People Living with HIV and AIDS: Experiences towards Antiretroviral Therapy, Paradigm Changes, Coping, Stigma, and Discrimination—A Grounded Theory Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Participation

2.2. Ethical Consideration

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Coding Paradigm

3.3. Central Phenomenon—Fast Coping with Diagnosis through a Paradigm Change

“The diagnosis really crushed me, it crushed me. But not for a long time. From being a woman who is ready to fight and wants to get through somehow…that’s when I was just crushed, that’s when I really ran out of steam at one point”.(I. 16 10–10)

“When I got the news, it pulled the rug out from under me. I walked through the streets like I was wrapped in absorbent cotton. A world collapsed for me, I was in panic”.(I. 22, 13–13)

“I intentionally said to myself, ‘You’ve got to get a handle on this now.’ I actively dealt with myself and the new situation. That hurt, but I knew I wasn’t lost, and I didn’t have to die, that’s what my doctor told me right away, that relieved me a lot. But you have to do it actively yourself. Just sitting around and waiting doesn’t work, I realized that”.(I. 16, 34–35)

“Today I am a consolidated and stable personality, good styling, I like myself, I am more confident today. Many react on the basis of old clichés and movies. Most of it took place in their own imagination. I’m glad I fought back in all the negative confrontations. Doing that made me more self-confident”.(I. 16, 53–53)

“It’s difficult. It’s been in my life for the last 32 years and it’s just a theme. It’s part of my life. For me, quality of life is being healthy and being comfortable in my body”.(I. 22, 21–21)

“Almost a bit like a relationship. Where you also sometimes argue but still totally appreciate each other and are glad to have the other person. I also just trust him. That’s what I’m so happy about, that I have such a doctor that I can trust. It’s such a personal relationship”.(I. 9, 6–6)

“I look for the doctors, nurses to have psychosocial competence. That’s a sign that you can talk about worries, fears, problems, that you also get to talk. That you are not immediately turned away in the office”.(I. 13, 54–54)

“There has been a paradigm shift between the knowledge of HIV from before and to what you get about HIV in terms of knowledge. HIV is no longer a problem today. The threat that you have a deadly disease with no chance is gone. It’s really just one pill a day, no more, no less. The importance of adherence has to do with viral load, that guarantees I can live to be old for a long time”.(I. 17, 15–15)

3.4. The Psychosocial Burden Caused by HIV

“What HIV does, it gnaws away at your self-esteem. You feel inferior. You feel like a second-class person, and you radiate that. It depends on how you communicate yourself about HIV and that’s how it comes across to the other person”.(I. 21, 27–27)

“The main aspect for me was really the topics of sexuality, shame and guilt. Coming to terms with the diagnosis, being able to accept it and this topic of shame and guilt and dealing with one’s own sexuality. That was very intense for me. I was in this shame and guilt theme. It’s not easy to talk about it with a subject. Talking with another woman about HIV”.(I. 16, 53–53)

“The flame that you have as a zest for life, that you want to go out, meet new people, that you might meet someone again on Tinder…but I don’t even want that anymore. It’s about socializing, which I avoid”.(I. 3, 8–8)

“I’m already also always struggling because I realize that I also keep falling into a hole and I’m not satisfied. That with my 56 years I’m still sitting in a rented apartment. I have no children and no partner. These are sometimes things that pull me down. But then I work on it. I can often no longer judge what comes from where. You don’t know if you have something physical or psychological if it comes from the medication or from HIV. I can’t tell anymore. Or is it the whole normal madness that occurs”.(I. 22, 22–22)

3.5. Antiretroviral Therapy as a Need

“For me it was important, this has to start right now. I needed this feeling; something has to be done against this virus. I was also very worried about my immune system. When I think about how many pills people take for any disease… I have to take one pill. If that is the solution, then the solution is very simple”.(I. 17, 12–12)

