Café Food Safety and Its Impacts on Intention to Reuse and Switch Cafés during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Starbucks

Abstract

1. Introduction

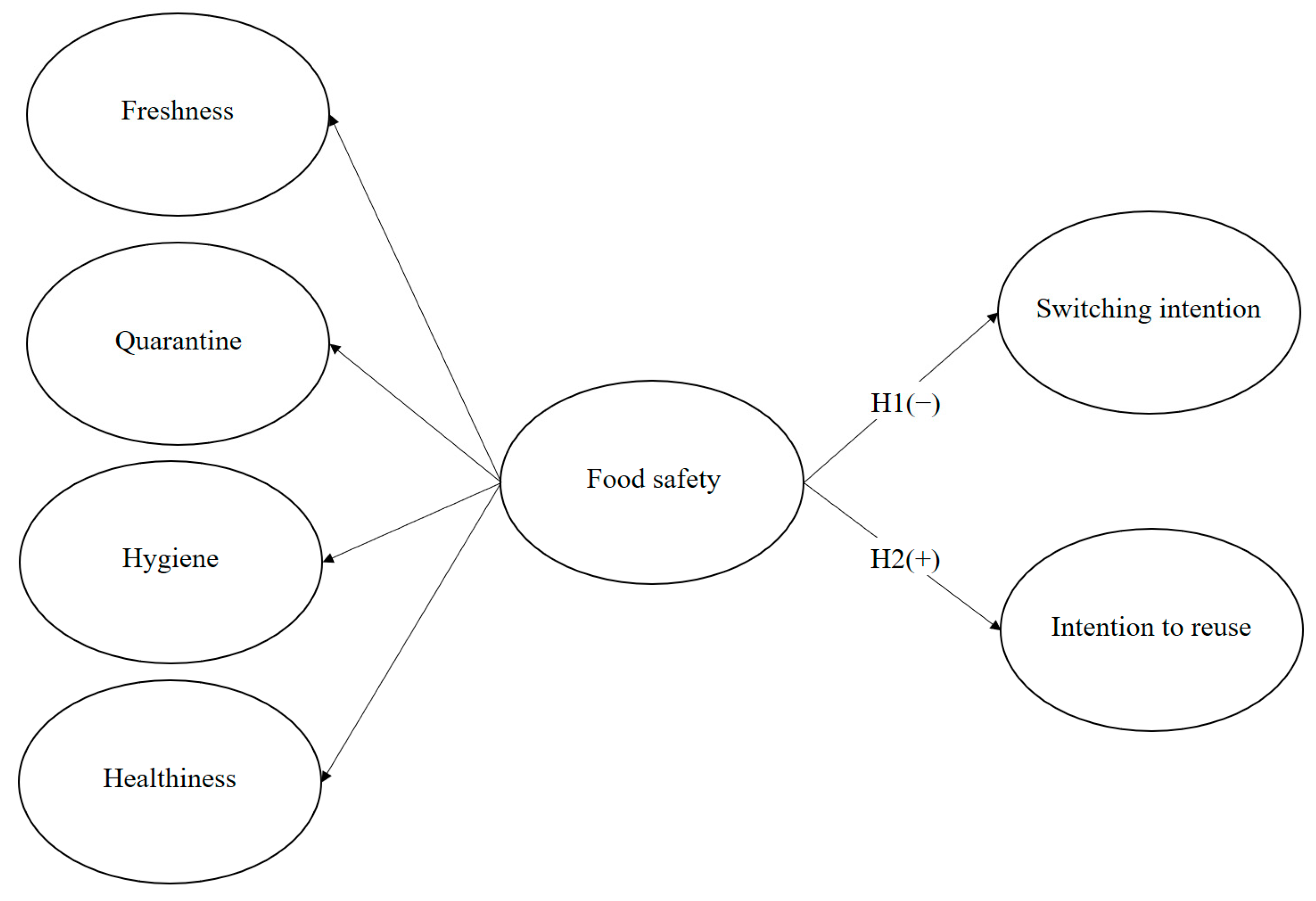

2. Review of the Literature and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Food Safety and Corporate Social Responsibility

