Crisis, What Crisis? The Effect of Economic Crises on Spending on Online and Offline Gambling in Spain: Implications for Preventing Gambling Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hypotheses

- The two economic crises reduced spending on gambling, although differences will be evident among the different types of gambling in terms of the relationship between GDP and spending thereon.

- The measures taken to reduce access to gambling venues, to curb the spread of SARS-CoV-2, will cause a reduction in spending on offline games but will not affect spending on online gambling.

2.2. Analysis

2.3. Procedure

- Directorate General for the Regulation of Gambling (DGOJ), Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Government of Spain, to obtain online gambling data and historic offline gambling data [38].

- National Institute of Statistics (INE), an autonomous institution of the Government of Spain, to obtain GDP data [39].

- Spanish Gaming Business Confederation (CEJUEGO), a business organization integrated within the State Confederation of Business Organizations (CEOE), which is the main organization representing large companies in Spain [40], to obtain recent offline gambling data.

3. Results

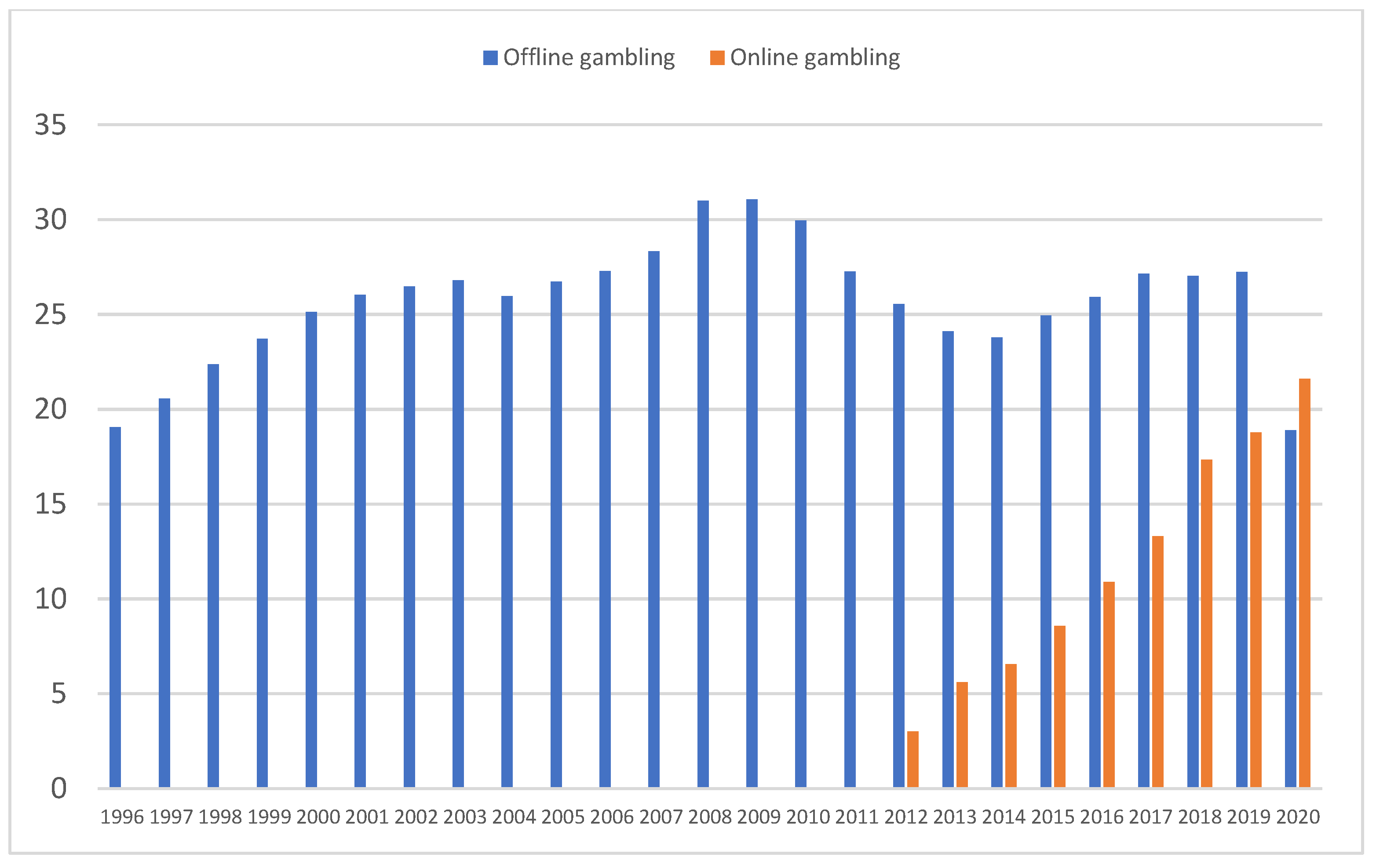

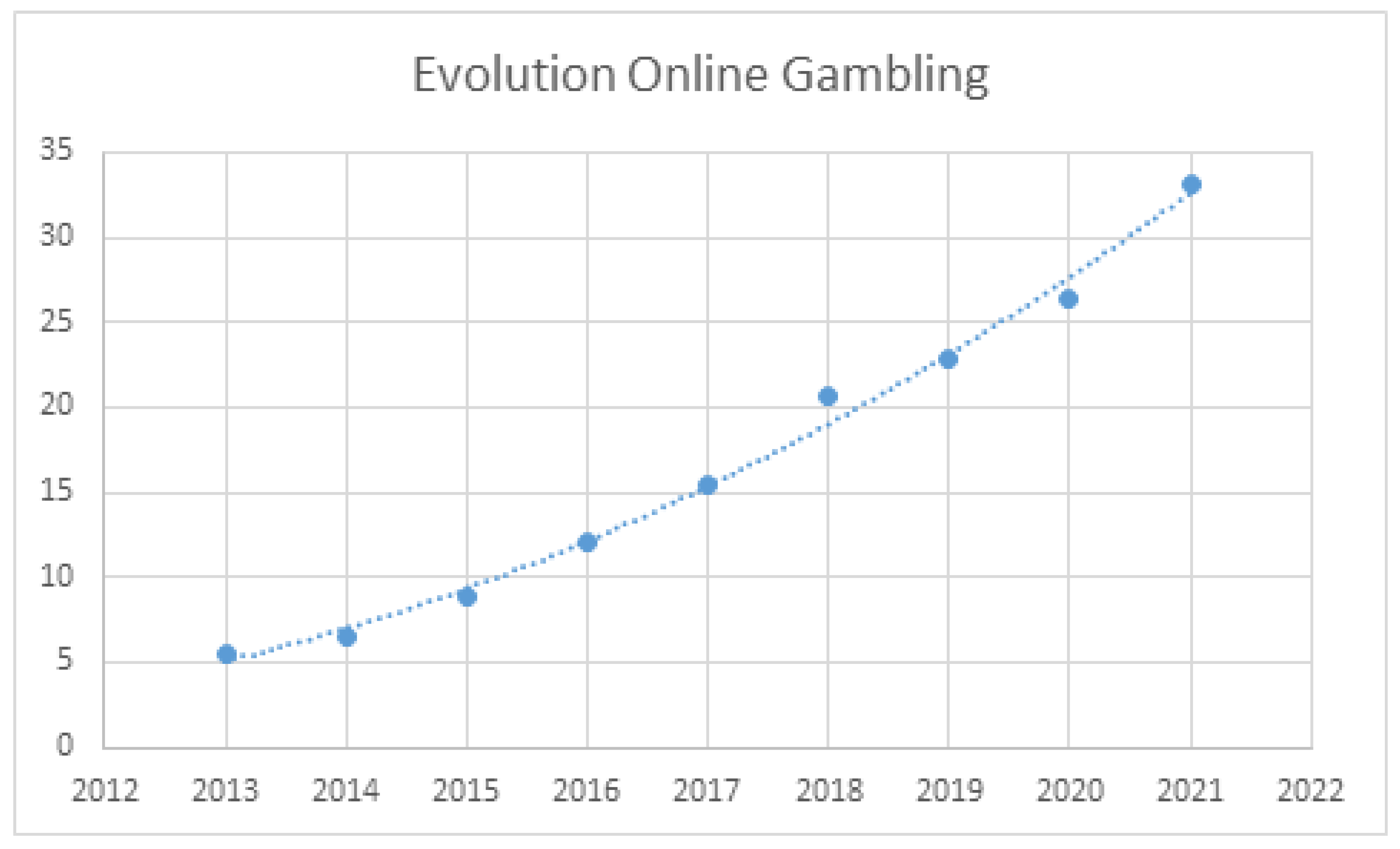

3.1. Global Spending on Traditional (Offline) Gambling and Online Gambling

3.2. Spending on the Different Types of Gambling

3.2.1. Evolution of Spending on Different Games between the 2008 Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2.2. Relationship between Spending on Different Games and GDP

