Grit but Not Help-Seeking Was Associated with Food Insecurity among Low Income, At-Risk Rural Veterans

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

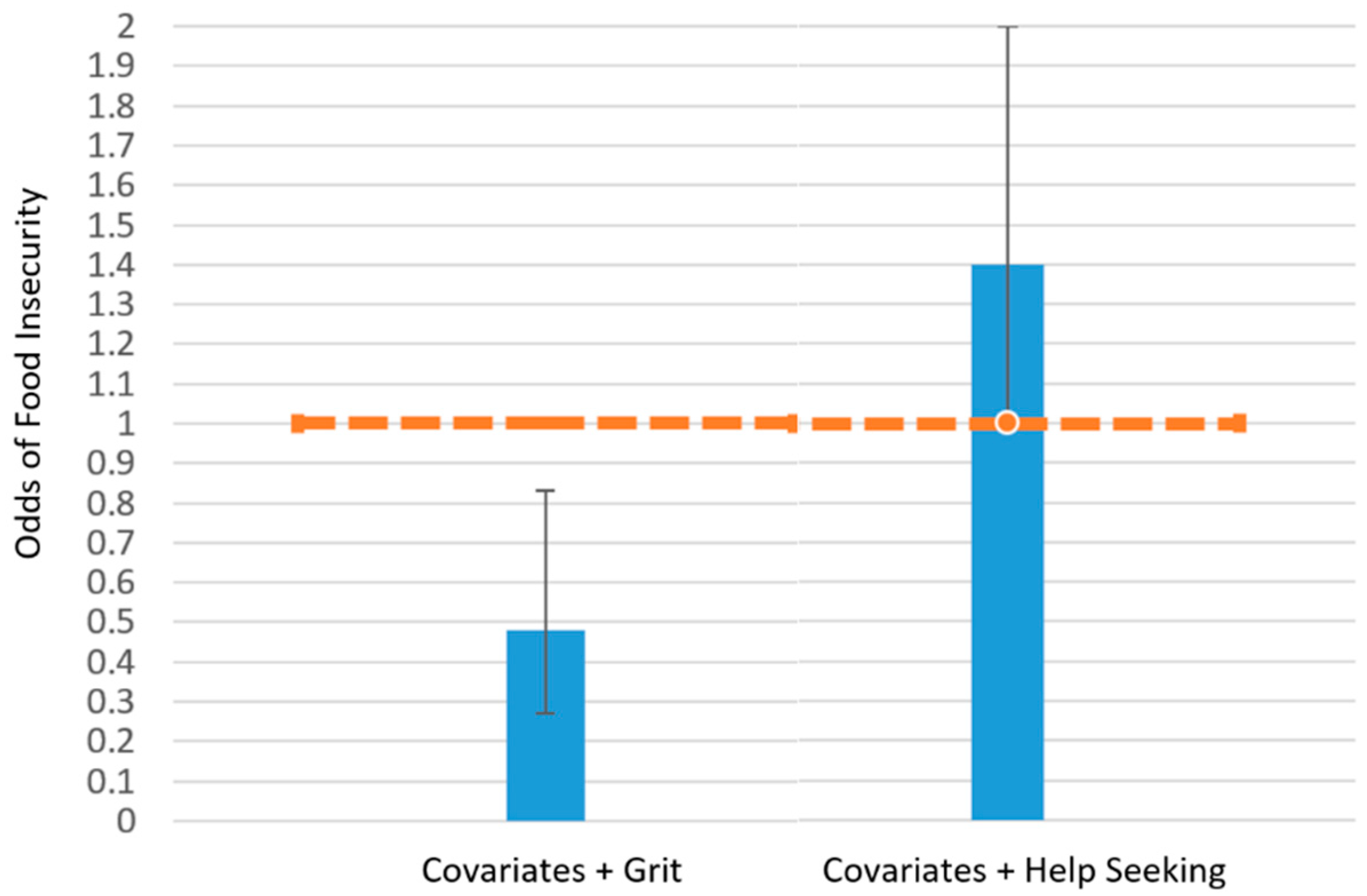

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rural Veterans—Office of Rural Health. Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Weeda, E.R.; Bishu, K.G.; Ward, R.; Axon, R.N.; Taber, D.J.; Gebregziabher, M. Joint effect of race/ethnicity or location of residence and sex on low density lipoprotein-cholesterol among veterans with type 2 diabetes: A 10-year retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.P.; Strom, J.L.; Egede, L.E. Disparities in diabetes self-management and quality of care in rural versus urban veterans. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2011, 25, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, W.B.; Wallace, A.E.; West, A.N.; Heady, H.R.; Hawthorne, K. Research on rural veterans: An analysis of the literature. J. Rural Health 2008, 24, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health. Addressing the Health Care Needs of Rural Veterans a Guide for State Offices of Rural Health. Available online: https://www.nosorh.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/NOSORH-Rural-Veterans-Health-Guidenhmedits-21.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2018. ERR-270, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2019. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/94849/err-270.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Widome, R.; Jensen, A.; Bangerter, A.; Fu, S.S. Food insecurity among veterans of the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, E.A.; McGinnis, K.A.; Goulet, J.; Bryant, K.; Gibert, C.; Leaf, D.A.; Mattocks, K.; Fiellin, L.E.; Vogenthaler, N.; Justice, A.C.; et al. Food insecurity and health: Data from the veterans aging cohort study. Public Health Rep. 2015, 130, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- US Census Bureau. Those Who Served: America’s Veterans from World War II to the War on Terror. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/acs-43.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Food Insecurity|Healthy People 2020. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/food-insecurity (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Feeding America. What Is Food Insecurity? Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purtell, K.M.; Gershoff, E.T.; Aber, J.L. Low income families’ utilization of the Federal “Safety Net”: Individual and state-level predictors of TANF and Food Stamp receipt. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Characteristics of Rural Veterans: 2010 Data from the American Community Survey. Available online: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Rural_Veterans_ACS2010_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Porcari, C.; Koch, E.I.; Rauch, S.A.M.; Hoodin, F.; Ellison, G.; McSweeney, L. Predictors of help-seeking intentions in operation enduring freedom and operation Iraqi freedom veterans and service members. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, e1640–e1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheney, A.M.; Koenig, C.J.; Miller, C.J.; Zamora, K.; Wright, P.; Stanley, R.; Fortney, J.; Burgess, J.F.; Pyne, J.M. Veteran-centered barriers to VA mental healthcare services use. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veterans Benefits 2020: Most Underused State Benefit. Available online: https://news.va.gov/76440/veterans-benefits-2020-underused-state-benefit/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Karabenick, S.A. Seeking help in large college classes: A person-centered approach. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 28, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credé, M.; Tynan, M.C.; Harms, P.D. Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 113, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 413–426. [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian, T.; Jaycox, L.H.; RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research. Invisible Wounds of War Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. 2008. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG720.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Stecker, T.; Fortney, J.C.; Sherbourne, C.D. An Intervention to increase Mental Health Treatment Engagement among OIF veterans: A pilot trial. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McFall, M.; Malte, C.; Fontana, A.; Rosenheck, R.A. Effects of an outreach intervention on use of mental health services by veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D. Development and validation of the short Grit Scale (Grit-S). J. Pers. Assess. 2009, 91, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, C.J.; Schierer, M.; Ellison, B.; Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Gundersen, C.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Grit is associated with food security among US parents and adolescents. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Nettle, D. Time perspective, personality and smoking, body mass, and physical activity: An empirical study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paunesku, D.; Walton, G.M.; Romero, C.; Smith, E.N.; Yeager, D.S.; Dweck, C.S. Mind-Set Interventions Are a Scalable Treatment for Academic Underachievement. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanhove, A.J.; Herian, M.N.; Perez, A.L.U.; Harms, P.D.; Lester, P.B. Can resilience be developed at work? A meta-analytic review of resilience-building programme effectiveness. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 278–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, C.A.; Beyl, R.A.; Martin, C.K.; Broyles, S.T.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Psychological mechanisms associated with food security status and BMI in adults: A mixed methods study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2501–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindow, J.C.; Hughes, J.L.; South, C.; Minhajuddin, A.; Gutierrez, L.; Bannister, E.; Trivedi, M.H.; Byerly, M.J. The Youth Aware of Mental Health Intervention: Impact on Help Seeking, Mental Health Knowledge, and Stigma in U.S. Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiljer, D.; Shi, J.; Lo, B.; Sanches, M.; Hollenberg, E.; Johnson, A.; Abi-Jaoudé, A.; Chaim, G.; Cleverley, K.; Henderson, J.; et al. Effects of a Mobile and Web App (Thought Spot) on Mental Health Help-Seeking among College and University Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Agriculture Economics Research Service. Rural Classifications. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- United States Census Beureau. Population and Housing Unit Estimates Datasets. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Wright, B.; MacDermid Wadsworth, S.; Wellnitz, A.; Eicher-Miller, H. Reaching rural veterans: A new mechanism to connect rural, low-income US Veterans with resources and improve food security. J. Public Health 2019, 41, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smid, W.J.; Kamphuis, J.H.; Wever, E.C.; Van Beek, D.J. A comparison of the predictive properties of nine sex offender risk assessment instruments. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, M.C. Handling Item-Level Missing Data: Simpler Is Just as Good. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 41, 568–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.J.; Deane, F.P.; Ciarrochi, J.V.; Rickwood, D. Measuring help seeking intentions: Properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Can. J. Couns. 2005, 39, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. Alexandria VA. 2000. Available online: https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/38369/PDF (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Ma, C.; Ho, S.K.M.; Singh, S.; Choi, M.Y. Gender Disparities in Food Security, Dietary Intake, and Nutritional Health in the United States. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Equitable Care for Elders. Food Insecurity among Older Adults. 2019. Available online: https://ece.hsdm.harvard.edu/files/ece/files/food_insecurity_issue_brief_-_december_2019.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020. ERR-298, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Smith, M. Fact Sheet Gender and Food Insecurity: The Burden on Poor Women. Available online: https://socwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Fact-Sheet-Gender-and-Food-Insec.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Profile of Veterans: 2017. Available online: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Kamdar, N.; Lester, H.F.; Daundasekara, S.S.; Greer, A.E.; Hundt, N.E.; Utech, A.; Hernandez, D.C. Food insecurity: Comparing odds between working-age veterans and nonveterans with children. Nurs. Outlook. 2021, 69, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, T.P.; Roberts, C.B.; Johnson, E.E. Screening for Food Insecurity in Six Veterans Administration Clinics for the Homeless, June-December 2015. