The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

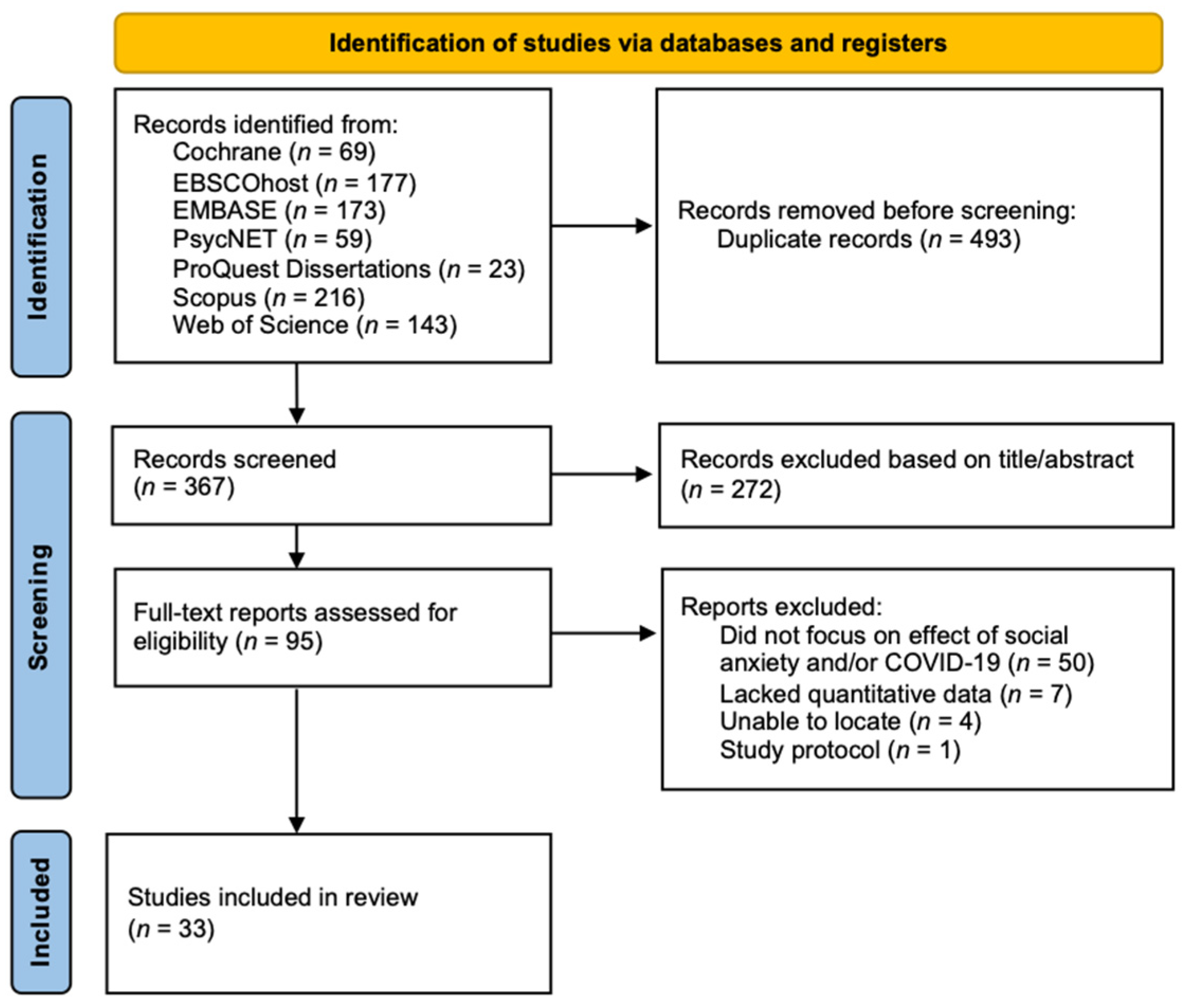

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.3. Search Results

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Study Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Summary Descriptions

3.2. Methodological Quality

3.3. Social Anxiety in the General Population Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.4. Social Anxiety in Specific Populations due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.4.1. Gender Effects

3.4.2. Financial Stress

3.5. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Individuals with SAD

3.6. Risk and Protective Factors Influencing Social Anxiety Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.6.1. Contracting COVID-19

3.6.2. Socio-Emotional Well-Being and Coping Style

3.6.3. Social Networks and Friendships

3.6.4. Student/Work Mode

3.7. Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic due to Social Anxiety

3.7.1. Educational Environments

3.7.2. COVID-19 Knowledge

3.7.3. Social Media

3.7.4. COVID-Related Anxiety and Worry

3.7.5. Affiliative Responses

3.7.6. Loneliness and Friendship

3.7.7. Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and Stress during Lockdowns