- Offline gambling

- Offline gambling

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schwartz, D.G. Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling; Gotham Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin, K.; Barber, B. Not so doomed: Computer game play and positive adolescent development. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 23, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, E.A.; Meyers, L.S. The role of video game playing in adolescent life: Is there reason to be concerned? Bull. Psychon. Soc. 1984, 22, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spapens, T.; Littler, A.; Fijnaut, C. Crime, Addiction and the Regulation of Gambling; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, R. Vicious Games: Capitalism and Gambling (Anthropology, Culture and Society); Pluto Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, D.A.; Shaffer, H.J. Gambling and the health of the public: Adopting a public health perspective. J. Gambl. Stud. 1999, 15, 289–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.; Hilbrecht, M.; Billi, R. Charting a path towards a public health approach for gambling harm prevention. J. Public Health 2021, 29, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egerer, M.; Marionneau, V.; Nikkinen, J. Gambling Policies in European Welfare States; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chóliz, M. Ethical gambling: A necessary new point of view of gambling in public health policies. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Gross Gaming Revenue (GGR) as a Share of GDP in Select European Countries 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/967875/gross-gambling-revenue-share-gdp-europe-by-country (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Brosowski, T.; Hayer, T.; Meyer, G.; Rumpf, H.-J.; John, U.; Bischof, A. Thresholds of probable problematic gambling involvement for the German population: Results of the pathological gambling and epidemiology (PAGE) study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2015, 29, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, S.R.; Miller, N.V.; Hodgins, D.C.; Wang, J. Defining a threshold of harm from gambling for population health surveillance research. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2009, 9, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, I.; Kairouz, S.; Costes, J.M.; Weißmüller, K.S. Gambling spending and its concentration on problem gamblers. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, J.; Griffiths, M. The role of structural characteristics in gambling. In Research and Measurement Issues in Gambling Studies, 1st ed.; Smith, G., Hodgins, D.C., Williams, Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 217–249. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.J.; West, B.L.; Simpson, R.I. Prevention of Problem Gambling: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence and Identified Best Practices; Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Gross Gaming Revenue (GGR) Online and Offline in Europe from 2003 to 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1058386/online-and-offline-gross-gambling-revenue-europe (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Chóliz, M.; Mazón, M. The effect of the economic crisis on gambling spending [El efecto de la crisis económica sobre el gasto en juego de azar]. Inf. Psicológica 2013, 101, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- European State Lotteries and Toto Association. European Lotteries’ Report on Lotteries in the EU and in Europe in 2011, Lausanne. 2012. Available online: https://docplayer.net/13956270-European-lotteries-report-on-lotteries-in-the-eu-and-in-europe-in-2011.html (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Meitz, S.; Lotteries Performance in Times of Financial Crisis. Lotteries Performance in Times of Financial Crisis. The Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference for PhD Students and Young Scientists. 1 December 2013. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2372437 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Lyons, C.A. Gambling in the public marketplace: Adaptations to economic context. Psychol. Rec. 2013, 63, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, C.; Paap, R. The effect of recessions on gambling expenditures. J. Gambl. Stud. 2012, 28, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakins, J. Household gambling expenditures and the Irish recession. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 16, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olason, D.T.; Hayer, T.; Brosowski, T.; Meyer, G. Gambling in the mist of economic crisis: Results from three national prevalence studies from Iceland. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015, 31, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olason, D.T.; Hayer, T.; Meyer, G.; Brosowski, T. Economic recession affects gambling participation but not problematic gambling: Results from a population-based follow-up study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auer, M.; Malischnig, D.; Griffiths, M.D. Gambling before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among European regular sports bettors: An empirical study using behavioral tracking data. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainsbury, S.M.; Swanton, T.B.; Burgess, M.T.; Blaszczynski, A. Impacts of the COVID-19 shutdown on gambling patterns in Australia: Consideration of problem gambling and psychological distress. J. Addict. Med. 2021, 15, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A. Online gambling in the midst of COVID-19: A nexus of mental health concerns, substance use and financial stress. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 2022, 20, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, D.C.; Stevens, R.M. The impact of COVID-19 on gambling and gambling disorder: Emerging data. Curr. Opin. Psychiatr. 2021, 34, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Regan, M.; Pearce-Smith, N.; Sarfo-Annin, J.; Clark, R. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gambling Behaviour and Associated Harms: A Rapid Review; Public Health England: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, M.; Souliotis, K.; Malliori, M.; Peppou, L.E.; Kontoangelos, K.; Lazaratou, H.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Golna, C.; Dimitriadis, G.; Papadimitriou, G.; et al. Problem gambling in Greece: Prevalence and risk factors during the financial crisis. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019, 35, 1193–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, B.; Balazs, H.; Arnold, P.; Paksi, B.; Demetrovics, Z. Gambling in Western and Eastern Europe: The example of Hungary. J. Gambl. Stud. 2012, 28, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orford, J.; Wardle, H.; Griffiths, M.; Sproston, K.; Erens, B. The role of social factors in gambling: Evidence from the 2007 British Gambling Prevalence Survey. Community Work. Fam. 2010, 13, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schissel, B. Betting against youth: The effects of socioeconomic marginality on gambling among young people. Youth Soc. 2001, 32, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, H.J.; LaBrie, R.A.; LaPlante, D.A.; Nelson, S.E.; Stanton, M.V. The road less travelled: Moving from distribution to determinants in the study of gambling epidemiology. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2004, 49, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welte, J.W.; Barnes, G.M.; Wieczorek, W.F.; Tidwell, M.C.O.; Parker, J.C. Risk factors for pathological gambling. Addict. Behav. 2004, 29, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiansson, C. Pathways to excessive gambling within the social community construct. Gambl. Res. J. Natl. Assoc. Gambl. Stud. 2006, 18, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J.B.; Degenhardt, L.; Farrell, M. Excessive gambling and gaming: Addictive disorders? Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGOJ [Directorate General for the Regulation of Gambling]. Activity Report 2021. Available online: https://www.ordenacionjuego.es/en/actividad (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- INE [National Institute of Statistics]. Quarterly National Accounts of Spain: Main Aggregates. (QNA). Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736164439&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576581 (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Gómez, J.A.; Lalanda, C. Yearbook of Gambling in Spain, 2021 [Anuario del Juego en España 2021]; Instituto de Política y Gobernanza, Universidad Carlos III: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Borio, C. The COVID-19 economic crisis: Dangerously unique. Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Paulson, K.R.; Pease, S.A.; Watson, S.; Comfort, H.; Zheng, P.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Bisignano, C.; Barber, R.M.; Alam, T.; et al. Estimating Excess Mortality due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Análisis of COVID-19-Related Mortality, 2020–2021. Lancet 2022, 399, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on mental health. Progr. Neurol. Psychiatry 2020, 24, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Bhullar, N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int. J. Mental Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, A. Changes in gambling behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic—A web survey study in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvía, R. Lotteries: A Study from the New Economic Sociology [Loterías: Un Estudio Desde la Nueva Sociología Económica]; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, N.; Smith, D.; Thomas, T. Electronic gaming machines: Are they the ‘crack-cocaine’ of gambling? Addiction 2005, 100, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüll, N.D. Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.J.; Wood, R.T. The proportion of Ontario gambling revenue derived from problem gamblers. Can. Public Policy 2007, 33, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Wood, R.T. What Proportion of Gambling Revenue is Derived from Problem Gamblers? In Proceedings of the Alberta Gambling Research Institute Conference, Banff, AB, Canada, 7–9 April 2016.

