Validation of a Questionnaire to Analyze Teacher Training in Inclusive Education in the Area of Physical Education: The CEFI-R Questionnaire

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

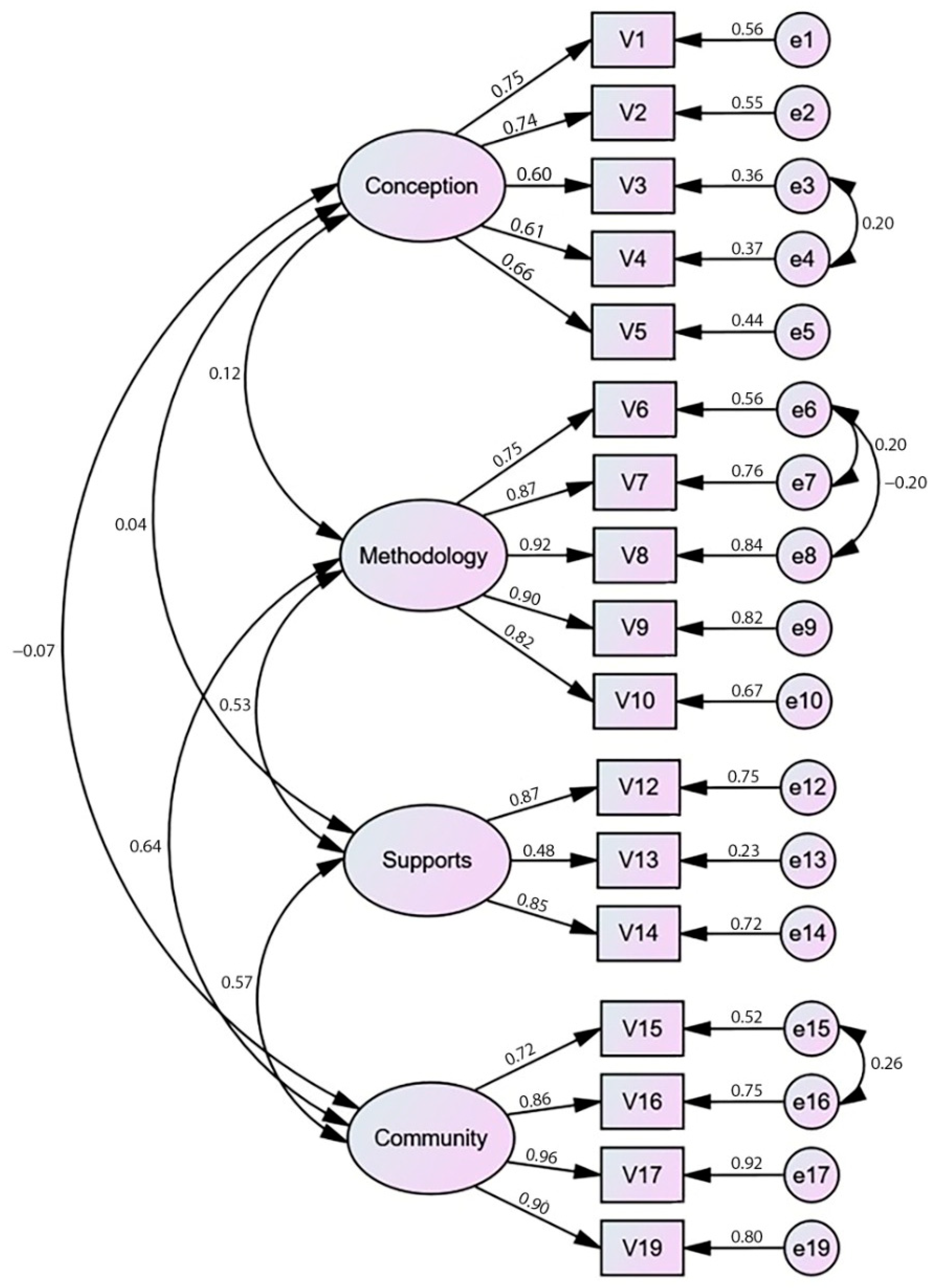

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Lines

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Muntaner Guasp, J.J.; Rosselló Ramón, M.R.; De la Iglesia Mayol, B. Buenas Prácticas En Educación Inclusiva. Educ. Siglo XXI 2016, 34, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amor, A.M.; Hagiwara, M.; Shogren, K.A.; Thompson, J.R.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Burke, K.M.; Aguayo, V. International Perspectives and Trends in Research on Inclusive Education: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Robles-Bello, M.A. Inclusión Como Clave de Una Educación Para Todos: Revisión Teórica / Inclusion as Key to Education for All: A Theoretical Review. REOP—Rev. Esp. Orientación Psicopedag. 2014, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurth, J.A.; Gross, M. The Inclusion Toolbox: Strategies and Techniques for All Teachers; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4833-4415-7. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education; UNESCO: Salamanca, Spain, 1994; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Echeita Sarrionandia, G.; Simón Rueda, C.; Márquez Vázquez, C.; Fernández Bláz, M.L.D.l.M.; Pérez De La Merced, E.; Moreno Hernández, A. Análisis y Valoración Del Área de Educación Del III Plan de Acción Para Personas Con Discapacidad En La Comunidad de Madrid (2012-2015). Siglo Cero Rev. Esp. Sobre Discapac. Intelect. 2017, 48, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.; Pijl, S.J.; Minnaert, A. Regular Primary Schoolteachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Glenn, C.; McGhie-Richmond, D. The Supporting Effective Teaching (SET) Project: The Relationship of Inclusive Teaching Practices to Teachers’ Beliefs about Disability and Ability, and about Their Roles as Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, H.; Polyzopoulou, K. Greek Teachers’ Attitudes toward the Inclusion of Students with Special Educational Needs. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhie-Richmond, D.; Underwood, K.; Jordan, A. Developing Effective Instructional Strategies for Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms. Except. Educ. Can. 2007, 17, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laarhoven, T.R.; Munk, D.D.; Lynch, K.; Bosma, J.; Rouse, J. A Model for Preparing Special and General Education Preservice Teachers for Inclusive Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2007, 58, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokdere, M. A Comparative Study of the Attitude, Concern, and Interaction Levels of Elementary School Teachers and Teacher Candidates towards Inclusive Education. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 2800–2806. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.; Petrenchik, T.; Law, M.; Hurley, P. The Enjoyment of Formal and Informal Recreation and Leisure Activities: A Comparison of School-aged Children with and without Physical Disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2009, 56, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertills, K.; Granlund, M.; Dahlström, Ö.; Augustine, L. Relationships between Physical Education (PE) Teaching and Student Self-Efficacy, Aptitude to Participate in PE and Functional Skills: With a Special Focus on Students with Disabilities. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 2018, 23, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J. Let’s Get Physical: A Public Health Priority. Perspect. Public Health 2013, 133, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, W. Inclusive and Accessible Physical Education: Rethinking Ability and Disability in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Ha, A.S. Inclusion in Physical Education: A Review of Literature. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2012, 59, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C.; Block, M.; Park, J.Y. The Impact of Paralympic School Day on Student Attitudes Toward Inclusion in Physical Education. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. APAQ 2015, 32, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tant, M.; Watelain, E. Forty Years Later, a Systematic Literature Review on Inclusion in Physical Education (1975–2015): A Teacher Perspective. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, B.; Ullenhag, A.; Keen, D.; Granlund, M.; Imms, C. The Effect of Interventions Aimed at Improving Participation Outcomes for Children with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, D.; Nalbant, S.; Aǧlamıș, E.; Baran, F.; Kaya Samut, P.; Aktop, A.; Hutzler, Y. Physical Education Teachers’ Attitudes towards Children with Intellectual Disability: The Impact of Time in Service, Gender, and Previous Acquaintance: Teacher Attitudes Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 57, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, S.R.; Davis, R.; Woodard, R.; Sherrill, C. Comparison of Practicum Types in Changing Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes and Perceived Competence. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2002, 19, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haycock, D.; Smith, A. Still ‘More of the Same for the More Able?’ Including Young Disabled People and Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Extra-Curricular Physical Education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2011, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersman, B.L.; Hodge, S.R. High School Physical Educators’ Beliefs About Teaching Differently Abled Students in an Urban Public School District. Educ. Urban Soc. 2010, 42, 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, B.; Boswell, B. Teachers’ Perceptions, Teaching Practices, and Learning Opportunities for Inclusion. Phys. Educ. 2013, 70, 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer, V.; Valkanover, S.; Eckhart, M.; Nagel, S. The Role of Teaching Strategies in Social Acceptance and Interactions; Considering Students With Intellectual Disabilities in Inclusive Physical Education. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 586960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pit-ten Cate, I.M.; Markova, M.; Krischler, M.; Krolak-Schwerdt, S. Promoting Inclusive Education: The Role of Teachers’ Competence and Attitudes. Insights Learn. Disabil. 2018, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Arini, F.D.; Sunardi, S.; Yamtinah, S. Social Skills of Students with Disabilities at Elementary Level in Inclusive School Setting. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2019, 6, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, K. Developing Principles of Practice for Implementing Models-Based Practice: A Self-Study of Physical Education Teacher Education Practice. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2021, 41, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, A.; Schwab, S. Parents’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education and Their Perceptions of Inclusive Teaching Practices and Resources. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pocock, T.; Miyahara, M. Inclusion of Students with Disability in Physical Education: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, D.; MacDonald, W.; Carroll, E.; Moody, B. Pre-Service Teachers’ Attitudes towards Children with Disabilities: An Irish Perspective. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, A.; Rizzo, T.L. Disability Labels Affect Physical Educators. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2006, 23, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, T.L.; Vispoel, W.P. Physical Educators’ Attributes and Attitudes Toward Teaching Students with Handicaps. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1991, 8, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Manzano-Redondo, F.; Adsuar, J.C.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Gomez-Paniagua, S.; Barrios-Fernandez, S. Spanish Physical Education Teachers’ Perceptions about Their Preparation for Inclusive Education. Children 2022, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, E.N. Designing Inclusive Physical Education with Universal Design for Learning. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2019, 90, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston-Wilson, C.; Lieberman, L.J. A Needs Assessment for Inclusive Physical Education: A Tool for Professional Development. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2020, 91, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, L.; Brian, A.; Grenier, M. The Lieberman–Brian Inclusion Rating Scale for Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braksiek, M.; Gröben, B.; Rischke, A.; Heim, C. Teachers’ Attitude toward Inclusive Physical Education and Factors That Influence It. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2019, 49, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selickaitė, D.; Hutzler, Y.; Pukėnas, K.; Block, M.E.; Rėklaitienė, D. The Analysis of the Structure, Validity, and Reliability of an Inclusive Physical Education Self-Efficacy Instrument for Lithuanian Physical Education Teachers. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 215824401985247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Gil, F.; Martín-Pastor, E.; Orgaz Baz, B.; Poy Castro, R. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Evaluate Teacher Training for Inclusion: The CEFI-R. Aula Abierta 2019, 48, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Gomez-Paniagua, S.; Barrios-Fernandez, S.; Garcia-Gomez, A.; Adsuar, J.; Sáez-Padilla, J.; Muñoz-Bermejo, L. Psychometric Properties of a Questionnaire to Assess Spanish Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions about Their Preparation for Inclusive Education. Healthcare 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkind, N.J.; Escalona, R.L.; Valdés Salmerón, V. Métodos de investigación; Prentice-Hall: Mexico City, México, 1999; ISBN 978-970-17-0234-5. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. Profile of Inclusive Teacher; European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education: Odense, Denmark, 2012; ISBN 978-87-7110-316-8. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T.; Ainscow, M. Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools, 3rd ed.; Substantially Revised and Expanded; Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education: Bristol, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-872001-68-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.; Kanuka, H. E-Research: Methods, Strategies, and Issues; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-205-34382-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, Development and Future Directions. Psicothema 2017, 29, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U. SOLOMON: A Method for Splitting a Sample into Equivalent Subsamples in Factor Analysis. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 54, 2665–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paatero, P. Least Squares Formulation of Robust Non-Negative Factor Analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1997, 37, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. Robust Promin: A Method for Diagonally Weighted Factor Rotation. Lib. Rev. Peru. Psicol. 2019, 25, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata-Ramírez, M.d.l.Á.; Holgado-Tello, F.P. Construct Validity of Likert Scales through Confirmatory Factor Analysis: A Simulation Study Comparing Different Methods of Estimation Based on Pearson and Polychoric Correlations. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2013, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, S.; Jahng, S. Determining the Number of Factors Using Parallel Analysis and Its Recent Variants. Psychol. Methods 2019, 24, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C. A Review of Exploratory Factor Analysis Decisions and Overview of Current Practices: What We Are Doing and How Can We Improve? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2016, 32, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costales, J.; Catulay, J.J.J.; Costales, J.; Bermudez, N. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Factor Analysis: A Quantitative Approach on Mobile Gaming Addiction Using Random Forest Classifier. In Proceedings of the 2022 the 6th International Conference on Information System and Data Mining, Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 27–29 May 2022; ACM: Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. A Guide on the Use of Factor Analysis in the Assessment of Construct Validity. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2013, 43, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F. (Ed.) Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Rosseel, Y. Assessing Fit in Ordinal Factor Analysis Models: SRMR vs. RMSEA. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2020, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; DiStefano, C. The Relationship Between the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual and Model Misspecification in Factor Analysis Models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.H.; Yoon, M. A Modified Comparative Fit Index for Factorial Invariance Studies. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2015, 22, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadama, G.N.; Pandey, S. Effect of Sample Size on Goodness-Fit of-Fit Indices in Structural Equation Models. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1995, 20, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado–Tello, F.P.; Chacón–Moscoso, S.; Barbero–García, I.; Vila–Abad, E. Polychoric versus Pearson Correlations in Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Variables. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Christoffersson, A. Simultaneous Factor Analysis of Dichotomous Variables in Several Groups. Psychometrika 1981, 46, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, E.B.; Saraswathi, D.A.B. Literature Review Of Cronbachalphacoefficient (A) And Mcdonald’s Omega Coefficient (Ω). Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-81190-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marron, S.; Murphy, F.; O’Keeffe, M. Providing “Good Day” Physical Education Experiences for Children with SEN in Mainstream Irish Primary Schools. REACH J. Incl. Educ. Irel. 2013, 26, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T.; Haegele, J.A. Graduate Students’ Practicum Experiences Instructing Students with Severe and Profound Disabilities in Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2017, 23, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, H.; Wrench, A.; Garrett, R. Pedagogies for Inclusion of Junior Primary Students with Disabilities in PE. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 2017, 22, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluijt, D.; Bakker, C.; Struyf, E. Team-Reflection: The Missing Link in Co-Teaching Teams. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G.; Causton, J. Leading Inclusive Reform for Students With Disabilities: A School- and Systemwide Approach. Theory Pract. 2014, 53, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, H.; McCafferty, A.; Quayle, E.; McKenzie, K. Review: Typically-Developing Students’ Views and Experiences of Inclusive Education. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossaert, G.; Colpin, H.; Pijl, S.J.; Petry, K. Truly Included? A Literature Study Focusing on the Social Dimension of Inclusion in Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, H.; Bosker, R.J.; van der Werf, M.P.C. Sustainability of Teacher Expectation Bias Effects on Long-Term Student Performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A. What Factors Influence the Decisions of Parents of Children with Special Educational Needs When Choosing a Secondary Educational Provision for Their Child at Change of Phase from Primary to Secondary Education? A Review of the Literature. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2013, 13, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soodak, L.C.; Podell, D.M.; Lehman, L.R. Teacher, Student, and School Attributes as Predictors of Teachers’ Responses to Inclusion. J. Spec. Educ. 1998, 31, 480–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, R.; Ferriz, R.; Roldan, A. Validation of a Physical Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Instrument Toward Inclusion of Students With Disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudláček, M.; Baloun, L.; Ješina, O. The Development and Validation of Revised Inclusive Physical Education Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Czech Physical Education Majors. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, T.; Chapman, S.; Piggott, B. Inclusion Illusion: A Mixed-Methods Study of Preservice Teachers and Their Preparedness for Inclusive Schooling in Health and Physical Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, J.; Sáez-Gallego, N.M.; Reina, R.; Ferriz, R.; Navarro-Patón, R. Perception of Self-Eficacy towards Inclusion in Pre-Service Teachers of Physical Education. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2019, 28, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, W.J.; Theriot, E.A.; Haegele, J.A. Attempting Inclusive Practice: Perspectives of Physical Educators and Adapted Physical Educators. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 2020, 11, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 638 | 80.9 |

