Abstract

Few studies have evaluated eating disorders in military personnel engaged in defense activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with eating disorders in military personnel from Lambayeque, Peru. A secondary data analysis was performed among 510 military personnel during the second epidemic wave of COVID-19 in Peru. We used the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) to assess eating disorders. We explored associations with insomnia, food insecurity, physical activity, resilience, fear to COVID-19, burnout syndrome, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and selected sociodemographic variables. Eating disorders were experienced by 10.2% of participants. A higher prevalence of eating disorders was associated with having 7 to 12 months (PR: 2.97; 95% CI: 1.24–7.11) and 19 months or more (PR: 2.62; 95% CI: 1.11–6.17) working in the first line of defense against COVID-19, fear of COVID-19 (PR: 2.20; 95% CI: 1.26–3.85), burnout syndrome (PR: 3.73; 95% CI: 1.90–7.33) and post-traumatic stress (PR: 2.97; 95% CI: 1.13–7.83). A low prevalence of eating disorders was found in the military personnel. However, prevention of this problem should be focused on at-risk groups that experience mental health burdens.

1. Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are conditions that alter eating habits [1], damaging physical-mental health and interpersonal relationships [2]. They manifest as anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN), among others [1,2]. There are several conditioning factors for the onset of ED in the military population, such as military-related trauma and exposure [3,4], post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and substance dependence (alcohol and tobacco) [5]. Worldwide, the estimated pre-pandemic prevalence of ED was 0.91%, particularly AN (0.16%), BN (0.63%) and binge eating disorder (BED) (1.93%), relatively lower than previously reported due to modifications in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnostic criteria [6]. In the military sector, significant prevalence figures ranging from 5 to 8% in women and 0.1% in men have been reported [7].

Following the impact of COVID-19 in physical and mental health [8,9,10,11], cases of ED increased due to social restrictions, dietary disturbances, sleep problems and difficulty in accessing medical care [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. To mitigate the effects of the pandemic, governments joined forces with the armed forces [21], a group highly vulnerable to behavioral problems due to COVID-19 [22]. Even before, binge eating (21.8%) had already been reported as the main ED, along with risk factors for developing ED due to the demanding weight regimen, such mental disorders (insomnia, anxiety, depression) and food insecurity [7]. In Peru, the military personnel supported the government lockdown measures as well as the immunization process [23]. Therefore, they were initially exposed to the mental health burden caused by the pandemic. There is, however, limited evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on their eating behaviors, as only the high prevalence of stressors such as nervousness and sadness, which could lead to mental problems, has been reported [24]. Such a scenario hinders the creation of preventive programs and early detection focused on personnel as part of the first line of defense against COVID-19.

Based on the above, the aim of the study is to explore the prevalence and factors associated with eating disorders in military personnel in the Lambayeque region during the COVID-19 health emergency, 2021.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population, and Sample

A secondary analysis of data generated from an analytic cross-sectional observational study was conducted to assess mental health in front-line military personnel in the face of COVID-19 during the second pandemic wave. The primary research was conducted from 2 to 9 November 2021 in the region of Lambayeque, Peru, a city heavily hit by the COVID-19 pandemic with high seroprevalence [25] and lethality [26].

The population for this investigation included 820 military personnel working in COVID-19 pandemic defense activities in the city of Lambayeque. In the primary study, a sample size of 582 individuals was estimated using an expected prevalence of 12.8% [27], 99% confidence level, precision of 2.5%, and adding 20% of the sample to compensate for possible participant losses and rejections. A higher number of participants (n = 710) than required was obtained, representing 86.6% of the study population. The final sample for this analysis included 550 military personnel. Sampling for the primary study was non-probability convenience sampling.

2.1.1. Instruments and Variables

- Eating Disorder symptomatology was the outcome, measured with the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26). This test consists of 26 self-report questions assessing general eating behavior and 5 additional questions assessing risk behaviors [28,29,30]. EAT-26 allows the detection of probable eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder [31]. Each question has 6 response options with different scoring: 0 points (never, rarely, sometimes); 1 point (often); 2 points (very often); 3 points (always) [28,29]. The total score is the sum of the responses to the 26 items, with question 26 being scored inversely. The higher the score, the higher the risk of anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN) [28,29]. The instrument has 3 subscales: (a) diet, with 13 items on avoidance of fattening foods and concerns about thinness; (b) bulimia and food preoccupation, with 6 items on bulimic behaviors and thoughts about food; and c) oral control, with 7 items on self-control of intake and external pressure to gain weight [28,29]. We used the Spanish version of EAT-26 validated by Gandarillas et al. [32]. The instrument used (EAT-26) has 88.9% sensitivity and 97.7% specificity [33]. The EAT-26 is a useful instrument for assessing risk of eating disorder, but it does not provide a definitive diagnosis [34]. A score of 20 or more obtained from the EAT-26 was considered as positive eating disorder symptomatology, which requires further clinical evaluation by mental health professionals [35]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93.

- Insomnia was measured with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). It consists of seven self-report items that measure the perceived severity of insomnia through a Likert-type scale from 0 to 4 points and a final score from 0 to 28 points. Higher scores reflect a greater degree of insomnia, with a cut-off point of 8 points [36]. It has been validated in older adults [37] and the general Spanish-speaking population [38]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.88.

- Food Insecurity was measured with the Household Food Insecurity Assessment Scale (HFIAS). It consists of nine items on a Likert scale of 1 to 3 points (1, seldom; 2, sometimes; 3, frequently). It has excellent psychometric properties in the Latin American population [39]. It has three domains: (1) anxiety and uncertainty about food supply in the household, (2) food quality and insufficient food intake and (3) physical consequences [39]. Mild IA has a score of 2–3 on the first item, 1–3 on the second item or 1 on the third or fourth item [39]. Moderate IA is defined as a score of 2–3 on the third or fourth item, or 1–2 on the fifth or sixth item [39]. Severe IA is defined as a score of 3 on the fifth or sixth item, or 1–3 on factors seven and eight and nine [39]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.87.

