The Effect of Publicly Available COVID-19 Information on the Functioning of Society, Businesses, Government and Local Institutions: A Case Study from Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Did publicly available information about the COVID-19 outbreak situation in Poland affect the frequency with which residents of Rybnik and the surrounding areas chose to stay in their houses or apartment, and was the operation of businesses indirectly relevant here?

- Did publicly available information about the COVID-19 outbreak situation in Poland affect the functioning of businesses in and around Rybnik, and was the functioning of public institutions indirectly relevant here?

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Purpose of the Study

- Did publicly available information about the COVID-19 outbreak situation in Poland affect the frequency with which residents of Rybnik and the surrounding areas chose to stay in their houses or apartments, and was the functioning of businesses indirectly relevant here?

- Did publicly available information about the situation related to the COVID-19 epidemic in Poland affect the functioning of businesses in Rybnik and the surrounding areas, and was the functioning of public institutions of indirect relevance here?

3.2. Research Tool

3.3. The Subject of Statistical Analysis

- The number of new cases of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection (in thousands) in Poland (“New Cases”);

- The number of deaths caused by SARS-CoV-2 viral infection in Poland (“Deaths”);

- The number of people quarantined (in thousands) due to the COVID-19 outbreak (“Quarantine”).

- Households, including residential buildings, collective housing, and dwellings;

- The business sector, including industry, commerce and services;

- Government and local government institutions, including schools, kindergartens and other government and local government institutions.

