Could Failures in Peer to Peer Accommodation Be a Threat to Public Health and Safety? An Analysis of Users Experiences after the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Assessment of Health and Safety on Peer to Peer Accommodation before the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.2. Assessment of Health and Safety on Peer to Peer Accommodation after the COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

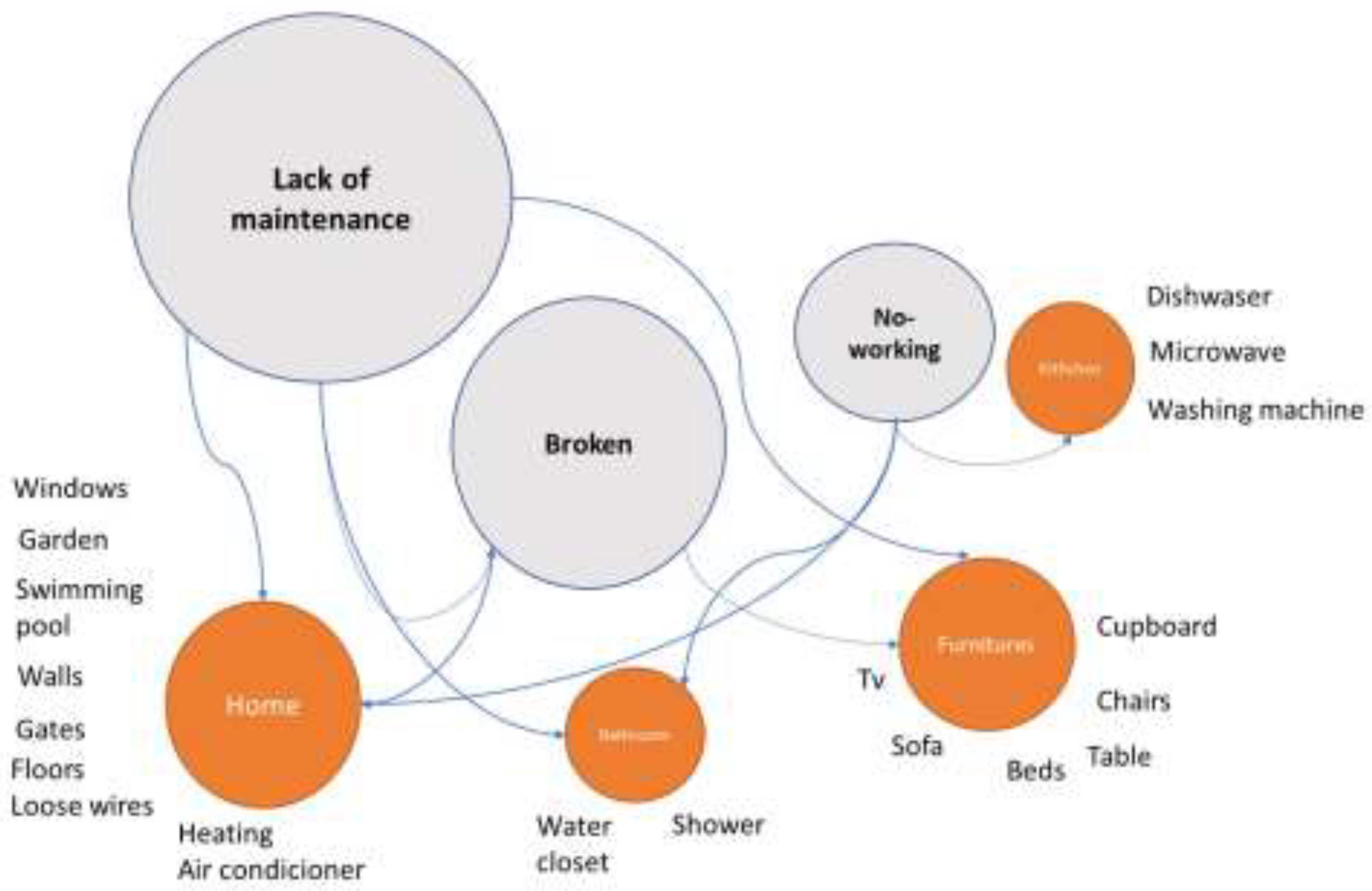

“When I used the washer, the hose did not drain and it was loose and flooded the entire apartment. Every time it rained there were multiple leaks around the unit.”

