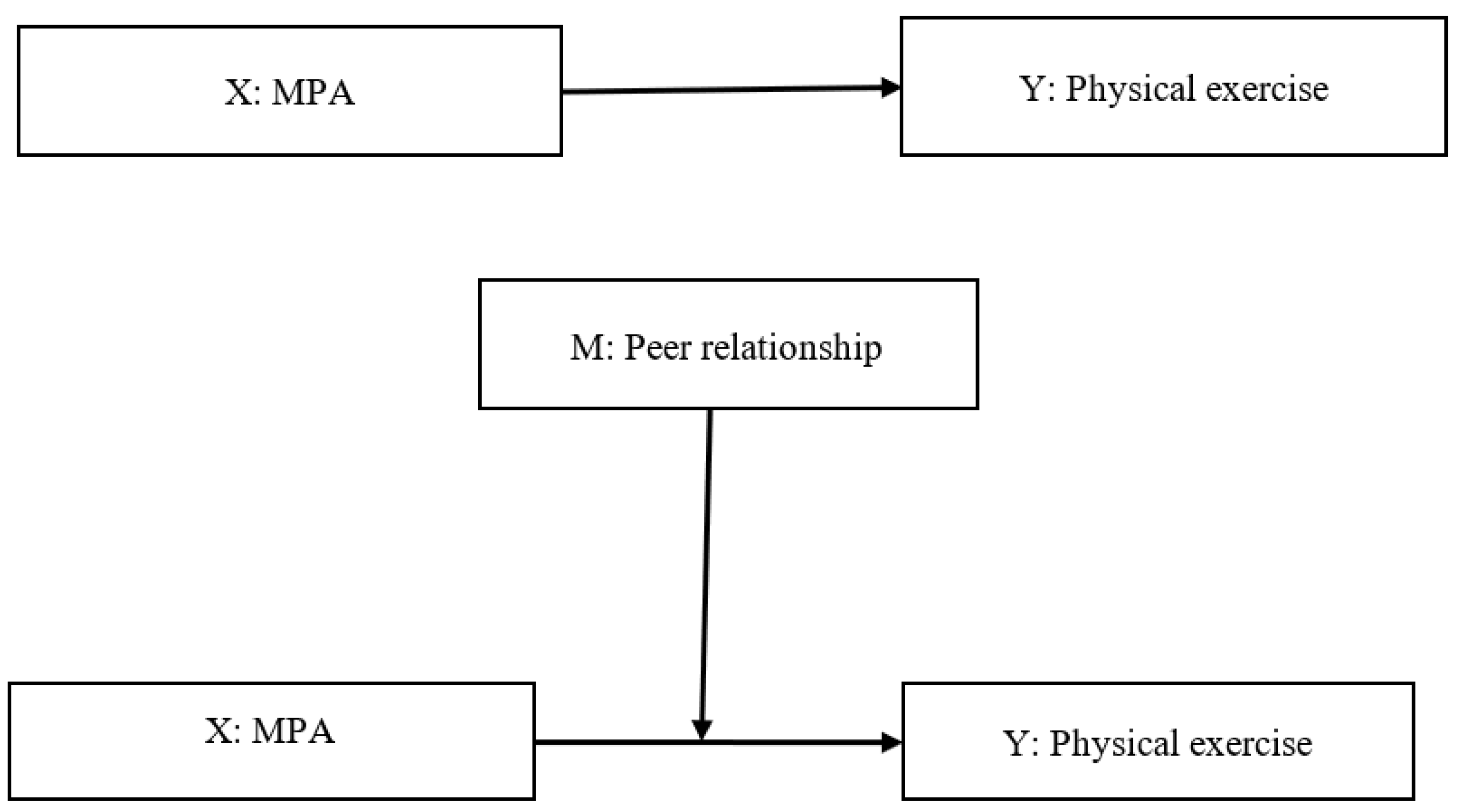

Effect of Mobile Phone Addiction on Physical Exercise in University Students: Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Mobile Phone Addiction Tendency Scale (MPATS)

2.2.2. Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3)