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2017, 14, E04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, A.J.; Dosa, D.M.; Rudolph, J.L.; Halladay, C.W.; Heisler, M.; Thomas, K.S. Risk factors for Veteran food insecurity: Findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stretesky, P.; Defeyter, G. Food Insecurity among UK Veterans. Armed Forces Soc. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pooler, J.A.; Srinivasan, M.; Miller, Z.; Mian, P. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Food Insecurity Among Low-Income US Military Veterans. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, A.S.; Heflin, C.M. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Use Among Active-Duty Military Personnel, Veterans, and Reservists. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2015, 34, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illinois Department of Human Services. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—SNAP. Available online: https://www.dhs.state.il.us/page.aspx?item=30357 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Zhao, C.; Guo, J. Are Veterans Happy? Long-term Military Service and the Life Satisfaction of Elderly Individuals in China. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 477–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, N.P.; Horning, M.L.; Geraci, J.C.; Uzdavines, A.W.; Helmer, D.A.; Hundt, N.E. Risk for depression and suicidal ideation among food insecure US veterans: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 2175–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brostow, D.P.; Smith, A.A.; Bahraini, N.H.; Besterman-Dahan, K.; Forster, J.E.; Brenner, L.A. Food Insecurity and Food Worries During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Point-In-Time Study of Injured United States Veterans. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2022, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widome, R.; Jensen, A.; Fu, S.S. Socioeconomic disparities in sleep duration among veterans of the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e70–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, J.; Poirier, A.; Pound, T.; VanTil, L. Well-Being of Canadian Regular Force Veterans, Findings from LASS 2019 Survey. Charlottetown PE: Veterans Affairs Canada. Research Directorate Technical Report. 9 October 2020. Available online: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/about-vac/research/research-directorate/publications/reports/lass-well-being-2020 (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- O’Toole, B.I.; Catts, S.V.; Outram, S.; Pierse, K.R.; Cockburn, J. The physical and mental health of Australian Vietnam veterans 3 decades after the war and its relation to military service, combat, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, J.M.; VanTil, L.D.; Zamorski, M.A.; Garber, B.; Dursun, S.; Fikretoglu, D.; Ross, D.; Richardson, J.D.; Sareen, J.; Sudom, K.; et al. Mental health of Canadian Armed Forces Veterans: Review of population studies. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. 2016, 2, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanTil, L.D.; MacLean, M.; Sweet, J.; McKinnon, K. Understanding future needs of Canadian veterans. Health Rep. 2018, 29, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, D.; Borowski, S.C.; Godier-McBard, L.R.; Fossey, M.J.; Copeland, L.A.; Perkins, D.F.; Finley, E.P. Changes in the health and broader well-being of US veterans in the first three years after leaving military service: Overall trends and group differences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 294, 114702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, C.; Morello, A.; Venning, A.; Redpath, P.; Lawn, S. The health and wellbeing needs of veterans: A rapid review. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanch, S.; Barkus, E. Schizotypy and help-seeking for anxiety. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1433–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, E.G.; VanDenKerkhof, E.G.; Johnson, A.; Gilron, I. Help-seeking behavior among community-dwelling adults with chronic pain. Can. J. Pain. 2019, 3, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher-miller, H.A.; Rivera, R.L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Maulding, M.K.; Abbott, A.R. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education Improves Food Security Independent of Food Assistance and Program Characteristics. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | % 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–44 years | 16 | 9.0 | |