2.2. Switching and Revisiting Intentions

3. Methods

3.1. Research Model and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Items

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Correlation Matrix

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.A.; Forster, W.R. CSR and stakeholder theory: A tale of Adam Smith. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.J.; Tewari, M. Firm characteristics, industry context, and investor reactions to environmental CSR: A stakeholder theory approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Podnar, K. Critical points of CSR-related stakeholder dialogue in practice. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2014, 23, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbots, E.J.; Coles, B. Horsemeat-gate: The discursive production of a neoliberal food scandal. Food Cul. Soc. 2013, 16, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, L.; Capitello, R.; De Salvo, M.; Longo, A.; Boeri, M. Food fraud and consumers’ choices in the wake of the horsemeat scandal. Brit. Food J. 2016, 118, 1898–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insight. Five Food Scandals That Rocked the Foodservice Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www.verdictfoodservice.com/insight/food-scandals-foodservice-industry/ (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- Schaefer, K.A.; Scheitrum, D.; Nes, K. International sourcing decisions in the wake of a food scandal. Food Pol. 2018, 81, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Food quality and safety: Consumer perception and demand. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababio, P.F.; Lovatt, P. A review on food safety and food hygiene studies in Ghana. Food Ctrl. 2015, 47, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H.; Lee, J.H. Understanding risk perception toward food safety in street food: The relationships among service quality, values, and repurchase intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Tsai, M.C. Effects of the perception of traceable fresh food safety and nutrition on perceived health benefits, affective commitment, and repurchase intention. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D.A.; Griffith, C.J. Observation of food safety practices in catering using notational analysis. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.; Conroy, D.M. When food governance matters to consumer food choice: Consumer perception of and preference for food quality certifications. Appetite 2022, 168, 105688. [Google Scholar]

