosa em dentes permanentes, com variações do teor de flúor na água de abastecimento público, nas cidades de Belo Horizonte e Rio Acima-MG. Arq. Centro Estud. Curso Odontol. 1987, 24, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, A.R.; Viegas, I.; Castellanos-Fernández, R.A.; Rosa, A.G.F. Fluoretação da água de abastecimento público. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1987, 41, 202–204. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre dos Santos, M.; Cury, J.A. Dental plaque fluoride is lower after discontinuation of water fluoridation. Caries Res. 1988, 22, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cury, J.A. Dentifrícios antiplaca no Brasil: Avaliação do flúor. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 1988, 42, 168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, Y.; Viegas, A.R. Prevalência de cárie dental em Barretos, SP, Brasil, após dezesseis anos de fluoretação da água de abastecimento público. Rev. Saúde Pública 1988, 22, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopes, T.S.P.; Parreira, M.L.J.; Carvalho, P.V. Prevalência de lesão cariosa em primeiros molares permanentes de escolares residentes em regiões com flúor e sem flúor na água de abastecimento. (Estudo comparativo baseado em exames clínico e radiográfico). Arq. Centro Estud. Curso Odontol. 1988, 25/26, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Arcieri, R.M.; Carvalho, M.d.L.; Goncalves, L.M.; de Almeida, H.A.; Marra, E.M.; Ferreira, A.L. Redução da cárie dentária após dois anos da associação de bochechos e aplicações tópicas com flúor. Rev. Centro Cienc. Biomed. Univ. Fed. Uberlandia 1988, 4, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neder, A.C.; Manfredini, M.A. Sobre a oportunidade de fluoretaçäo do sal no Brasil: A modernidade do atraso. Saúde Debate 1991, 32, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.F.A. O problema da fluoretação do sal no Brasil. RGO 1991, 39, 306–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ordinance 33 of May 28, 1968; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1968.

- Law 6.050 of May 24, 1974; Official Gazette of the Union; National Congress: Brasília, Brazil, 1974.

- Decree 76.872 of December 22, 1975; Official Gazette of the Union; Presidency of the Republic: Brasília, Brazil, 1975.

- Ordinance 635 of December 26, 1975; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1975.

- Decree 90.892 of February 1, 1985; Official Gazette of the Union; Presidency of the Republic: Brasília, Brazil, 1985.

- Law 7.486 of June 6, 1986; Official Gazette of the Union; Presidency of the Republic: Brasília, Brazil, 1986.

- Ordinance 21 of October 25, 1989; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1989.

- Ordinance 22, December 20, 1989; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1989.

- Ordinance 1437 of December 14, 1990; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1990.

- Ordinance 101 of January 31, 1991; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1991.

- Ordinance 1 of February 5, 1991; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1991.

- Ordinance 2 of February 28, 1991; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1991.

- Ordinance 3 of August 13, 1991; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1991.

- Ordinance 851 of August 4, 1992; Official Gazette of the Union; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 1992.

- Beltrán-Aguilar, E.D.; Estupiñán-Day, S.; Báez, R. Analysis of prevalence and trends of dental caries in the Americas between the 1970s and 1990s. Int. Dent. J. 1999, 49, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvai, P.C.; Frazão, P.; Roncalli, A.G.; Antunes, J.L.F. Cárie dentária no Brasil: Declínio, iniquidade e exclusão social. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2006, 19, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suárez-Zúñiga, E.; Velosa-Porras, J. Comportamiento epidemiológico de la caries dental en Colombia. Univ. Odontol. 2013, 32, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.J. Appropriate Use of Fluorides for Human Health; Murray, J.J., Ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J. De Roosevelt, mas também de Getúlio: O Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública. Hist. Cienc. Saúde Manguinhos 2007, 14, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rodríguez, J.C.; Olivera, M.J.; Padilla-Herrera, M.C. Epidemiological evolution and historical anti-malarial control initiatives in Colombia, 1848–2019. Infez. Med. 2022, 30, 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Eslava, J.C. El influjo norteamericano en el desarrollo de la salud pública en Colombia. Biomédica 1998, 18, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guzmán, M.P.; Quevedo, E. La cooperación técnica norteamericana en salud pública en Colombia durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Biomédica 1999, 19, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shipman, H.R.; Chaves, M.M. La fluoruración del agua en la América Latina y en el Caribe, con especial referencia al empleo de espatoflúor. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam. 1962, 53, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ávila, L.S.; Andrade, E.I.G.; Aith, F.M.A. A judicialização da saúde no Brasil e na Colômbia: Uma discussão à luz do novo constitucionalismo latino-americano. Saúde Soc. 2020, 29, e190424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, M.; Quevedo, E. The birth of a Ministry of Public Health in Colombia, 1946–1953: Cold War, invisible government and asymmetrical interdependence. Hist. Cienc. Saúde Manguinhos 2022, 29, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, S. Brazil’s health-care reform: Social movements and civil society. Lancet 2011, 377, 1724–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brazil | Colombia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database | Search Keywords | Records | Search Keywords | Records |

| BVS | flúor AND Brasil | 56 | flúor AND Colombia | 38 |

| LILACS | flúor OR fluoretos [Palavras] and políticas OR programas [Palavras] and Brasil [Palavras] | 46 | flúor OR fluoruros [Palavras] and políticas OR programas [Palavras] and Colombia [Palavras] | 11 |

| PubMed | (fluor*) AND (dental health) AND (Brazil) | 10 | (fluorine OR fluorides) AND (Colombia) | 27 |

| SciELO | fluor* AND Brasil | 5 | fluor* AND Colombia | 0 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (fluorine OR fluorides) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (policy OR program) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (brazil)) AND PUBYEAR > 1959 AND PUBYEAR < 1989 | 1 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (fluorine OR fluorides) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (colombia)) AND PUBYEAR > 1959 AND PUBYEAR < 1992 | 23 |

| Total | 118 | 99 | ||

| Brazil | Colombia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Source | Search Strategies | Records | Information Source | Search Strategies | Records |

| Planalto | Advanced search with terms: flúor, fluoreto | 35 | Ministry of Health and Social Protection | Normativa (Manual search in ascending chronological order) | 7 |

| SAÚDE LEGIS | Topic: Flúor | 4 | SUIN JURISCOL | “sal para consumo humano” + Filter: Salud y protección social | 2 |

| SAÚDE LEGIS | Topic: Fluoretação | 8 | INVIMA | Normatividad/Índice por temas/Cosméticos (Manual search in ascending chronological order) | 32 |

| SAÚDE LEGIS | Topic: Qualidade da água | 18 | INVIMA | Normatividad/Índice por temas/Sal | 2 |

| SAÚDE LEGIS | Topic: Fluor | 15 | INVIMA | Normatividad/Búsqueda avanzada/texto: dentríficos | 12 |

| SICON | Fluoretação Filters: Gestão de Normas Jurídicas (Legislação Federal); Repositório de Documentos Legislativos | 2 | INVIMA | Normatividad/Búsqueda avanzada/texto: dentífricos | 6 |