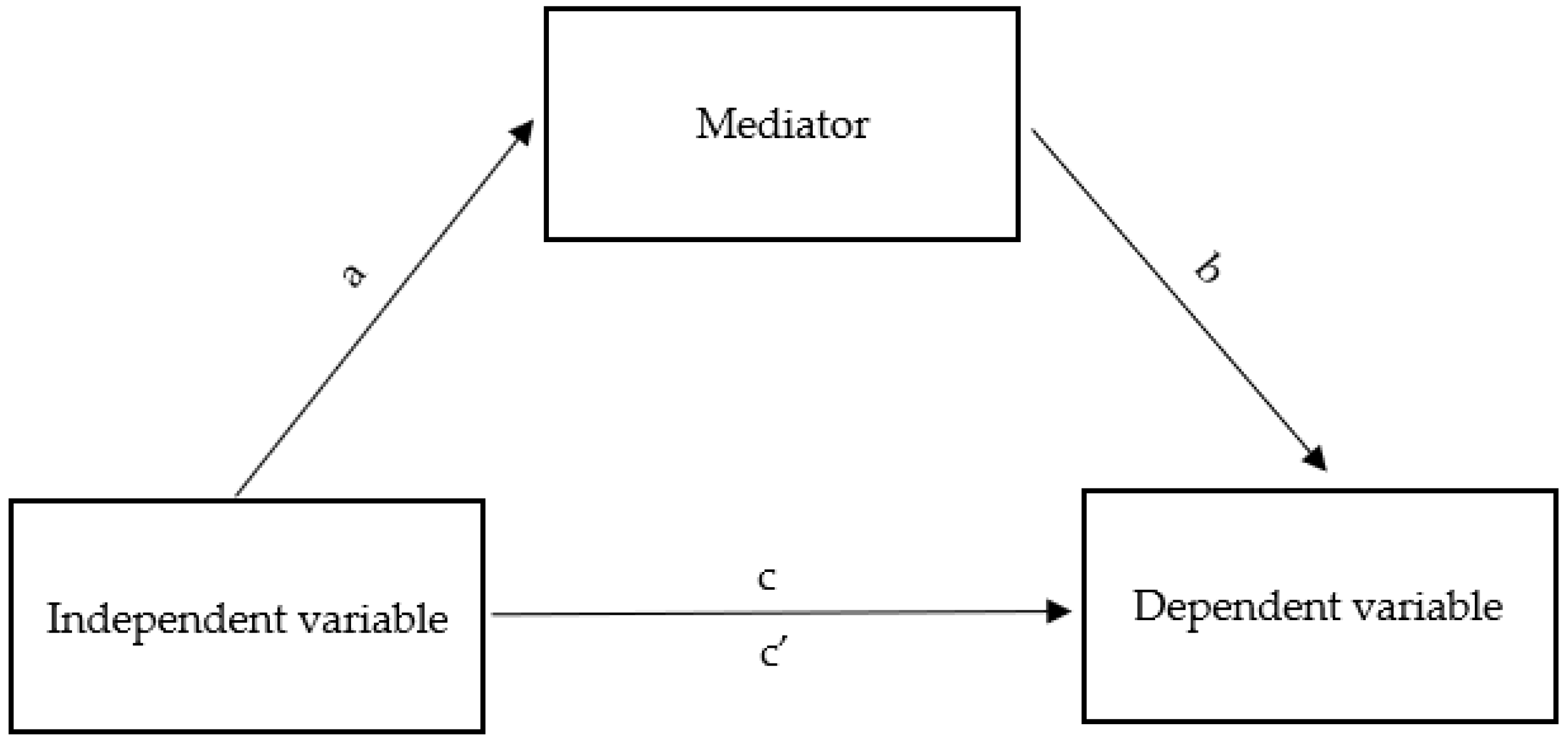

3.4. Methodology of Statistical Analysis

- independent variable with the dependent variable (direct dependence; path c),

- independent variable with a mediator (path a) and mediator with the dependent variable (path b),

- independent variable with the dependent variable (direct dependence) when both the independent variable and the mediator are included in the model (path c′) [50].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Total Results—Variables Included in the Research Model

4.2. COVID-19 and Staying at Home—The Mediating Role of Corporate Functioning

4.2.1. New Cases of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Poland

4.2.2. Deaths Due to SARS-CoV-2 Viral Infection in Poland

4.2.3. People Quarantined in Connection with COVID-19 Outbreak in Poland

4.3. COVID-19 and the Functioning of Businesses—The Mediating Role of the Functioning of Government and Local Government Institutions