3.7.8. Mental Health Outcomes during Easing of Restrictions

3.7.9. Influence of Pre-Lockdown Social Anxiety on Self Care during Lockdown

4. Limitations of Existing Research and Directions for Future Research

5. Clinical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item is Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Page 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Page 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Pages 1–2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Page 2 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Page 3 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Page 3 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Page 3 and Appendix A |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 4 |

| Data items | 10 a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Appendix C |

| 10 b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Appendix C | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 4 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | Page 4 |

| Synthesis methods | 13 a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Not Applicable |

| 13 b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics or data conversions. | Not Applicable | |

| 13 c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display the results of individual studies and syntheses. | Not Applicable | |

| 13 d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Not Applicable | |

| 13 e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | Not Applicable | |

| 13 f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | Not Applicable | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Page 4 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Page 5–19 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16 a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Page 3 |

| 16 b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Not Applicable | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Table 1 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of the risk of bias for each included study. | Table 1 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Page 5–19 |

| Results of syntheses | 20 a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Not Applicable |

| 20 b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was conducted, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | Not Applicable | |

| 20 c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Not Applicable | |

| 20 d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | Not Applicable | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of the risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | Page 4 |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | Page 5–19 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23 a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Page 5–19 |

| 23 b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Page 19–20 | |

| 23 c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Page 19–20 | |

| 23 d | Discuss the implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Page 19–20 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24 a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | Page 3 |

| 24 b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed or state that a protocol was not prepared. | Page 3 | |

| 24 c | Describe and explain any amendments to the information provided at registration or in the protocol. | Not Applicable | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Page 24 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Page 24 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C |

Appendix B

| Database | Search String | Hits | Search Date (dd/mm/yyyy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBSCOhost | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (All fields) | 69 | 1 September 2021 |

| 56 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 41 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 11 | 1 October 2022 | ||

| EMBASE | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (Title/Abstract) | 74 | 1 September 2021 |

| 27 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 49 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 23 | 1 October 2022 | ||

| Cochrane | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (Title or Abstract or Keyword) | 4 | 1 September 2021 |

| 63 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 0 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 2 | 1 October 2022 | ||

| Proquest Dissertations and Theses | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (Document title or Abstract) | 8 | 1 September 2021 |

| 0 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 3 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 12 | 1 October 2022 | ||

| PsycNET | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (Any Field) | 19 | 1 September 2021 |

| 9 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 11 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 20 | 1 October 2022 | ||

| Scopus | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (Title/Abstract/Keywords) | 96 | 1 September 2021 |

| 33 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 68 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 19 | 1 October 2022 | ||

| Web of Science | (“Social Anxiety” OR “Social phob*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “Coronavirus” OR “Pandemic” OR “Lockdown”) (Topic) | 53 | 1 September 2021 |

| 46 | 1 March 2022 | ||

| 31 | 1 August 2022 | ||

| 13 | 1 October 2022 |

Appendix C

| PICO Elements | Description |

|---|---|

| Aim 1: The incidence of social anxiety within the general population because of the COVID-19 pandemic. | |

| Population/Condition | All individuals affected by the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Interventions | Onset of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Comparator | Not applicable to the general population.Subpopulations include adults vs. children/adolescents, Socio-Economic Status, men vs. women, gender diverse vs. gender conforming) |

| Outcomes of interest | Social anxiety measures |

| Type of studies | Longitudinal studies, naturalistic observation studies, retrospective studies, prognostic studies, prevalence studies, repeated cross-sectional studies |

| Aim 2: How COVID-19 has affected individuals with a clinical diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder | |

| Population/Condition | Individuals with a diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder or who self-identify as having Social Anxiety Disorder |

| Interventions | Onset of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Comparator | Comparators may include Individuals with no diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder |

| Outcomes of interest | All patient-oriented mental health outcomes |

| Type of studies | Comparative studies, longitudinal studies, naturalistic observation studies, retrospective studies, repeated cross-sectional studies, prognostic studies |

| Aim 3: Risk and protective factors that may have influenced levels of social anxiety in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| Population/Condition | All individuals affected by the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Interventions | Onset of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Comparator | Individuals with differential scores on outcomes related to risk and protective factors |

| Outcomes of interest | Social anxiety measures |

| Type of studies | All study designs |

| Aim 4: How social anxiety has influenced affective, behavioural, and cognitive responses to the COVID-19 environment. | |

| Population/Condition | Individuals experiencing social anxiety during the pandemic |