- Physical Activity was measured with the short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-S). This questionnaire includes 9 items and assesses reported physical activity during the last 7 days. It allows obtaining a weighted estimate of total physical activity from the activities reported per week to classify physical activity into: intense, moderate, mild or inactive [40]. It has been validated in Hispanic communities and applied to Latin American populations [41]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.64.

- Resilience was measured with the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). This questionnaire consists of 10 questions with a Likert scale of 0–4 points (0 “not at all”, 1 “rarely”, 2 “sometimes”, 3 “often”, 4 “almost always”) [42]. It presents adequate internal consistency and validity in multiple occupational groups, health personnel and general adult populations [43,44,45]. It uses a score of less than 30 to define high resilience and less than 30 for low resilience [42,43,44,45]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.97.

- Fear of COVID-19 was measured with the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. This questionnaire consists of 7 items with a Likert scale of 1–5 points (1 “strongly disagree”, 2 “disagree”, 3 “neither agree nor disagree”, 4 “agree”, 5 “strongly agree”) that evaluate the degree of fear of COVID-19, whereby a higher score indicates a greater fear of COVID-19 [46]. It has excellent psychometric properties and is considered a solid instrument for evaluation in different languages [47]. It has been validated in Latin and Spanish-speaking populations [48,49]. A cut-off point of 16.5 points has been validated to define fear of COVID [50]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.94.

- Burnout Syndrome was measured with the Maslach Burnout Inventory. It consists of 22 items with a Likert scale of 0–7 points organized in three dimensions that evaluate emotional exhaustion (9 items), depersonalization (5 items) and personal fulfillment (8 items) [51]. It has been validated in the Latin population [52] with adequate validity and reliability properties (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.87; sensitivity, 86.6%; specificity, 89%) [53]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.91.

- Anxiety was measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale (GAD-7). This instrument consists of 7 questions with a Likert scale of 0–3 points (0 “no day”, 1 “several days”, 2 “more than half of the days, 3 “almost every day”) [54]. It assesses anxiety symptoms during the prior 2 weeks, according to DSM-IV criteria [55]. Scores are grouped into no anxiety (0–4 points), mild anxiety (5–9 points), moderate anxiety (10–14 points) and severe anxiety (15–21 points). Its psychometric properties are optimal (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.93; sensitivity, 86.8%; and specificity, 93.4%) [54]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93.

- Depression was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): This questionnaire evaluates the presence of depressive symptoms during the prior 2 weeks and is based on DSM-IV criteria [56]. It presents 9 items and uses a Likert scale from 0 to 3 points to evaluate four response options (0 “never”, 1 “several days”, 2 “more than half of the days”, 3 “almost every day”) and has a final score range between 0 to 27 points. It has been validated in the Peruvian population and shows excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.87) [57]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.92.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder was measured with the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C): This instrument is made up of 17 questions with a Likert scale of 1–5, which measure symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, based on the DSM-IV criteria and the rubric of the National Center for PTSD [58,59]. It comprises the domains of trauma re-experiencing (domain B), trauma avoidance and blunting (domain C) and hyperactivity (domain D) [58,59]. It presents a score from 17 to 85 points, with 43 points being the cut-off point to define PTSD [58,59]. It has been validated in Latin populations [60], demonstrating adequate psychometric properties in its internal validity [59]. In the military population, it has been found to have adequate internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity [61]. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.95.

- General, occupational and psychosocial data: age in years, gender (male, female), single marital status (no, yes), religion (none, Catholic, non-Catholic), children (no, yes), report of frequent alcohol and tobacco consumption (no, yes), report of comorbidities (arterial hypertension, diabetes), body mass index (underweight, normal, overweight, obese), work time (1 to 6 months, 7 to 12 months, 13 to 18 months, 19 months or more), reported personal prior mental health history (no, yes), reported family prior mental health history (no, yes), sought help for mental health problem during COVID pandemic (no, yes), reliance on government to handle COVID (no, yes).

2.1.2. Procedures

A request was sent to the military authority in Lambayeque, Peru, to interview in person the military personnel who were working in the first line of defense against the COVID-19 health emergency. We used a questionnaire designed in REDCap, a data entry system that allowed us to capture data with optimal quality control. After obtaining the authorization from the ethics committee and military authority, the organization to conduct the study began among the research team. The interviews were scheduled in three groups in two shifts (morning and afternoon), under the supervision of the officer in charge and the research team. The soldiers were gathered in ventilated environments, always ensuring the social distance between each one, hand sanitization with alcohol and mandatory use of masks. The supervisor distributed the questionnaire through a link sent to coordination groups of participating soldiers. Prior to accessing the questionnaires, the participants had to voluntarily agree to participate by means of the electronic informed consent form inserted in the first part of the link. Each military member was autonomous to participate in the study and was not obliged by their superior coordinators to answer the questionnaire.

2.1.3. Statistical Analysis

We downloaded the database from the REDCap data entry system and imported it into Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

In the descriptive analysis, we report absolute and relative frequencies of categorical variables. For numerical variables, we reported the best measure of central tendency and dispersion, after evaluating normal distribution.

We performed bivariate analysis between the outcome (eating disorder symptoms) and covariates, using the chi-square test after evaluating the expected frequency assumption.

We estimated crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) to explore factors associated with eating disorder symptoms. We used generalized linear Poisson family models with log link function to construct simple and multiple regression models. In the multiple regression model, we included variables whose p-value was statistically significant (p < 0.05) in the simple model. We evaluated collinearity between the covariates of interest.