4.3.1. New Cases of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Poland

4.3.2. Deaths Caused by SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Poland

4.3.3. People Quarantined in Connection with COVID-19 Outbreak in Poland

4.4. Summary of the Model of the Mediating Role of Mediators between Independent Variables and Dependent Variables

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Migliore, G.; Rizzo, G.; Schifani, G.; Quatrosi, G.; Vetri, L.; Testa, R. Ethnocentrism Effects on Consumers’ Behavior during COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Belle, M.A.; Ntim, S.Y.; Wu, Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Aboagye, M.O.; Ren, J. COVID-19 Pandemic and International Students’ Mental Health in China: Age, Gender, Chronic Health Condition and Having Infected Relative as Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikacic, M.; Kumric, M.; Baricevic, M.; Tokic, D.; Stojanovic Stipic, S.; Cvitkovic, I.; Supe Domic, D.; Ticinovic Kurir, T.; Bozic, J. Dynamic of Serum TWEAK Levels in Critically Ill COVID-19 Male Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, P. Trauma Pandemii COVID-19 w Polskim Społeczeństwie; CeDeWu: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Zachorowania w Polsce—Aktualne Dane. Available online: https://www.mp.pl/pacjent/choroby–zakazne/koronawirus/koronawirus–warto–wiedziec/230267,COVID-19–zachorowania–w–polsce–aktualne–dane (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Gliński, Z.; Żmuda, A. Koronawirusy i koronawirozy człowieka i zwierząt. Życie Weter. 2020, 95, 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Thill, J.-C. Associations between COVID-19 Pandemic, Lockdown Measures and Human Mobility: Longitudinal Evidence from 86 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, H.; Heywood, A.E.; Leask, J.; Sheel, M.; Thomas, S.; Durrheim, D.N.; Bolsewicz, K.; Kaur, R. COVID-19 is rapidly changing: Examining public perceptions and behaviors in response to this evolving pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluwe-Schiavon, B.; Viola, T.W.; Bandinelli, L.P.; Castro, S.C.C.; Kristensen, C.H.; Costa da Costa, J.; Grassi-Oliveira, R. A behavioral economic risk aversion experiment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieślik, T.; Narloch, P.; Kogut, K.; Szurlej, A. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na zużycie gazu zmiennego przez odbiorców komercyjnych w wybranym mieście w Polsce. Rynek Energii 2021, 3, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta–analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothman, S.A.; Alghannam, A.F.; Almasud, A.A.; Altalhi, A.S.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Lifestyle behaviors trend and their relationship with fear level of COVID-19: Cross–sectional study in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons Leigh, J.; Fiest, K.; Brundin-Mather, R.; Plotnikoff, K.; Soo, A.; Sypes, E.E.; Whalen-Browne, E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Burns, K.E.A.; Fox-Robichaud, A.; et al. A national cross–sectional survey of public perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic: Self–reported beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novita, S.; Andriani, D.; Erika; Lipowski, M.; Lipowska, M. Anxiety towards COVID-19, Fear of Negative Appearance, Healthy Lifestyle, and Their Relationship with Well–Being during the Pandemic: A Cross–Cultural Study between Indonesia and Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Nguyen, N.P.; Nguyen, D.V.; Chi, H. The COVID-19 pandemic: Workplace safety management practices, job insecurity, and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Saf Sci. 2022, 145, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raport, Finanse Polaków w Czasie COVID-19. Jak Pandemia Wpłynęła na Portfele i Zwyczaje Finansowe Polaków? Available online: https://frrf.pl/raport–finanse–polakow–w–czasie–COVID-19–jak–pandemia–wplynela–na–portfele–i–zwyczaje–finansowe–polakow/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- GUS: Sytuacja Gospodarstw Domowych w 2020 r. w Świetle Wyników Badania Budżetów Gospodarstw Domowych. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fstat.gov.pl%2Ffiles%2Fgfx%2Fportalinformacyjny%2Fpl%2Fdefaultaktualnosci%2F5486%2F3%2F20%2F1%2Fsytuacja_gospodarstw_domowych_w_2020_w_swietle_wynikow_badania_budzetow_gospodarstw_domowych.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Skrabacz, A. Wpływ pandemii koronawirusa na stan bezpieczeństwa społeczno–ekonomicznego Polaków. Bezpieczeństwo. Teor. Prakt. 2021, 2, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskafi, M.; Taneja, P.; Ulfarsson, G.F. Cruising Under and Post the COVID Pandemic: Toward Realization of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajner, P. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na sytuację na rynkach rolnych w Polsce. Ubezpieczenia W Rol.—Mater. I Stud. 2020, 1, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtanowicz, K.; Białas, A. Social assistance in the face of the crisis produced by the pandemic. Pr. Soc. 2020, 35, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson–Clement, C.; Pigalle, E. What can we learn from COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on human behaviour? The case of France’s lockdown. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Qamar, A.H. Risk Perception and Protective Behavior in the Context of COVID-19: A Qualitative Exploration. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 2021, 13, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOS: Ocena Sytuacji Finansowej Gospodarstw Domowych po Roku Pandemii. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2021/K_045_21.PDF (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Zaman, U.; Barnes, S.J.; Abbasi, S.; Anjam, M.; Aktan, M.; Khwaja, M.G. The Bridge at the End of the World: Linking Expat’s Pandemic Fatigue, Travel FOMO, Destination Crisis Marketing, and Vaxication for “Greatest of All Trips”. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F.; Topa, G. The Implementation of a Remote Work Program in an Italian Municipality before COVID-19: Suggestions to HR Officers for the Post–COVID-19 Era. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollast, R.; Schmitz, M.; Bigot, A.; Luminet, O. The Theory of Planned Behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison of health behaviors between Belgian and French residents. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Guy, C.; Héroux, M.; Lichtfouse, E.; An, C. The impact of successive COVID-19 lockdowns on people mobility, lockdown efficiency, and municipal solid waste. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3959–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski-Maaser, I.; Graversgaard, M.; Foster, N.; Prutzer, M.; Roest, A.H.; Boogaard, F. WaterCoG: Evidence on How the Use of Tools, Knowledge, and Process Design Can Improve Water Co–Governance. Water 2021, 13, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronvang, B.; Wendland, F.; Kovar, K.; Fraters, D. Land Use and Water Quality. Water 2020, 12, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, X.; Shao, G.; Hu, T. Effects of Land Use on Stream Water Quality in the Rapidly Urbanized Areas: A Multiscale Analysis. Water 2020, 12, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woda na Świecie: Wyzwania Lokalne i Globalne. Available online: https://www.avk.com.pl/pl–pl/nowosci/aktualnosci–avk/woda–na–swiecie (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Di Crosta, A.; Ceccato, I.; Marchetti, D.; La Malva, P.; Maiella, R.; Cannito, L.; Cipi, M.; Mammarella, N.; Palumbo, R.; Verrocchio, M.C.; et al. Psychological factors and consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bakar, H.; Williams, L.; Hallett, S.H. Quantifying the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on household water consumption patterns in England. Npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakchan, A.; Roy, A.; Faust, K.M. Impacts of COVID-19 social distancing policies on water demand: A population dynamics perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 15, 113949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlament Europejski: Parlament Przyjął Porozumienie o Czystości Wody Pitnej i Odpadach Plastikowych. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/pl/press–room/20201211IPR93619/parlament–przyjal–porozumienie–o–czystosci–wody–pitnej–i–odpadach–plastikowych (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Ober, J.; Karwot, J. Tap Water Quality: Seasonal User Surveys in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawęska, K.; Bawiec, A.; Włodek, S.; Smaga, E. Wstępna analiza średniego zużycia wody w jednorodzinnych gospodarstwach domowych. Infrastrukt. I Ekol. Teren. Wiej. 2013, 1, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Foryś, I.; Machała, S.W. Zużycie wody w gospodarstwach domowych na przykładzie Spółdzielni Mieszkaniowej “Ogrodnik”w Sianowie. Stud. I Pr. Wydziału Nauk. Ekon. I Zarządzania US 2016, 45, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne+Nagel: Raport Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Kuehne+Nagel w Polsce za 2020 Rok. Available online: https://pl.kuehne–nagel.com/–/raport–zrownowazonego–rozwoju–2020 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Kuzior, A.; Postrzednik-Lotko, K.A.; Postrzednik, S. Limiting of Carbon Dioxide Emissions through Rational Management of Pro-Ecological Activities in the Context of CSR Assumptions. Energies 2022, 15, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Wolniak, R. Sharing Economies’ Initiatives in Municipal Authorities’ Perspective: Research Evidence from Poland in the Context of Smart Cities’ Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M.; Bindzár, P. Assessing the Level of Renewable Energy Development in the European Union Member States. A 10–Year Perspective. Energies 2021, 14, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek–Kotzur, I. Cognitive Technologies—Are We in Danger of Humanizing Machines and Dehumanizing Humans? Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2022, 30, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koronawirus: Informacje i Zalecenia. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Rybnik. O mieście. Available online: https://www.rybnik.eu/miasto/o-miescie (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Rybnik. Available online: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rybnik (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedyńska, S.; Książek, M. Statystyczny Drogowskaz 3. Praktyczny Przewodnik Wykorzystania Modeli Regresji Oraz Równań Strukturalnych; Sedno: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Calculation for the Sobel Test. Available online: http://quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Bera, A.; Das, S.; Pani, A.; Bera, B.; Shit, P.K. Assessment of household water consumption during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional web-based study in India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira Campos, M.A.; Carvalhoa, S.L.; Kurotusch Melo, S.; Gonçalves, G.B.F.R.; dos Santos, J.R.; Barros, R.L.; Morgado, U.T.M.A.; da Silva Lopes, E.; Reis, R.P.A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on water consumption behaviour. Water Supply 2021, 21, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, M.; Tran, D. The Impact of COVID-19 on Urban Water Consumption in the United States. Water 2022, 14, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Mańka-Szulik, M.; Krawczyk, D. Changes in the management of electronic public services in the metropolis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 24, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Krawczyk, D.; Brożek, P.; Pakhnenko, O.; Vasylieva, T.; Lyeonov, S. Resilience of Smart Cities to the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, G.; Apio, C.; Han, K.; Goo, T.; Chung, H.W.; Kim, T.; Kim, H.; Ko, Y.; Lee, D.; Lim, J.; et al. Statistical Estimation of Effects of Implemented Government Policies on COVID-19 Situation in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Alshazly, H.; Idris, S.A.; Bourouis, S. Evaluating the Impact of COVID-19 on Society, Environment, Economy, and Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Stand. Dev. | Median (Q25–Q75) | Min.–Max. | Confidence Interval | Stand. Error | ||