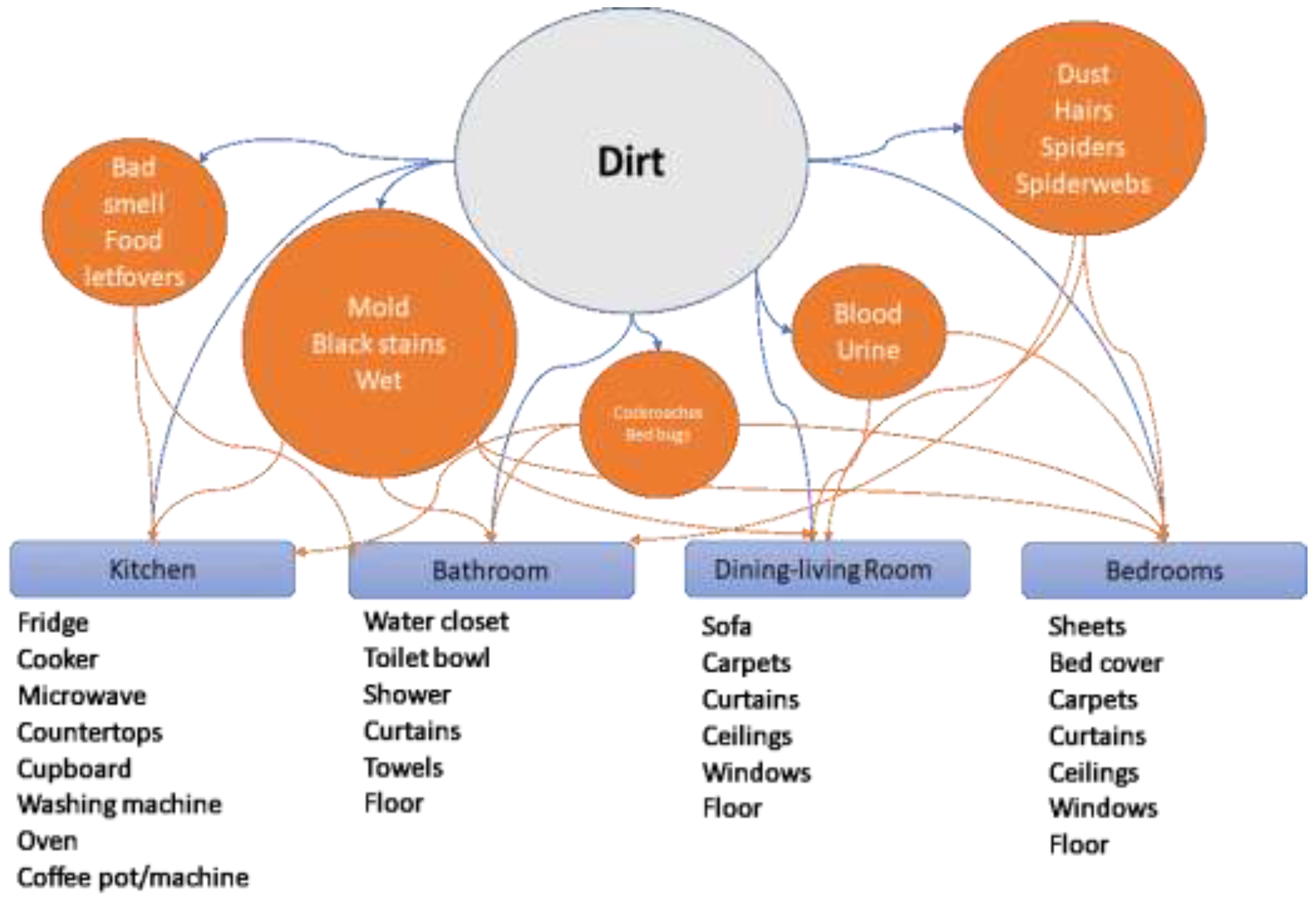

“There was (…) mold on the carpet.”

