Developing a Healthy Environment Assessment Tool (HEAT) to Address Heat-Health Vulnerability in South African Towns in a Warming World

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

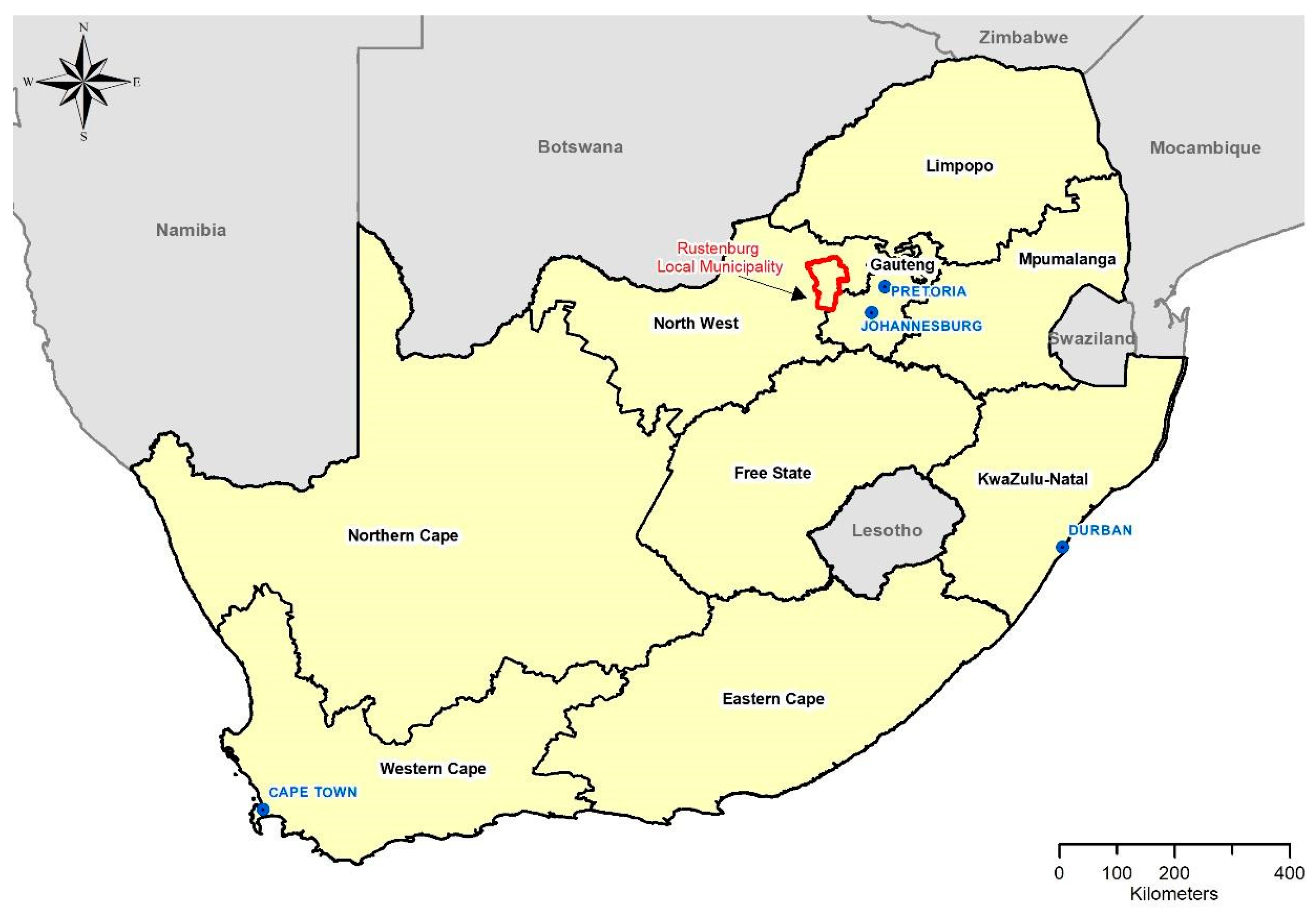

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Conceptual Heat-Health Risk Assessment Framework