| −95.00% | +95.00% | |||||

| New cases (in thousands) | 167.61 ± 217.14 | 24.14 (10.61–271.22) | 2.31–644.09 | 55.97 | 279.25 | 52.66 |

| Deaths | 4394.88 ± 4942.76 | 1188 (400–8258) | 33–14,250 | 1853.55 | 6936.22 | 1198.80 |

| Quarantine (in thousands) | 4977.09 ± 3308.71 | 3298.26 (2776.1–6343.66) | 1094.3–11,679.16 | 3275.90 | 6678.27 | 802.48 |

| Descriptive Statistics—Water Consumption (in m³) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Stand. Dev. | Median (Q25–Q75) | Min.–Max. | Confidence Interval | Stand. Error | ||

| −95.00% | +95.00% | |||||

| Residential buildings (in thousands) | 221.73 ± 22.1 | 213.46 (202.51–238.62) | 196.46–271.92 | 210.37 | 233.09 | 5.36 |

| Collective housing buildings (in thousands) | 133.01 ± 5.07 | 131.9 (130.56–134.92) | 123.7–144 | 130.40 | 135.61 | 1.23 |

| Dwellings (in thousands) | 15.09 ± 0.57 | 14.97 (14.82–15.21) | 14.45–16.57 | 14.80 | 15.38 | 0.14 |

| Households (in thousands) | 369.82 ± 22.97 | 365.77 (350.58–388.69) | 334.92–417.28 | 358.02 | 381.63 | 5.57 |

| Descriptive Statistics—Water Consumption (in m3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Stand. Dev. | Median (Q25–Q75) | Min.–Max. | Confidence Interval | Stand. Error | ||

| −95.00% | +95.00% | |||||

| Industry (in thousands) | 52.29 ± 6.24 | 51.29 (48.87–55.09) | 44.64–71.18 | 49.08 | 55.50 | 1.51 |

| Trade (in thousands) | 10.11 ± 1.15 | 9.9 (9.63–10.81) | 8.13–12.45 | 9.52 | 10.71 | 0.28 |

| Services (in thousands) | 14.37 ± 3.55 | 13.59 (11.74–15.69) | 10.58–22.08 | 12.55 | 16.20 | 0.86 |

| Business sector (in thousands) | 76.77 ± 10.36 | 74.15 (70.09–79.92) | 64.39–105.54 | 71.45 | 82.10 | 2.51 |

| Descriptive Statistics—Water Consumption (in m3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Stand. Dev. | Median (Q25–Q75) | Min.–Max. | Confidence Interval | Stand. Error | ||

| −95.00% | +95.00% | |||||

| Schools (in thousands) | 2.97 ± 1.34 | 3.19 (1.86–3.59) | 1.04–5.44 | 2.28 | 3.66 | 0.32 |

