A Community-Based, Participatory, Multi-Component Intervention Increased Sales of Healthy Foods in Local Supermarkets—The Health and Local Community Project (SoL)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Intervention

2.2. Data Collection Methods

2.3. Statistical Analyses

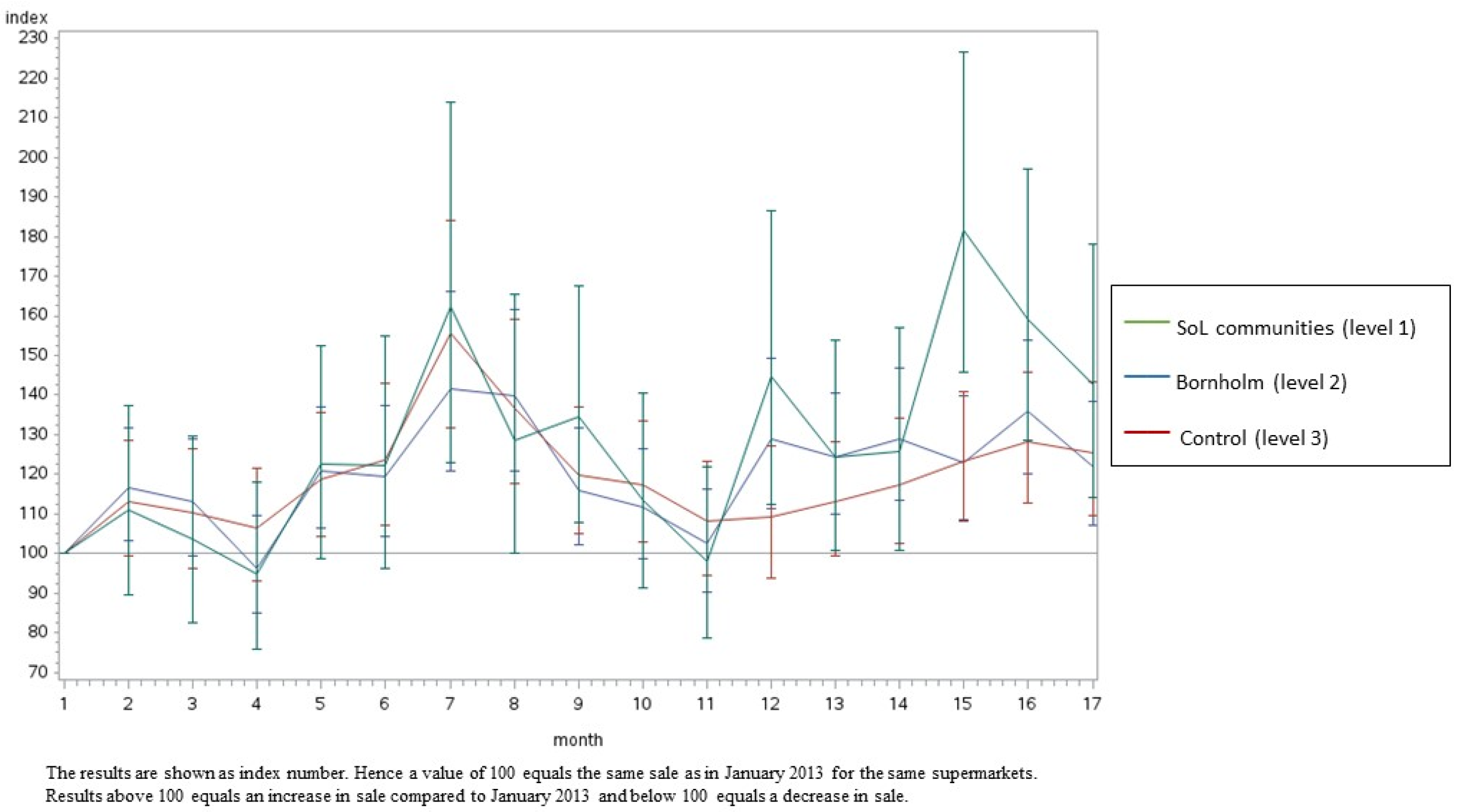

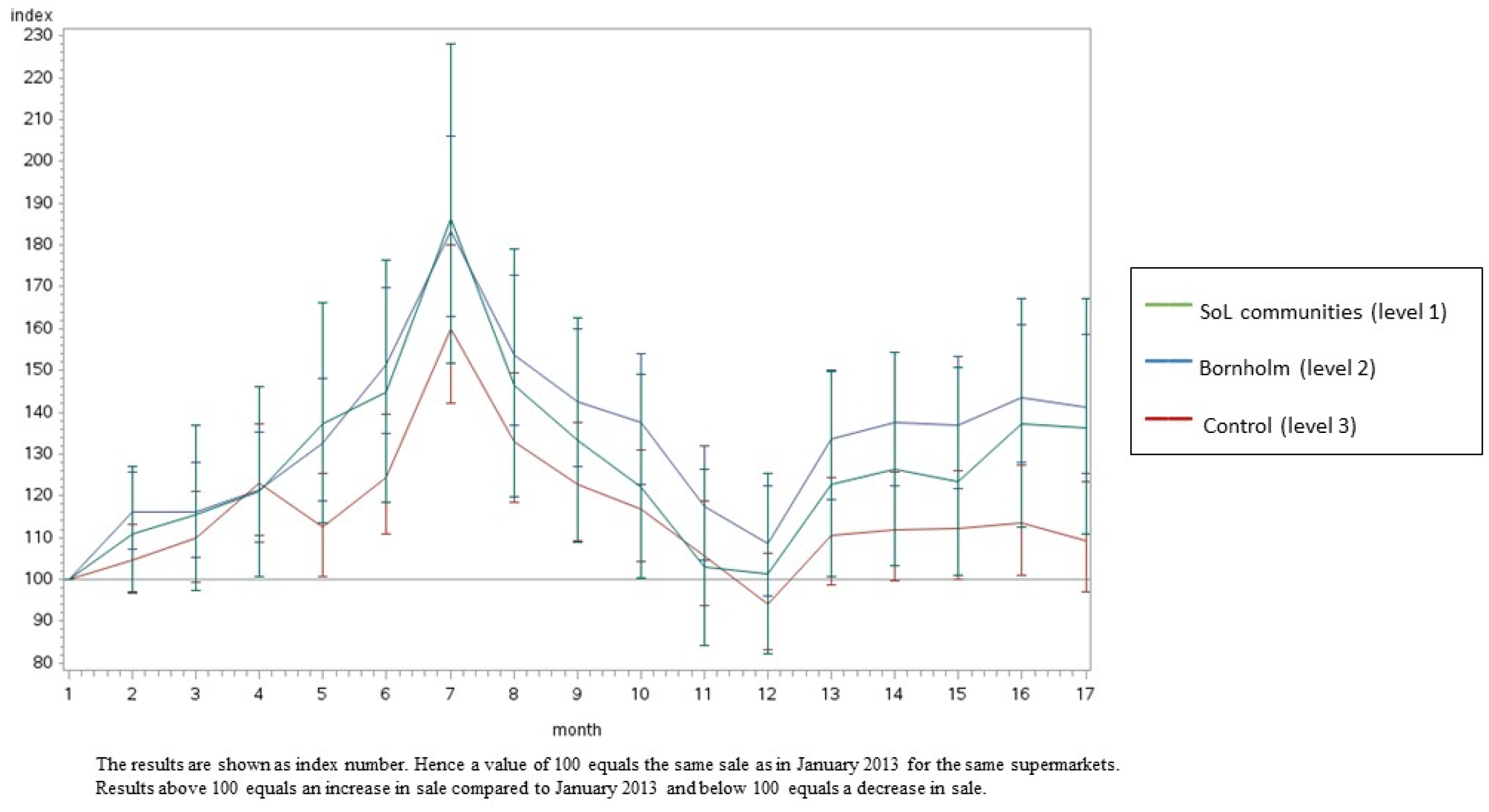

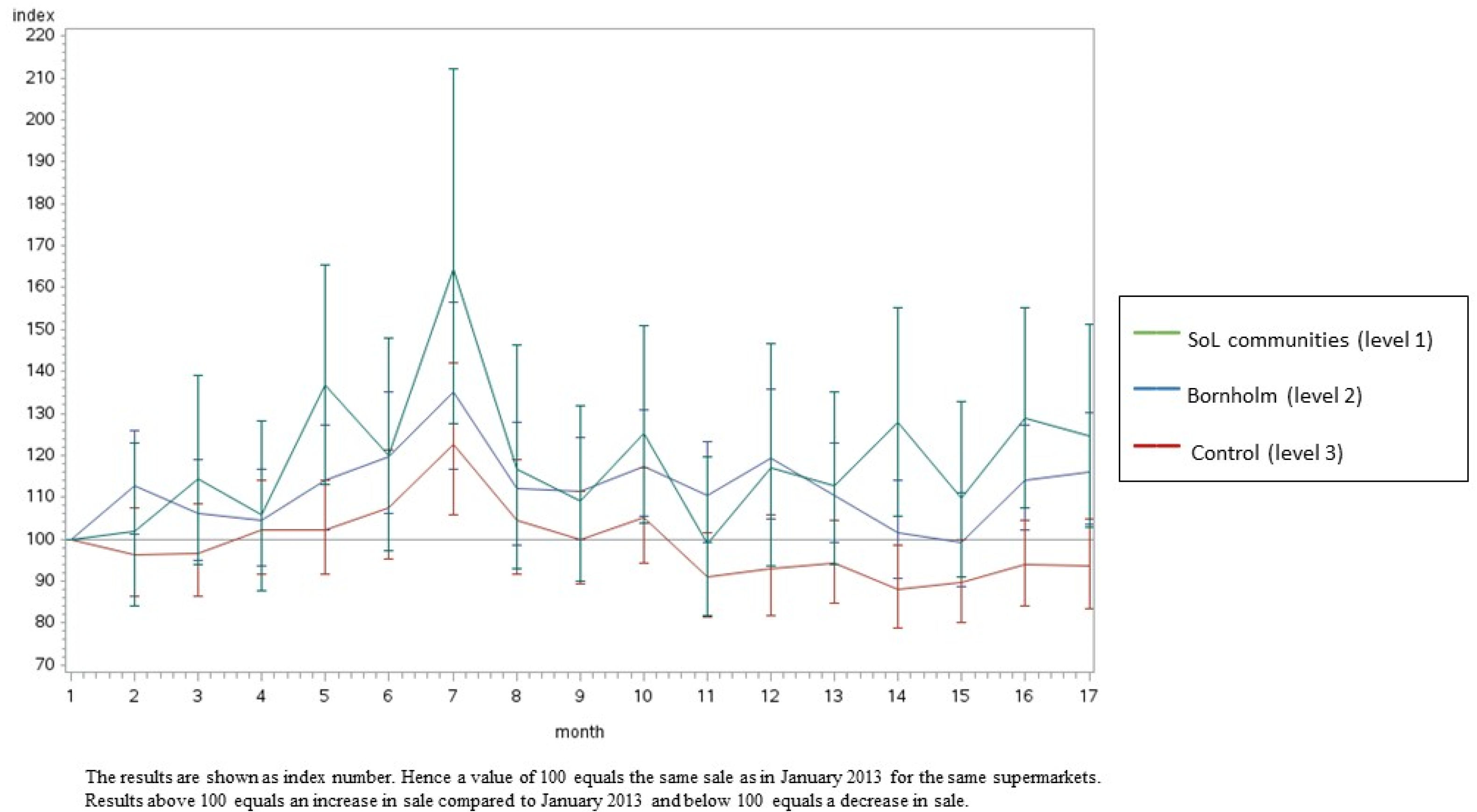

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, L.L.; Anzman, S.L. Learning to eat in an obesogenic environment: A developmental systems perspective on childhood obesity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, N.; Lytle, L.A.; Klepp, K.I. Stability in consumption of fruit, vegetables, and sugary foods in a cohort from age 14 to age 21. Prev. Med. 2001, 33, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkila, V.; Rasanen, L.; Raitakari, O.T.; Pietinen, P.; Viikari, J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, A.N.; Christensen, T.; Matthiessen, J.; Knudsen, V.K.; Sørensen, M.R.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.P.; Hinsch, H.-J.; Ygil, K.H.; Kørup, K.; Saxholt, E. Danskernes kostvaner 2011–2013. In Hovedresultater (Dietary Habits in Denmark 2011–2013. Main Results), 1st ed.; National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Nordic Council of Ministers. Nordic nutrition recommendations 2012. In Integrating Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5th ed.; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Danish Veterinary and Food Administration. The Official Dietary Guidelines. 2021. Available online: www.altomkost.dk (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Waterlander, W.E.; Pinzon, A.L.; Verhoef, A.; Hertog, K.d.; Altenburg, T.; Dijkstra, C.; Halberstadt, J.; Hermans, R.; Renders, C.; Seidell, J.; et al. Understanding obesity-related behaviors in youth from a systems dynamics perspective: The use of causal loop diagrams. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, S.; Taylor, F.; Ward, K.; Burke, M.; Smith, G.D. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 19, CD001561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beauchamp, A.; Backholer, K.; Magliano, D.; Peeters, A. The effect of obesity prevention interventions according to socioeconomic position: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Promoting Healthy Weight in Children, Young People and Families: A Resource to Support Local Authorities; PHE Publications: London, UK, 2018; gateway number: 2018530. [Google Scholar]