2.1.4. Ethical Aspects

Authorization was obtained from Universidad San Martin de Porres to conduct the primary research. The database was anonymized, preserving the confidentiality and anonymity of the military participants. Informed consent was requested, and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were respected

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

In the primary study, 86.6% of the population was enrolled (n = 710), including military personnel actively working in response to COVID-19 and who gave their consent to participate in the study. For this analysis, military personnel who responded to the EAT-26 questionnaire were considered and 160 military personnel who did not respond to the variables of interest were excluded.

Of 550 participants, 95.5% were male and the median age was 22 years. Frequent consumption of alcohol and tobacco was reported by 17.6% and 6.7%, respectively. Arterial hypertension was reported by 9.6%, and 33.6% reported being overweight. Labor time was reported more frequently around 19 months or more (36.9%). Around a third of participants (33.6%) had overweight and 6.8% obesity. Almost half of participants (48.7%) suffered from food insecurity and 11.6% reported low physical activity. Burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder were experienced by 9.3% and 7.5% of participants, respectively. Regarding mental health outcomes, 19.2% experienced fear of COVID-19, while 14% and 7.5% had suicidal risk and post-traumatic stress disorder, respectively. Additionally, 10.2% of the military presented eating disorder symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n = 550).

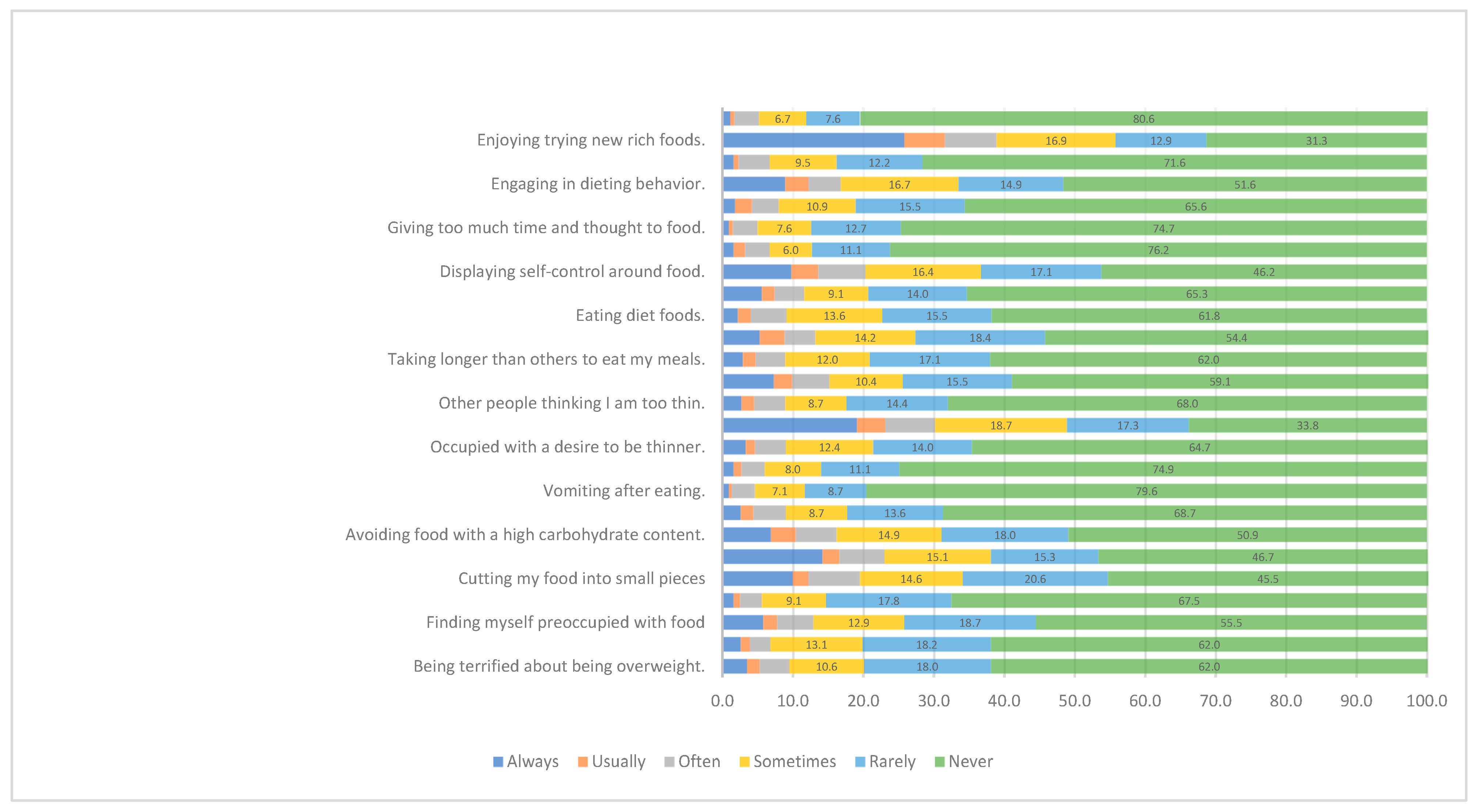

In addition, 19.1% of participants reported that they always exercise a lot to burn calories, 14.2% reported that they always consider the calories in the food they eat, and 10% cut their food into small pieces (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses from the Eating Attitudes Test-26.

3.2. Factors Associated with Eating Disorder Symptoms

Labor time (p = 0.022), insomnia (p < 0.001), fear of COVID-19 (p < 0.001) and burnout syndrome (p = 0.005) were found to be significantly associated with eating disorder symptoms. Additionally, military members with depressive (p = 0.009) and anxious (p < 0.001) symptoms had a higher frequency of eating disorder symptoms. Military members with post-traumatic stress disorder had a higher frequency of eating disorder symptoms than those who did not suffer from this mental disorder (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with eating disorder symptoms in bivariate analysis.