“It is important to me that I know every 3 months that the viral load fits anyway and that I am not infectious. That’s why I’m very consistent with taking ART. It is so routine and so automatic in my life to swallow these pills that I even have to be careful not to take them twice”.(I. 19, 23–23)

“I started ART right away. It worked great, right from the first dose. Adherence is not a problem for me, it works. I write it down every day, it’s ritualized”.(I. 24, 11–11)

“This is luxury these days. I take one tablet a day. That’s already an automatism. I never forget, it’s already in the flesh. I used to have to take a handful of tablets. Lots of side effects, lots of extra tablets to make the side effects bearable”.(I. 22, 25–27)

“I know I’m not infectious, but I don’t trust it 100 percent. Who knows, then I have more viruses in the body, and I infect someone, I could never agree with my conscience. We do only protected sexual intercourse”.(I. 3, 12–13)

“The prevention idea is already there. Take the one tablet, keep the same timing, then that’s your lifesaver”.(I. 17, 15–17)

“It’s important to me that nothing can happen, that I can’t infect anyone. That’s what’s in my head, just don’t infect anyone”.(I. 20, 13–13)

“Having a say is very important to me. I want to have a say, it’s my body and my HIV. It does everything I want it to do, if I want any minerals or anything checked out. I am very active myself, what I want to have examined. I want to know what’s going on inside me, after all”.(I. 24, 24–25)

“It’s totally important to me. I’m very interested in it. I always look at the values very carefully. I read up a lot and also research corresponding studies and read that. I find out about diseases immediately. I want to know everything exactly. I want to know what is in store for me. I also want to know about the effects of my medications”.(I. 14, 70–70)

3.6. Trust as a Requirement for HIV Disclosure

“It depends on do I say that to a neutral person, or do I say that to a man I want to go to have sex with…. My current boyfriend knows from the first night from my HIV-infection because I knew it was going to be more than a one-night stand. You can’t miss the moment to disclose the diagnose. You can’t have sex with someone before you talked about HIV. It has to be before. Otherwise, the trust is broken”.(I. 21, 27–27)

“HIV is a wall that has to be overcome. I’m not waiting for the right moment. If you don’t say that and have with sex, maybe that’s a cut you’ll never be in a relationship with then. Because of the basis of trust. That’s where you put obstacles in your own way”.(I. 13, 64–64)

“I think very specifically about who I tell about my HIV infection. I always ask myself whether this information is absolutely necessary now. And I ask myself whether I myself have a benefit, e.g., if I am ill and it is necessary that I tell my doctor, then I also do that. This is also about my own health and safety”.(I 6, 13–15)

“The most important thing for me is that I don’t want to be reduced to HIV. To be reduced to something that is not relevant in a friendship or in a family. HIV is still tainted with old stereotypes that are no longer relevant today”.(I. 19, 35–38)

“Of course, you are special. So, I already like to be the center of attention (laughs), but not as far as HIV is concerned, because it just has a negative touch at the end of the day and I don’t want to be reduced to that, I don’t want to be reduced to a disease or now ultimately an infection. But rather I want to be perceived as a human being at the end of the day”.(I. 9, 110–110)

“I also suffer from having this fat distribution disorder. I got a big uneven breast. I suffered a lot from that. That’s when I had a breast reduction. It has become better. Of course, the beauty also suffers, and the disease becomes visible”.(I. 18, 55–55)