2.3. The Integrated Development Plan

2.4. Stakeholder Workshop

2.5. Tool Development and Application

2.6. Calculation of Risk for Each Ward/Suburb

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Heat-Health Risk Profile for Wards/Suburbs in the Rustenburg Local Municipality

3.2. Developing Interventions and Actions to Reduce Heat-Health Vulnerabilities

3.3. Study Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lazenby, M.J.; Landman, W.A.; Garland, R.M.; DeWitt, D.G. Seasonal Temperature Prediction Skill over Southern Africa, and Human Health. Meteorol. Appl. 2014, 21, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.E.; Alexander, L.V. On the Measurement of Heat Waves. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 4500–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbokodo, I.; Bopape, M.-J.; Chikoore, H.; Engelbrecht, F.; Nethengwe, N. Heatwaves in the Future Warmer Climate of South Africa. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.Y.; Kapwata, T.; Wernecke, B.; Garland, R.M.; Nkosi, V.; Shezi, B.; Landman, W.A.; Mathee, A. Gathering the Evidence and Identifying Opportunities for Future Research in Climate, Heat and Health in South Africa: The Role of the South African Medical Research Council. S. Afr. Med. J. 2019, 109, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, R.M.; Matooane, M.; Engelbrecht, F.A.; Bopape, M.-J.M.; Landman, W.A.; Naidoo, M.; van der Merwe, J.; Wright, C.Y. Regional Projections of Extreme Apparent Temperature Days in Africa, and the Related Potential Risk to Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 12577–12604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quick Stats: Percentage Distribution of Heat-Related Deaths, by Age Group—National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2018–2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7124a6 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Marue, K. As Gauteng and Limpopo Brave Another Heat Wave, the Northern Cape’s Tshwaragano District Hospital Has Reported 17 Deaths from the Recent Heat Wave That Sent Temperatures Soaring. Available online: https://health-e.org.za/2016/02/04/northern-cape-heat-wave-claims-at-least-17/ (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Newsroom Fact Sheet: Climate Change Heat and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-heat-and-health (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Chung, J.-Y.; Honda, Y.; Hong, Y.-C.; Pan, X.-C.; Guo, Y.-L.; Kim, H. Ambient Temperature and Mortality: An International Study in Four Capital Cities of East Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 408, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.S.; Basu, R.; Malig, B.; Broadwin, R.; Kim, J.J.; Ostro, B. The Effect of Temperature on Hospital Admissions in Nine California Counties. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.A.; Matamale, L.; Kharidza, S.D. Impact of Climate Change on Children’s Health in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 831–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Department of Environment, Forestry & Fisheries. National Climate Change Response White Paper. 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/nationalclimatechangeresponsewhitepaper0.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Scovronick, N.; Sera, F.; Acquaotta, F.; Garzena, D.; Fratianni, S.; Wright, C.Y.; Gasparrini, A. The Association between Ambient Temperature and Mortality in South Africa: A Time-Series Analysis. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapwata, T.; Gebreslasie, M.; Scovronick, N.; Acquaotta, F.; Wright, C. Towards the Development of a Heat-Health Early Warning System for South Africa. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 3, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Ncongwane, K.P.; Botai, J.O.; Sivakumar, V.; Botai, C.M.; Adeola, A.M. Characteristics and Long-Term Trends of Heat Stress for South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathee, A.; Oba, J.; Rose, A. Climate Change Impacts on Working People (the HOTHAPS Initiative): Findings of the South African Pilot Study. Glob. Health Action 2010, 3, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichmann, J. Heat Effects of Ambient Apparent Temperature on All-Cause Mortality in Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg, South Africa: 2006–2010. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 587–588, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Environmental Affairs, Republic of South Africa. National Climate Change and Health Adaptation Plan 2014–2019. 2014. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/preventionweb/files/57216_nationalclimatechangeandhealthadapt.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Water, Air and Climate Change Bureau Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch. Adapting to Extreme Heat Events: Guidelines for Assessing Health Vulnerability; Canada. 