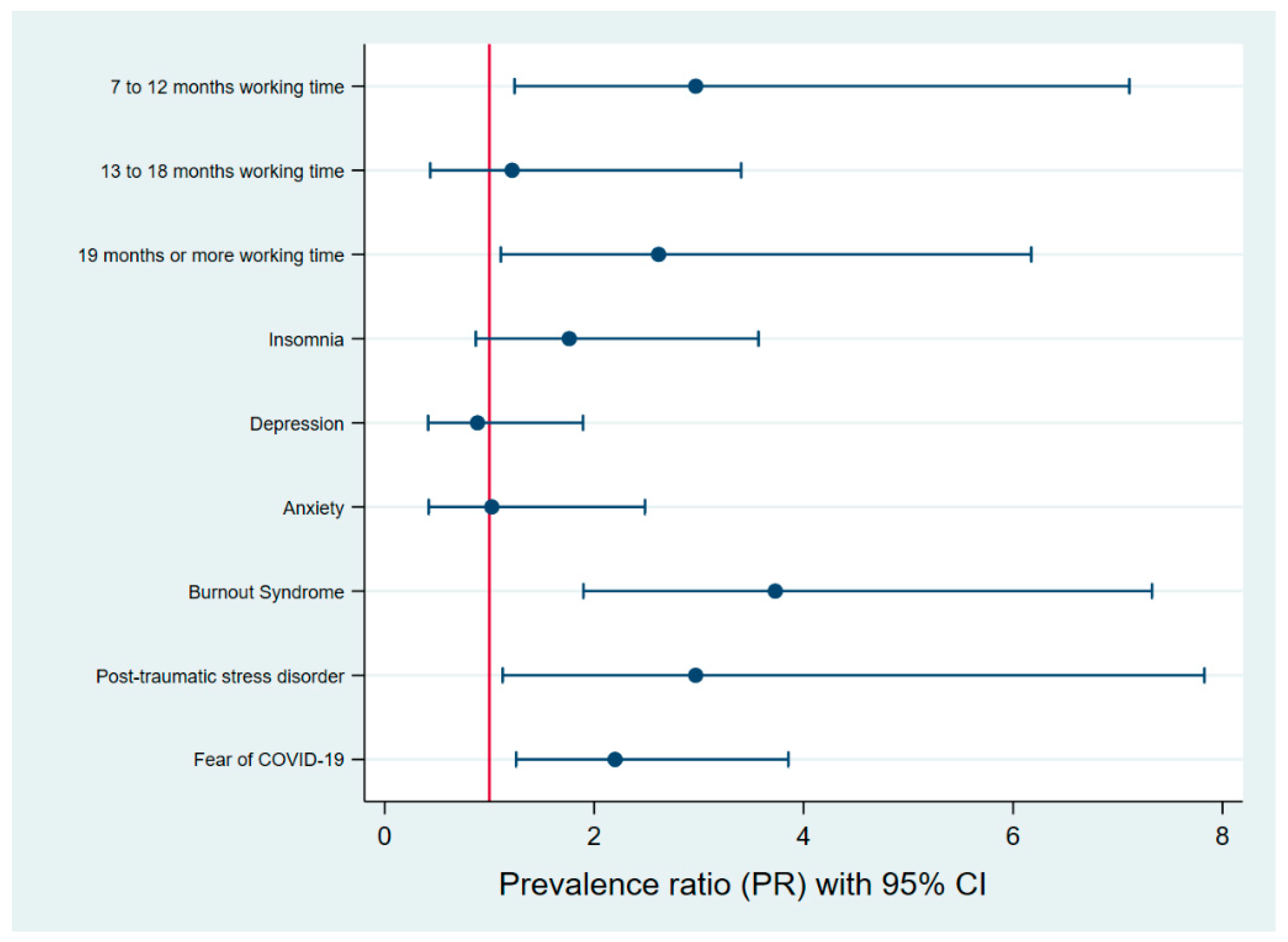

3.3. Factors Associated with Eating Disorder Symptoms in Simple and Multiple Regression Analysis

In the simple model (Table 3), the factors associated with a higher prevalence of eating disorder symptoms were working time, insomnia (PR: 2.71; CI 95%: 1.67–4.42), fear of COVID (PR: 3.36; CI 95%: 2.05–5.49), presenting burnout syndrome (PR: 2.39; CI 95%: 1.32–4.33), anxiety (PR: 2.50; CI 95%: 1.53–4.09), depression (PR: 1.91; PR: 1.17–3.14) and post-traumatic stress (PR: 4.14; CI 95%: 2.47–6.92) (Table 3). In the multiple regression model, we found that military personnel with work time between 7 to 12 months and 19 months or more had 197% (PR: 2.97; CI 95%: 1.24–7.11) and 162% (PR: 2.62; CI 95%: 1.11–6.17) higher prevalence of eating disorder symptoms, respectively. Fear of COVID increased the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms by 120% (PR: 2.20; CI 95%: 1.26–3.85) Additionally, military members with burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder presented 273% (PR: 3.73; CI 95%: 1.90–7.33) and 197% (PR: 2.97; CI 95%: 1.13–7.83) higher prevalence of eating disorder symptoms, respectively (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Factors associated with eating disorder symptoms in military first line of defense against COVID-19 in Lambayeque, Peru in simple and multiple regression analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the factors associated with eating behavior in multiple regression analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

Factors associated with a higher prevalence of ED were being at work 19 months longer in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, fear of COVID-19, having burnout syndrome and having PTSD. Additionally, factors that were not associated with EDs were insomnia, anxiety and depression.

4.2. Prevalence of Eating Disorder Symptoms

We found that 1 in 10 military personnel presented eating disorder symptoms (10.2%). This finding is similar to that reported by Masheb et al. in US military veterans in 2021, where 32.8% of women and 18.8% of men evidenced symptoms consistent with a DSM-5 eating disorder diagnosis [62]. In a similar study in a population of military veterans in the United States in 2021, Mitchell et al. found a prevalence of eating disorders ranging from 9.9% to 27.7% [5]. The prevalence found could be explained by the high rates of psychological trauma they face in their military service; strict physical fitness requirements and weight standards; the possibility of being exposed to or witnessing violence; fear of death, dying, and harm to self or others during combat; killing during combat; and changes in eating behavior during service [4,7].