- Allender, S.; Orellana, L.; Crooks, N.; Bolton, K.A.; Fraser, P.; Dwight Brown, A.; Le, H.; Lowe, J.; Haye, K.; Millar, L.; et al. Four-Year Behavioral, Health-Related Quality of Life, and BMI Outcomes from a Cluster Randomized Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for Childhood Obesity. Obesity 2021, 29, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, M.; Hammond, R.A.; Heuberger, B.; Mack-Crane, A.; Purcell, R.; Economos, C.; Swinburn, B.; Allender, S.; Nichols, M. Activating a community: An agent-based model of Romp & Chomp, a whole-of-community childhood obesity intervention. Obesity 2019, 27, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Verjans-Janssen, S.R.B.; van de Kolk, I.; Van Kann, D.H.H.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Gerards, S.M.P.L. Effectiveness of school-based physical activity and nutrition interventions with direct parental involvement on children’s BMI and energy balance-related behaviors—A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e020456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.C.; Buchan, D.S.; Baker, J.S.; Wyatt, F.B.; Bocalini, D.S.; Kilgore, L. A Systematised Review of Primary School Whole Class Child Obesity Interventions: Effectiveness, Characteristics, and Strategies. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 4902714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerrato-Carretero, P.; Pedrera-Zamorano, J.; López-Espuela, F.; Puerto-Parejo, L.M.; Sánchez-Fernández, A.; Canal-Macías, M.L.; Moran, J.M.; Lavado-García, J.M. Long-Term Dietary and Physical Activity Interventions in the School Setting and Their Effects on BMI in Children Aged 6-12 Years: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Healthcare 2021, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, A.; Radley, D.; Jones, R.; Gately, P.; Nobles, J.; Dijk, M.V.; Blackshaw, J.; Montel, S.; Sahota, P. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodgren, G.M.; Helleve, A.; Lobstein, T.; Rutter, H.; Klepp, K.I. Primary prevention of overweight and obesity in adolescents: An overview of systematic reviews. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhoff, M.; Joore, M.; Ferreira, I. The effects of school-based lifestyle interventions on body mass index and blood pressure: A multivariate multilevel meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2016, 17, 1131–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nigg, C.R.; Anwar, M.M.; Braun, K.; Mercado, J.; Kainoa Fialkowski, M.; Ropeti Areta, A.A.; Belyeu-Camacho, T.; Bersamin, A.; Guerrero, R.L.; Castro, R.; et al. A Review of Promising Multicomponent Environmental Child Obesity Prevention Intervention Strategies by the Children’s Healthy Living Program. J. Environ. Health 2016, 79, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Milestones in Health Promotion, Statements from Global Conferences. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, Canada, 17–21 November 1986; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, P.; Toft, U.; Reinbach, H.C.; Clausen, L.T.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Poulsen, K.; Jensen, B.B. Revitalizing the setting approach-super-settings for sustainable impact in community health promotion. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Toft, U.; Bloch, P.; Reinbach, H.C.; Winkler, L.L.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Jensen, B.B.; Glumer, C. Project SoL—A Community-Based, Multi-Component Health Promotion Intervention to Improve Eating Habits and Physical Activity among Danish Families with Young Children. Part 1: Intervention Development and Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mikkelsen, B.E.; Bloch, P.; Reinbach, H.C.