| Kindergartens (in thousands) | 1.3 ± 0.64 | 1.45 (0.72–1.91) | 0.13–2.02 | 0.97 | 1.62 | 0.16 |

| Other government and local government institutions (in thousands) | 6.25 ± 1.79 | 6.15 (4.7–7.11) | 4.54–10.45 | 5.33 | 7.17 | 0.43 |

| Government and local government institutions (in thousands) | 10.52 ± 2.74 | 9.58 (9.01–11.61) | 5.84–16.88 | 9.11 | 11.93 | 0.67 |

| Variables | Pearson’s Linear Correlation Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| New Cases | Deaths | Quarantine | |

| Residential buildings | r = −0.592; p < 0.05 | r = −0.534; p < 0.05 | r = −0.531; p < 0.05 |

| Collective housing buildings | r = 22120.025; p = 0.923 | r = 0.061; p = 0.817 | r = 0.028; p = 0.916 |

| Dwellings | r = 0.026; p = 0.921 | r = 0.174; p = 0.505 | r = 0.062; p = 0.814 |

| Households | r = −0.574; p < 0.05 | r = −0.496; p < 0.05 | r = −0.503; p < 0.05 |

| Industry | r = −0.201; p = 0.439 | r = −0.283; p = 0.271 | r = −0.097; p = 0.71 |

| Trade | r = −0.351; p = 0.167 | r = −0.403; p = 0.109 | r = −0.368; p = 0.146 |

| Services | r = −0.525; p < 0.05 | r = −0.59; p < 0.05 | r = −0.5; p < 0.05 |

| Business sector | r = −0.341; p = 0.181 | r = −0.418; p < 0.095 | r = −0.271; p = 0.292 |

| Schools | r = 0.182; p = 0.483 | r = 0.088; p = 0.737 | r = 0.169; p = 0.518 |

| Kindergartens | r = 0.435; p < 0.081 | r = 0.427; p < 0.087 | r = 0.369; p = 0.145 |

| Other government and local government institutions | r = −0.436; p < 0.08 | r = −0.498; p < 0.05 | r = −0.394; p = 0.118 |

| Government and local government institutions | r = −0.094; p = 0.719 | r = −0.182; p = 0.485 | r = −0.089; p = 0.735 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficient | Non-Standardized Coefficient. | T | p | Test F | R2corr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | Stand. Error | B | Stand. Error | ||||||

| Residential buildings | New cases (c) | −0.59 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −2.84 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 8.08; p < 0.05 | 0.31 |

| New cases (c′) | −0.28 | 0.20 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.41 | p = 0.179 | F(2.14) = 10.85; p < 0.01 | 0.55 | |

| Services (b) | 0.60 | 0.20 | 3.71 | 1.22 | 3.03 | p < 0.01 | |||

| Households | New cases (c) | −0.57 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −2.72 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 7.37; p < 0.05 | 0.28 |

| New cases (c′) | −0.35 | 0.23 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −1.51 | p = 0.153 | F(2.14) = 6.09; p < 0.05 | 0.39 | |

| Services (b) | 0.43 | 0.23 | 2.80 | 1.48 | 1.88 | p < 0.08 | |||

| Services | New cases (a) | −0.53 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.39 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.71; p < 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficient | Non–Standardized Coefficient | t | p | Test F | R2corr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Stand. Error | B | Stand. Error | ||||||

| Residential buildings | Deaths (c) | −0.53 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.45 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.98; p < 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Deaths (c′) | −0.15 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.67 | p = 0.511 | F(2.14) = 9.13; p < 0.01 | 0.50 | |

| Services (b) | 0.66 | 0.22 | 4.08 | 1.36 | 3.01 | p < 0.01 | |||

| Households | Deaths (c) | −0.50 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.21 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 4.89; p < 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Deaths (c′) | −0.20 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.80 | p = 0.436 | F(2.14) = 4.77; p < 0.05 | 0.32 | |