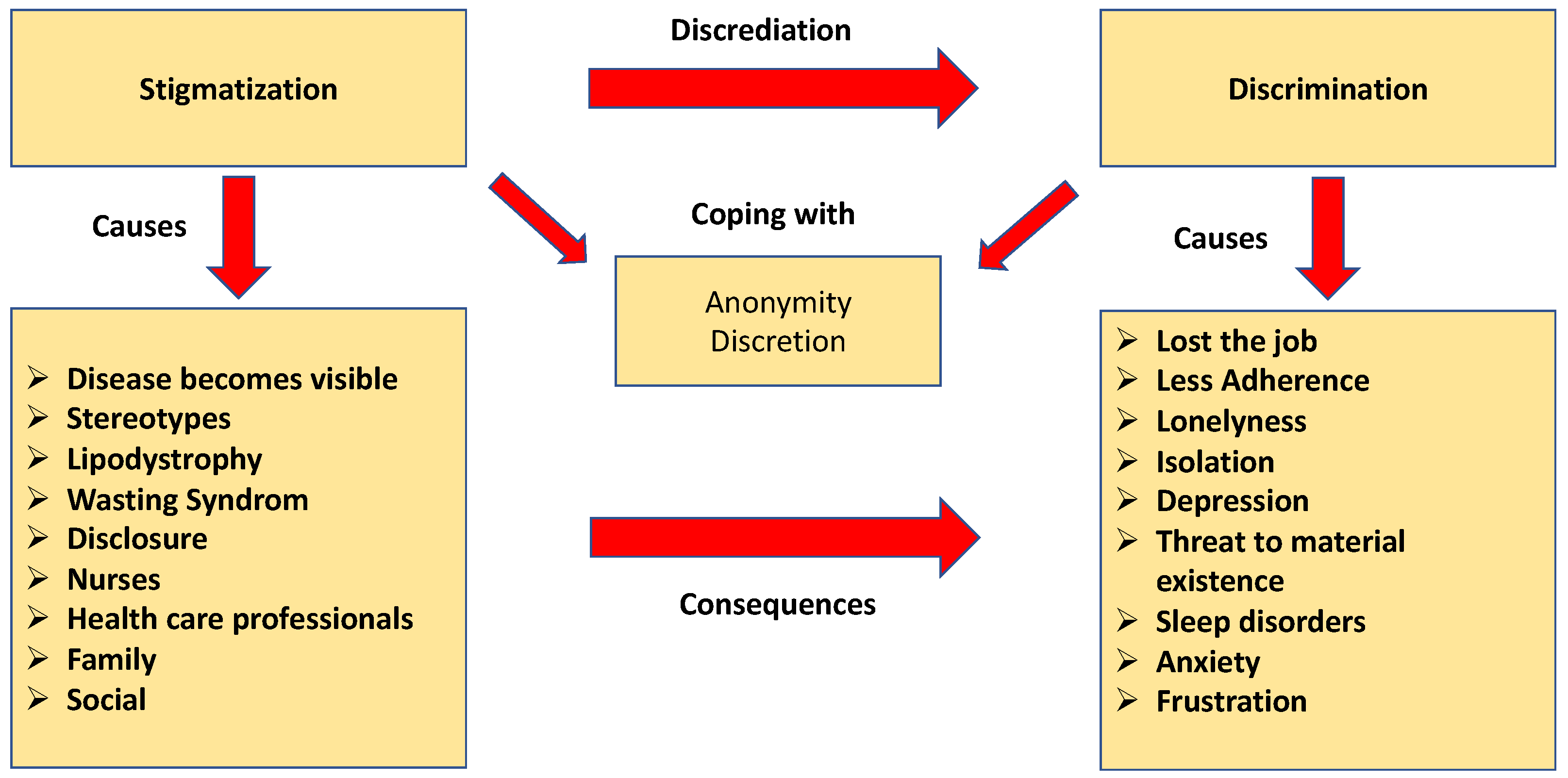

3.7. Stigmatization and Discrimination

“I have had no appetite for a long time and have lost a lot of weight. I was very tired, and I felt very bad. I was listless and my circulation did not work. It was hard for me to get through the workday because of these fatigue attacks. My boss often asked me what was wrong with me, and I always had to make excuses and lie. But it was obvious to everyone that I was seriously ill. At some point I couldn’t take it anymore and told them I was diagnosed with HIV. After that, I was no longer acceptable at work because of the diagnosis”.(I. 5, 34–35)

“If more social acceptance was there, where you could talk about HIV exactly o, like you could talk about a herniated disc, for example, you could talk about it more easily and much more often. Not always just this stigma, you can’t talk about it”.(I. 16, 68–69)