“We immediately noticed black mold covering the entire HVAC system and surrounding closet within the interior of the property.”

“The place was very dirty, having paw marks in the dust under the bed along with random socks and other trash, and even a black hand mark on the mattress.”

“All over the apartment were spiderwebs.”

“There were old bars of soap in the tub area, splatters in the toilet as if someone just had diarrhea, toothpaste on the mirror and hair on the floor.”

“The bathroom was disgusting with a moldy shower curtain and orange slick grime.”

“It smelled like a medieval pub.”

“The countertops had old food debris and needed to be wiped.”

“Exploded food left by others in the microwave.”

“It was a dump: filthy walls, cobwebs, cupboards falling off the hinges, rusted out washer and dryer, broken dishwasher not attached to the cupboard, all three showers broken, filthy stained couches, soiled mattress with what looked like urine and blood stains, patio furniture covered with blankets to hide the stains.”

“There was blood on the fireplace glass, mold on the carpet, open containers in the refrigerator, urine on the bed hidden with a sheet, who knows what in the shower, and these were just a few things.”

“The snow began to melt and when it did there was about 20 piles of dog feces all over the deck, becoming unsanitary.”

“The place was infested with cockroaches.”

“There were multiple live cockroaches.”

“It was the final straw when I went to brush my teeth at 7:00 a.m. and a cockroach and four baby cockroaches came out of the drain in the sink.”

“I contacted Airbnb about this bedbug problem on March 2. It is currently March 11 and I am sitting in a hotel, still with no answer about this problem.”

“Being bit[ten] by fleas or bedbugs as soon as we lay on top of the bed.”

“My sister got a zip lock bag and put the live bedbug in it.”

“It was disgusting and a health hazard.”

“It was definitely not COVID compliant.”

“The garden area was untidy, with the grass not cut and loose tiles on the path.”

“There are broken or dirty items (linens with blood stains and a foam mattress.”

“The dishwasher was rusty with broken parts; the rust stayed on the presumably washed dishes afterward.”

“The place was hot, like 100 degrees F hot (+30 Celsius), and all three bedrooms did not have AC. There were two ancient AC units in the living room and dining room.”

“We could see the door lock on the security gate wasn’t installed and there was a gap.”

“The floor was chipped and cracked and the window screen was broken.”

“The stained mattress was still in place, and there was a broken dishwasher and cupboards.”

“Broken or dirty items (linens with blood stains and a foam mattress).”

“We had a broken toilet seat.”

“I checked the bed, and noticed the middle legs were broken.”

“A stack of bricks [were put] on one corner of one of the beds to replace a broken leg.”

“Nonworking TV.”

“The washer and dryer didn’t work.”

“The washer was not working.”

“The air conditioning on the first floor was not working.”

“As we were listening to him, another man who did not identify himself and was dressed in track pants and t-shirt came out of nowhere in a very aggressive way and started demanding that I, a female, leave our room and go with him to the front gate of the property to show him the code we had tried to use that wasn’t working.”

“The maintenance worker put his hand on this man’s shoulder to hold him back and calm him down because he was acting so aggressive and uncontrollable.”

“Host was over aggressive.”

“I find it disappointing that Airbnb would be okay for a host to have an active recording camera in the living room, violating one’s privacy, and the fact that they find it okay with a host having a listing that nasty.”