2.2.3. Peer Rating Scale (PRS)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Trends

3.2. Correlation Analysis

3.3. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.-E.; Kim, J.-W.; Jee, Y.-S. Relationship between smartphone addiction and physical activity in Chinese international students in Korea. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniewicz, C.A.; Tiamiyu, M.F.; Weeks, J.W.; Elhai, J.D. Problematic smartphone use and relations with negative affect, fear of missing out, and fear of negative and positive evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Lu, T.; Tao, B.; Gao, Y.; Yan, J. The Relationship between Physical Activity and College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction: The Chain-Based Mediating Role of Psychological Capital and Social Adaptation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, M.; Chen, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, J. The relationship between physical exercise and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: Testing mediation and moderation effects. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1000109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, G.R.; Garcia, L.F.; Bertolini, S.M.M.G.; Lucena, T.F.R. The Head Down Generation: Musculoskeletal Symptoms and the Use of Smartphones Among Young University Students. Telemed. e-Health 2019, 25, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.A.; Hutchinson, N.T.; Powers, S.K.; Roberts, W.O.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Radak, Z.; Berkes, I.; Boros, A.; Boldogh, I.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sport. Med. Health Sci. 2020, 2, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). Chinese Statistical Report on the Development of the Internet; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann, D.; Pfirrmann, D.; Heller, S.; Dietz, P.; Reichel, J.L.; Werner, A.M.; Schäfer, M.; Tibubos, A.N.; Deci, N.; Letzel, S.; et al. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in University Students-The Role of Gender, Age, Field of Study, Targeted Degree, and Study Semester. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Li, Y.Q. Physical activity and mental health in sports university students during the COVID-19 school confinement in Shanghai. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomee, S. Mobile Phone Use and Mental Health. A Review of the Research That Takes a Psychological Perspective on Exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honglv, X.; Jian, T.; Jiaxing, Y.; Yunpeng, S.; Chuanzhi, X.; Mengdie, H.; Lum, G.G.A.; Dongyue, H.; Lin, L. Mobile phone use addiction, insomnia, and depressive symptoms in adolescents from ethnic minority areas in China: A latent variable mediation model. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 320, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, P.A.; Mccarthy, S. Antecedents and consequences of problematic smartphone use: A systematic literature review of an emerging research area. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106414. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, D.A.; Davidson, B.I.; Shaw, H.; Geyer, K. Do smartphone usage scales predict behavior? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2019, 130, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atış Akyol, N.; Atalan Ergin, D.; Krettmann, A.K.; Essau, C.A. Is the relationship between problematic mobile phone use and mental health problems mediated by fear of missing out and escapism? Addict. Behav. Rep. 2021, 14, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, X.; Chamarro, A.; Oberst, U.; Rodrigo, B.; Prades, M. Problematic Use of the Internet and Smartphones in University Students: 2006–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Asbury, K.; Griffiths, M.D. An Exploration of Problematic Smartphone Use among Chinese University Students: Associations with Academic Anxiety, Academic Procrastination, Self-Regulation and Subjective Wellbeing. Int. J. Mental. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 596–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Min, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Min, K.B. Accident risk associated with smartphone addiction: A study on university students in Korea. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The Self System in Reciprocal Determinism. Am. Psychol. 1978, 33, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Silva, E.S.; Hallgren, M.; Ponce De Leon, A.; Dunn, A.L.; Deslandes, A.C.; et al. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvy, S.J.; Bowker, J.W.; Roemmich, J.N.; Romero, N.; Kieffer, E.; Paluch, R.; Epstein, L.H. Peer influence on children’s physical activity: An experience sampling study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008, 33, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorhees, C.C.; Murray, D.; Welk, G.; Birnbaum, A.; Ribisl, K.M.; Johnson, C.C.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Saksvig, B.; Jobe, J.B. The role of peer social network factors and physical activity in adolescent girls. Am. J. Health Behav. 2005, 29, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, M.S.; Leone, M.A.; Ayers, T.S.; Heo, M.; Pietrobelli, A. Weight criticism during physical activity, coping skills, and reported physical activity in children. Pediatrics 2002, 110, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer, B.J.; Ladd, G.W. Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment? Child. Dev. 1996, 67, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, S.J.; Greenberg, M.A. Mending Broken Hearts: Effects of Expressive Writing on Mood, Cognitive Processing, Social Adjustment and Health Following a Relationship Breakup. Psychol. Health 2002, 17, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Pang, F.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Peng, T. The association between autistic traits and excessive smartphone use in Chinese college students: The chain mediating roles of social interaction anxiety and loneliness. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 131, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.-Q. How to Determine the Sample Size in Sampling Survey. Stat. Decis. 2012, 22, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.; Zhou, Z.K.; Chen, W.; You, Z.L.; Zhai, Z.Y. Compilation of the Mobile Phone Addiction Scale for College Students. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2012, 26, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.Q. College students’ stress levels and their relationship to physical exercise. Chin. J. Ment. Health 1994, 8, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, S.R.; Dodge, K.A. Identifying Children Who Are Rejected by Their Peers. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L. Research on Self-Concept and School Adaptation of Junior High School Students. Master’s Thesis, Northwestern University, Xi’an, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, O.W.; Holland, K.E.; Elliott, L.D.; Duffey, M.; Bopp, M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on US College Students’ Physical Activity and Mental Health. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, S.; Meng, S.; Lee, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, Y. Promoting exercise behavior and cardiorespiratory fitness among college students based on the motivation theory. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Skelton, D.A. Prevalence of sedentary behavior in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 6645–6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buizza, C.; Bazzoli, L.; Ghilardi, A. Changes in College Students Mental Health and Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2022, 7, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepp, A.; Barkley, J.E.; Sanders, G.J.; Rebold, M.; Gates, P. The relationship between cell phone use, physical and sedentary activity, and cardiorespiratory fitness in a sample of U.S. college students. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towne, S.D.; Ory, M.G.; Smith, M.L.; Peres, S.C.; Pickens, A.W.; Mehta, R.K.; Benden, M. Accessing physical activity among young adults attending a university: The role of sex, race/ethnicity, technology use, and sleep. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhai, X.; Li, S.; Shi, Y.; Fan, X. The Relationship between Physical Activity, Mobile Phone Addiction, and Irrational Procrastination in Chinese College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselager, G.J.; Hartup, W.W.; van Lieshout, C.F.; Riksen-Walraven, J.M. Similarities between Friends and Nonfriends in Middle Childhood. Child. Dev. 1998, 69, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L.; Ullrich-French, S.; Walker, E.; Hurley, K.S. Peer Relationship Profiles and Motivation in Youth Sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeer, L.; Stylianou, M.; Gomersall, S.R. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Educational Outcomes among Australian University Students: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masaeli, N.; Billieux, J. Is Problematic Internet and Smartphone Use Related to Poorer Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of Available Evidence and Assessment Strategies. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2022, 9, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, S. Smartphone addiction and associated consequences: Role of loneliness and self-regulation. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; He, Y.; Yang, T.; Ren, L.; Qiu, R.; Zhu, X.; Wu, S. The roles of behavioral inhibition/activation systems and impulsivity in problematic smartphone use: A network analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zheng, H.; Sun, R.; Lu, S. Parent-adolescent relationships, peer relationships, and adolescent mobile phone addiction: The mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Addict. Behav. 2022, 129, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, R.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X. Negative life events, depression, and mobile phone dependency among left-behind adolescents in rural China: An interpersonal perspective. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Li, B.; Wang, G.X.; Ke, Y.Z.; Meng, S.Q.; Li, Y.X.; Cui, Z.L.; Tong, W.X. Physical Fitness, Exercise Behaviors, and Sense of Self-Efficacy among College Students: A Descriptive Correlational Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 932014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| 4959 | 100.0 | ||