“I looked for a gynecologist for a long time, no one would take me. Now I finally found one, but I always get the appointment last thing in the evening…”.(I. 23, 15–16)

“The Dentist turned me down. I was there I was in shock”.(I. 22, 14–14)

“When I told the dermatologist that I am HIV positive to protect her…..she insulted me and kicked me out of the office…”.(I. 16, 13–13)

“…then the virus got a point of attack… I lost a lot of weight, I got emaciated, people were pestering me at work, what’s wrong with me? A bad pressure built up in my head that I could no longer hold. And then when I came out, the bullying started, from my bosses. They said, you can’t continue this work anymore… I got worse and worse until I was fired”.(I. 11, 16–16)

“Now I myself belong to this rabble… Yes, I don’t want to call myself an HIV hater, for me it was just hard to become one of them. Of course, that doesn’t sound nice, but that’s how I saw it and meanwhile I understand the people. But still there is a side with me where I think oh God, you are one of these freaks, yes exactly”.(I. 3, 18–18)

“Stigmatization is still as bad in certain strata of society as it was 20 years ago. It’s still a dirty disease. It still has that connotation. But people don’t know that HIV-positive people are no longer contagious. That has not been conveyed in the media”.(I. 21, 22–22)

“It’s fundamentally embarrassing to me, it’s so very afflicted. It’s so badly afflicted. With homosexuality, drugs, that’s enough, that’s already 90 percent of people what goes through their heads when they think of HIV, forget it, never. I would advise everyone not to say this to anyone, especially at work. Because there are people who are like I used to be, who don’t want to have anything to do with people like that. It’s too negative, I had to learn to see it from a different perspective, that I’m not a monster”.(I. 3, 46–46)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alejos, B.; Suarez-Garcia, I.; Rava, M.; Bautista-Hernandez, A.; Gutierrez, F.; Dalmau, D.; Sagastagoitia, I.; Rivero, A.; Moreno, S.; Jarrin, I. Effectiveness and safety of first-line antiretroviral regimens in clinical practice: A multicenter cohort study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3004–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armoon, B.; Higgs, P.; Fleury, M.-J.; Bayat, A.-H.; Moghaddam, L.F.; Bayani, A.; Fakhri, Y. Socio-demographic, clinical and service use determinants associated with HIV related stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, Y.A.; Yitayal, M.; Atnafu, A.; Taye, F.A. Patient experiences and preferences for antiretroviral therapy service provision: Implications for differentiated service delivery in Northwest Ethiopia. AIDS Res. Ther. 2022, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickel, M.; Hoffmann, C.; Wolf, E.; Baumgarten, A.; Wyen, C.; Spinnter, C.D.; Jäger, H.; Postel, N.; Esser, S.; Museller, M.; et al. High effectiveness of recommended first-line antiretroviral therapies in Germany: A nationwide, prospective cohort study. Infection 2020, 48, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogart, L.M.; Cowgill, B.O.; Kennedy, D.; Ryan, G.; Murphy, D.A.; Elijah, J.; Schuster, M.A. HIV-Related Stigma among People with HIV and their Families: A Qualitative Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2008, 12, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.L.; Vanable, P.A.; Bostwick, R.A.; Carey, M.P. A Pilot Intervention Trial to Promote Sexual Health and Stress Management among HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhwani, H.; Gakumo, C.A.; Yigit, I.; Rice, W.S.; Fletcher, F.E.; Whitfield, S.; Ross, S.; Konkle-Parker, D.J.; Cohen, M.H.; Wingood, G.M.; et al. Patient Health Literacy and Communication with Providers among Women Living with HIV: A Mixed Methods Study. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention CDC. Protecting Others. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/livingwithhiv/protecting-others.html (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Carneiro, P.B.; Westmoreland, D.A.; Patel, V.V.; Grov, C. Awareness and Acceptability of Undetectable = Untransmittable among a U.S. National Sample of HIV-Negative Sexual and Gender Minorities. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, D.; De Terte, I.; Gardner, D. Posttraumatic Growth and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in People with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 3688–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1996, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, M.; Lampe, F.C.; Sherr, L.; Phillips, A.N.; Johnson, M.A.; Gilson, R.; Perry, N.; Wilkins, E.; Lascar, M.; Collins, S.; et al. Non-Disclosure of HIV Status and Association with Psychological Factors, ART Non-Adherence, and Viral Load Non-Suppression among People Living with HIV in the UK. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawoson-Rose, C.; Cucac, Y.P.; Webel, A.; Baez, A.R.; Holzember, W.; Rivero-Mendez, M.; Eller, L.S.; Reid, P.; Johonson, M.O.; Kemppainen, J.; et al. Building Trust and Relationship between Patients and Providers: An Essential Complement to Health Literacy in HIV Care. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2016, 27, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe 2017–2016 Data. Available online: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/20171127-Annual_HIV_Report_Cover%2BInner.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Evangeli, M.; Wroe, A.L. HIV Disclosure Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Theoretical Synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauci, A.S.; Lane, C. Four Decades of HIV/AIDS—Much Accomplished, Much to Do. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlatte, O.; Handlovsky, I.; Ridge, D.; Chanady, T.; Knight, R.; Oliffe, J.L. Understanding stigma and suicidality among gay men living with HIV: A photovoice project. SSM—Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.M.; Koester, K.; Guinness, R.R.; Steward, W.T. Patient’s Perceptions and Experiences of Shared Decision-Making in Primary HIV Care Clinics. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2017, 28, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbidon, K.; Chenneville, T.; Peless, T.; Sheared-Evans, S. Self-Disclosure of HIV Status among Youth Living with HIV: A Global Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasvand, H.; Waye, K.M.; Noroozi, M.; Harouni, G.G.; Armoon, B.; Bayani, A. Clinical determinants associated with quality of life for people who live with HIV/AIDS: A Meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Über Techniken der Bewältigung Beschädigter Identität, 3rd ed.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, G.L.; Wilson, A.; Bansal, G.P.; Barnhart, C.; Barr, E.; Berzon, R.; Boyce, C.A.; Elwood, W.; Gamble-George, J.; Glenshaw, M.; et al. HIV-related Stigma Research as a Priority at the National Institute of Health. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26 (Suppl. S1), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo, E.; Giordano, T.; Westbrook, R.A.; Black, W.C.; Njue-Marendes, S.; Dang, B.N. The Effect of Initial Patient Experiences and Life Stressors on Predicting Lost to Follow-Up in Patients New to an HIV Clinic. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 1880–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, Z.M.; Naugle, D.A.; Tibbels, N.; Dosso, A.; Van Lith, L.M.; Mallalieu, E.C.; Kamara, D.; Dailly-Ajavon, P.; Cisse, A.; Seifert Ahanda, K.; et al. “You Take Medications, You Live Normally”: The Role of Antiretroviral Therapy in Mitigating Men’s Perceived Threats of HIV in Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 2600–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewko, S.J.; Cummings, G.G.; Pietrosanu, M.; Edwards, N. The Impact of Quality Assurance Initiatives and Workplace Policies and Procedures on HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma Experienced by Patients and Nurses in Regions with High Prevalence of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3836–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, C.; Rockstroh, J. HIV Buch. Available online: https://www.hivbuch.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/HIV2020-21-1.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Ingersoll, K.S.; Heckman, C.J. Patient-Clinician Relationship and Treatment System Effects on HIV Medication Adherence. AIDS Behav. 2005, 9, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.; Wachira, J.; Kafu, C.; Braitstein, P.; Wilson, I.B.; Harrison, A.; Owino, R.; Akinyi, J.; Koech, B.; Genberg, B. The Role of Gender in Patient-Provider Relationships: A Qualitative Analysis of HIV Care Providers in Western Kenya with Implications for Retention in Care. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laws, B.M.; Wilson, I.B.; Bowser, D.M.; Kerr, S.E. Taking Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection. Learning from Patients’ Stories. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Stigma and its public health implication. Lancet 2006, 367, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyimo, R.A.; Stutterheim, S.E.; Hospers, H.J.; de Glee, T.; van der Ven, A.; de Bruin, M. Stigma, Disclosure, Coping, and Medication Adherence among People Living with HIV/AIDS in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014, 28, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marni, R.N.; Nurtanit, S.; Handayani, S.; Ratnasari, N.Y.; Susanto, T. The Lived Experience of Women with HIV/AIDS: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 11, 1475. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, R.S.; Boonsuk, P.; Dandu, M.; Sohn, A.H. Experiences with stigma and discriminiation among adolescents and young adults living with HIV in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Care 2020, 32, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulsby, C.H.; Ratnayake, A.; Hesson, D.; Mugavero, M.J.; Latkin, C.A. A Scoping Review of Employment and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 2942–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNairy, M.; Deryabina, A.; Hoos, D.; El-Sadr, W. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission: Potential role for people who inject drugs in Central Asia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 132 (Suppl. S1), S65–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modula, M.J.; Raumukumba, M.M. Nurses’ implementation of mental health screeing among HIV infected guidelines. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 8, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mugo, C.; Seeh, D.; Guthrie, B.; Moreno, M.; Kumar, M.; John-Stewart, G.; Inwani, I.; Ronen, K. Association of experienced and internalized stigma with self-disclosure of HIV status by youth living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 2084–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigusso, F.T.; Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A.H. Health-related quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS: The role of social inequalities and disease-related factors. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, R.K.; Sousa, L.R.M.; Santos Melo, E.; Martinez Fernandes, N.; Sorensen, W.; Gir, E. Predictors of HIV Status Disclosure to Sexual Partners among People Living with HIV in Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3538–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remien, R.H.; Hirky, A.E.; Johnson, M.O.; Weinhardt, L.S.; Whittier, D.; Le, G.M. Adherence to Medication Treatment: A Qualitative Study of Facilitators and Barriers among a Diverse Sample of HIV+ Men and Women in Four U.S. Cities. AIDS Behav. 2003, 7, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rintamaki, L.; Kosenko, K.; Hogan, T.; Scott, A.M.; Dobmeier, C.; Tingue, E.; Peek, D. The Role of Stigma Management in HIV Treatment Adherence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seffren, V.; Familiar, I.; Murray, S.M.; Augustinavicius, J.; Boivin, M.J.; Nakasujja, N.; Opoka, R.; Bass, J. Association between coping strategies, social support, and depression and anxiety symptoms among rural Ugandan women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbayi, L.C.; Kalichman, S.; Strebel, A.; Cloete, A.; Henda, N.; Mqeketo, A. Inernalized stigma, discrimination, depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1823–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Cook, R.; Rohleder, P. Taking into Account the Quality of the Relationship in HIV Disclosure. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovski, K.; King, E.J.; Amico, K.R.; Eisenberg, M.C.; Geronimus, A.T.; Baros, S.; Schmidt, A.J. Stigmatizing Policies Interact with Mental Health and Sexual Behaviours to Structurally Induce HIV Diagnose among European Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 3400–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory: Grundlagen Qualitativer Sozialforschung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeny, S.M.; Vanable, P.A. The Association of HIV-Related Stigma to HIV Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, M.D.; Brickley, D.B.; Vinh, D.T.N.; Colby, D.J.; Sohn, A.H.; Trung, Q.; Giang, L.T.; Mandel, J.S. A Qualitative Study of Stigma and Discrimination against People Living with HIV in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2008, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Madriz, G.; Lerner, D.; Ruthazer, R.; Rogers, W.H.; Wilson, I.B. Work-related Barriers and Facilitators to Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Persons Living with HIV-Infection. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, B.; Budhwani, H.; Fazeli, P.L.; Browning, W.R.; Raper, J.L.; Mugavero, M.J.; Turan, J.M. How Does Stigma Affect People Living with HIV? The Mediating Roles of Internalized and Anticipated HIV Stigma in the Effects of Perceived Community Stigma on Health and Psychosocial Outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Vieira de Lima, I.C.; Galvao, M.T.G.; Alexandre, H.; Lima, F.E.T.; de Araujo, T.L. Information and communication Technologies for adherence to antiretroviral treatment in adults with HIV/AIDS. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 92, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-X.; Golin, C.; Bu, J.; Emrick, C.B.; Nan, Z.; Li, M.-Q. Coping Strategies for HIV-Related Stigma in Liuzhou, China. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Domain Patient Interview | Questions |