| BVSMS | Legislação da Saúde/Legislação Básica do SUS | 9 | INVIMA | Normatividad/Búsqueda avanzada/texto: “enjuagues bucales” | 10 |

| BVSMS | fluoretos (Filter: Base de dados: Ministério da saúde) | 4 | INVIMA | Normatividad/Índice por temas/Agua | 14 |

| BVSMS | fluoretação (Filter: Data base: Ministry of Health) | 9 | INS | IQEN (Manual search in chronological order) | 4 |

| BVSMS | (flúor) AND (dentifrício) OR (enxaguatório) OR (verniz) + Filter: portuguese. Data base: Ministry of Health | 11 | INS | Technical-scientific publications/protocols and notification sheets/Event: Fluoride exposition | 6 |

| ANVISA | Portal ANVISA/Legislation/dental hygiene; tipo de atos: Todos; Topics: Cosméticos | 45 | INS | Manual search | 3 |

| ANVISA | Thematic Libraries: *Alimentos (água envasada) | 4 | RID | Searches with key-words (flúor, fluoruro, sal) | 20 |

| ANVISA | Thematic Libraries: *Cosméticos (dentifrícios e enxaguatórios bucais) | 26 | |||

| FUNASA | Portarias FUNASA (manual search in ascending chronological order) | 2 | |||

| Total | 192 | Total | 118 | ||

| Author–Year | Study Design/Vehicle | Aim | Methods/Development | Results/Final Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrepo, D. (1967) [12] | Review/Salt | To show salt fluoridation as an alternative to water fluoridation. | The pioneering study in Colombia is described with its objectives, methods and preliminary results. | Fluoridated salt is presented as a viable method for communities and regions where the water system does not allow for the implementation of fluoridation processes due to the high cost or lack thereof. Fluoridated salt can reach rural areas easily and at a minimal cost; the processes are simple, safe and low-cost. A uniform mixture of salt and fluoride was achieved, the average daily salt consumption was established to calculate the fluoride dose and annual studies will show the effectiveness of the method against caries. |

| Rozo, G.J. (1969) [13] | Effectiveness study/Water | To show the evaluation of a program to add sodium fluoride to the water supply system of a Bogota neighborhood. | The background and circumstances that have caused the city to suspend water fluoridation are analyzed. The DMF of Bogota in 1962 (before water fluoridation) and of Santa Isabel (Bogota district) in 1968 (6 years after water fluoridation) were compared with the data of Cachipay (rural area without fluoride in the water) in 1968. | There was a 45% decrease in dental caries after 6 years of continuous application of sodium fluoride in water. |

| Mejía et al. (1969) [14] | Dental caries prevalence study/Water | To describe the results of a study in which the low prevalence of caries in a community is not attributable to fluoride, since it was not added to the water and the content of it in natural water was negligible. | In 1966, an epidemiological caries survey was conducted in Heliconia, which included all school children aged 8–14 years (n = 267). The DMFT and dmf indices were used. | The very low levels of caries and the good condition of the teeth even without dental care are remarkable. There are more children with DMFT equal to zero than in similar communities. In the county, there is possibly no racial, genetic or nutritional factor that influences the low prevalence and incidence of caries. There could be an extrinsic factor present in the water acting at a systemic level. It is possible that there is something other than fluoride ions that has the power to prevent caries. |

| Vélez et al. (1970) [15] | Fluoridation technology/Water | To describe the experience with a highly simplified and cost-effective fluoridator, transferable in its present form, or with very feasible modifications, to other rural areas that, from not having this means, would be deprived of fluoridation measures for small water supply systems. | Due to the lack of electrical energy in the municipality of San Pedro, a simple and economical gravity fluoridation system was chosen. The procedure for the installation and operation of the NaF dosing equipment designed by the University of Antioquia are explained, adopting 1 ppm F according to the average annual temperature. | The cost for a community of 4500 inhabitants would be COP 1.33 (USD 0.07) per person per year. The fluoridator described worked with proven accuracy during the four years of the trial. The cost of the accessories and tanks is COP 2420 (USD 138.28). The components of the fluoridator are simple, easy to acquire, economical and safe. This makes it feasible to build and use in any environment. In addition, operation can be performed by an ordinary worker, with easy-to-understand instructions and no risks. |

| Restrepo et al. (1972) [16] | Review/Water, Salt | To investigate the feasibility and effectiveness of adding fluoride to table salt as an alternative caries prevention measure. | In 1963, a census was taken in the four selected communities, in addition to radiographs, clinical and laboratory examinations; dietary survey, determination of average daily salt intake; and caries survey and DMF index. The method for mixing salt and fluoride was studied, considering the optimal concentration of 1 ppm. | The feasibility of adding calcium fluoride or sodium fluoride to salt in a stable mixture was demonstrated. Preliminary results indicate a reduction in caries only in communities receiving fluoridated water and salt. In the future, a study will be conducted on the economic feasibility of the measure for large geographical areas. |

| Rothman et al. (1972) [17] | Dental caries prevalence study/Water | To determine whether children in the municipality of Heliconia really have an unusually low caries prevalence, and if so, to identify the causes. | All schoolchildren between 12 and 17 years old were examined (n = 302; 148 from Heliconia and 154 from Don Matías). Teeth were recorded as erupted or unerupted, permanent or deciduous, present or lost. | Children in Heliconia have notably less caries than those in Don Matías. Both municipalities have similar but lower than optimal fluoride concentration in drinking water. No known factors influencing caries activity could explain the low caries prevalence in Heliconia, although the role of undetermined or undiscovered environmental factors could be important. Factors such as fluoride, oral hygiene, diet, genetics or location do not seem to be the cause of the marked difference in caries prevalence. |

| Vélez et al. (1973) [18] | Nutritional status study/Salt | To correlate the values found for height, weight and bone growth in communities with different socioeconomic levels and with different nutritional intakes. | In the four communities, weight and height were measured in two groups: the first formed by the totality of the schoolchildren (n = 2475) and the second by the population from 0 to 18 years from the control families. Hand and wrist radiographs were taken in the latter group (n = 1513). For control purposes, 366 measurements were taken in schoolchildren from a private school in Medellin. | There is growth and development deficiency in schoolchildren from the four communities in the salt fluoridation study when compared to children from a private school with a high socioeconomic status. Studies on the diet of these communities suggest that the protein and calorie intake is responsible for growth retardation and malnutrition. |

| Glass et al. (1973) [19] | Trace element concentration/Water | To evaluate trace element concentrations in drinking water samples from Don Matías and Heliconia municipalities, and relate the observed differences to the marked difference in the prevalence of dental caries. | A total of 41 samples were taken in the Heliconia houses and 50 in Don Matías. Trace element analyses were conducted by emission spectroscopy. Soluble fluoride levels were also analyzed using an electrode. | A total of 13 trace elements were studied. The concentrations of calcium, magnesium, molybdenum and vanadium were higher in the Heliconia samples, while the concentrations of copper, iron and manganese were higher in Don Matías. None of the samples contained more than 0.3 ppm F. The average fluoride level was less than 0.1 ppm in each municipality. |