| Women | 151 | 19.1 | |

| Center Province | Cáceres | 211 | 26.7 |

| Badajoz | 578 | 73.3 | |

| Studies at University of Extremadura | Yes | 54 | 17.8 |

| No | 78 | 25.7 | |

| Age | Below 30 | 79 | 10.0 |

| Between 30 and 40 | 253 | 32.1 | |

| Between 40 and 50 | 267 | 33.8 | |

| Over 50 | 190 | 24.1 |

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I would prefer to have students with specific educational needs in my classroom. | 0.790 | 0.011 | −0.022 | 0.058 |

| 2. A child with specific educational support needs does not disrupt the classroom routine and disrupt the learning of his/her classmates. | 0.788 | −0.023 | 0.038 | 0.050 |

| 3. We should place students with special educational needs in mainstream schools even if we do not have the appropriate preparation to do so. | 0.604 | 0.030 | −0.060 | −0.004 |

| 4. Students with specific educational support needs can follow the day-to-day curriculum. | 0.708 | 0.039 | 0.121 | −0.208 |

| 5. I am not worried that my workload will increase if I have students with specific educational supports needs in my class. | 0.684 | −0.029 | −0.050 | 0.108 |

| 6. I know how to teach each of my students differently according to their characteristics. | 0.003 | 0.849 | −0.011 | −0.017 |

| 7. I know how to design teaching units and lessons with the diversity of students in mind. | 0.022 | 0.977 | −0.053 | −0.024 |

| 8. I know how to adapt the way I assess the individual needs of each of my students. | 0.021 | 0.975 | −0.035 | 0.014 |

| 9. I know how to handle and adapt teaching materials to respond to the needs of each of my students. | 0.027 | 0.922 | 0.033 | −0.003 |

| 10. I can adapt my communication techniques to ensure that all students can be successfully included in the mainstream classroom. | −0.046 | 0.810 | 0.061 | 0.070 |

| 11. Joint teacher-support teacher planning would make it easier for support to be provided within the classroom. | −0.077 | 0.290 | 0.377 | 0.362 |

| 12. I believe that the best way to provide support for students is for the support teacher to be embedded in the classroom, rather than in the support classroom. | −0.006 | 0.047 | 0.709 | 0.165 |

| 13. The role of the support teacher is to work with the whole class. | 0.021 | −0.005 | 0.494 | 0.011 |

| 14. I consider that the place of the support teacher is in the regular classroom with each of the teachers. | −0.026 | −0.012 | 1.004 | −0.033 |

| 15. The educational projects should be reviewed with the participation of the different agents of the educational community (teachers, parents, students). | 0.071 | −0.028 | 0.204 | 0.702 |

| 16. There must be a very close relationship between the teaching staff and the rest of the educational agents (AMPA, neighbourhood associations, school council…). | 0.027 | −0.042 | −0.009 | 0.979 |

| 17. The school must encourage the involvement of parents and the community. | 0.006 | 0.046 | −0.027 | 0.951 |

| 18. Each member of the school (teachers, parents, students, other professionals) is a fundamental element of the school. | −0.053 | 0.154 | 0.097 | 0.837 |

| 19. The school must work together with the resources of the neighbourhood. | −0.001 | 0.055 | 0.006 | 0.908 |