|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS | How are you doing right now? Tell me about the diagnosis of HIV? How long have you been living with HIV? |

| Antiretroviral therapy Relationship with the treatment team | Tell me about the antiretroviral therapy. What are the challenges? How can the regular intake be adhered to? Describe the relationship with the treatment team. |

| Discrimination and stigma | Tell me about experiences and exposure to discrimination and stigma. |

| Gender-specific characteristics | How does a woman/man live with HIV? Are there gender-specific differences? |

| Physical and psychosocial burden | What burdens arise in daily life? How is the coping? |

| PLWH | Sex | Sexual Orientation | Age | HIV in Years | ART | Occupation | Marital Status | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | MSM | 30 | 6 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 2 | m | MSM | 55 | 20 | unemployed | single | A | |

| 3 | m | MSW | 45 | 25 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 4 | m | MSM | 33 | 4 | employed | single | A | |

| 5 | f | heterosex | 55 | 25 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 6 | m | MSM | 22 | 2 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 7 | m | MSM | 50 | 30 | retired | partnership | G | |

| 8 | m | MSM | 25 | 1.5 | employed | single | G | |

| 9 | m | MSM | 42 | 15 | employed | single | A | |

| 10 | f | heterosex | 60 | 30 | unemployed | single | A | |

| 11 | m | MSM | 64 | 38 | retired | single | A | |

| 12 | f | heterosex | 56 | 36 | retired | single | A | |

| 13 | f | heterosex | 49 | 21 | employed | single | A | |

| 14 | f | heterosex | 58 | 38 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 15 | m | MSM | 34 | 2 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 16 | f | heterosex | 52 | 17 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 17 | m | MSM | 25 | 2 | employed | single | A | |

| 18 | f | heterosex | 25 | 25 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 19 | m | MSM | 45 | 4 | employed | partnership | A | |

| 20 | m | MSM | 54 | 1 | employed | single | G | |

| 21 | f | heterosex | 43 | 21 | employed | single | G | |

| 22 | f | heterosex | 56 | 31 | employed | single | G | |

| 23 | m | MSM | 60 | 30 | employed | partnership | G | |

| 24 | m | MSM | 32 | 2 | employed | single | A | |

| 25 | f | heterosex | 50 | 32 | employed | single | G |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beichler, H.; Kutalek, R.; Dorner, T.E. People Living with HIV and AIDS: Experiences towards Antiretroviral Therapy, Paradigm Changes, Coping, Stigma, and Discrimination—A Grounded Theory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043000

Beichler H, Kutalek R, Dorner TE. People Living with HIV and AIDS: Experiences towards Antiretroviral Therapy, Paradigm Changes, Coping, Stigma, and Discrimination—A Grounded Theory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043000

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeichler, Helmut, Ruth Kutalek, and Thomas E. Dorner. 2023. "People Living with HIV and AIDS: Experiences towards Antiretroviral Therapy, Paradigm Changes, Coping, Stigma, and Discrimination—A Grounded Theory Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043000

APA StyleBeichler, H., Kutalek, R., & Dorner, T. E. (2023). People Living with HIV and AIDS: Experiences towards Antiretroviral Therapy, Paradigm Changes, Coping, Stigma, and Discrimination—A Grounded Theory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043000