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Lawaetz Winkler, L.; Toft, U.; Glümer, C.; Jensen, B.B.; Aagaard-Hansen, J. Project SoL—A Community-Based, Multi-Component Health Promotion Intervention to Improve Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Practices among Danish Families with Young Children Part 2: Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poulsen, I. Hvordan Har Du Det? 2010, Sundhedsprofil for Region Sjælland og Kommuner (How Are You? 2010, Health Profiles of Region Zealand and Municipalities); Region Sjælland: Sorø, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glümer, C. Danish National Health Profile Study; Research Centre for Prevention and Health, Capital Region: Glostrup, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jungk, R.; Mullert, N.R. Future Workshops: How to Create Desirable Futures; Institute for Social Inventions: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, L.T.; Schmidt, C.; Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Reinbach, H.C.; Toft, U.; Bloch, P. Children as visionary change agents in Danish school health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 34, e18–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, S.N.; Segal, J.; Wu, Y.; Wilson, R.; Wang, Y. Systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics 2013, 132, e201–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, T.; Moore, T.H.; Hooper, L.; Gao, Y.; Zayegh, A.; Ijaz, S.; Elwenspoek, M.; Foxen, S.C.; Magee, L.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 7, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewart-Pierce, E.; Ruiz, M.J.M.; Gittelsohn, J. “Whole-of-Community” Obesity Prevention: A Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Multilevel, Multicomponent Interventions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Silva-Sanigorski, A.M.; Bell, A.C.; Kremer, P.; Nichols, M.; Crellin, M.; Smith, M.; Sharp, S.; De Groot, F.; Carpenter, L.; Boak, R.; et al. Reducing obesity in early childhood: Results from Romp & Chomp, an Australian community-wide intervention program. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanigorski, A.M.; Bell, A.C.; Kremer, P.J.; Cuttler, R.; Swinburn, B.A. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in children through community capacity-building: Results of a quasi-experimental intervention program, Be Active Eat Well. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Economos, C.D.; Hyatt, R.R.; Must, A.; Goldberg, J.P.; Kuder, J.; Naumova, E.N.; Collins, J.J.; Nelson, M.E. Shape Up Somerville two-year results: A community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomitz, V.R.; McGowan, R.J.; Wendel, J.M.; Williams, S.A.; Cabral, H.J.; King, S.E.; Olcott, D.B.; Cappello, M.; Breen, S.; Hacker, K.A. Healthy Living Cambridge Kids: A community-based participatory effort to promote healthy weight and fitness. Obesity 2010, 18 (Suppl. S1), S45–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch-Andersen, T.; Eriksson, F.; Bloch, P.; Glümer, C.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Toft, U. The Danish SoL Project: Effects of a Multi-Component Community-Based Health Promotion Intervention on Prevention of Overweight among 3–8-Year-Old Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minary, L.; Trompette, J.; Kivits, J.; Cambon, L.; Tarquinio, C.; Alla, F. Which design to evaluate complex interventions? Toward a methodological framework through a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Method. 2019, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Characteristic | Unit | Bornholm | Odsherred |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population and area | Population | 1000 | 41 | 32 |