| Hernández et al. (1973) [20] | Food survey/Salt | To show the results of the food survey conducted in the two communities receiving fluoride salt within the salt fluoridation study (Armenia and Montebello) and correlate these data with the incidence of dental caries. | The survey was conducted in 7 days with the method of the Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP). The average daily nutrient intake per person and the nutritive value of the average diet by social class and by community were calculated. | There are deficits of the various nutrients in the population evaluated. Most belong to the poor and very poor socioeconomic classes, where nutritional intake is much lower. The consumption of dairy products, eggs, meat and vegetables with high-biological-value proteins is minimal. This deficiency is reflected in the growth and development disorders of individuals. The diet of the communities is based on cereals, sugars, tubers, plantains and a minimal amount of fat. |

| Hernández et al. (1974) [21] | Food survey/Water | To show the results of the food survey conducted in the municipality that receives fluoridated water (San Pedro) and the control, which does not receive fluoride (Don Matías). Then, a comparison, from a nutritional point of view, of communities that receive fluoride salt and establish the possible role of diet in reducing dental caries. | Considering gender and age of the sample, as well as socioeconomic level and family income, the consumption of different food groups and their proportion in the average diet were observed. These data were contrasted with the nutritional recommendations for nutrient intake. | Both communities were found to have a low intake of high-biological-value proteins, a more or less adequate intake of calories and a very low intake of fats, calcium and various vitamins. Most people were poor or very poor, whose nutritional intake is extremely below the recommended levels. The same was observed in Armenia and Montebello. |

| Hernández et al. (1974) [22] | Food survey/Salt | To know the daily salt intake, per person and per day, in the four communities within the study, in order to add fluoride to table salt in a dose capable of preventing caries in a manner equivalent to the amount used in drinking water. | The study was conducted by social class due to the variation in consumption according to economic capacity. The weight of the food was measured during 7 days paying special attention to the salt consumed by the family at the beginning and at the end of the evaluation. | It is necessary to add 1 mg F for every 10 g of table salt to prevent caries. The salt consumption in the 231 families studied ranged from 3 to 30 g. The average salt intake was similar in the four communities. |

| Mejía et al. (1976) [23] | Effectiveness study/Salt | 1. To study the effectiveness of common salt as a carrier of fluoride to prevent dental caries. 2. To compare the relative effectiveness of sodium and calcium fluorides as salt additives in preventing caries. 3. To establish the optimal dose of fluoride in table salt to achieve the maximum level of preventive action without risk of fluorosis. 4. To compare the efficacy of fluorides administered through table salt with those applied in water. | Four communities similar in their socioeconomic conditions, nutritional and health status, geographical location and minimal migration movement were selected. Since 1965, fluoride salt has been administered in two communities: Armenia (calcium fluoride) and Montebello (sodium fluoride); in San Pedro, fluoridated water was distributed and Don Matías was the control community that was left without receiving fluoride. Epidemiological surveys of dental caries were conducted annually from 1964 to 1972, to observe the variations presented. | The results confirm the discovery of a caries prevention method: adding fluoride to table salt. This is a viable method, since it is a food staple, low cost and easy to obtain. Fluoridated salt can prevent caries by 60 to 65%, similar to fluoridated water. A dose of 200 mg F/kg of salt is efficient. |

| Marthaler et al. (1978) [24] | Review/Salt | To expose some studies on salt fluoridation and show the limitations of this method. | Studies from Switzerland, Colombia, Spain and Hungary on salt fluoridation are reported. Difficulties are pointed out, such as: the method of producing fluoridated salt is different in each country; the determination of optimal fluoride levels in salt may vary significantly according to the different means of access to the product and waste in food preparation. It is important that the excretion of fluoride in urine is 1 ppm F. | Fluoride ingested with salt prevents caries. The cariostatic effectiveness of salt appears to be equal to that of water when the fluoride concentration is adjusted to the levels excreted in urine. It is possible to make a stable and homogeneous mixture of salt and fluoride. |

| Herazo-Acuña, B. (1982) [25] | Review/Topical application, self-applications, mouthwashes, salt and water | To promote primary oral health care in as much as possible. | Current status of oral health in Colombia, considerations about dentistry, primary health care activities, water fluoridation and salt fluoridation (if the program were to be implemented, water fluoridation would have to be suppressed as one replaces the other). | Primary health care must be prioritized. The fluoridation of water or salt must be promoted in order to reduce caries by 50 to 60%. The combination of this with other measures will allow Colombia to reach the year 2000 with a 90% reduction in oral pathologies. |

| Herazo-Acuña, B. and Salazar-Oliveros, L. (1983) [26] | Review/Water, salt and topical applications | To show some aspects of preventive programs in Colombia and to highlight the country’s experience in applying preventive measures to avoid oral pathologies. | General history of fluoride use; experience with fluoride use in several cities in the country; salt fluoridation; National Program for fluoridation of water supply systems; preventive dental action (annual topical applications); projects to fluoridate salt in Colombia. | The article looks forward to the results of the research conducted at the moment, in order to establish a national salt fluoridation program in Colombia in the future. |

| Herazo-Acuña, B. (1984) [27] | Review/Topical applications, mouthwashes, water and salt | To condense as much information as possible on fluoride and make it a comprehensive reference material for dentists. | Natural state, procurement, compounds, toxicology of fluoride, clinical symptoms of acute fluoride poisoning, benefits of fluoride, mechanisms of action of fluoride on dental caries and the phases of incorporation of fluoride into the tooth. | In most countries of the world, numerous preventive programs against caries and periodontal diseases have already been carried out, based on fluoride intake and to date no pathology produced or derived from this process has been reported. The known cases of fluorosis are due to the ignorance, in some cities, of the fluoride content in their public supply water and timely defluoridation programs are not carried out. |

| Herazo-Acuña, B. and Salazar-Oliveros, L. (1985) [28] | Study of fluoride sources for use in different vehicles | Communicate to professionals, industry and interested sectors about the great opportunities Colombia has to become a fluoride producer and exporter. | Information from the Colombian Mining Inventory on fluorite (insufficient) and phosphate rock (the largest) is presented. | This study demonstrates the possibility of producing the full range of fluorides in Colombia, being technically feasible and cost-effective. The fluoride plant will produce social, economic and political benefits for a region of Colombia and for the country as a whole, helping to produce jobs. |