“Unauthorised people are just letting themselves onto the property, opening the backyard gate and walking in, totally ignoring me, but, once confronted, they run away. I’ve rented this property for a month and what privacy do I get? These trespassers are jeopardising the well-being of my beloved pooch from escaping. They are trespassing on private property and leaving the backyard fence open while doing so.”

“I always put my zipper on my backpack or suitcase in a certain position. It had moved. He didn’t take anything, because I took all my valuables with me in a second backpack. But that’s a huge violation. The only lock that worked on the bedroom door was a keypad lock that he said didn’t work, but I didn’t know if he could put in a battery from the outside and try to get in. When I came in the doorknob was loose and I couldn’t turn it to get back into my room. I kept turning until it tightened and I was able to get in. Because of the lock, I had to put a table against the door and sleep in my clothes, all packed in case I had to leave in a moment’s notice.”

‘He lied. There were multiple codes to enter the elevator and the unit that didn’t work all the time either. There were also signs posted at the elevators stating that they do not allow Airbnb.’

‘The Airbnb Plus property is located in a building that does not allow short-term rentals. We had to constantly lie to the concierge and every time we parked our car in the garage.’

‘I am at a loss how people can be like this and rip people off and lie so blatantly.’

“We did not want to endanger their lives by going to our Airbnb with active threats of violence in the area we would have to cross through.”

“The neighborhood is trashy, unkept, and very noisy with neighbors consistently slamming doors, babies crying, chickens crowing at all hours of the day, as well as other things.”

“When we arrived we were shocked and disturbed. The apartment was in an unsafe-looking neighborhood in what looked like Section 8 housing.”

“We noticed a homeless person screaming and doing her business in public.”

“[The host] just left out that the home is surrounded by homeless people, tents, trash, and the walk might be one of a lifetime.”

“We found [our dog] three days later torn apart by a coyote.”

“A crazy drunk neighbor with a dog who bit my child and who killed a hen in front of our eyes.”

“Problems with the host and his large dog.”

“They had dogs that barked and might bite.”

“While spending time at the pool the first day at the property, a huge rodent (rat) ran right by me.”