4.3. Factors Associated with Eating Disorder Symptoms

Being in service more than 18 months or longer in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic increased the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. This is similar to that reported by Górska et al. in 2021, where the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on residents of Europe, Australia, and North and South America increased the prevalence of eating disorders in people who were working [63]. This finding could be explained by the fact that prolonged hours of work on the public road may cause eating disorders because of the military human resource gap in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic [63].

Military personnel with fear of COVID-19 significantly increased the prevalence of conduct disordered eating. Rodgers et al. assert that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in eating disorders, as fear of COVID-19 transmission has led individuals to experience increased concerns regarding food quality or its ability to be a vehicle for transmission and disruptions in daily routines and activity restrictions have negatively impacted eating and exercise patterns [13]. Fernandez-Aranda et al. reported that confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertainty of becoming infected, has generated in people restrictions in their daily activities, changing their lifestyles and having an impact on the significant increase in eating disorders [64]. This finding could be explained by the fear of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 through food, due to the high rate of transmission and mortality resulting from COVID-19 disease evidenced during the second pandemic wave in our country [65,66].

We found that military members with burnout syndrome had a higher prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. This is similar to that reported by Özcan et al. in 2021 in Turkey, where having job burnout was associated with a higher frequency of eating disorders, causing higher consumption of fast food, infrequent exercise and higher alcohol consumption [67]. Likewise, Verhavert et al. reported that dietary behavior was positively associated with the risk of burnout syndrome generating in people the consumption of fast food and unhealthy food [68]. This finding could be explained by the fact that military personnel are under constant pressures and desires to optimize performance in their service and pressures to meet certain objectives with traits of compulsiveness and perfectionism, leading to burnout and generating eating disorders [69,70].

Having PTSD increased the prevalence of eating disorders symptoms. In a US study by Vaught et al. in military veterans in 2021, the prevalence of PTSD in patients with eating disorders was found to have a mean of 56.4 [71]. Forman-Hoffman, in 2012, reported in her study a prevalence of PTSD in female veterans with eating disorders of 18.6% [72]. This finding could be explained because PTSD and eating disorders share common symptoms such as emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and alexithymia [73], thus people with PTSD choose a higher intake of unhealthy foods and/or a lower intake of healthy foods generating an increase in eating disorders [74].

In the raw model, it was evidenced that having anxiety and depression is positively associated with eating disorder symptoms. However, this association was not maintained in the final model. This differs from what was reported by Elran-Barak et al. in their study conducted in adults from the Project on Implicit Mental Health (PIMH) website, who found a positive association between eating disorder and mental health (depression and anxiety), and 10.2% and 20.9% presented depressive and anxious symptoms, respectively [75]. This is different from that reported by Sander et al. who found that anxiety and depression were associated with a higher frequency of ED, and 81.1%, 16.6% and 12.5% of people had eating disorders, anxiety and depression, respectively [76]. This finding could be explained by interruptions in access to food and eating routines and movement and exercise restrictions causing a higher level of anxiety and depression in the population [77].

4.4. Public Health Implications of Findings

The international outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has led countries to implement drastic containment measures, suggesting an abrupt confinement of populations causing addiction-related habits, such as caloric/salty food intake [78]. Eating disorders are a public health problem, have high mortality rates and are among the most costly disorders to treat [7], thus bringing serious consequences for the psychological and physical health of the population [71]. However, little is known about the prevalence of such conditions in the military population [7]. In the face of the COVID-19 outbreak, the military were responsible for creating social distance, maintaining quarantine, disinfecting city streets, and establishing field hospitals, forming part of the first line of care against COVID-19 together with health personnel [79].

There are several potential risk factors for the development of ED among military service members, who may engage in disordered eating behaviors, including self-induced vomiting and taking laxatives, diuretics, and diet pills, in response to the strict physical fitness and weight standards imposed by the military [7].

Patients with eating disorders constitute a vulnerable population in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [80], which can be reduced by early and appropriate help-seeking; however, despite the availability of effective treatments, very few people with eating disorders seek treatment [81].

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

The study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow causality to be inferred. The second is nonresponse bias, as military personnel could experience very sensitive variation in the degree of motivation in their voluntary participation in the study, either by over- or under-reporting. The third is membership bias among study participants, where subgroups are present due to their hierarchical levels, which makes them share some attribute, which could be positively or negatively related to the outcomes. The fourth is information bias, since the variables were measured by self-report of the participants. In addition, the findings of this research should be interpreted with some caution given that the EAT-26 instrument provides risk assessment of eating disorder and not a definitive diagnosis; therefore it requires an evaluation by a medical professional [35,82]. Fifth, some variables such as race [5], sexual disorder (sexual harassment and assault) [83], addiction to social networks [35], self-esteem [35] and body satisfaction [35] could not be measured and would be associated with eating disorder, and this is because it is a secondary data analysis. The sixth is selection bias, since our population was entirely from the Lambayeque region; considering that there are many military personnel from other regions of Peru, our results could not be extrapolated to other regions due to systematic differences with our population. However, this study provides valuable information on the eating behavior of the military population when exposed to COVID-19; to our knowledge, it is the first evaluation of eating disorders in Peruvian military personnel during the pandemic. Therefore, the results obtained have been carefully inferred and written to draw conclusions that serve as background for future research.