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/reports-publications/climate-change-health/adapting-extreme-heat-events-guidelines-assessing-health-vulnerability-health-canada-2011.html (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Pradyumna, A.; Sankam, J. Tools and Methods for Assessing Health Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change: A Scoping Review. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2022, 8, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmi, O.V.; Hayden, M.H. Connecting People and Place: A New Framework for Reducing Urban Vulnerability to Extreme Heat. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environmental Affairs Long-Term Adaptation Scenarios Flagship Research Programme (LTAS) for South Africa. Climate Change Implications for Human Health in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa, 2013. Available online: https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/summary_policymakers_bookV3.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Mukheibir, P.; Ziervogel, G. Framework for Adaptation to Climate Change for the City of Cape Town—FAC4T (City of Cape Town). University of Cape Town, 2006. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/9700/06Mukheibir-Ziervoge_-_Adaptation_to_CC_in_Cape_Town.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Roberts, D. Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation and Local Level Resilience in Durban, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2010, 22, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalatse, L.; Mbara, G. Impacts of Climate Change and Vulnerable Communities at the City of Johannesburg. 2009. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8405019/IMPACTS_OF_CLIMATE_CHANGE_AND_VULNERABLE_COMMUNITIES_AT_THE_CITY_OF_JOHANNESBURG (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Rustenburg Local Municipality Rustenburg Integrated Development Plan 2012–2017. 2012. Available online: https://www.rustenburg.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/IDP-2017-2022-May-2017.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Rustenburg Local Municipality North-West Provincial Gazette No 5574. Northwest Prov. Gaz, 2000. Available online: https://www.rustenburg.gov.za/notices/provincial-gazette-notice/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. Statistics South Africa 2011 Census. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Protecting Health from Climate Change: Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/104200 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Health Canada. Adapting to Extreme Heat Events: Guidelines for Assessing Health Vulnerability. 2012. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/reports-publications/climate-change-health/adapting-extreme-heat-events-guidelines-assessing-health-vulnerability-health-canada-2011.html (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Teare, J.; Mathee, A.; Naicker, N.; Swanepoel, C.; Kapwata, T.; Balakrishna, Y.; du Preez, D.J.; Millar, D.A.; Wright, C.Y. Dwelling Characteristics Influence Indoor Temperature and May Pose Health Threats in LMICs. Ann. Glob. Heal. 2020, 86, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.Y.; Dominick, F.; Kapwata, T.; Bidassey-Manilal, S.; Engelbrecht, J.C.; Stich, H.; Mathee, A.; Matooane, M. Socio-Economic, Infrastructural and Health-Related Risk Factors Associated with Adverse Heat-Health Effects Reportedly Experienced during Hot Weather in South Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 34, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapwata, T.; Gebreslasie, M.T.; Mathee, A.; Wright, C.Y. Current and Potential Future Seasonal Trends of Indoor Dwelling Temperature and Likely Health Risks in Rural Southern Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSF-Health Meeting Report: Improving Health Preparedness for Extreme Heat Events in South Asia. In Proceedings of the 1st South Asia Climate Services Forum for Health (CSF-Health), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 26–28 April 2016; Available online: https://ghhin.org/wp-content/uploads/HEALTH_PREPAREDNESS_FOR_EXTREME_HEAT_EVE.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Linzalone, N.; Coi, A.; Lauriola, P.; Luise, D.; Pedone, A.; Romizi, R.; Sallese, D.; Bianchi, F.; HIA21 Project Working Group. Participatory health impact assessment used to support decision-making in waste management planning: A replicable experience from Italy. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Vulnerability indicators | Population was assessed by mention of “elderly”, “disabled”, or “crèches” in the IDP. |

| Poverty was estimated from the IDP by comments such as “high crime rate” and “high rates of unemployment” in each suburb. Areas with mention of makeshift housing and backyard dwellings were also considered low-income and classified as red; a mixture of dwelling types was yellow; and suburbs with established houses and suburbs were green. | |