| Calle et al. (1990) [29] | Effectiveness study/Water, salt and topical applications | 1. To determine the oral health status of the population under 20 years of age, after 20 years of the policy. 2. To determine if the results influence the coverage of oral health services. 3. To observe the behavior of caries and periodontal disease in order to reorient or modify technical–administrative norms. 4. Compare these results with future results with fluoride in salt. | In 1968, given the precarious oral health in Medellín, an alternative was sought to prevent caries on a collective level. Since 1969, an organized policy was based on prevention programs (water fluoridation, prevention activities and sealants) and assistance. This study coincided with the extinction of water fluoridation and the introduction of salt fluoridation. | It has been possible to control caries and periodontal disease, reducing the DMFT, dento-maxillo-facial anomalies and dental mortality, as well as the need for treatment and increasing the coverage of dental services. The number of people without caries increased. Early caries and periodontal disease control was achieved, meeting and exceeding the WHO and World Dental Federation (FDI) goals for the year 2000, so bolder goals were set for Medellin in the future. |

| Title | Date | Institution | Vehicle | Topic | Orientation/Recommendation/Declaration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution 2772 of March 27, 1978 [31] | 1978 | Ministry of Health | Salt | Creates the Committee for feasibility studies for the fluoridation of salt in Colombia. | Conduct studies and research necessary to decide whether to fluoridate salt in Colombia. |

| Law 9 of January 24, 1979 [32] | 1979 | Colombian Congress/Ministry of Health | Water | It dictates sanitary measures. | Art. 73. The Ministry of Health is responsible for the approval of the programs of fluoridation of water for human consumption, as well as of the compounds used to carry it out, its transportation, handling, storage and application of the methods for the disposal of residues. |

| Decree 2105 of July 26, 1983 [33] | 1983 | Ministry of Health | Water | Partially regulates Title II of Law 9 of 1979 regarding water potabilization. | Art 17. The content of fluoride as fluoride ion, F- should be controlled according to the average temperature of the environment. |

| Decree 1594 of June 26, 1984 [34] | 1984 | Ministry of Agriculture/Ministry of Health/National Planning Department | Water | Partially regulates Title I of Law 9 of 1979 regarding water uses. | Admissible quality criteria for the agricultural use of the resource: fluoride in quantities of 1 mg/L. The specific electrode, SPADNS and alizarin methods of analysis for fluoride are considered officially accepted. |

| Decree 2024 of August 21, 1984 [35] | 1984 | Ministry of Health/ Ministry of Economic Development | Salt | Determines the standards on iodization and fluoridation of salt for human consumption and regulates the control of its repackaging. | The fluoride content in salt must be in the proportion from 180 to 220 ppm. Salt packaging and containers must comply, among others, with the labeling requirements: fluoride and iodine content expressed in ppm. |

| Author–Year | Study Design/Vehicle | Aim | Methods/Development | Results/Final Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freire, P.S. (1964) [36] | Fluoride use in school programs/Water, topical application of sodium fluoride solution | Describe the incremental dental care program applied, combining curative and preventive services, which was approved as the standard for other communities in Brazil. | In Aimorés MG, two prevention methods were used: fluoridated water and topical application of 2% sodium fluoride. The plan had two phases: the initial program and the maintenance program. | After 5 years of operation, there were no accumulated dental needs and a significant increase in caries-free teeth. |

| Mello, C.F. (1966) [37] | Review/Water, topical application of sodium fluoride solution | Study the caries preventive and control measures that can be put into practice by dentists in their daily routine, in health care services and in private practices in Brazil. | It brings together much of what was known about caries and its prevention up to that point. The topics covered are caries basics, diet, microorganisms, fluoride, education and caries control. Regarding fluoride, the presence of fluoride in human and animal teeth and bones, stained teeth and caries prevention are described. | Water fluoridation can only be applied in communities that have a water treatment system and whose authorities are willing to support the measure; there are many communities that do not have such conditions. There is an urgent need to tackle the problem of caries with other preventive methods. Preventive measures should be put in place with the help of federal or local programs, such as health education, hygiene, fluoride tablets or topical applications. |

| Viegas, Y. (1970) [38] | Effectiveness study/Topical application of acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF) solution | Assess whether APF solutions, which have a proven effect on children, also have an effect on young adults, who already have mature enamel. | The study comprised a topical application of APF solution, containing 1.23% fluoride, to 75 undergraduate students with an average age of 20 years, themselves serving as controls. | There was a 27.66% reduction in the incidence of caries. The results allow the application of APF solution to young adults to be recommended. It would be desirable that this study be repeated in order to confirm the results obtained. |

| Viegas, Y. and Viegas, A.R. (1974) [39] | Effectiveness study/Water | Present and analyze the data on dental caries prevalence verified in the study of public water supply fluoridation in Campinas. To verify the dental caries reductions found in permanent and primary teeth during the ten-year period of water fluoridation. | Children from 4 to 14 years old were included in all four surveys. In the last three surveys, only children who have always lived in Campinas were examined. The indices used were DMFT, dmf and that of permanent first molars. | The caries prevalence reductions observed were 66% for permanent teeth and 53% for primary teeth. In children aged 6 to 10 years, 25% have no decayed primary teeth and 36% are in the same condition for permanent teeth. |

| Horowitz et al. (1974) [40] | Fluoride use in school programs/Topical self-application of APF solution and gel | Evaluate the effect of self-applications of APF in solution and gel, through supervised brushing. | A total of 566 children between 14 and 17 years old in São Paulo participated. Five study groups were formed: A (control) brushed their teeth with a fluoride-free prophylactic paste and then with a placebo solution; B brushed their teeth with the paste and then with APF solution (0.6%); C brushed their teeth with the same APF solution without brushing first with the paste; D brushed their teeth with the paste and then with APF gel (1.23%); and E brushed with the same APF gel without brushing first with the paste. Fifteen brushings were supervised at the school over 3 years. | There are a number of important non-controllable variables in the program: the actual conduct of the brushing sessions, exposure of the study population to fluoride (although some fluoride toothpastes are sold in Brazil, none of the compositions are similar to those accepted by the ADA or tested for efficacy), and the degree of oral care. After the 3 years of the study, there were incremental reductions in DMFS of 26, 26, 33 and 19% in groups B, C, D and E, respectively, compared to the control. Equal or even greater benefits were seen when fluoride was administered weekly or biweekly via mouthwashes. Whether the benefits are from supervised brushing or educational action remains to be seen. |

| Grinplastch, B.S. (1974) [41] | Review/Water | Recommend water fluoridation, which is one of the great advances in modern public health. Focuses on the compound fluorite or calcium fluoride. | Mentions the abundance of fluorite in Brazil, but the difficulty in using it because it is not water soluble. Reports the attempts and studies conducted to enable the use of fluorite in water fluoridation. | The incidence of caries can be reduced by about 65% by using water with fluoride content around 1 mg/L. Water fluoridation does not change any of the properties of water and is recommended by international health authorities as the only effective measure to prevent dental caries. The installation of fluoride compound factories is suggested. |