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guttentag, D. Progress on Airbnb: A literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 814–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airbnb. About Us. Available online: https://news.airbnb.com/about-us/ (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Lopes, H.D.S.; Remoaldo, P.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. How the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation has responded to COVID-19. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 8, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNatale, S.; Lewis, R.; Parker, R. Short-term rentals in small cities in Oregon: Impacts and regulations. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, C.; Lutz, C.; Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Jones, B.; Majetić, F.; Perez-Vega, R. Perceived Impacts of Short-Term Rentals in the Local Community in the UK. Peer-to-Peer Accommodation and Community Resilience: Implications for Sustainable Development; CABI: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; Chapter 5; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, K.; Kung, E.; Proserpio, D. The Effect of Home-Sharing on House Prices and Rents: Evidence from Airbnb. Mark. Sci. 2021, 40, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Exploring the relationship between satisfaction, trust and switching intention, repurchase intention in the context of Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Perramon, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Shedding light on sharing ECONOMY and new materialist consumption: An empirical approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Coghlan, A.; Jin, X. Understanding the drivers of Airbnb discontinuance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 80, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.R.; Jones, V.C.; Gielen, A. Reported fire safety and first-aid amenities in Airbnb venues in 16 American cities. Inj. Prev. 2018, 25, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, J. Home, Work and Health in the Airbnb System. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, USA, 2018. UWSpace. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10012/14080 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Wu, C.W.D.; Cheng, W.L.A. Differences in perception on safety and security by travellers of Airbnb and licensed properties. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3092–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Unique Features of Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks. In Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks: Pushing the Boundaries; Dolnicar, S., Ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Berry, L.L. Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, L.; Gillenson, M.L. Understanding brand fan page followers’ discontinuance motivations: A mixed-method study. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furunes, T.; Mkono, M. Service-delivery success and failure under the sharing economy. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3352–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lahiri, A.; Dogan, O.B. A strategic framework for a profitable business model in the sharing economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 69, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. The Servicescape as an Antecedent to Service Quality and Behavioral Intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.S.C.; Joppe, M. Understanding repurchase intention of Airbnb consumers: Perceived authenticity, electronic word-of-mouth, and price sensitivity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuqair, S.; Pinto, D.C.; Mattila, A.S. Benefits of authenticity: Post-failure loyalty in the sharing economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, X.; Lai, D.; Li, Z. Users and non-users of P2P accommodation: Differences in perceived risks and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Back, R.M.; Bufquin, D.; Baker, C.; Park, J.-Y. Peer-to-peer accommodation amid COVID-19: The effects of Airbnb cleanliness information on guests’ trust and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwe, O. The Covid-19 pandemic and the accommodation sharing sector: Effects and prospects for recovery. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 167, 120733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airbnb. Airbnb’s 5-Step Advanced Cleaning Process. 2022. Available online: https://www.airbnb.es/help/article/2809/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Airbnb Introducing Airbnb enhanced clean. 2022. Available online: https://news.airbnb.com/introducing-airbnb-enhanced-clean/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Taylor, P.L. “Airbnb Just Cracked Down on COVID-19 with Mandatory Global Cleaning and Safety Protocols: Why Did It Take So Long?”. Forbes, 23 October 2020. Available online: www.forbes.com/sites/petertaylor/2020/10/23/airbnb-just-cracked-down-on-covid-19-with-mandatory-globalcleaning-and-safety-protocols-why-did-it-take-so-long/?sh=6ddf0ef95d0b (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Jiang, W.; Shum, C.; Bai, B.; Erdem, M. P2P accommodation motivators and repurchase intention: A comparison of indirect and total effects before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 688–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, J.; Morrison, A.M. Developing a scale to measure tourist perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1232–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Huang, S.; Huang, D. Perceived barriers and negotiation of using peer-to-peer accommodation by Chinese consumers in the COVID-19 context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, M.A.; Marques, C. Peer-to-peer accommodation in the time of COVID-19: A segmentation approach from the perspective of tourist safety. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnera, S.M.; Stewart, E. Navigating hotel operations in times of COVID-19. Boston Hosp. Rev. 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. The effect of the COVID-19 on sharing economy activities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 280, 124782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. A netnographic examination of travelers’ online discussions of risks. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2-3, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airbnbhell. Airbnbhell Uncensored Airbnb Stories from Hosts & Guest. 2022. Available online: https://www.airbnbhell.com/ (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Ert, E.; Fleischer, A. What do Airbnb hosts reveal by posting photographs online and how does it affect their perceived trustworthiness? Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Borrajo-Millán, F.; Yi, L. Are Social Media Data Pushing Overtourism? The Case of Barcelona and Chinese Tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M. To use or not use car sharing mobility in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic? Identifying sharing mobility behaviour in times of crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlicz, A.; Petaković, E.; Hrgović, A.-M.V. Beyond Airbnb. Determinants of Customer Satisfaction in P2P Accommodation in Time of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.K.; Bolton, R.N. The Effect of Customers’ Emotional Responses to Service Failures on Their Recovery Effort Evaluations and Satisfaction Judgments. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkala, T.; Rosenström, T.; Kantele, A. A Two-Week Vacation in the Tropics and Psychological Well-Being—An Observational Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M. Could Failures in Peer to Peer Accommodation Be a Threat to Public Health and Safety? An Analysis of Users Experiences after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032158

Alonso-Almeida MdM. Could Failures in Peer to Peer Accommodation Be a Threat to Public Health and Safety? An Analysis of Users Experiences after the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032158

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonso-Almeida, Maria del Mar. 2023. "Could Failures in Peer to Peer Accommodation Be a Threat to Public Health and Safety? An Analysis of Users Experiences after the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032158

APA StyleAlonso-Almeida, M. d. M. (2023). Could Failures in Peer to Peer Accommodation Be a Threat to Public Health and Safety? An Analysis of Users Experiences after the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032158