| Resilience/adaptive capacity indicators | ‘Access to education’ was yellow or green for presence of schools in the suburb; green if there was mention of primary and secondary schools; and yellow if there was a mention of only one. |

| ‘Access to medical facilities’ was green if there were 24-h clinics; yellow if there were just the mention of clinics or mobile clinics or that they are being upgraded; red if there was overcrowding or a shortage of medicine identified for the suburb. | |

| ‘Water and sanitation’ were yellow if mentioned but not clarified in terms of functionality; green if it was stated to be ‘safe, clean drinking water’ or working sanitation, and red if there are complications such as water scarcity, leaking sewage lines etc. | |

| ‘Public transport’ was identified by considering if there was a mention of buses or a taxi rank, however classified as red if there was the presence of several of such public spaces which are high risk for heat-health impacts. | |

| ‘Recreational/community centres’ included sports facilities, community halls, libraries, youth centres etc.; if more than two facilities existed, it was green. If they existed but were noted as being rundown or less than two existed, it was yellow. | |

| ‘Green spaces’ applied where parks or green spaces were mentioned. Grazing land or open land was categorised as yellow. Some suburbs mentioned construction on available empty land, or a lack of green spaces and these suburbs were categorised as red. |

| Risk # Level | Population | Poverty | Education | Medical Facilities | Sanitation and Basic Services | Transport | Community Centres | Green Spaces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Elderly Disabled Crèches OR Unemployed | High crime rate Unemployment Need for RDP houses | Mobile clinic/clinic | Mention of any health threatening issue | Need for one: Youth centre Business centre/Community office park | No green space/empty available | ||

| Informal or indigenous housing data | High drop-out rate | Insufficient supplies | (Sewage blockages or leaks) | Sports facilities/ground Library | ||||

| Presence of migrants Classification of informal settlement | High rates of substance abuse | Community hall ORUpgrading any of the above | ||||||

| Medium | One of the following: | Mobile clinic | Provision of basic services but functionality not specified | One of the following: | Grazing/open land | |||

| RDP houses | Early learning centre | Ambulances | Mention of only one service (functional) | Scholar transport | Library Youth centre Business centre/Community office park | Parks to be upgraded or created | ||

| Primary school | Upgrades to clinics | Service to be upgraded or installed | Sports facilities/Ground Community hall | |||||

| High school FET * college | Upgrading of any of the above | |||||||

| Low | Private land | Two or more of the following: | Provision of functioning sanitation and services: | One or more: Youth centre Business centre | ||||

| Businesses | Early learning centre Primary school | Clinic OR 24-h clinic | Two or more services mentioned | Taxi rank | Community office park | Parks/green spaces | ||

| Shopping centres | High school | Sports facilities/ground library | ||||||

| FET college | Community hall |

| Ward No. | Suburb Names | Risk Score * (x) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phatsima, Boshoek, Mefenya, Rasimone, Boekenhoutfontein, Magokgwane | 1.7 |

| 2 | Chaneng, Robega | 1.9 |

| 3 | Bafokeng North Mine, Impala, Luka Mogono, Rathibedi | 1.6 |

| 4 | Luka, Phokeng-Windsor | 2.0 |

| 5 | Sigmena, Lemenong Kwa Kgale, Lemenong, Lenatong, Punodung | 1.8 |

| 6 | Phokeng (Tshwara-Kotokoto), Saron, Dithabaneng, Masosobane, Masosobane 2, Salema, Phokeng, Ntsweng and Pitso, Greenside and Riverside, Makgokgwane, Ratshufi, Rafredi, | NEI |

| 7 | Babuanja, Lefaragatlha | 1.7 |

| 8 | Geelhoutpark Extensions 6.9 and 4, Mountain Ridge, Tlhabane West | NEI |

| 9 | Tlhabane | 2.6 |

| 10 | Tlhabane, Foxlake, Lebone, North-Flight | 2.6 |

| 11 | Jabula Hostel, Yizo, Oukasie | 2.4 |

| 12 | Meriting | 1.4 |

| 13 | Tlhabane, Oukasie-Sidzumo, Motsatsi, Lebone up to Dikgabong, Foxlake, Rustenburg North—Benoni, Berry | 1.7 |