- Sadílek, T. Consumer preferences regarding food quality labels: The case of Czechia. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2508–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, B.; Wong, C. Using the theory of planned behaviour to design a food hygiene intervention. Food Control 2010, 21, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lu, J. The impact of package color and the nutrition content labels on the perception of food healthiness and purchase intention. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. The impact of retailer innovativeness and food healthiness on store prestige, store trust and store loyalty. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Sacchi, G.; Carfora, V. Resilience effects in food consumption behaviour at the time of COVID-19: Perspectives from Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, K.; De Brauw, A.; Abate, G.T. Food consumption and food security during the COVID-19 pandemic in Addis Ababa. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenarides, L.; Grebitus, C.; Lusk, J.L.; Printezis, I. Food consumption behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Agribusiness 2021, 37, 44–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Moon, J.; Song, M.; Lee, W.S. Antecedents of purchase intention at Starbucks in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, L.; Lam, L.; Law, R. How locus of control shapes intention to reuse mobile apps for making hotel reservations: Evidence from Chinese consumers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A. Mobile food ordering apps: An empirical study of the factors affecting customer e-satisfaction and continued intention to reuse. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Zhu, Y. Why customers have the intention to reuse food delivery apps: Evidence from China. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruence and relationship quality in predicting switching intention: Conspicuousness of product use as a moderator variable. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 37, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, W.; Hyun, S.S. Switching intention model development: Role of service performances, customer satisfaction, and switching barriers in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Kim, W.Y. Forecasting customer switching intention in mobile service: An exploratory study of predictive factors in mobile number portability. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2008, 75, 854–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Coffee News. Nearly Four of Every Five US Coffee Shops Are Now Starbucks, Dunkin’ or JAB Brands. 2019. Available online: https://dailycoffeenews.com/2019/10/25/nearly-four-of-every-five-us-coffee-shops-are-now-starbucks-dunkin-or-jab-brands/ (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- Lamberti, L.; Lettieri, E. CSR practices and corporate strategy: Evidence from a longitudinal case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Lerro, M. Consumers’ preferences for and perception of CSR initiatives in the wine sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, T.T. Triple bottom line model and food safety in organic food and conventional food in affecting perceived value and purchase intentions. Br. Food J. 2018, 121, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzembrak, Y.; Klüche, M.; Gavai, A.; Marvin, H.J. Internet of Things in food safety: Literature review and a bibliometric analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, K.L. Green organizational culture, corporate social responsibility implementation, and food safety. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 585435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y. How does mission statement relate to the pursuit of food safety certification by food companies? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N. How does CSR of food company affect customer loyalty in the context of COVID-19: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2022, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Consumer responses to the food industry’s proactive and passive environmental CSR, factoring in price as CSR tradeoff. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ma, Q.; Morse, S. Motives for corporate social responsibility in Chinese food companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuganesan, S.; Guthrie, J.; Ward, L. Examining CSR disclosure strategies within the Australian food and beverage industry. Account. Forum 2010, 34, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.; Platts, J.; Gregory, M. Exploration of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in multinational companies within the food industry. Queen’s Discuss. Pap. Ser. Corp. Responsib. Res. 2009, 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peri, C. The universe of food quality. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Cembalo, L. Opening the black box of food quality in the short supply chain: Effects of conventions of quality on consumer choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J.; Vaz-Pires, P.; Câmara, J.S. From aquaculture production to consumption: Freshness, safety, traceability and authentication, the four pillars of quality. Aquaculture 2020, 518, 734857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, J.V. Food quality and consumer choice. Br. Food J. 1992, 94, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prater, C.; Wagner, N.D.; Frost, P.C. Interactive effects of genotype and food quality on consumer growth rate and elemental content. Ecology 2017, 98, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.; Choi, Y. Employee perceptions of hotel CSR activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3355–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M. Changes in the food-related behaviour of Italian consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Foods 2021, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, K. Factors influencing customers’ continuance usage intention of food delivery apps during COVID-19 quarantine in Mexico. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 833–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifle Mekonen, Y.; Adarkwah, M.A. Volunteers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Intrinsic, extrinsic, or altruistic motivation? Postgraduate international students in China. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2021, 48, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.T.; Sue, H.J.; Chen, P.H. The impact of community housing characteristics and epidemic prevention measures on residents’ perception of epidemic prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanka, R.J.; Buff, C. COVID-19 generation: A conceptual framework of the consumer behavioral shifts to be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, K.; Ranjan, S. Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Pediatr. 