| Grade | |||

| Freshman | 1708 | 34.4 | |

| Sophomore | 1752 | 35.3 | |

| Junior | 840 | 16.9 | |

| Senior | 659 | 13.3 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1878 | 37.9 | |

| Female | 3081 | 62.1 |

| Descriptive | Statistical Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | χ2 | p | Cramer’s V | |||

| Total | |||||||

| Low | 3666 | 73.9 | |||||

| Middle | 690 | 13.9 | |||||

| High | 603 | 12.2 | |||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male (n = 1878) | Low | 1022 | 54.4 | 637.825 | <0.001 | 0.359 | |

| Middle | 401 | 21.4 | |||||

| High | 455 | 24.2 | |||||

| Female (n = 3081) | Low | 2644 | 85.8 | ||||

| Middle | 289 | 9.4 | |||||

| High | 148 | 4.8 | |||||

| Grade | |||||||

| Freshman (n = 1708) | Low | 1197 | 70.1 | 29.792 | <0.001 | 0.078 | |

| Middle | 274 | 16.0 | |||||

| High | 237 | 13.9 | |||||

| Sophomore (n = 1752) | Low | 1349 | 77.0 | ||||

| Middle | 228 | 13.0 | |||||

| High | 175 | 10.0 | |||||

| Junior (n = 840) | Low | 638 | 76.0 | ||||

| Middle | 92 | 11.0 | |||||

| High | 110 | 13.1 | |||||

| Senior (n = 659) | Low | 482 | 73.1 | ||||

| Middle | 96 | 14.6 | |||||

| High | 81 | 12.3 | |||||

| Total | Male | Female | F | p | η2 | Freshman | Sophomore | Junior | Senior | F | p | η2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||||

| Withdrawal symptoms | 15.962 | 5.891 | 15.999 | 6.142 | 15.939 | 5.734 | 2.037 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 15.490 | 5.321 | 16.296 | 5.812 | 16.394 | 6.564 | 15.745 | 6.488 | 7.359 | <0.001 | 0.087 |

| Highlight behavior | 8.725 | 4.096 | 9.022 | 4.371 | 8.543 | 3.909 | 4.785 | <0.001 | 0.107 | 7.812 | 3.442 | 9.192 | 4.111 | 9.419 | 4.632 | 8.962 | 4.466 | 45.846 | <0.001 | 0.062 |