| Services (b) | 0.49 | 0.26 | 3.20 | 1.65 | 1.94 | p < 0.073 | |||

| Services | Deaths (a) | −0.59 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.83 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 8; p < 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficient | Non–Standardized Coefficient | t | p | Test F | R2corr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Stand. Error | B | Stand. Error | ||||||

| Residential buildings | Quarantine (c) | −0.53 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.43 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.89; p < 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Quarantine (c′) | −0.21 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.07 | p = 0.302 | F(2.14) = 9.9; p < 0.01 | 0.53 | |

| Services (b) | 0.64 | 0.20 | 3.96 | 1.24 | 3.20 | p < 0.01 | |||

| Households | Quarantine (c) | −0.50 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.26 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.09; p < 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Quarantine (c′) | −0.26 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.12 | p = 0.282 | F(2.14) = 5.27; p < 0.05 | 0.35 | |

| Services (b) | 0.48 | 0.23 | 3.13 | 1.51 | 2.08 | p < 0.057 | |||

| Services | Quarantine (a) | −0.50 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.24 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.01; p < 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficient | Non–Standardized Coefficient | t | p | Test F | R2corr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Stand. Error | B | Stand. Error | ||||||

| Services | New cases (c) | −0.53 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.39 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.71; p < 0.05 | 0.23 |

| New cases (c′) | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.91 | p < 0.076 | F(2.14) = 133.58; p < 0.001 | 0.94 | |

| Other government and local government institutions (b) | 0.91 | 0.07 | 1.81 | 0.13 | 13.77 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Other government and local government institutions | New cases (a) | −0.44 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.88 | p < 0.08 | F(1.15) = 3.53; p < 0.08 | 0.14 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficient | Non–Standardized Coefficient | t | p | Test F | R2corr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Stand. Error | B | Stand. Error | ||||||

| Services | Deaths (c) | −0.59 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.83 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 8; p < 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Deaths (c′) | −0.14 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.14 | p < 0.05 | F(2.14) = 141.04; p < 0.001 | 0.95 | |

| Other government and local government institutions (b) | 0.90 | 0.07 | 1.78 | 0.13 | 13.38 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Other government and local government institutions | Deaths (a) | −0.50 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.22 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 4.93; p < 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficient | Non–Standardized Coefficient | t | p | Test F | R2corr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | Stand. Error | B | Stand. Error | ||||||

| Services | Quarantine (c) | –0.50 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.24 | p < 0.05 | F(1.15) = 5.01; p < 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Quarantine (c′) | −0.14 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.25 | p < 0.05 | F(2.14) = 144.87; p < 0.001 | 0.95 | |

| Other government and local government institutions (b) | 0.91 | 0.06 | 1.81 | 0.12 | 14.62 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Other government and local government institutions | Quarantine (a) | −0.39 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.66 | p = 0.118 | F(1.15) = 2.76; p = 0.118 | 0.10 |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Mediator | Pathways c/c′ | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New cases | Residential buildings | Services | β = −0.59; p < 0.05/ β = −0.28; p = 0.179 | Total |

| Deaths | Residential buildings | Services | β = −0.53; p < 0.05/ β = −0.15; p = 0.511 | Total |

| Quarantine | Residential buildings | Services | β = −0.53; p < 0.05/ β = −0.21; p = 0.302 | Total |

| Deaths | Services | Other government and local government institutions | β = −0.59; p < 0.05/ β = −0.14; p < 0.05 | Partial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ober, J.; Karwot, J. The Effect of Publicly Available COVID-19 Information on the Functioning of Society, Businesses, Government and Local Institutions: A Case Study from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032719

Ober J, Karwot J. The Effect of Publicly Available COVID-19 Information on the Functioning of Society, Businesses, Government and Local Institutions: A Case Study from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032719

Chicago/Turabian StyleOber, Józef, and Janusz Karwot. 2023. "The Effect of Publicly Available COVID-19 Information on the Functioning of Society, Businesses, Government and Local Institutions: A Case Study from Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032719