| Ando et al. (1975) [42] | Adverse effects of fluoride/Water | Describe dental fluorosis to estimate its severity in schoolchildren aged 6 to 14 years and make some considerations about the various forms of dental condition. | There were 175 schoolchildren, aged 6 to 14 years, all residents of a restricted area of Cosmópolis, SP. The water in this area comes from a semi-artesian well, opened in 1962, and contains about 9.5 to 11 ppm F. The average maximum temperature is 35.5°. The Dean fluorosis index was employed. | All degrees of fluorosis were present, but the moderate form was the most prevalent; there was no marked difference between the mean dental fluorosis rates in schoolchildren who ingested water soon after birth and those who started years later. |

| Saliba et al. (1975) [43] | Monitoring/Water | Check the differences that may exist in the determination of the concentration values of the fluoride ions existing in public supply waters; if differences exist, check if they have any positive or negative trend; and the importance of this trend. | A total of 32 water samples from public water supply systems with treatment plants or served by wells were evaluated. Given the existence of interferents that can induce errors in the determination of fluoride, a preliminary determination was made, then distillation of the samples and the final determination by 3 processes: Colorimetric methods SPADNS (Hach DR-El-AC) and Scott–Sanchis (HelligeAquatester and Nessler tubes). | The samples were within the recommended limits (0.6 to 1.5 ppm F). The fluoride ion determinations by the two methods differ from each other with a positive trend, since the Hach DR-EL-AC device shows higher results most of the time. For the most unfavorable case, which is that the difference of 0.11 mg/L always occurs, this does not cause any problem for the population’s health, and the additional costs are small, allowing both medium and small cities to control the fluoride concentrations in their water supply systems without major problems. |

| Ando T. (1975) [44] | Effectiveness study/Water | 1. Study the caries prevalence in permanent teeth in schoolchildren residing in two regions with high and low fluoride content in the water. 2. To verify the possible difference regarding sex in caries prevalence in schoolchildren in the two areas. 3. Try to establish a relationship between the role played by fluoride, under fluorosis condition in reducing the caries prevalence in schoolchildren living in the area whose water supply has a high fluoride content. | We examined 324 schoolchildren from 7 to 14 years of age of both sexes. The sample was divided into 2 groups. The fluorosis group (n = 164) from the area with a high fluoride content (9.5 to 11 ppm) and the control group (n = 160) from the urban area, where the water supply contains about 0.05 ppm F. The mean DMFS index and clinical and radiographic examinations were used. | The caries prevalence observed in the fluorosis group was lower when compared to the control group. In both groups, there was no statistically significant difference between sexes in caries prevalence. The mean DMFS increased over time in both sexes and in both groups. Under dental fluorosis conditions, teeth were protected against caries both in those that calcified under this condition and in those that were influenced by an excess of fluoride after mineralization. |

| Freire, A.S. (1976) [45] | Effectiveness study/Water | Present the first results obtained with water fluoridation in Cachoeiro de Itapemirim, ES, after 6 years of implementation of the measure. | After an economic feasibility study, the Autonomous Service of Water and Sewage (SAAE) acquired the equipment to implement water fluoridation. The daily control is conducted by the Scott–Sanchis method. To date, fluoridation has not been interrupted and presents an average daily content of 0.8 ppm F. | In 1975, six years after the installation of water fluoridation in 1969, a notable reduction in caries rates is observed, despite not having alarming rates before fluoridation, due to the fact that there was reasonable school dental care. |

| Saliba, N.A. and Saliba, O. (1977) [46] | Effectiveness study/Topical application of APF solution | Compare methodologies employed by two researchers who obtained contradictory results on topical fluoride application. | The study started with 142 schoolchildren aged 7 to 10 years, of both sexes, and ended with 92. An acidulated fluoride solution (1.23% fluoride in orthophosphoric acid) was used after general prophylaxis. | The analysis of the results obtained revealed that topical application reduced caries incidence by approximately 16% with both one and two topical applications. |

| Rocca et al. (1979) [47] | Effectiveness study/Water | Compare the data collected on caries prevalence in Araraquara and in Guariba, SP, where the water is fluoride-free. | The sample was 860 schoolchildren from 7 to 12 years of age, of both sexes. The DMFT and DMFS indices were used. | Schoolchildren from Araraquara, where the water is fluoridated, had lower rates of DMFT, DMFS and loss of first permanent molars than those from Guariba. |

| Alcaide and Veronezi. (1979) [48] | Adverse effects of fluoride/Water | To investigate the presence of dental fluorosis in the city of Icém, measuring its extent, providing subsidies, and sensitizing the authorities directly related to the problem, aiming to solve it. | The sample was 449 children from 7 to 14 years born and always residing in Icém. The indices of Dean and Arnold, DMF and dmf were used. The physical-chemical tests revealed that one of the wells contained 4 mg F/l and the other 2.6 mg F/l, where it should contain 0.7 mg F/l. | Only 11.8% of the children were free of fluorosis, with few questionable (3.5%) and severe (0.06%) cases. There is a predominance of very mild degree (45.6%) and balance between mild and moderate degrees (18.9% and 19.3%, respectively). Children aged 9 to 11 years have the highest prevalence of dental fluorosis. The mean DMF was 2.60, classified as low. |

| Diniz and Cardoso (1979) [49] | Effectiveness study/Water | Compare the results of fluoridation of public water supplies between the cities of Juazeiro (BA) and Petrolina (PE), using calcium fluoride (fluorite). | A total of 1350 schoolchildren from 6 to 14 years old from Juazeiro and 900 from Petrolina were examined. Children born and resident since the time fluoridation started (1970) were included. The cost of fluoridation was calculated. | The percentage of caries-free schoolchildren in Juazeiro is higher than that of Petrolina (whose fluoridation was interrupted), and had an average reduction of 34.73%. The per-capita cost for Juazeiro was very low for the great benefit it provides. |

| Guimarães et al. (1980) [50] | Effectiveness study/Water, topical application of APF | Evaluate the reduction in caries incidence by the association of two preventive methods (annual topical application of acidulated sodium fluoride associated with fluoridation of public water supplies). | The sample of 177 schoolchildren aged 7 and 8 years, of both sexes, living and studying in areas with fluoridated water, and residing in Piracicaba since birth, was divided into 2 groups: control (did not receive topical fluoride application) and experimental (received an annual application for 2 consecutive years). The DMFT index was collected at the beginning and at the end of the study. | The annual topical application of acidulated sodium fluoride for 4 min, preceded by the cleaning, isolation and drying of teeth, associated with the fluoridation of public water supplies, is efficient in reducing caries incidence. In permanent teeth, there was a 22.7% reduction. The best orientation is to take preventive topical application programs to areas where there is no water fluoridation. |