| Social comfort | 7.712 | 3.343 | 7.665 | 3.428 | 7.741 | 3.291 | 1.934 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 7.466 | 3.212 | 7.871 | 3.228 | 7.930 | 3.603 | 7.651 | 3.591 | 5.679 | 0.001 | 0.044 |

| Mood alteration | 6.924 | 3.172 | 6.953 | 3.312 | 6.906 | 3.084 | 2.281 | <0.001 | 0.013 | 6.452 | 2.816 | 7.164 | 3.150 | 7.350 | 3.535 | 6.964 | 3.456 | 21.303 | <0.001 | 0.172 |

| MPATS | 39.322 | 15.139 | 39.638 | 16.047 | 39.130 | 14.557 | 2.748 | <0.001 | 0.031 | 37.220 | 12.988 | 40.523 | 15.075 | 41.093 | 17.259 | 39.322 | 16.896 | 18.677 | <0.001 | 0.145 |

| Welcoming | 11.953 | 2.987 | 12.104 | 3.199 | 11.861 | 2.846 | 1.316 | 0.156 | 0.026 | 11.734 | 2.862 | 12.076 | 2.975 | 12.206 | 3.070 | 11.868 | 3.185 | 6.260 | <0.001 | 0.040 |

| Autism | 17.743 | 3.819 | 17.922 | 4.025 | 17.634 | 3.684 | 2.047 | 0.004 | 0.035 | 17.575 | 3.664 | 17.913 | 3.782 | 17.874 | 3.920 | 17.560 | 4.146 | 3.093 | 0.026 | 0.026 |

| Exclusiveness | 14.326 | 2.111 | 14.444 | 2.215 | 14.255 | 2.041 | 1.452 | 0.087 | 0.016 | 14.320 | 2.121 | 14.366 | 2.082 | 14.368 | 2.116 | 14.184 | 2.151 | 0.329 | 0.263 | 0.001 |

| PRS | 44.022 | 7.735 | 44.470 | 8.158 | 43.749 | 7.454 | 1.733 | 0.022 | 0.234 | 43.629 | 7.714 | 44.356 | 7.660 | 44.448 | 7.572 | 43.612 | 8.131 | 4.027 | 0.007 | 0.154 |

| Withdrawal Symptoms | Highlight Behavior | Social Comfort | Mood Alteration | MPATS | Welcoming | Autism | Exclusiveness | PRS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal symptoms | |||||||||

| Highlight behavior | 0.804 ** | ||||||||

| Social comfort | 0.742 ** | 0.697 ** | |||||||

| Mood alteration | 0.795 ** | 0.805 ** | 0.699 ** | ||||||

| MPATS | 0.944 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.852 ** | 0.895 ** | |||||

| Welcoming | −0.285 ** | −0.329 ** | −0.376 ** | −0.310 ** | −0.348 ** | ||||

| Autism | −0.236 ** | −0.331 ** | −0.294 ** | −0.303 ** | −0.317 ** | 0.506 ** | |||

| Exclusiveness | −0.235 ** | −0.329 ** | −0.297 ** | −0.298 ** | −0.312 ** | 0.519 ** | 0.794 ** | ||

| PRS | −0.291 ** | −0.382 ** | −0.373 ** | −0.353 ** | −0.377 ** | 0.758 ** | 0.911 ** | 0.870 ** | |

| PARS-3 | −0.262 ** | −0.256 ** | −0.311 ** | −0.269 ** | −0.279 ** | 0.275 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.209 ** |

| Model | Model Summary | ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | ΔR2 | df 1 | df 2 | Sig. F Change | F | p | |

| 1 | 0.112 | 0.120 | 2 | 3130 | <0.001 | 36.610 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.112 | 0.030 | 1 | 3129 | 0.044 | 31.071 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, Y.; Qin, G.; Han, S.; Ke, Y.; Meng, S.; Tong, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; Shi, W. Effect of Mobile Phone Addiction on Physical Exercise in University Students: Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032685

Han Y, Qin G, Han S, Ke Y, Meng S, Tong W, Guo Q, Li Y, Ye Y, Shi W. Effect of Mobile Phone Addiction on Physical Exercise in University Students: Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032685

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Yahui, Guoyou Qin, Shanshan Han, Youzhi Ke, Shuqiao Meng, Wenxia Tong, Qiang Guo, Yaxing Li, Yupeng Ye, and Wenya Shi. 2023. "Effect of Mobile Phone Addiction on Physical Exercise in University Students: Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032685

APA StyleHan, Y., Qin, G., Han, S., Ke, Y., Meng, S., Tong, W., Guo, Q., Li, Y., Ye, Y., & Shi, W. (2023). Effect of Mobile Phone Addiction on Physical Exercise in University Students: Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032685