| 14, 15, 16, 17 | Geelhoutpark, Protea Park, Boo Dorp, Cashan 1,2,3, Safari Garden 2,3,5,8, Rustenburg North-Benoni to Impala, Cashan Protea Park | 1.5 |

| 18 | Rustenburg East and North | 1.8 |

| 19 | Paardekraal, Sunrise Park | 2.2 |

| 20 | Boitekong Ext 4 and 2 | 1.6 |

| 21 | Boitekong Ext | 1.2 |

| 22 | Kanana Hostel, Sunrise, Leshibidung, Mpho Khunou, Popo Molefe, Skeirlik, Mzanzi, Siza | 2.0 |

| 23 | Kanana, Mafike, Chachalaza | NEI |

| 24 | Freedom Park, Lemenong and Paardekraal Extension | 1.5 |

| 25 | Monnakato, Kopman, Rooikraal, Chaneng | 1.9 |

| 26 | Tananana, Tlaseng, Tsitsing, Maile Extension | 2.3 |

| 27 and 28 | Lethabong | 1.7 |

| 29 | Mabitse, Maumong, Barseba, Rankelenyane | 2.1 |

| 30 | Modikwe, Behtanie, Makolokwe | 2.0 |

| 31 | Marikana; Marikana Central Business district, Skierluk, Storm Huis, Swartkopies, Brampie Big House, Group Five, Burnely, Mahumapelo 1and2, Tlapa | 1.5 |

| 32 | Wagkraal, Suurplaat, Mmaditlhokwa, Marikana West, Retief, Mabomvaneng, Lapologang | 1.7 |

| 33 | Nkaneng; Bleskop Hostel; Ngawana Hotel | 1.2 |

| 34 | Mfidikoe, Zakhele, Entabeni Hostel, Bokamoso, Central Deep | 2.2 |

| 35 | Matebeleng, Ikemeleng, Thuane, Levus Bayer, Lekokjaneng, Bolane, Waterval | 2.0 |

| 36 | Cyferbuild, Boons, Breedsvlei, Naauwpoort, Modderfontein, Vlakdrift, Sandfontein, Dinie Estate, Sparkling Water, Molote, Mathopestad, Boshfontein | 1.8 |

| 37 | Jabula, Boitekong, Paardekraal, Sunrise Park, Sondela | 2.4 |

| 38 | Freedom Park, New Freedom Park | 2.0 |

| 39 | Ramotshanana | 1.8 |

| 40 | Boitekong, Chachalaza | 2.7 |

| 41 | Seraleng, Boitekong | 1.7 |

| 42 | Waterfall East | NEI |

| 43 | Jabula, Zinniaville, Karlienpark | 1.8 |

| 44 | Lekgalong, Ikageng, Serutube, Mafika, Mogajane, Lesung, Mosenthal, Marikana | 1.9 |

| 45 | Photsaneng, Thekwana, Nkaneng, Phula Mines, Karee Mines | 2.0 |

| Human Settlements | Taxi and Bus Ranks | Marketplaces | Schools | Parks, Sports Fields and Stadia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green building design | Existing taxi ranks | Remote areas | Cold, clean water to all | Athlete medical assessment |

| RDP housing | Increased shade | Use recyclable materials for structure and furniture | Green buildings, school competitions, school awards | Water fountains |

| Solar geysers | Cool coatings and non-heat absorbent material | Ventilation | Sunscreen for all learners and teachers | Provide sunscreen to athletes |

| Cross ventilation | Plant Trees | Subdivisions, e.g., food, arts and crafts | Harvest rainwater in Jo-Jo water storage tank | Installation of sprinklers at stadia and sports fields |

| Window size proportion to floor area | Water fountains in close proximity | Water-based recycling system | Heated/cooling floors and furniture | Careful location of stadia and sports fields |