| Cury et al. (1981) [51] | Monitoring/Toothpaste | Determine the concentration and analyze the forms of fluoride found in toothpastes sold in Brazil to assess the potential for preventing dental caries. | The fluoride content in the toothpastes Anticárie Xavier, Signal F, Kolynos SMF, Kolynos Gel F, Fluorgard and Pruf, purchased in the local market in Piracicaba, was potentiometrically analyzed. The manufacturing date is not indicated. The forms of fluoride were identified: free ionic fluoride (active in caries prevention), phosphate-bound fluoride MFP (active in caries prevention) and insoluble fluoride (bound to the abrasive and inactive in caries prevention). | The MFP concentration ranged from 657 to 902.3 ppm. The percentage of total fluoride ranged from 65 to 96%. Most of the dentifrices have a total fluoride concentration close to that indicated by the manufacturer. All the analyzed toothpastes commercialized in Brazil have a MFP concentration sufficient to prevent caries. However, as MFP breaks down over time, it is necessary to prove the stability of the dentifrice so that the prevention potential is preserved. |

| Moitta, F. (1981) [52] | Review/Water | Show the status of water fluoridation in Brazil from the beginning in 1953 to the present. | More than 30 cities (20 million people) have benefited. There is mention of the fluoride compounds used and the contribution of FSESP, the Ministry of Health and the National Institute of Food and Nutrition (INAN). The research of new fluoridation methods and the national production of fluorosilicic acid were encouraged. | A little more than 10% of Brazil’s population benefits from the measure. To reduce caries, the measure must be intensified and extended to populations in need. The Federal and State Governments should become aware of the socioeconomic importance of the measure and promote it, ensuring support and resources. |

| Araújo, IC. (1982) [53] | Fluoride use in school programs/Mouthwashes, topical application of sodium fluoride | Plan and implement the dental health policy through incremental treatment, reaching, in a staggered and compulsory way, schoolchildren from 6 to 14 years old. | The focus was children from 6 to 14 years of age, from the schools where the project will be implemented gradually. The maintenance service will be the responsibility of the neighborhood Health Unit. | The activities planned by the Health Secretary are guided by norms and instructions, taking into account the following aspects: hierarchization of the dental problem; establishment of priority criteria; standardization of equipment and supplies; service supervision; statistical data collection; production and productivity evaluation, and development of oral health educational actions. |

| Diniz et al. (1982) [54] | Economic aspects/Water | Research a simple and economical process of fluoridation of water supplies for small communities through the use of fluorite. | Technical and scientific criteria of a simplified water fluoridation technique developed for small communities are presented. Calcium fluoride (fluorite) was used as basic material, following the natural content of fluoride in water. | This technique assumes low cost, ease of operation, and use of locally available natural resources. |

| Vasconcellos, M. C. C. (1982) [55] | Effectiveness study/Water | Verify the caries prevalence and the level of dental care with respect to the disease in the urban school population of Araraquara. | The sample was 9923 schoolchildren from 7 to 12 years. The examinations were conducted in November 1979 and the DMFT index was used. | The DMFT index values are higher than those expected for a community whose public water supply has been fluoridated for approximately 16 years. The data strengthen the hypothesis of discontinuity in the concentration of fluoride in water. |

| Pinto, V. G. (1982) [56] | Review/Salt | To discuss the feasibility of using table salt as a carrier for fluoride in caries prevention in Brazil. | It considers several points such as the Colombian study, the Brazilian position favoring water fluoridation, salt iodation and individual variations in salt intake. | In view of the current scientific knowledge and the peculiarities of Brazil, the widespread adoption of fluoridated salt for caries prevention is not justified. The use of fluoridated salt is valid only in restricted areas and under technical control. Water fluoridation is the method of choice for the country, which should strive for its maximum expansion. |

| Buendia, O.C. (1983) [57] | Fluoride use in school programs/Water | 1. Verify the ideal fluoride content for maximum benefit in reducing caries in schoolchildren. 2. Verify the possibility of appearance of dental fluorosis, due to the ingestion of higher doses of fluoride. 3. Evaluate the strength of the method in reducing caries incidence. | Four studies were analyzed, conducted with fluoridation of school water in four cities with different annual average temperatures and varying the fluoride concentration applied. The results after 6, 8 and 12 years are presented. | The recommended content to fluoridate school water is 4.5 times higher than that indicated in municipal water. The reduction in caries incidence in children ranges from 34.9 to 39.7% with 8 years of implementation. Water fluoridation in schools is a safe and effective method. |

| Pinto, V.G. (1983) [58] | Review/Water, mouthwash, topical application | Understand the current situation in the country in terms of the dental situation as a whole, by gathering data and indicators, directly or indirectly related to dental health, and critically analyzing them. | It provides a Brazilian dental health panorama, with emphasis on the economic and epidemiological situation, caries prevention, human resources, financial expenditures and services delivery structure. | It suggests guidelines to manage the Dentistry Program. Foresees the changes and criteria that a new dental policy for Brazil should include throughout this decade. It is expected that, by the year 2000, about 85% of the urban population have treated water and half with fluoride. |

| Buendia, O.C. (1984) [59] | Effectiveness study/Mouthwash | Comment on the advantages of using fluoride mouthwashes in the prevention of dental caries. | A sodium fluoride solution was applied with a weekly technique employed in 494 municipalities in SP, having benefited 1,665,364 students until December 1982. | Fluoride mouthwashes use is an alternative solution for people living in places without fluoridated water, for being a simple and easy method to be applied. With 2 years of usage, the average caries reduction was 35%. |

| Viegas and Viegas (1985) [60] | Effectiveness study/Water | Verify the reductions in dental caries in primary and permanent teeth during 10 years of fluoridation of public water supplies. | Children from 3 to 14 years old and young adults from 15 to 19 years old who have always lived in the city of Barretos, SP, were examined. Evaluating decayed, filled, lost, healthy teeth, caries in the lower right permanent first molar and upper central incisors. | There was a reduction in the mean DMF at all ages. In the group of 3 to 5 years, 52% are caries free. In the group of 6 to 14 years, the percentage of healthy and restored teeth increased, and the percentage of decayed and extracted teeth decreased. In the 6 to 10 age group, there was a 55% reduction in caries. In the 15 to 19 age group, there was a 100% reduction in the need for dentures. |

| Lacerda, J. L. S. (1985) [61] | Effectiveness study/Water | Ratify the importance of fluoride therapy for caries prevention through water fluoridation with fluorite in Minas Gerais. | The data collected by the epidemiological dental caries surveys were compared using the DMF index before and after fluoride. | In some cities, there was a caries reduction of between 64 and 73%. There was a decrease in the average number of decayed permanent teeth and an increase in restored permanent teeth. There was a high percentage of children with zero caries (33 to 39%). |

| Bastos et al. (1985) [62] | Adverse effects of fluoride/Supplement | Analyze fluoride intake during the calcification phase of teeth, discussing fluorosis and prescribing the amount to be administered daily for pregnant women and children. | The recommended dosage for pregnant women and children according to some authors and according to the ADA is 0.50 mg F/day. Fluorosis will only develop with the average ingestion of 2 ppm or more, and the risk only exists if it is consumed systemically. | A dosage of 0.50 mg F/day is recommended for children up to 3 years old, and 1 mg F/day for children older than 3 years. For pregnant women, the recommended dosage is 1 mg F/day. Given the very high caries prevalence in Brazil, fluoride supplements can and should be prescribed by a doctor or dentist in regions without fluoridated water. |