5. Conclusions

Almost one out of ten participants experienced eating disorder symptoms. The factors associated with a higher prevalence of eating disorder symptoms were being at work 19 months before the COVID-19 pandemic, fear of getting COVID-19, having burnout syndrome, and having PTSD. Special attention should be given to these factors since the mental health burden of the pandemic may last longer for those vulnerable personnel. This information would be of value for local military institutions and provide feedback for future research in this topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.V.-G.; Formal analysis, M.J.V.-G. and V.E.F.-R.; Investigation, M.J.V.-G., D.A.L.-F., C.K.P.-R. and A.G.-V.; Methodology, M.J.V.-G., D.A.L.-F., C.K.P.-R. and A.G.-V.; Project administration, M.J.V.-G.; Resources, M.J.V.-G.; Software, M.J.V.-G.; Supervision, M.J.V.-G.; Validation, D.V.-G., V.E.F.-R. and C.J.P.-V.; Visualization, D.V.-G., V.E.F.-R. and C.J.P.-V.; Writing–original draft, D.A.L.-F., C.K.P.-R., A.G.-V. and V.E.F.-R.; Writing–review and editing, M.J.V.-G., D.A.L.-F., C.K.P.-R., A.G.-V., D.V.-G., V.E.F.-R. and C.J.P.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The primary study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad San Martin de Porres.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available because the ethics committee has not provided permission/authorization to publicly share the data, but the data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

M.J.V.-G. was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) under Award Number D43TW009343 and the University of California Global Health Institute (UCGHI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Psychiatry.Org—What Are Eating Disorders? Available online: https://psychiatry.org:443/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Balasundaram, P.; Santhanam, P. Eating Disorders. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arditte Hall, K.A.; Bartlett, B.A.; Iverson, K.M.; Mitchell, K.S. Military-Related Trauma Is Associated with Eating Disorder Symptoms in Male Veterans. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 1328–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arditte Hall, K.A.; Bartlett, B.A.; Iverson, K.M.; Mitchell, K.S. Eating Disorder Symptoms in Female Veterans: The Role of Childhood, Adult, and Military Trauma Exposure. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2018, 10, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.S.; Masheb, R.; Smith, B.N.; Kehle-Forbes, S.; Hardin, S.; Vogt, D. Eating Disorder Measures in a Sample of Military Veterans: A Focus on Gender, Age, and Race/Ethnicity. Psychol. Assess. 2021, 33, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An Update on the Prevalence of Eating Disorders in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, B.A.; Mitchell, K.S. Eating Disorders in Military and Veteran Men and Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhuapoma-Yance, M.; Apolaya-Segura, M.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Díaz-Vélez, C. Human development and COVID-19 lethality rate: Ecological study in America. Rev. Cuerpo Med. Hosp. HNAAA 2021, 14, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Elera, L.E.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Martinez-Rivera, R.N.; Morocho-Alburqueque, N.; Temoche-Rivas, M.S.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Self-Medication in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Peru. Germs 2022, 12, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Jiménez, F.; Vives-Kufoy, C.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Mortalidad En Pacientes Hospitalizados Por COVID-19. Estudio Prospectivo En El Norte Del Perú, 2020. Rev. Méd. Chile 2021, 149, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, V.V.; Garrido, M.V.; Peralta, C.I.; Astudillo, D.; Malca, J.T.; Manrique, E.O.; Quispe, E.T. Factores Asociados al Afrontamiento Psicológico Frente a La COVID-19 Durante El Periodo de Cuarentena. Rev. Cub. Med. Mil. 2020, 49, 0200870. [Google Scholar]