| Orientation of windows | Mister sprays | Plant trees | Heat protection school uniforms | Water harvesting |

| High enough roofs (ventilation) | New taxi ranks | Public awareness campaigns | No hands water fountains | Adjusting to foreign environments |

| Use cool (also colour) roof materials | Dome type roofs | Licenses, permits | Indigenous and fruit/nut trees | No physical activity when hot and humid |

| Ceilings and insulation | Sufficient ventilation | Use gel-based stoves (clean cooking) data | No sweet drinks at school | |

| Light paint on walls | Awareness campaigns | |||

| Trees for each dwelling | Food garden, some produce sold to community | |||

| Communal swimming pool | Grey water harvesting | |||

| Give children trees to plant at home |

| Intervention | Indicators | Possible Sector(s) Responsible |

|---|---|---|

| Public Sector | ||

| Plant trees to replace those cut down to build houses |

| Treasury Health Social development Planning Parks and recreation Housing Public Works |

| Provide water fountains in parks and taxi ranks | ||

| Covered waiting areas at bus and taxi ranks | ||

| Communal taps in streets to serve villagers | ||

| Reduce queues and waiting times in clinics and SASSA pay points | Number of learners and elderly who faint—SASSA pay points | |

| Amendment and drafting of by-laws to address climate change | Funds allocated to preventative health | |

| Provide public swimming pools in parks and schools | Number of swimming pools—student performance | |

Proper planning

| Learners at schools | |

| Private Sector | ||

| Hot weather education and awareness campaigns | Lifestyle surveys (epidemiology to conduct) | NGOs and CBOs |

| Enforcement of cutting trees (stop), stopping veld fires and other activities contribute to air pollution/climate change | Advocacy campaigns—through IDP training and awareness programmes for environmental health | |

| Social mobility—people should be removed from high-risk areas to lower risk areas | Number of greening projects | |

| Insulation of corrugated iron houses or concrete with corrugated iron roofs by lining with cardboard | Improved and approved infrastructure—EHPs should approve | |

| Adequate space between shacks | ||

| Staff rotation to reduce duration of exposure | Mining and industry | |

| Introduction of flexible shifts to reduce exposure to heat (early morning—3:00 a.m. until 8 a.m. ) | ||

| Mines to rehabilitate mining areas and provide parks/greening, shade, swimming pools and other appropriate interventions as part of their corporate social responsibility programmes | ||

| Compliance to building plans—natural, e.g., installation of airbricks to circulate air and artificial ventilation | ||

| Remain indoors, plant trees outdoors for shade/Use sunscreen or umbrellas, wear hats | Individual | |

| Wear breathable fabrics and light-coloured clothing because darker colours absorb heat | ||

| Hydrate regularly by drinking enough water | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wright, C.Y.; Mathee, A.; Goldstone, C.; Naidoo, N.; Kapwata, T.; Wernecke, B.; Kunene, Z.; Millar, D.A. Developing a Healthy Environment Assessment Tool (HEAT) to Address Heat-Health Vulnerability in South African Towns in a Warming World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042852

Wright CY, Mathee A, Goldstone C, Naidoo N, Kapwata T, Wernecke B, Kunene Z, Millar DA. Developing a Healthy Environment Assessment Tool (HEAT) to Address Heat-Health Vulnerability in South African Towns in a Warming World. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042852

Chicago/Turabian StyleWright, Caradee Y., Angela Mathee, Cheryl Goldstone, Natasha Naidoo, Thandi Kapwata, Bianca Wernecke, Zamantimande Kunene, and Danielle A. Millar. 2023. "Developing a Healthy Environment Assessment Tool (HEAT) to Address Heat-Health Vulnerability in South African Towns in a Warming World" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042852

APA StyleWright, C. Y., Mathee, A., Goldstone, C., Naidoo, N., Kapwata, T., Wernecke, B., Kunene, Z., & Millar, D. A. (2023). Developing a Healthy Environment Assessment Tool (HEAT) to Address Heat-Health Vulnerability in South African Towns in a Warming World. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042852