| Viegas and Viegas (1985) [63] | Effectiveness study/Water | Present and analyze the prevalence data of dental caries verified in the study of water fluoridation in Campinas. | The prevalence data of caries in schoolchildren aged 4 to 14 years were analyzed to verify the reductions in caries during 14 years of water fluoridation. The methodology and technique were the same used in the 4 previous surveys (1965, 1969, 1972 and 1976). | The reductions in caries prevalence were 57% in permanent teeth and 49% in primary teeth. In children aged 4 to 14 years, 26% have no decayed teeth, and in children aged 5 to 14, 29% are in the same condition as for permanent teeth. |

| Martins et al. (1985) [64] | Effectiveness study/Water | Analyze clinically, radiographically and statistically the caries prevalence in deciduous teeth in Belo Horizonte MG, whose public water supply has the ideal fluoride concentration, and in Rio Acima, MG, whose water does not contain fluoride. | The sample consisted of 742 schoolchildren aged 7 to 10 years, of both sexes, of low socioeconomic level, without distinction of color. There were 450 from Belo Horizonte (0.76 ppm F) and 292 from Rio Acima (0.10 ppm F). Water samples were collected in both cities. The dmfs index was used. | The caries prevalence in deciduous teeth is higher in Rio Acima children than in Belo Horizonte children. There was a 33.18% caries reduction in deciduous teeth in children who always used water with the ideal fluoride concentration. |

| Bastos, J.R.M. (19859 [65] | Effectiveness study/Supplement | Show the use of fluoride supplementation as an alternative method of caries prevention. | In a country with the highest caries rate in the world, it is important to indicate fluoride for pregnant women and children, trying to reduce caries in the population as much as possible. | In a non-fluoridated area or with low F concentration (1.5 to 2 mg F/day), supplements should be prescribed. In areas with unsatisfactory fluoride levels, the supplement can potentiate the effect of fluoride. |

| De Pretto et al. (1985) [66] | Effectiveness study/Water | Present the results after 8 years of fluoridation and describe current techniques for fluoride use in semi-artesian wells in Bauru, SP. | The processes and costs of fluoridation in the benefited regions are explained. A dental caries survey was conducted in 1984 on 2416 students from 8 elementary schools located in area with fluoridated water, after 8 years of water fluoridation. Another survey was carried out in 1976 (1515 schoolchildren). The DMFT index was used only for permanent teeth. | The number of teeth attacked by caries was lower in 1984. The reduction ranged from 29 to 36% according to age. The possible causes of this difference are children living in areas without fluoridated water, the habit of families to use water from artesian wells even with the availability of fluoridated water and interruptions of fluoridation until 1981. It is recommended to extend the fluoridation system to the entire city and to extend an educational campaign for parents to understand the importance of water quality and fluoridation. It is safe and no harmful effects have been noted at 0.9 ppm. |

| Cury, J.A. (1986) [67] | Monitoring/Toothpaste | Study the stability of fluoride in dentifrices sold in Brazil in terms of caries prevention potential. | Seven toothpastes were analyzed at the time of purchase and after 6 and 12 months of storage in their original packaging and at room temperature. The fluoride content and its different chemical forms (free ionic fluoride, MFP and insoluble fluoride) were determined. | In fluoride-containing toothpastes, its concentration decreased, increasing the percentage of fluoride bound to the abrasive. In MFP-based toothpastes, it remained stable or underwent hydrolysis, increasing the concentrations of fluoride bound to the abrasive. In some toothpastes, this instability may compromise their cariostatic effect. |

| Teixeira, R.N and Cury, J.A. (1986) [68] | Monitoring/Toothpaste | Test the reactivity of the fluoride present in toothpastes sold in Brazil, providing a comparative and complementary analysis. | Toothpastes purchased in the local commerce of Piracicaba, SP, were evaluated in vitro. The concentrations of total fluoride, calcium fluoride and fluoridated apatite were determined in the enamel after reactions with the toothpaste solutions. | Toothpastes have been shown to be highly efficient in their ability to form calcium fluoride in the enamel. Given the importance of toothpastes in the decline in caries prevalence in industrialized countries, it is up to dentistry to demand quality control from the factories and the government, so that the same can occur in Brazil. |

| Vertuan, V. (1986) [69] | Effectiveness study/Water | Compare the mean caries index before fluoridation and 19 years after fluoridation started. | Sample of 639 schoolchildren aged 7 to 12 years from 9 schools. All drank fluoridated water since birth and always lived in Araraquara SP. The DMF index was used. | There was a 41.8% reduction in caries incidence after 19 years of water fluoridation, although a better result was expected. Compared to the data from 1972, there was an increase in the caries rate in the group studied. There is a need for greater concern and priority to maintain optimal standards of fluoride in water to achieve better oral health. |

| Zamorano et al. (1987) [70] | Effectiveness study/Water | Compare the prevalence of caries in permanent teeth in Belo Horizonte (0.76 ppm F) and Rio Acima (0.10 ppm F). | Sample of 946 schoolchildren (567 from Belo Horizonte and 379 from Rio Acima) of both sexes, between 7 and 11 years, of low socioeconomic level, without distinction of race, who were born, had always resided and consumed water from public supplies in the two cities. Clinical and radiographic exams were performed. | Caries had an average reduction of 51.64% in both cities. The difference between the means of the DMFS index is lower in Belo Horizonte. Caries is a progressive and cumulative disease. |

| Viegas et al. (1987) [71] | Advocacy/Water | It is a document in response to an narrative that TV Globo presented about the fluoridation of public supply water in March 29, 1987. | There were 3 questions asked in the program:

| There is no scientific basis for the criticisms that were made about water fluoridation in the TV show. It is necessary to stress that this method has been exhaustively studied and is approved by the international scientific community and should be an integral part of the National Health Policy, as a condition to have better Dental Health for the population of Brazil. |

| Nobre dos Santos and Cury (1988) [72] | Effects of cessation/Water | Report the alteration of fluoride concentration in plaque after discontinuation of water fluoridation in Piracicaba, SP, Brazil. | The water was fluoridated in 1971. Fluoridation was discontinued in 1987 due to a shortage of sodium fluorosilicate. Dental plaque was collected from 91 children of both sexes, 6 to 8 years of age, during the last 6 months of water fluoridation (0.8 ppm F) and from 41 children after its cessation (0.06 ppm F). | The fluoride concentration in the plaque 2 months after stopping water fluoridation was lower than during fluoridation. Discontinuation of water fluoridation may contribute to the reduction in the cariostatic effect due to the interruption in fluoride intake. |