| Interventions | Not Applicable |

| Comparator | Individuals with differential scores on social anxiety |

| Outcomes of interest | All patient-oriented mental health outcomes |

| Type of studies | All study designs |

References

- Elbay, R.Y.; Kurtulmuş, A.; Arpacıoğlu, S.; Karadere, E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in COVID-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Herrera, A.M.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana-Domeque, C.; Proto, E. On the Persistence of Mental Health Deterioration during the COVID-19 Pandemic by Sex and Ethnicity in the UK: Evidence from Understanding Society. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 22, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderka, I.M.; McLean, C.P.; Huppert, J.D.; Davidson, J.R.; Foa, E.B. Fear, avoidance and physiological symptoms during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. 2013, 51, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, F.R.; Rum, R.; Silva, G.; Kashdan, T.B. Are people with social anxiety happier alone? J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 84, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eres, R.; Lim, M.H.; Lanham, S.; Jillard, C.; Bates, G. Loneliness and emotion regulation: Implications of having social anxiety disorder. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, C.A.; Schmidt, L.A. Social anxiety disorder: A review of environmental risk factors. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bareeqa, S.B.; Ahmed, S.I.; Samar, S.S.; Yasin, W.; Zehra, S.; Monese, G.M.; Gouthro, R.V. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in china during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2021, 56, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønderskov, K.M.; Dinesen, P.T.; Santini, Z.I.; Østergaard, S.D. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020, 32, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawel, A.; Shou, Y.; Smithson, M.; Cherbuin, N.; Banfield, M.; Calear, A.L.; Farrer, L.M.; Gray, D.; Gulliver, A.; Housen, T.; et al. The Effect of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Representative Sample of Australian Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Kang, D.; Zeng, Q. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Chinese Graduate Students’ Learning Activities: A Latent Class Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 877106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Wang, M.; Song, T.; Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, L.; Yan, L. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cost, K.T.; Crosbie, J.; Anagnostou, E.; Birken, C.S.; Charach, A.; Monga, S.; Kelley, E.; Nicolson, R.; Maguire, J.L.; Burton, C.L.; et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; text rev.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shengbo, L.; Fiaz, M.; Mughal, Y.H.; Wisetsri, W.; Ullah, I.; Ren, D.D.; Kiran, A.; Kesari, K.K. Impact of Dark Triad on Anxiety Disorder: Parallel Mediation Analysis During Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 914328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R. Responses to Social Exclusion: Social Anxiety, Jealousy, Loneliness, Depression, and Low Self-Esteem; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 9, pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Reinelt, E.; Aldinger, M.; Stopsack, M.; Schwahn, C.; John, U.; Baumeister, S.E.; Grabe, H.J.; Barnow, S. High social support buffers the effects of 5-HTTLPR genotypes within social anxiety disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 264, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.D.; Maciel, I.V.; Johnson, D.M.; Ciepluch, I. Social Anxiety and Perceived Social Support: Gender Differences and the Mediating Role of Communication Styles. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriends, N.; Bolt, O.C.; Kunz, S.M. Social anxiety disorder, a lifelong disorder? A review of the spontaneous remission and its predictors. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambusaidi, A.; Al-Huseini, S.; Alshaqsi, H.; AlGhafri, M.; Chan, M.-F.; Al-Sibani, N.; Al-Adawi, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W. The Prevalence and Sociodemographic Correlates of Social Anxiety Disorder: A Focused National Survey. Chronic Stress 2022, 6, 24705470221081215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Han, X.H.; Yang, Z.P.; Zhao, Z.J. Family Function, Loneliness, Emotion Regulation, and Hope in Secondary Vocational School Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Stein, D.J.; Lim, C.C.W.; Roest, A.M.; de Jonge, P.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.J.; Bruffaerts, R.; et al. The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: Data from the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, G.M.; Tavares, V.D.O.; de Meiroz Grilo, M.L.P.; Coelho, M.L.G.; de Lima-Araújo, G.L.; Schuch, F.B.; Galvão-Coelho, N.L. Mental Health in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Review of Prevalence Meta-Analyses. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 703838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniuka, A.R.; Cramer, R.J.; Wilsey, C.N.; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J.; Mennicke, A.; Patton, A.; Zarwell, M.; McLean, C.P.; Harris, Y.J.; Sullivan, S.; et al. COVID-19 Exposure, Stress, and Mental Health Outcomes: Results from a Needs Assessment Among Low Income Adults in Central North Carolina. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 790468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A.W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schmidt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Pinto, L.; et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 55, 22–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, F.P.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Khani, S.; Hosseinifard, H.; Tajik, F.; Raoofi, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Aghalou, S.; Torabi, F.; et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Nearchou, F.; Flinn, C.; Niland, R.; Subramaniam, S.S.; Hennessy, E. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, L.; Lee, R. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; AHFMRHTA Initiative20040213, HTA Initiative; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.; Packer, T.L.; Tang, S.H.; Girdler, S. Self-management education programs for age-related macular degeneration: A systematic review. Australas. J. Ageing 2008, 27, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B. Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and confidence intervals for effect sizes. Psychol. Sch. 2007, 44, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Mancebo, M.C.; Moitra, E. Changes in social anxiety symptoms and loneliness after increased isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Lee, P.; Wong, P.W.C. The changes of suicidal ideation status among young people in Hong Kong during COVID-19: A longitudinal survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arad, G.; Shamai-Leshem, D.; Bar-Haim, Y. Social Distancing During A COVID-19 Lockdown Contributes to The Maintenance of Social Anxiety: A Natural Experiment. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2021, 45, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendau, A.; Kunas, S.L.; Wyka, S.; Petzold, M.B.; Plag, J.; Asselmann, E.; Ströhle, A. Longitudinal changes of anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: The role of pre-existing anxiety, depressive, and other mental disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 79, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Belled, A.; Tejada-Gallardo, C.; Torrelles-Nadal, C.; Alsinet, C. The costs of the COVID-19 on subjective well-being: An analysis of the outbreak in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, J.D.; Abarno, C.N.; Lewis, E.M.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Garey, L. Increases in distress during stay-at-home mandates During the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, C.N.; Garcia, K.M.; Andino, M.V.; Ollendick, T.H.; Richey, J.A. Social anxiety disorder is Associated with Vaccination attitude, stress, and coping responses during COVID-19. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022, 46, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaraman, L.; Lynch, A.D.; Richer, A.M.; Zhai, E. Examining early adolescent positive and negative social technology behaviors and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Mind Behav. 2022, 3, 0000062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czorniej, K.P.; Krajewska-Kułak, E.; Kułak, W. Assessment of anxiety disorders in students starting work with coronavirus patients during a pandemic in Podlaskie Province, Poland. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 980361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskiyurt, R.; Alaca, E. Determination of Social Anxiety Levels of Distance Education University Students. Uzak. Eğitim Alan Üniversite Öğrencilerinin Sos. Kaygı Düzeylerinin Belirlenmesi. 2021, 13, 257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Falcó, R.; Vidal-Arenas, V.; Ortet-Walker, J.; Marzo, J.C.; Piqueras, J.A. Fear of COVID-19 and emotional dysfunction problems: Intrusive, avoidance and hyperarousal stress as key mediators. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawwaz, A.N.; Prihadi, K.D.; Purwaningtyas, E.K. Studying online from home and social anxiety among university students: The role of societal and interpersonal mattering. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2022, 11, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 52, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.T.K.; Moscovitch, D.A. The moderating effects of reported pre-pandemic social anxiety, symptom impairment, and current stressors on mental health and affiliative adjustment during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping 2022, 35, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Cao, S.Q.; Zhou, S.K.; Punia, D.; Zhu, X.R.; Luo, Y.J.; Wu, H.Y. How anxiety predicts interpersonal curiosity during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediation effect of interpersonal distancing and autistic tendency. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 180, 110973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, M.H.; Eltannir, E.; Tinawi, H.; Daher, D.; Eltannir, A.; Moukarzel, A.A. Severe Social Anxiety Among Adolescents During COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, N.; Yang, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, B.; Fu, L.; Hu, Y.; Luo, D.; Xiao, X.; Zheng, W.; Xu, H.; et al. Hospitalization, interpersonal and personal factors of social anxiety among COVID-19 survivors at the six-month follow-up after hospital treatment: The minority stress model. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2022, 13, 2019980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvonen, J.; Lessard, L.M.; Kline, N.G.; Graham, S. Young Adult Adaptability to the Social Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Protective Role of Friendships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, M.D.; Roos, Y.; Richter, D.; Wrzus, C. Resuming social contact after months of contact restrictions: Social traits moderate associations between changes in social contact and well-being. J. Res. Personal. 2022, 98, 104223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, T.; Peters, C.; Ertle, A.; Hilbert, K.; Lueken, U. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic related stressors on patients with anxiety disorders: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.M. Influence of the Youth’s Psychological Capital on Social Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak: The Mediating Role of Coping Style. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.Y.; Kang, D.R.; Zhang, M.Q.; Xia, Y.L.; Zeng, Q. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Chinese Postgraduate Students’ Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.H.; Qualter, P.; Thurston, L.; Eres, R.; Hennessey, A.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Lambert, G.W. A Global Longitudinal Study Examining Social Restrictions Severity on Loneliness, Social Anxiety, and Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 818030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Vidal, D.G.; Sousa, H.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Leite, A. Psychological Factors Explaining Perceived Impact of COVID-19 on Travel. Eur. J. Invest. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1120–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeish, A.C.; Walker, K.L.; Hart, J.L. Changes in Internalizing Symptoms and Anxiety Sensitivity Among College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2022, 44, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, S.; Zeytinoglu, S.; Lorenzo, N.E.; Chronis-Tuscano, A.; Degnan, K.A.; Almas, A.N.; Pine, D.S.; Fox, N.A. Which Anxious Adolescents Were Most Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 10, 21677026211059524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, V. Traumatic Intrusion, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms in Individuals Experiencing Interpersonal Violence at Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic; M.A. Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, H. How compulsive WeChat use and information overload affect social media fatigue and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic? A stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 64, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quittkat, H.L.; Düsing, R.; Holtmann, F.J.; Buhlmann, U.; Svaldi, J.; Vocks, S. Perceived Impact of COVID-19 Across Different Mental Disorders: A Study on Disorder-Specific Symptoms, Psychosocial Stress and Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 586246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samantaray, N.N.; Kar, N.; Mishra, S.R. A follow-up study on treatment effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on social anxiety disorder: Impact of COVID-19 fear during post-lockdown period. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 310, 114439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, U. Evaluation of Psychosocial Symptoms in Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey by Comparing Them with the Pre-pandemic Situation and Its Relationship with Quality of Life. Bakirkoy Tip Derg. Med. J. Bakirkoy 2022, 18, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terin, H.; Açıkel, S.B.; Yılmaz, M.M.; Şenel, S. The effects of anxiety about their parents getting COVID-19 infection on children’s mental health. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 182, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurteri, N.; Sarigedik, E. Evaluation of the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep habits and quality of life in children. Ann. Med. Res. 2021, 28, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; He, X.; Fan, G.; Li, L.; Huang, Q.; Qiu, Q.; Kang, Z.; Du, T.; Han, L.; Ding, L.; et al. COVID-19 infection outbreak increases anxiety level of general public in China: Involved mechanisms and influencing factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehl, P.E. Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am. Psychol. 1962, 17, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S.M.; Simons, A.D. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtem, C.M.; Laine, M.L.; Boomsma, D.I.; Ligthart, L.; van Wijk, A.J.; De Jongh, A. A review and meta-analysis of the heritability of specific phobia subtypes and corresponding fears. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.; Asnaani, A.; Aderka, I.M. Gender differences in social anxiety disorder: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballo, V.E.; Salazar, I.C.; Irurtia, M.J.; Arias, B.; Hofmann, S.G. Differences in social anxiety between men and women across 18 countries. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2014, 64, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.T. A point of minimal important difference (MID): A critique of terminology and methods. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2011, 11, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Pierson, E.; Koh, P.W.; Gerardin, J.; Redbird, B.; Grusky, D.; Leskovec, J. Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening. Nature 2021, 589, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biondi, F.; Liparoti, M.; Lacetera, A.; Sorrentino, P.; Minino, R. Risk factors for mental health in general population during SARS-CoV2 pandemic: A systematic review. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Review of the unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the occurrence of eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2022, 35, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, A.S.F.; Pearson, R.M.; Adams, M.J.; Northstone, K.; Tilling, K.; Smith, D.; Fawns-Ritchie, C.; Bould, H.; Warne, N.; Zammit, S.; et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 218, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, R.B.; Charles, E.J.; Mehaffey, J.H. Socio-economic status and COVID-19-related cases and fatalities. Public Health 2020, 189, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, K.; Ayers, C.K.; Kondo, K.K.; Saha, S.; Advani, S.M.; Young, S.; Spencer, H.; Rusek, M.; Anderson, J.; Veazie, S.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19-Related Infections, Hospitalizations, and Deaths: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifman, M.A.; Raifman, J.R. Disparities in the population at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and income. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, M.T.; Homan, A.C. Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: Effective coping and perceived control. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmundson, G.J.G.; Rachor, G.; Drakes, D.H.; Boehme, B.A.E.; Paluszek, M.M.; Taylor, S. How does COVID stress vary across the anxiety-related disorders? Assessing factorial invariance and changes in COVID Stress Scale scores during the pandemic. J. Anxiety Disord. 2022, 87, 102554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Tan, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, X.; Jiang, X.; McIntyre, R.S.; et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Blakey, S.M. , Clinical Handbook of Fear and Anxiety: Maintenance Processes and Treatment Mechanisms; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, P.; Beutel, M.E.; Hoyer, J.; Leibing, E.; Nolting, B.; Salzer, S.; Strauss, B.; Wiltink, J.; Steinert, C.; Leichsenring, F. The role of shame and guilt in social anxiety disorder. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 6, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnúsdóttir, I.; Lovik, A.; Unnarsdóttir, A.B.; McCartney, D.; Ask, H.; Kõiv, K.; Christoffersen, L.A.N.; Johnson, S.U.; Hauksdóttir, A.; Fawns-Ritchie, C.; et al. Acute COVID-19 severity and mental health morbidity trajectories in patient populations of six nations: An observational study. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e406–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelam, K.; Duddu, V.; Anyim, N.; Neelam, J.; Lewis, S. Pandemics and pre-existing mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2021, 10, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Harrison, P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: Retrospective cohort studies of 62354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reblin, M.; Uchino, B.N. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2008, 21, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harandi, T.F.; Taghinasab, M.M.; Nayeri, T.D. The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5212–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ștefan, C.A. Self-compassion as mediator between coping and social anxiety in late adolescence: A longitudinal analysis. J. Adolesc. 2019, 76, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, F.; Johnson, D.C.; Dimoulas, E.; Morgan, C.A.; Charney, D.; Southwick, S. Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Aucoin, P.; Gardam, O.; John, E.S.; Kokenberg-Gallant, L.; Corbeil, S.; Smith, J.; Guimond, F.A. COVID-19-related anxiety and trauma symptoms predict decreases in body image satisfaction in children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneshensel, C.S.; Stone, J.D. Stress and depression: A test of the buffering model of social support. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1982, 39, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Connor-Smith, J.K. Perceived social support, coping, and symptoms of distress in American and Spanish students. Anxiety Stress Coping 2006, 19, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cogn. Behav. 2007, 36, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.; McNally, R.J. Social Anxiety Disorder as a Densely Interconnected Network of Fear and Avoidance for Social Situations. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2018, 42, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.M.; Wells, A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dryman, M.T.; Gardner, S.; Weeks, J.W.; Heimberg, R.G. Social anxiety disorder and quality of life: How fears of negative and positive evaluation relate to specific domains of life satisfaction. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, E.A.; Garfin, D.R.; Lubens, P.; Silver, R.C. Media exposure to collective trauma, mental health, and functioning: Does it matter what you see? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 8, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.; Veksler, A. Stop talking about it already! Co-ruminating and social media focused on COVID-19 was associated with heightened state anxiety, depressive symptoms, and perceived changes in health anxiety during Spring 2020. BMC Psychol. 2022, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrean, A.; Păsărelu, C.-R. Impact of Social Media on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. In New Developments in Anxiety Disorders; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, L.; Liu, D.; Luo, J. Explicating user negative behavior toward social media: An exploratory examination based on stressor–strain–outcome model. Cogn. Technol. Work 2022, 24, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.H.; Rodebaugh, T.L.; Zyphur, M.J.; Gleeson, J.F. Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren-Yagoda, R.; Melamud-Ganani, I.; Aderka, I.M. All by myself: Loneliness in social anxiety disorder. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2022, 131, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.J.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.H.; Pan, H.F.; Su, P.Y. Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, P.; Duque, V.; Luzio-Vaz, A.; Pereira, A. Anxiety impact during COVID-19: A systematic review. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindred, R.; Bates, G.W.; McBride, N.L. Long-term outcomes of cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J. Anxiety Disord. 2022, 92, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.N.; Bilek, E.; Tomlinson, R.C.; Becker-Haimes, E.M. Treating Social Anxiety in an Era of Social Distancing: Adapting Exposure Therapy for Youth During COVID-19. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021, 28, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peros, O.; Webb, L.; Fox, S.; Bernstein, A.; Hoffman, L. Conducting Exposure-Based Groups via Telehealth for Adolescents and Young Adults with Social Anxiety Disorder. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021, 28, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molino, A.T.C.; Kriegshauser, K.D.; McNamara Thornblade, D. Transitioning from In-Person to Telehealth Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study in Flexibility in an Adverse Context. Clin. Case Stud. 2022, 21, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, A.S.; Gros, D.F.; McCabe, R.E.; Antony, M.M. Clinical predictors of diagnostic status in individuals with social anxiety disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, A.; Ertekin, E.; Ertekin, B.A.; Binbay, Z.; Yüksel, Ç.; Deveci, E.; Tükel, R. Relationship between atypical depression and social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 225, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Cristea, I.A.; Weitz, E.; Gentili, C.; Berking, M. The effects of cognitive and behavioural therapies for anxiety disorders on depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 3451–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sahni, P.S.; Sharma, U.S.; Kumar, J.; Garg, R. Effect of Yoga on the Stress, Anxiety, and Depression of COVID-19-Positive Patients: A Quasi-Randomized Controlled Study. Int. J. Yoga Therap. 2022, 32, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, R.; Ray, S.; Cohen, T. Mindfulness as a way to cope with COVID-19-related stress and anxiety. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2020, 21, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.L.; Schülke, R.; Vatansever, D.; Xi, D.; Yan, J.; Zhao, H.; Xie, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, M.Y.; Sahakian, B.J.; et al. Mindfulness practice for protecting mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, D.; Lin, R.; Wang, Z.; Pan, L. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety and sleep quality in patients with COVID-19. Complement Clin. Pr. 2020, 39, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, A.S.; Heimberg, R.G. Social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Country | Sample Size | Sample Characteristics (SD in Parentheses) | Population Type | Design and Date of Data Collection (dd/mm/yyyy) | Relevant Measures | Qualsyst Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arad et al. [44] | Israel | n = 99 | Mean age (treatment): 22.62 (2.36) Mean age (control): 21.57 (1.90) Gender: 85% female | University students (>50 LSAS) | Natural experiment T1: September 2019 to December 2019 T2: January 2020 to April 2020 | LSAS-SR, PHQ-9 | 0.95 (strong) |