2020, 87, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wu, K.; Lin, K. Life or livelihood? Mental health concerns for quarantine hotel workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, A.; Raab, C.; Tang, J.; Han, W. Exploring the motivations to use online meal delivery platforms: Before and during quarantine. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, D.M. Health education models and food hygiene education. J. R. Soc. Health 1995, 115, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baş, M.; Ersun, A.Ş.; Kıvanç, G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers’ in food businesses in Turkey. Food Control 2006, 17, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, P. Food hygiene training: Introducing the food hygiene training model. Food Control 2010, 21, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.B.; Hogg, T.; Otero, J.G. Food handlers’ knowledge on food hygiene: The case of a catering company in Portugal. Food Control 2012, 23, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, I.; Chatterjee, S. Urban street vending practices: An investigation of ethnic food safety knowledge, attitudes, and risks among untrained Chinese vendors in Chinatown, Kolkata. J. Ethn. Foods 2018, 5, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, T.; Tilley, E.; Chidziwisano, K.; Malolo, R.; Musaya, J. Health outcomes of an integrated behaviour-centred water, sanitation, hygiene and food safety intervention–a randomised before and after trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, V.; Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P. Perceived healthiness of food. If it’s healthy, you can eat more! Appetite 2009, 52, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Toledo, E.; De Irala, J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Pla-Vidal, J.; Martínez-González, M.A. Fast-food and commercial baked goods consumption and the risk of depression. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.T.; Treat, T.A. Perceptions of food healthiness among free-living women. Appetite 2015, 95, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundijo, D.A.; Tas, A.A.; Onarinde, B.A. An assessment of nutrition information on front of pack labels and healthiness of foods in the United Kingdom retail market. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Vermeir, I.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M. Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: A cross-national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, P.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, H. Recent advances in the application of metabolomics for food safety control and food quality analyses. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1448–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Carrero, M. The mediating effect of satisfaction on consumers’ switching intention. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Exploring the relationship between satisfaction, trust and switching intention, repurchase intention in the context of Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, Y.C.; Zhu, Q. Investigating user switching intention for mobile instant messaging application: Taking WeChat as an example. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Han, H.; Oh, M. Travelers’ switching behavior in the airline industry from the perspective of the push-pull-mooring framework. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, D.; Marimuthu, M.; Hyun, S.S. Influence of perceived service fairness on relationship quality and switching intention: An empirical study of restaurant experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. Animosity and switching intention: Moderating factors in the decision making of Chinese ethnic diners. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2019, 60, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, Y.C. The influence of social presence on customer intention to reuse online recommender systems: The roles of personalization and product type. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, Y.; Fu, Z.; Alford, P. An empirical study on behavioural intention to reuse e-learning systems in rural China. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Sahadev, S.; Purani, K. Psychological contract violation and customer intention to reuse online retailers: Exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.C.; Bae, J.; Kim, K.H. The effect of perceived agility on intention to reuse Omni-channel: Focused on mediating effect of integration quality of Omni-channel. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. The role of satisfaction on customer reuse to airline services: An application of Big Data approaches. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Roberts, K.R. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict food safety behavioral intention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.P.; Tsai, H.Y.; Ruangkanjanases, A. The determinants for food safety push notifications on continuance intention in an e-appointment system for public health medical services: The perspectives of UTAUT and information system quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Nguyen, N. A moderated mediation study of consumer extrinsic motivation and CSR beliefs towards organic drinking products in an emerging economy. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Yeh, Q.J.; Huang, C.Y. Understanding consumer’switching intention toward traceable agricultural products: Push-pull-mooring perspective. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 46, 870–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.S.; Hsu, H. Esthetic dining experience: The relations among aesthetic stimulation, pleasantness, memorable experience, and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Kim, H.J. Positive and negative eWOM motivations and hotel customers’ eWOM behavior: Does personality matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Jang, J. Fostering service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through reducing role stressors: An examination of the role of social capital. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3567–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Yang, H.; Mattila, A.S. The impact of customer loyalty and restaurant sanitation grades on revisit intention and the importance of narrative information: The case of New York restaurant sanitation grading system. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2018, 59, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, H.; Gabric, D.; Holah, J. Handbook of Hygiene Control in the Food Industry; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, T.; Masuku, H.; Rippon, S.; Kubwalo, H. Achieving an integrated approach to food safety and hygiene—Meeting the sustainable development goals in sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, M.; Gvili, Y.; Tal, A. Moving towards healthy: Cuing food healthiness and appeal. J. Soc. Mark. 2020, 11, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