| 45–64 years | 46 | 26.0 | |

| ≥65 years | 115 | 65.0 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 156 | 88.6 | |

| Female | 20 | 11.4 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 162 | 92.0 | |

| African American | 7 | 4.0 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 | 2.3 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Education level | |||

| High school, equivalent or less | 69 | 40.8 | |

| Some post-high-school education but below college | 85 | 50.3 | |

| College and above | 15 | 8.9 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 26 | 14.8 | |

| Unemployed | 9 | 5.1 | |

| Not in labor force | 141 | 80.1 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 100 | 56.5 | |

| Widowed | 20 | 11.3 | |

| Divorced/separated | 49 | 27.7 | |

| Never married | 8 | 4.5 | |

| Household type | |||

| With children <18 years | 27 | 15.7 | |

| Without children <18 years | 145 | 84.3 | |

| Household size | |||

| 1 adult | 50 | 29.1 | |

| 2 adults | 103 | 59.9 | |

| ≥3 adults | 19 | 11.1 | |

| Household income in the last 12 month | |||

| ≤$15,000 | 21 | 27.6 | |

| $15,000–$30,000 | 25 | 32.9 | |

| >$30,000 | 30 | 39.5 | |

| Military status | |||

| Veteran | 156 | 91.8 | |

| Non-active | 13 | 7.7 | |

| Active | 1 | <1 | |

| Branch of military | |||

| Air Force | 12 | 6.9 | |

| Army | 117 | 67.2 | |

| Marine Corps | 10 | 5.8 | |

| Navy | 32 | 18.4 | |

| Multiple branches | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Guard/Reserve Service | |||