| Bendau et al. [45] | Germany | n = 307 | Mean age: 39.64 (11.7) Gender: 71.2% female | Clinical (self-diagnosed) | Longitudinal T1: 27 March 2020 to 6 April 2020 T2: 24 April 2020 to 4 May 2020 T3: 15 May 2020 to 25 May 2020 T4: 5 June 2020 to 15 June 2020 | C-19-A, PHQ-4 | 0.95 (strong) |

| Blasco-Belled et al. [46] | Spain | n = 541 | Mean age: 38.82 (15.97) Gender: 65.8% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from 12 March 2020 to 15 March 2020 | LSAS-SR, PWI, SPANE | 0.91 (strong) |

| Buckner et al. [47] | USA | n = 120 | Mean age: 19.8 (1.6) Gender: unspecified | Community | Longitudinal T1: 16 February 2020 to 13 March 2020 T2: 13 April 2020 to 15 May 2020 | DASS-21, SIAS, Worry Index | 0.91 (strong) |

| Carlton et al. [48] | USA | n = 84 | Mean age: 19.5 (1.47) Gender: 73.8% female | Clinical | Repeated cross-sectional T1: January 2021 to March 2021 T2: 1 month after T1 | ADIS-5, DASS-21, FIVE, RSQ, SAFE | 0.82 (strong) |

| Charmaraman et al. [49] | USA | n = 586 | Mean age: 12.53 (1.18) Gender: 53% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: September 2019 to November 2019 T2: October 2020 to December 2020 | CESDR-10, COVID-19-Related Grief Scale, PRIUSS, SAS-A | 0.95 (strong) |

| Czorniej et al. [50] | Poland | n = 255 | Mean age: 24.30 (1.69) Gender: 53.7% female | Healthcare Students | Cross-sectional Data collected from May 2021 to May 2022 | LSAS, STAI | 0.85 (strong) |

| Eskiyurt & Akaca [51] | Turkey | n = 670 | Mean age: 20.77 (2.77) Gender: 82% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from February 2020 to February 2021 | B-FNE, LSAS | 0.91 (strong) |

| Falco et al. [52] | Spain | n = 439 | Mean age: 36.64 (13.37) Gender: 73.1% female | University Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from March 2020 to May 2020 | ESTAD Anxiety and depression disorders symptoms scale, F-COVID-19, Impact of event scale-revised | 0.86 (strong) |

| Fawwaz et al. [53] | Malaysia | n = 158 | Mean age: 21.77 (1.54) Gender: 56.3% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from January 2021 to February 2021 | MTOQ, UMS, SPIN | 0.73 (good) |

| Hawes et al. [54] | USA | n = 451 | Mean age: 17.49 (1.42) Gender: 65.4% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: Pre-pandemic (unspecified) T2: 27 March 2020 to 15 May 2020 | CDI, SCARED | 0.91 (strong) |

| Ho & Moscovitch [55] | USA | n = 488 | Median age: 25–39 (N/A) Gender: 48% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from May 2020 | BFNE, CAS, CSS, SDSa, SIAS, TILS | 0.86 (strong) |

| Huang et al. [56] | China | n = 501 | Mean age: 24.31 (7.83) Gender: 63.9% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from March 2020 | IPCS, LSAS-SR | 0.91 (strong) |

| Itani et al. [57] | Lebanon | n = 178 | Median age: 16 years old Gender: 59.0% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from August 2020 to September 2020 | LSAS-CA | 0.73 (good) |

| Ju et al. [58] | China | n = 199 | Mean age: 42.72 (17.53) Gender: 53.3% female | Discharged COVID-19 patients | Cross-sectional Data collected from July 2020 to September 2020 | Self-Stigma Scale, Self- consciousness Scale | 0.77 (good) |

| Juvonen et al. [59] | USA | n = 1557 | Mean age: 22.5 (0.75) Gender: 62% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: Pre-pandemic (2017–2019) T2: March 2021 to June 2021 | CES-D, GAD-7, SAS-A | 0.95 (strong) |