- Chóliz, M. The challenge of online gambling: The effect of legalization on the increase in online gambling addiction. J. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 32, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capacci, S.; Randon, E.; Scorcu, A.E. Are Consumers More Willing to Invest in Luck During Recessions? Ital. Econ. J. 2017, 3, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chóliz, M.; Marcos, M.; Lázaro-Mateo, J. The risk of online gambling: A study of gambling disorder prevalence rates in Spain. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 2021, 19, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SELAE [State Society Lotteries and State Betting]. Annual Accounts and Management Report for the Year Ended 31 December 2020; SELAE: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.J. What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chóliz, M.; Saiz-Ruiz, J. Regulating gambling to prevent addiction: More necessary now than ever. Adicciones 2016, 28, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| Offline | 19.05 | 20.55 | 22.37 | 23.71 | 25.13 | 26.04 | 26.47 | 26.80 | 25.96 | 26.73 | 27.29 | 28.33 | 30.99 |

| Online | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 19.05 | 20.55 | 22.37 | 23.71 | 25.13 | 26.04 | 26.47 | 26.80 | 25.96 | 26.73 | 27.29 | 28.33 | 30.99 |

| GDP | 489.2 | 519.3 | 556.0 | 595.7 | 647.9 | 701.0 | 749.6 | 802.3 | 859.4 | 927.4 | 1003.8 | 1075.5 | 1109.5 |

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

| Offline | 31.06 | 29.96 | 27.25 | 25.55 | 24.11 | 23.79 | 24.94 | 25.91 | 27.15 | 27.02 | 27.24 | 18.88 | |

| Online | - | - | - | 3.00 | 5.56 | 6.51 | 8.87 | 12.00 | 15.43 | 20.58 | 22.85 | 26.40 | |

| Total | 31.06 | 29.96 | 27.25 | 28.55 | 29.70 | 30.35 | 33.50 | 36.80 | 40.45 | 44.35 | 46.02 | 40.48 | |

| GDP | 1069.3 | 1072.7 | 1063.8 | 1031.1 | 1020.3 | 1032.2 | 1077.6 | 1113.8 | 1161.9 | 1203.3 | 1244.4 | 1121.9 | |

| GDP | Lotteries * | Slot Machines * | Casino * | e-Poker | e-Sport Bet | e-Slot ** | e-Casino | Online Gambling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 489.2 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 4.6 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1997 | 519.3 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 4.8 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1998 | 556.0 | 8.1 | 8.8 | 4.9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1999 | 595.7 | 8.5 | 9.6 | 5.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2000 | 647.9 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 5.4 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2001 | 701.0 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 5.4 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2002 | 749.6 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 5.6 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2003 | 802.3 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 5.8 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2004 | 859.4 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 5.9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2005 | 927.4 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 6.3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2006 | 1003.8 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 6.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2007 | 1075.5 | 11.6 | 12.6 | 6.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2008 | 1109.5 | 11.6 | 14.5 | 5.7 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2009 | 1069.3 | 11.3 | 12.7 | 7.3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2010 | 1072.7 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 6.9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2011 | 1063.8 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 6.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2012 | 1031.1 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 5.5 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2013 | 1020.3 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | - | 1.3 | 5.6 |

| 2014 | 1032.2 | 9.9 | 8.5 | 5.6 | 2.1 | 2.9 | - | 1.5 | 6.5 |

| 2015 | 1077.6 | 10.3 | 8.8 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 8.9 |

| 2016 | 1113.8 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 6.6 | 1.6 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 12.0 |

| 2017 | 1161.9 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 15.4 |

| 2018 | 1203.3 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 20.6 |

| 2019 | 1244.4 | 11.2 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 2.2 | 6.9 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 22.8 |

| 2020 | 1121.9 | 9.1 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 26.4 |

| 2021 | 1205.1 | - | - | - | 2.4 | 10.5 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 33.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chóliz, M. Crisis, What Crisis? The Effect of Economic Crises on Spending on Online and Offline Gambling in Spain: Implications for Preventing Gambling Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042909

Chóliz M. Crisis, What Crisis? The Effect of Economic Crises on Spending on Online and Offline Gambling in Spain: Implications for Preventing Gambling Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042909

Chicago/Turabian StyleChóliz, Mariano. 2023. "Crisis, What Crisis? The Effect of Economic Crises on Spending on Online and Offline Gambling in Spain: Implications for Preventing Gambling Disorder" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042909

APA StyleChóliz, M. (2023). Crisis, What Crisis? The Effect of Economic Crises on Spending on Online and Offline Gambling in Spain: Implications for Preventing Gambling Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042909