| Yes | 52 | 30.2 | |

| No | 120 | 69.8 | |

| Years served | mean (SD) | 5.6 (5.8) | |

| Service-related Veterans Affairs-recognized disability | |||

| Yes | 57 | 33.0 | |

| No | 116 | 67.0 | |

| Service-related non-Veterans Affairs-recognized disability | |||

| Yes | 52 | 30.0 | |

| No | 121 | 69.9 | |

| Status | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veterans Affairs healthcare | |||

| Yes | 109 | 77.3 | |

| No | 32 | 22.7 | |

| Veteran Affairs disability benefits | |||

| Yes | 56 | 59.6 | |

| No | 38 | 40.4 | |

| Veteran pension | |||

| Yes | 35 | 21.1 | |

| No | 131 | 78.9 | |

| Disability payments | |||

| Yes | 57 | 36.5 | |

| No | 99 | 63.5 | |

| Employer pension/retirement fund | |||

| Yes | 37 | 22.6 | |

| No | 127 | 77.4 | |

| Social security | |||

| Yes | 100 | 58.5 | |

| No | 71 | 41.5 | |

| TANF 1 | |||

| Yes | 2 | 1.2 | |

| No | 160 | 98.8 | |

| Employment compensation | |||

| Yes | 6 | 3.7 | |

| No | 156 | 96.3 | |

| General assistance from the township trustee | |||

| Yes | 1 | 0.6 | |

| No | 161 | 99.4 | |

| SNAP 2 | |||

| Yes | 42 | 25.2 | |

| No | 125 | 74.9 | |

| Free meals, soup kitchens | |||

| Yes | 19 | 11.7 | |

| No | 143 | 88.3 | |

| Free/reduced-price meals at school/childcare | |||

| Yes | 10 | 6.2 | |

| No | 152 | 94.8 | |

| Sum of all programs reported | |||

| 0 | 21 | 11.9 | |

| 1 | 23 | 13.0 | |

| 2 | 40 | 22.6 | |

| 3 | 41 | 23.2 | |

| 4 | 25 | 14.1 | |

| 5 | 14 | 7.9 | |

| 6 | 13 | 7.3 | |

| Food security 3 | |||

| Food secure | 97 | 59.9 | |

| Food insecure | 65 | 40.1 | |

| Low food security 4 | 30 | 46 5 | |

| Very low food security 4 | 35 | 54 5 |

| Variables | Scores (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Grit (1–5 score) | 3.50 ± 0.67 |

| Help-seeking (1–7 score) | 3.48 ± 1.00 |

| Variable | Estimates ± SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Covariates + Grit | Covariates + Help-Seeking | |

| Resource use (0–6 programs) | −0.023 ± 0.07 | 0.014 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, Y.; Sneddon, D.A.; MacDermid Wadsworth, S.; Topp, D.; Sterrett, R.A.; Newton, J.R.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Grit but Not Help-Seeking Was Associated with Food Insecurity among Low Income, At-Risk Rural Veterans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032500

Qin Y, Sneddon DA, MacDermid Wadsworth S, Topp D, Sterrett RA, Newton JR, Eicher-Miller HA. Grit but Not Help-Seeking Was Associated with Food Insecurity among Low Income, At-Risk Rural Veterans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032500

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Yue, Douglas A. Sneddon, Shelley MacDermid Wadsworth, Dave Topp, Rena A. Sterrett, Jake R. Newton, and Heather A. Eicher-Miller. 2023. "Grit but Not Help-Seeking Was Associated with Food Insecurity among Low Income, At-Risk Rural Veterans" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032500