- Changes of Symptoms of Eating Disorders (ED) and Their Related Psychological Health Issues during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis|J Eat Dis|Full Text. Available online: https://jeatdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40337-022-00550-9 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Linardon, J.; Courtet, P.; Guillaume, S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Eating Disorder Risk and Symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P. Eating Disorders in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Have We Learned? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenas, I.; Etxandi, M.; Munguía, L.; Granero, R.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Sánchez, I.; Ortega, E.; Andreu, A.; Moize, V.L.; Fernández-Real, J.-M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown in Eating Disorders: A Multicentre Collaborative International Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Picón-Reátegui, C.K.; Zila-Velasque, J.P.; Grados-Espinoza, P. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Insomnia in Military Personnel: A Retrospective Study during the Second COVID-19 Epidemic Wave in Peru. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Milano, W.D.; Carpinelli, L. Eating Disorders (EDs) and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study on the Impact of Phase II of the Lockdown. BioMed 2022, 2, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, C.R.; Liendo-Venegas, D.; García-Gamboa, F.; Mejía-Rodríguez, M.A.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Factors Associated with the Perception of Inadequate Sanitary Control in 12 Latin American Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 934087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiak, P.S.; Adamczyk, N.; Jodczyk, A.M.; Kaproń, A.; Lisowska, A.; Mamcarz, A.; Śliż, D. COVID-19 Pandemic Consequences among Individuals with Eating Disorders on a Clinical Sample in Poland—A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, B.; Bray, C.; Bradley, R.; Zwickey, H. Binge Eating Disorder Is a Social Justice Issue: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Study of Binge Eating Disorder Experts’ Opinions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Pan American Health Organization. Impact of COVID-19 on Human Resources for Health and Policy Response: The Case of Plurinational State of Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: Overview of Findings from Five Latin American Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003900-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bouskill, K.E.; Fitzke, R.E.; Saba, S.K.; Ring, C.; Davis, J.P.; Lee, D.S.; Pedersen, E.R. Stress and Coping among Post-9/11 Veterans During COVID-19: A Qualitative Exploration. J. Vet. Stud. 2022, 8, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las Fuerzas Armadas del Perú y su lucha contra la COVID-19. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/ccffaa/informes-publicaciones/2049105-las-fuerzas-armadas-del-peru-y-su-lucha-contra-la-covid-19 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- The Effects of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of the Peruvian Police and Armed Forces. Available online: https://www.ejgm.co.uk/article/the-effects-of-covid-19-on-the-mental-health-of-the-peruvian-police-and-armed-forces-10839 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Díaz-Vélez, C.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Colchado, J.; Carrera-Acosta, L.; Becerra, M.; Paico, D.M.; Ocampo-Salazar, E.T. SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence Study in Lambayeque, Peru. June–July 2020. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Vélez, C.; Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Romero-Cerdán, A.; Peña-Sánchez, E.R.; Fernández Mogollon, J.L.; Cossio Chafloque, J.D.; Marreros Ascoy, G.C.; Benites-Zapata, V.A. Risk Factors for Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 from Three Hospitals in Peru: A Retrospective Cohort Study. F1000Research 2021, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Tsai, J.; Southwick, S.M. Association of Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With Posttraumatic Psychological Growth Among US Veterans During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e214972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constaín, G.A.; Ricardo Ramírez, C.; Rodríguez-Gázquez, M.d.L.Á.; Alvarez Gómez, M.; Marín Múnera, C.; Agudelo Acosta, C. Diagnostic validity and usefulness of the Eating Attitudes Test-26 for the assessment of eating disorders risk in a Colombian female population. Aten. Primaria 2014, 46, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constaín, G.A.; Rodríguez-Gázquez, M.d.L.Á.; Ramírez Jiménez, G.A.; Gómez Vásquez, G.M.; Mejía Cardona, L.; Cardona Vélez, J. Diagnostic validity and usefulness of the Eating Attitudes Test-26 for the assessment of eating disorders risk in a Colombian male population. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noma, S.; Nakai, Y.; Hamagaki, S.; Uehara, M.; Hayashi, A.; Hayashi, T. Comparison between the SCOFF Questionnaire and the Eating Attitudes Test in Patients with Eating Disorders. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2006, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26). Available online: https://novopsych.com.au/assessments/diagnosis/eating-attitudes-test-26-eat-26/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Trastornos del Comportamiento Alimentario: Prevalencia de Casos en Mujeres Adolescentes de la Comunidad de Madrid. Available online: https://psiquiatria.com/trastornos_de_alimentacion/trastornos-del-comportamiento-alimentario-prevalencia-de-casos-en-mujeres-adolescentes-de-la-comunidad-de-madrid/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Jacobi, C.; Hayward, C.; de Zwaan, M.; Kraemer, H.C.; Agras, W.S. Coming to Terms with Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Application of Risk Terminology and Suggestions for a General Taxonomy. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 19–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jumayan, A.A.; Al-Eid, N.A.; AlShamlan, N.A.; AlOmar, R.S. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Eating Disorders in Patrons of Sport Centers in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2021, 28, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Martinez, P.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J.; Martinez-Jimenez, M.P.; Redel-Macías, M.D.; Pagliari, C.; Vaquero-Abellan, M. Social Media, Thin-Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes: An Exploratory Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an Outcome Measure for Insomnia Research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.C.; Guillén-Serrano, V.; Santos-Iglesias, P. Insomnia Severity Index: Some indicators about its reliability and validity on an older adults sample. Rev. Neurol. 2008, 47, 566–570. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, A.; Vela-Bueno, A.; Olavarrieta-Bernardino, S.; Calhoun, S.L.; Bixler, E.O.; Vgontzas, A.N. The Spanish Version of the Insomnia Severity Index: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide|Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA). Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/monitoring-and-evaluation/household-food-insecurity-access-scale-hfias (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Mantilla Toloza, S.C.; Gómez-Conesa, A. El Cuestionario Internacional de Actividad Física. Un instrumento adecuado en el seguimiento de la actividad física poblacional. Rev. Iberoam. Fisioter. Kinesiol. 2007, 10, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela Carral, J.M.; Lago Ballesteros, J.; Ayán Pérez, C.; Mosquera Morono, M.B. Análisis de Fiabilidad y Validez de Tres Cuestionarios de Autoinforme Para Valorar La Actividad Física Realizada Por Adolescentes Españoles. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M.B. Psychometric Analysis and Refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-Item Measure of Resilience. J. Trauma. Stress 2007, 20, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, V.; Guisande, M.A.; Sánchez, M.T.; Otero, P.; Vázquez, F.L. Spanish Validation of the 10-Item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10) with Non-Professional Caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler Sánchez, M.I.; Meseguer de Pedro, M.; García Izquierdo, M. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de la escala de resiliencia de 10 ítems de Connor-Davidson (CD-RISC 10) en una muestra multiocupacional. Rev. Latinoam. De Psicol. 2016, 48, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notario-Pacheco, B.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Serrano-Parra, M.D.; Bartolomé-Gutiérrez, R.; García-Campayo, J.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Reliability and Validity of the Spanish Version of the 10-Item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-Item CD-RISC) in Young Adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2011, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Lin, C.