| Construct | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Freshness | FR1 | The taste of Starbucks products is great. |

| FR2 | Starbucks offers fresh products. | |

| FR3 | Starbucks products are delicious. | |

| FR4 | Starbucks uses fresh ingredients. | |

| Quarantine | QR1 | Starbucks is good at COVID-19 quarantine. |

| QR2 | Starbucks adequately maintains COVID-19 quarantine. | |

| QR3 | Starbucks employees perform well in terms of COVID-19 quarantine. | |

| QR4 | COVID-19 quarantine is effectively implemented at Starbucks. | |

| Hygiene | HY1 | Starbucks products are hygienic. |

| HY2 | Starbucks products are clean. | |

| HY3 | Sanitation of Starbucks goods is effectively managed. | |

| HY4 | Starbucks food is clean and hygienic. | |

| Healthiness | HE1 | Starbucks products are healthy. |

| HE2 | Starbucks products improve my health. | |

| HE3 | Starbucks offers products that are not good for health. | |

| HE4 | Starbucks products are low in calories. | |

| Switching intention | SI1 | I will use other goods instead of Starbucks goods. |

| SI2 | I will buy another brand of coffee, rather than Starbucks. | |

| SI3 | I intend to switch from Starbucks products. | |

| Intention to reuse | IR1 | I will reuse Starbucks. |

| IR2 | I will visit Starbucks again. | |

| IR3 | I intend to purchase Starbucks products again. | |

| IR4 | I am willing to repurchase Starbucks products. |

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 289 | 61.0 |

| Female | 185 | 39.0 |

| Age: 20s or younger | 188 | 39.6 |

| 30s | 181 | 38.2 |

| 40s | 60 | 12.7 |

| 50s or older | 45 | 9.5 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| <USD 2000 | 94 | 19.8 |

| USD 2000–3999 | 138 | 29.1 |

| USD 4000–5999 | 97 | 20.5 |

| USD 6000–7999 | 45 | 9.5 |

| USD 8000–9999 | 47 | 9.9 |

| >USD 10,000 | 53 | 11.2 |

| Weekly visiting frequency | ||

| <1 time | 163 | 34.4 |

| 1–2 times | 192 | 40.5 |

| 3–5 times | 94 | 19.8 |

| >5 times | 25 | 5.3 |

| Construct (AVE) | Subdimension | Code | Mean | SD | Loading | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food safety (0.582) | Freshness | FR1 | 4.11 | 0.89 | 0.710 | 0.939 |

| FR2 | 3.93 | 0.89 | 0.723 | |||

| FR3 | 4.13 | 0.86 | 0.718 | |||

| FR4 | 3.87 | 0.90 | 0.721 | |||

| Quarantine | QR1 | 3.75 | 0.97 | 0.804 | ||

| QR2 | 3.76 | 0.94 | 0.836 | |||

| QR3 | 3.89 | 0.88 | 0.759 | |||

| QR4 | 3.82 | 0.88 | 0.780 | |||

| Hygiene | HY1 | 4.04 | 0.85 | 0.789 | ||

| HY2 | 4.05 | 0.87 | 0.780 | |||

| HY3 | 4.02 | 0.87 | 0.763 | |||

| HY4 | 4.03 | 0.88 | 0.773 | |||

| Healthiness | HE1 | 3.32 | 1.17 | 0.859 | ||

| HE2 | 3.14 | 1.23 | 0.861 | |||

| HE3 | 3.33 | 1.11 | 0.752 | |||

| HE4 | 3.18 | 1.21 | 0.806 | |||

| Switching intention (0.551) | SI1 | 3.33 | 1.15 | 0.769 | 0.783 | |

| SI2 | 3.23 | 1.22 | 0.831 | |||

| SI3 | 3.18 | 1.16 | 0.608 | |||

| Intention to reuse (0.685) | IR1 | 4.08 | 0.95 | 0.798 | 0.897 | |

| IR2 | 4.16 | 0.91 | 0.828 | |||

| IR3 | 4.16 | 0.92 | 0.848 | |||

| IR4 | 4.08 | 0.95 | 0.836 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Food safety | 0.763 | ||

| 2. Switching intention | 0.067 (0.001) | 0.742 | |

| 3. Intention to reuse | 0.846 * (0.715) | –0.158 * (0.002) | 0.828 |

| H | Path | Standard Beta | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Food safety→Switching intention | 0.004 | 0.936 | Not supported |

| H2 | Food safety→Intention to reuse | 0.848 * | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, Y.; Lee, W.S.; Moon, J. Café Food Safety and Its Impacts on Intention to Reuse and Switch Cafés during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Starbucks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032625

Ji Y, Lee WS, Moon J. Café Food Safety and Its Impacts on Intention to Reuse and Switch Cafés during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Starbucks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032625

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Yunho, Won Seok Lee, and Joonho Moon. 2023. "Café Food Safety and Its Impacts on Intention to Reuse and Switch Cafés during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Starbucks" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032625

APA StyleJi, Y., Lee, W. S., & Moon, J. (2023). Café Food Safety and Its Impacts on Intention to Reuse and Switch Cafés during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Starbucks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032625