| Krämer et al. [60] | Germany | n = 190 | Mean age: 44.2 (14.18) Gender: 47% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: 6 April 2020 T2: 29 April 2020 T3: 20 May 2020 T4: 10 June 2020 | BFI-2, PHQ-4, SIAS-6, SOEP, Unified Motive Scale | 0.91 (strong) |

| Langhammer et al. [61] | Germany | n = 47 | Mean age: 37.3 (10.78) Gender: 60% female | Clinical outpatient | Cross-sectional Data collected from July 2020 | BDI-II, HAMA-A, PAS, PHQ-9, SMSP | 0.82 (strong) |

| Li [62] | China | n = 600 | Median age: 20 (N/A) Gender: 46% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from March 2020 | SIAS | 0.68 (adequate) |

| Liang et al. [63] | China | n = 3137 | Mean age: N/A Gender: 78.58% female | University students | Cross-sectional Data collected from February 2020 | SAD, SAS, SDSb | 0.82 (strong) |

| Lim et al. [64] | Australia | n = 1562 | Mean age = 48.8 Gender: 84.2% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: March 2020 T2: 6–8 weeks after T1 T3: 6–8 weeks after T2 | Mini-SPIN, PHQ-8, UCLA Loneliness Scale | 1.0 (strong) |

| Ma [65] | USA | n = 23 | Mean age: 21.3 (N/A) Gender: 78.3% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from September 2020 to December 2020 | CD-RISC-10, GAD-7, SM-SAD | 0.41 (limited) |

| McLeish et al. [66] | USA | n = 934 | Mean age: 20.4 (3.59) Gender: 72.4% female | University students | Repeated cross-sectional T1: March 2020 to May 2020 T2: September 2020 to December 2020 T3: January 2021 to April 20201 | OASIS, ODSIS, PSWQ-3, SIAS-6, SPS-6, SSASI | 0.73 (good) |

| Morales et al. [67] | USA | n = 164 | Mean age: 16.16 (0.61) Gender: N/A | Community | Longitudinal T1: March 2017 to August 2019 T2: April 2020 to May 2020 T3: June 2020 to July 2020 T4: August 2020 to September 2020 | SCARED, CASPE, GAD-7, K-SADS, PSS-10 | 0.95 (strong) |

| Moran et al. [68] | USA | n = 32 | Mean age: 27.9 (4.52) Gender: 90.6% female | Domestic Violence Survivors | Cross-sectional Data collected from January 2021 to March 2021 | ABI, IDAS, MAC-RF, MSPSS | 0.65 (adequate) |

| Pang [69] | China | n = 566 | Median age: 21–23 (N/A) Gender: 58.8% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from April 2020 | 0.82 (strong) | |

| Quittkat et al. [70] | Germany | n = 86 | Mean age: 33.41 (11.45) Gender: 73% female | Clinical (self-diagnosed) | Cross-sectional Data collected from 2 April 2020 to 6 May 2020 | PHQ-9, SIAS, SPS | 0.95 (strong) |

| Samantaray et al. [71] | India | n = 65 | Mean age: 21.77 (2.67) Gender 53.8% female | Clinical | Cross-sectional Data collection unspecified. | F-COVID-19, SPIN | 0.83 (strong) |

| Tekin [72] | Turkey | n = 118 | Mean age: 13.2 (2.1) Gender 65% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from March 2021 to April 2021 | ARI-P, RCADS-P, PedsQL, Turgay-DSM-IV-S | 0.77 (good) |

| Terin et al. [73] | Turkey | n = 199 | Mean age: 14.48 (2.15) Gender: 74.6% female | Hospital patients | Cross-sectional Data collected from October 2021 to January 2022 | CAS, CASI, RCADS-CV | 0.91 (strong) |

| Thompson et al. [42] | USA | n = 204 | Mean age: 30.4 (11.2) Gender: 83.2% female | Community | Cross-sectional Data collected from September 2020 | LSNS-6, SPS, UCLA Loneliness scale | 0.55 (adequate) |

| Yurteri & Sarigedik [74] | Turkey | n = 60 | Mean age: 10.22 (N/A) Gender: 46.7% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: Pre-pandemic (unspecified) T2: Post-Pandemic (unspecified) | CDI, SCARED | 0.86 (strong) |

| Zhu et al. [43] | China | n = 1393 | Mean age: 13.04 (0.86) Gender 53.1% female | Community | Longitudinal T1: September 2019 T2: June 2020 | GAD-7, PHQ-9, MSPSS, MDASS, SAS, SCS, STAI, SWLS | 0.95 (strong) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kindred, R.; Bates, G.W. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032362

Kindred R, Bates GW. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032362

Chicago/Turabian StyleKindred, Reuben, and Glen W. Bates. 2023. "The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032362

APA StyleKindred, R., & Bates, G. W. (2023). The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032362