| Area, square km | Km2 | 588 | 355 | |

| Health status | Overweight, BMI > 25 | % | 50 | 53 |

| Diabetes | % | 6.5 | 5.7 | |

| High blood pressure | % | 16 | 23 | |

| Health behaviour | Citizens with very unhealthy dietary habits | % | 14 | 16 |

| Citizens with < 30 min/day MVPA * | % | 36 | 41 | |

| Citizens with self-perceived poor health | % | 18 | 21 | |

| Socio-economic status (SES) | Unemployed | % | 26 | 28 |

| No vocational education | % | 19 | 18 |

| Multi-Component Intervention Vs. No Intervention (Control) Index | Multi-Component Intervention vs. Mass Media Intervention Only Index | Mass MEDIA intervention Only vs. No Intervention (Control) Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | p-Value | Estimate | p-Value | Estimate | p-Value | |

| Fish, total | 1.2950 | 0.0028 | 1.1328 | 0.1565 | 1.1432 | 0.0659 |

| Fish, canned | 1.3072 | 0.0253 | 1.3042 | 0.0249 | 1.0023 | 0.9788 |

| Vegetables, total | 1.220 | 0.0595 | 1.0449 | 0.6761 | 1.1675 | 0.0383 |

| Vegetables, fresh | 1.1180 | 0.2518 | 0.9353 | 0.4775 | 1.1976 | 0.0097 |

| Fruit, fresh | 1.1135 | 0.4514 | 1.0448 | 0.7595 | 1.0658 | 0.5332 |

| Fruit, dried | 1.6004 | 0.0620 | 1.057 | 0.8225 | 1.5138 | 0.0217 |

| Oatmeal | 1.3102 | 0.0028 | 1.1041 | 0.2715 | 1.1867 | 0.0080 |

| Wholegrain pasta | 1.143 | 0.4727 | 0.7227 | 0.0834 | 1.5815 | 0.0007 |

| Sweets | 0.9876 | 0.8934 | 1.0116 | 0.9009 | 0.9762 | 0.7192 |

| Sugary beverages | 1.0620 | 0.5039 | 1.0012 | 0.9891 | 1.0608 | 0.3599 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toft, U.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Bloch, P.; Reinbach, H.C.; Jensen, B.B.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Aagaard-Hansen, J.; Glümer, C. A Community-Based, Participatory, Multi-Component Intervention Increased Sales of Healthy Foods in Local Supermarkets—The Health and Local Community Project (SoL). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032478

Toft U, Buch-Andersen T, Bloch P, Reinbach HC, Jensen BB, Mikkelsen BE, Aagaard-Hansen J, Glümer C. A Community-Based, Participatory, Multi-Component Intervention Increased Sales of Healthy Foods in Local Supermarkets—The Health and Local Community Project (SoL). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032478

Chicago/Turabian StyleToft, Ulla, Tine Buch-Andersen, Paul Bloch, Helene Christine Reinbach, Bjarne Bruun Jensen, Bent Egberg Mikkelsen, Jens Aagaard-Hansen, and Charlotte Glümer. 2023. "A Community-Based, Participatory, Multi-Component Intervention Increased Sales of Healthy Foods in Local Supermarkets—The Health and Local Community Project (SoL)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032478