| Cury, J.A. (1988) [73] | Monitoring/Toothpaste | Evaluate the fluoride of two dentifrices that offer chemical control of dental plaque. | Toothpastes of the brands Colgate Antiplaca and Prevent were evaluated. A non-fluoride dentifrice was used as a control. The reactivity of fluoride in the toothpastes with human tooth enamel was verified by assessing the total fluoride ion concentrations (TF), in the form of calcium fluoride and in the enamel after the reaction with the toothpastes simulating brushing. | In the event of failure of the dentifrices in the mechanochemical control of dental plaque, the efficiency in caries prevention will be better ensured by the Prevent dentifrice, which has fully available, stable and more reactive fluoride than Colgate Antiplaque. |

| Viegas and Viegas (1988) [74] | Effectiveness study/Water | Verify dental caries reductions found during the sixteen-year period of public water supply fluoridation. | The results of the prevalence data of dental caries in children aged 5 to 14 years and adults aged 15 to 24 years from the city of Barretos, SP, Brazil, were analyzed. | In the 5- and 6-year-old children, 66.1% had no decayed teeth; in the 6- to 14-year-olds, there was a 54% reduction in the average DMF; and in the 12-year-olds, the average DMF was 3.5. In the 18-year-olds, 72.3% had all their teeth, and in the 15- to 24-year-olds, there was a 90.25% reduction in the need for dentures. |

| Lopes et al. (1988) [75] | Effectiveness study/Water | Compare the prevalence of caries in permanent first molars of children who were born and have always resided in two communities in the state of Piaui (one with fluoridated water and the other without). | The DMFS index of the first permanent molars was used. These teeth were examined clinically and radiographically in a sample of 360 schoolchildren aged 7 to 12 years, of both sexes, of low socioeconomic status, without distinction of race, who were born and had always resided in the cities of Teresina and Barras, PI, the first, with fluoride in the public water supply (0.68 ppm F) and the second without fluoride. | For all ages and sexes, in children in the city without fluoride, prevalence rates were always higher. The percentage reduction at all ages, in both sexes and in both communities was between 19.38% and 38.09%. This may be explained by an under-fluoridation reported in 1985–1986 in the public water supply of Teresina (0.58 ppm and 0.57 ppm). The DMFS index of Barras was higher when compared to Teresina. |

| Arcieri et al. (1988) [76] | Effectiveness study/Gel, mouthwash | Evaluate the reduction in the incidence of caries through the association of two preventive methods. | A total of 246 students of both sexes, aged 7 to 11 years, from Uberlândia, were examined. They were divided into 2 groups: Group I received half-yearly topical applications of 1.23% APF; and Group II, in addition to the half-yearly topical applications, received weekly mouthwashes with 0.2% sodium fluoride aqueous solution. | After 2 years, group II had a 33.97% reduction in the incidence of caries in permanent teeth. Weekly mouthwashes associated with two annual topical applications of fluoride are effective in reducing the incidence of caries in schoolchildren aged 7 to 11 years. |

| Neder and Manfredini (1991) [77] | Review/Salt | Discuss the sudden launch of the National Program for Caries Control by the Salt Fluoridation Method in Brazil. | The authors considered the Health Minister’s announcement to be irresponsible, 30 years after the implementation of water fluoridation. It would imply importing potassium fluoride from a single producer in Germany and equipment for homogenization; solving operational problems such as correct addition and adequate quality control; differentiated distribution respecting the areas with natural or artificial fluoride in the water; making necessary previous studies such as the food survey evaluating salt consumption in the country by region and social class, the cost not as low as expected and the organization of sanitary control in distribution. | Any decision to change the method of fluoridation used in the country should be subject to prior discussion between public institutions and the citizens involved, as well as the National Congress, which is responsible for making decisions on the use of fluoride as a caries prevention measure in the country. |

| Silva, M.F.A. (1991) [78] | Review/Salt | Analyze the conditions of fluoride use in salt, discussing whether there are conditions for using this method in Brazil. | Its effectiveness is similar to that of water fluoridation and has a very low cost; however, it has technical and dosage control problems. There are problems with the dosage of iodine in salt, observing variations of 30%. If this happened with fluoride, the effect of caries prevention would not be observed or could cause fluorosis. This could make the program unviable and could even cause harm to the supervision of programs such as water fluoridation. There are other problems such as the analysis of the natural fluoride content in salt, the interference of impurities in the salt that may react with fluoride and the control of humidity and flow. | Fluoridated salt is a cheap and effective method for caries control. However, only 27% of the salt produced in Brazil is refined, so a large part of the population consumes unrefined salt. Because of the large number of companies producing salt, it is difficult to control the product at a national level. Companies are not interested in responsible associations with health programs. The observed variation in iodine concentration in salt apparently has no side effects, which would not occur with fluoride. There is a lack of studies on salt intake per capita by region regarding the conditions under which salt is supplied to populations (humidity, packaging, etc.). It would be imprudent to replace a method widely accepted by the population and widely tested nationally and internationally, for one that needs studies due to the peculiar conditions of distribution and consumption of salt in Brazil. |

| Title | Date | Institution | Vehicle | Topic | Orientation/Recommendation/Declaration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinance 33 of 28 May 1968 [79] | 1968 | National Health Department/Ministry of Health/National System of Dentistry Fiscalization | Water | Promotes a study to formulate an Executive Plan for Fluoridation of Supply Water. | Set up study committees composed of three dental surgeons to be appointed by this service. | |

| Law 6050 of 24 May 1974 [80] | 1974 | National Congress | Water | Disposes about the fluoridation of water in supply systems when there is a treatment plant. | Projects for the construction or expansion of public water supply systems, where there is a treatment plant, must include forecasts and plans for water fluoridation. | |

| Decree 76,872 of 22 December 1975 [81] | 1975 | Presidency of the Republic, Civil House, Deputy Chief of Staff for Legal Affairs | Water | Regulates Law 6050 of 1974, which provides for the fluoridation of water in public supply systems. | Projects for the construction or expansion of public water supply systems must contain studies on the need for fluoridation of water for human consumption. Even in systems that do not have a treatment plant, where appropriate fluoridation methods and processes must be used. | |

| Ordinance 635 of 26 December 1975 [82] | 1975 | State Minister of Health | Water | Approves norms and standards on water fluoridation, in view of Law 6050 of 1974. | It details the minimum requirements: continuous water supply, the potability standards, adequate operation and maintenance systems, and routine control of water quality. | |

| Decree 90,892 of 1 February 1985 [83] | 1985 | Presidency of the Republic. Government of the Argentine Republic, the United Mexican States and the Federative Republic of Brazil | Gel | Provides for the execution of trade agreement No. 26 (Brazil’s agreement with Argentina and Mexico), signed in the industry sector of hospital, medical, dental, veterinary and related articles and devices. | On imports of the specified products originating in Argentina, Mexico and Bolivia, Ecuador and Paraguay. Chapter I of the agreement is on industrial sector products, including sodium fluoride gel (caries preventive). | |

| Law 7486 of 6 June 1986 [84] | 1986 | Presidency of the Republic. | Water | Approves the guidelines of the first National Development Plan (PND) of the New Republic, for the period from 1986 to 1989. | Enhancement of the mass prevention program of fluoride in public water supplies. | |