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 0.65 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 0.44 | 0.497 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 7 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.85 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 9 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 10 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 11 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 12 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 13 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 14 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 1.00 | |||||

| 15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 1.00 | ||||

| 16 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.57 | 0.80 | 1.00 | |||

| 17 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.92 | 1.00 | ||

| 18 | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 1.00 | |

| 19 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I would prefer to have students with specific educational needs in my classroom. | 0.788 | |||

| 2. A child with specific educational support needs does not disrupt the classroom routine and disrupt the learning of his/her classmates. | 0.788 | |||

| 3. We should place students with special educational needs in mainstream schools even if we do not have the appropriate preparation to do so. | 0.603 | |||

| 4. Students with specific educational support needs can follow the day-to-day curriculum. | 0.711 | |||

| 5. I am not worried that my workload will increase if I have students with specific educational supports needs in my class. | 0.682 | |||

| 6. I know how to teach each of my students differently according to their characteristics. | 0.849 | |||

| 7. I know how to design teaching units and lessons with the diversity of students in mind. | 0.977 | |||

| 8. I know how to adapt the way I assess the individual needs of each of my students. | 0.977 | |||

| 9. I know how to handle and adapt teaching materials to respond to the needs of each of my students. | 0.925 | |||

| 10. I can adapt my communication techniques to ensure that all students can be successfully included in the mainstream classroom. | 0.814 | |||

| 11. Joint teacher-support teacher planning would make it easier for support to be provided within the classroom. | Excluded | |||

| 12. I believe that the best way to provide support for students is for the support teacher to be embedded in the classroom, rather than in the support classroom. | 0.727 | |||

| 13. The role of the support teacher is to work with the whole class. | 0.489 | |||

| 14. I consider that the place of the support teacher is in the regular classroom with each of the teachers. | 1.004 | |||

| 15. The educational projects should be reviewed with the participation of the different agents of the educational community (teachers, parents, students). | 0.679 | |||

| 16. There must be a very close relationship between the teaching staff and the rest of the educational agents (AMPA, neighbourhood associations, school council…). | 0.977 | |||

| 17. The school must encourage the involvement of parents and the community. | 0.930 | |||

| 18. Each member of the school (teachers, parents, students, other professionals) is a fundamental element of the school. | Excluded | |||

| 19. The school must work together with the resources of the neighbourhood. | 0.868 | |||

| Factor 1 Conception of Diversity | Factor 2 Methodology | Factor 3 Support | Factor 4 Community Participation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Conception of Diversity | 1 | |||

| Factor 2 Methodology | 0.135 | 1 | ||

| Factor 3 Support | 0.049 | 0.404 | 1 | |

| Factor 4 Community Participation | 0.038 | 0.542 | 0.625 | 1 |

| Indices | Value |

|---|---|

| RMSEA | 0.045 |

| RMSR | 0.039 |

| NFI | 0.956 |

| NNFI | 0.980 |

| Ρ (χ2) | 0.99 |

| CMIN/DF | 1.803 |

| Factor 1 Conception of Diversity | Factor 2 Methodology | Factor 3 Supports | Factor 4 Community Participation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.803 | 0.934 | 0.807 | 0.923 |

| McDonald’s Omega | 0.812 | 0.935 | 0.815 | 0.924 |

| Explained Variance | 2.597 | 4.439 | 2.288 | 3.556 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojo-Ramos, J.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Gómez-Paniagua, S.; García-Gordillo, M.Á.; Denche-Zamorano, Á.; Pérez-Gómez, J. Validation of a Questionnaire to Analyze Teacher Training in Inclusive Education in the Area of Physical Education: The CEFI-R Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032306

Rojo-Ramos J, Mendoza-Muñoz M, Gómez-Paniagua S, García-Gordillo MÁ, Denche-Zamorano Á, Pérez-Gómez J. Validation of a Questionnaire to Analyze Teacher Training in Inclusive Education in the Area of Physical Education: The CEFI-R Questionnaire. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032306

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojo-Ramos, Jorge, María Mendoza-Muñoz, Santiago Gómez-Paniagua, Miguel Ángel García-Gordillo, Ángel Denche-Zamorano, and Jorge Pérez-Gómez. 2023. "Validation of a Questionnaire to Analyze Teacher Training in Inclusive Education in the Area of Physical Education: The CEFI-R Questionnaire" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032306