-Y.; Ullah, I.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. Item Response Theory Analysis of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S): A Systematic Review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarcaya-Victoria, J.; Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Podestà, A.; Luna-Cuadros, M.A. Psychometric Properties of a Spanish Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in General Population of Lima, Peru. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorca, M.; Martínez-Lorca, A.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Armesilla, M.D.C.; Latorre, J.M. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Validation in Spanish University Students. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikopoulou, V.A.; Holeva, V.; Parlapani, E.; Karamouzi, P.; Voitsidis, P.; Porfyri, G.N.; Blekas, A.; Papigkioti, K.; Patsiala, S.; Diakogiannis, I. Mental Health Screening for COVID-19: A Proposed Cutoff Score for the Greek Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confiabilidad y Validez Factorial Del Maslach Burnout Inventory Versión Human Services Survey En Una Muestra de Asistentes Sociales Chilenos. Available online: https://www.psicologiacientifica.com/maslach-burnout-inventory-confiabilidad/ (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Validación Del Cuestionario Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS) En Contexto Académico Colombiano*. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2011-30802016000100002 (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Millán de Lange, A.C.; D’Aubeterre López, M.E. Propiedades Psicométricas Del Maslach Burnout Inventory-GS En Una Muestra Multiocupacional Venezolana. Rev. Psicol. (PUCP) 2012, 30, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Campayo, J.; Zamorano, E.; Ruiz, M.A.; Pardo, A.; Pérez-Páramo, M.; López-Gómez, V.; Freire, O.; Rejas, J. Cultural Adaptation into Spanish of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale as a Screening Tool. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Jimenez, R.A.; Nuñez-Magallanes, A.; Franco-Jimenez, R.A.; Nuñez-Magallanes, A. Propiedades Psicométricas Del GAD-7, GAD-2 y GAD-Mini En Universitarios Peruanos. Propósitos Represent. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baader, M.T.; Molina, F.J.L.; Venezian, B.S.; Rojas, C.C.; Farías, S.R.; Fierro-Freixenet, C.; Backenstrass, M.; Mundt, C. Validación y Utilidad de La Encuesta PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) En El Diagnóstico de Depresión En Pacientes Usuarios de Atención Primaria En Chile. Rev. Chil. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2012, 50, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Copez-Lonzoy, A.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Bazo-Alvarez, J.C. Valid Group Comparisons Can Be Made with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A Measurement Invariance Study across Groups by Demographic Characteristics. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Bovin, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Sloan, D.M.; Schnurr, P.P.; Kaloupek, D.G.; Keane, T.M.; Marx, B.P. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation in Military Veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaye, B.; Zheng, Y.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Rondon, M.B.; Sánchez, S.E.; Williams, M.A. Validity of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) Checklist in Pregnant Women. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.N.V.; Marshall, G.N.; Schell, T.L. Spanish and English Versions of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C): Testing for Differential Item Functioning. J. Trauma. Stress 2008, 21, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, K.C.; Lang, A.J.; Norman, S.B. Synthesis of the Psychometric Properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Military, Civilian, and Specific Versions. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masheb, R.M.; Ramsey, C.M.; Marsh, A.G.; Decker, S.E.; Maguen, S.; Brandt, C.A.; Haskell, S.G. DSM-5 Eating Disorder Prevalence, Gender Differences, and Mental Health Associations in United States Military Veterans. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górska, P.; Górna, I.; Miechowicz, I.; Przysławski, J. Changes in Life Situations during the SARS-CoV-2 Virus Pandemic and Their Impact on Eating Behaviors for Residents of Europe, Australia as Well as North and South America. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Aranda, F.; Munguía, L.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Etxandi, M.; Baenas, I.; Granero, R.; Sánchez, I.; Ortega, E.; Andreu, A.; et al. COVID Isolation Eating Scale (CIES): Analysis of the Impact of Confinement in Eating Disorders and Obesity—A Collaborative International Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, N.L.; Matsangas, P. Eating Behaviors in Sailors of the United States Navy: Meal-to-Sleep Intervals. Nutr. Health 2021, 27, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Olavarría, D.; Latorre-Román, P.Á.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.P.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Delgado-Floody, P. Positive and Negative Changes in Food Habits, Physical Activity Patterns, and Weight Status during COVID-19 Confinement: Associated Factors in the Chilean Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, B.A.; Uslu, B.; Okudan, B.; Alphan, M.E. Evaluation of the Relationships between Burnout, Eating Behavior and Quality of Life in Academicans. Prog. Nutr. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhavert, Y.; De Martelaer, K.; Van Hoof, E.; Van Der Linden, E.; Zinzen, E.; Deliens, T. The Association between Energy Balance-Related Behavior and Burn-Out in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, E397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauder, T.D.; Williams, M.V.; Campbell, C.S.; Davis, G.D.; Sherman, R.A. Abnormal Eating Behaviors in Military Women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, T.W.; Isaksson Rø, K.; Rø, Ø. Burnout among Staff on Specialized Eating Disorder Units in Norway. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaught, A.S.; Piazza, V.; Raines, A.M. Prevalence of Eating Disorders and Comorbid Psychopathology in a US Sample of Treatment-Seeking Veterans. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman-Hoffman, V.L.; Mengeling, M.; Booth, B.M.; Torner, J.; Sadler, A.G. Eating Disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress, and Sexual Trauma in Women Veterans. Mil. Med. 2012, 177, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.M.; Pilcher, N.; Duka, T. Deter the Emotions: Alexithymia, Impulsivity and Their Relationship to Binge Drinking. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 12, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijkers, C.; Schoorl, M.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Eating Disorders and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elran-Barak, R.; Goldschmidt, A.B. Differences in Severity of Eating Disorder Symptoms between Adults with Depression and Adults with Anxiety. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.; Moessner, M.; Bauer, S. Depression, Anxiety and Eating Disorder-Related Impairment: Moderators in Female Adolescents and Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elran-Barak, R. Analyses of Posts Written in Online Eating Disorder and Depression/Anxiety Moderated Communities: Emotional and Informational Communication before and during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Internet Interv. 2021, 26, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, B.; Haesebaert, F.; Zante, E.; Benyamina, A.; Haesebaert, J.; Franck, N. Global Changes and Factors of Increase in Caloric/Salty Food Intake, Screen Use, and Substance Use During the Early COVID-19 Containment Phase in the General Population in France: Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, S.H.; Shahrezagamasaei, M.; Hatef, B.; Shahyad, S. Comparison of COVID-19 Anxiety, Health Anxiety, and Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in Militaries and Civilians during COVID-19 Outbreaks. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 9, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Huete Cordova, M.A. Trastorno de Conducta Alimentaria Durante La Pandemia Del SARS-CoV-2. Rev. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2022, 85, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Paxton, S.J. Mental Health First Aid for Eating Disorders: Pilot Evaluation of a Training Program for the Public. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interpretation—EAT-26: Eating Attitudes Test & Eating Disorder Testing. Available online: https://www.eat-26.com/interpretation/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Gewirtz-Meydan, A.; Spivak-Lavi, Z. Profiles of Sexual Disorders and Eating Disorder Symptoms: Associations With Body Image. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).