1. Introduction

Currently, society has shown a massive interest in Environmental Consciousness (CE), where industries are concerned with mitigating environmental damage resulting from their economic activities [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Since December 2019, the international health crisis related to COVID-19 allowed the evaluation of environmental impacts in different contexts. In this vein, COVID-19 has deeply affected economic structures, as well as social and commercial relations. Particularly, the pandemic has been a phenomenon that has generated positive and negative effects on the global environment [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Restrictions to the free movement between and through the region’s urban areas decreased economic activity as well as the use of cars, trucks, and other motorized vehicles. As a result, many cities in Latin America experienced a short-run air pollution reduction. For example, Bogotá showed the most significant decrease (−83%), and Guayaquil, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo were the cities with the lowest reduction of 30% [

10], places that historically had problems with environmental pollution. In this sense, the pandemic and lockdown measures have temporarily reduced urban pollution in many Latin American cities. Additionally, COVID-19 has positively decreased water and noise pollution due to confinement in homes and travel restrictions [

11], improving the efficiency of the consumption of a natural resource in permanent monitoring for its potential shortages in the coming years. An additional positive consequence of this pandemic is the generation of a collective awareness regarding protecting the environment and the need to conserve natural resources [

12]. Indeed, negative environmental contexts positively affect the responsible environmental behavior of the population, which has been observed in the context of COVID-19 [

13].

On the other side, we face a consumer society of manufactured products and services that negatively affect the environment [

14,

15]. This situation was aggravated with the arrival of COVID-19, where individuals around the world have adopted an excessive use of disinfectants and disposable materials such as face shields, masks, bags, and other products related to the prevention of the spread of the virus that caused a high amount of plastic and sanitary waste [

16].

Environmentally responsible behavior can facilitate improving the environment and advancing a sustainable society [

17,

18,

19]. In this context, emergent research findings have linked the effects of COVID-19 on consumers’ perceptions, environmental awareness, or/and purchase intention [

20,

21,

22,

23]. However, the literature on the relationships proposed in the explanatory model is still scarce at a theoretical and practical level, with no empirical evidence in Latin America.

Based on the above, the experience of this world crisis could lead to changes in behavior at the collective and individual levels. Therefore, there is a research gap to empirically evaluate if this is observed in different contexts, especially in Latin American consumers, since there is very little evidence exploring this phenomenon in this geographical area. The importance of a better understanding of the potential effects of COVID-19 on environmentally responsible behavior is the insights that new evidence can provide for designing behavior-based government and business policy instruments that focus on changing consumption and production patterns [

24].

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is one of the most relevant social psychology theories; it explains individual behavioral intentions [

25] and is the theoretical approach applied in this research. This theory was built based on the seminal work of Fishbein and Ajzen [

26] and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which explains human actions as a consequence of behavioral intentions that are influenced by attitudes and perceived social pressure. Later, in 1985, Ajzen argued that in addition to the Theory of Reasoned Action, when it comes to human behavior, it is necessary to consider the perception of perceived control of internal or external factors that influence determined behavior (locus of control) [

27]. According to Ajzen [

28], three main factors in TPB influence individual behavior. First, attitudes refer to the degree to which a person values, positively or negatively, a behavior [

27,

29]. Second, Subjective Norms, are the social pressure or normative expectations of social groups to which individuals belong. Third, Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) is a predictor that reflects the ease or difficulty of the individual’s perception of performing a particular behavior [

28,

30]. In this sense, this variable is analyzed from self-efficacy, which corresponds to the individual’s degree of effort to conduct a potential behavior [

30,

31]. Therefore, the three determinants of this theoretical approach can be observed at individual and social levels. While in 1992, it was argued that TPB is a better theoretical framework than TRA to predict human behavior [

27], recent research suggests and recommends the application of TPB as a broader and more appropriate predictor to understand consumer behavior [

32,

33,

34].

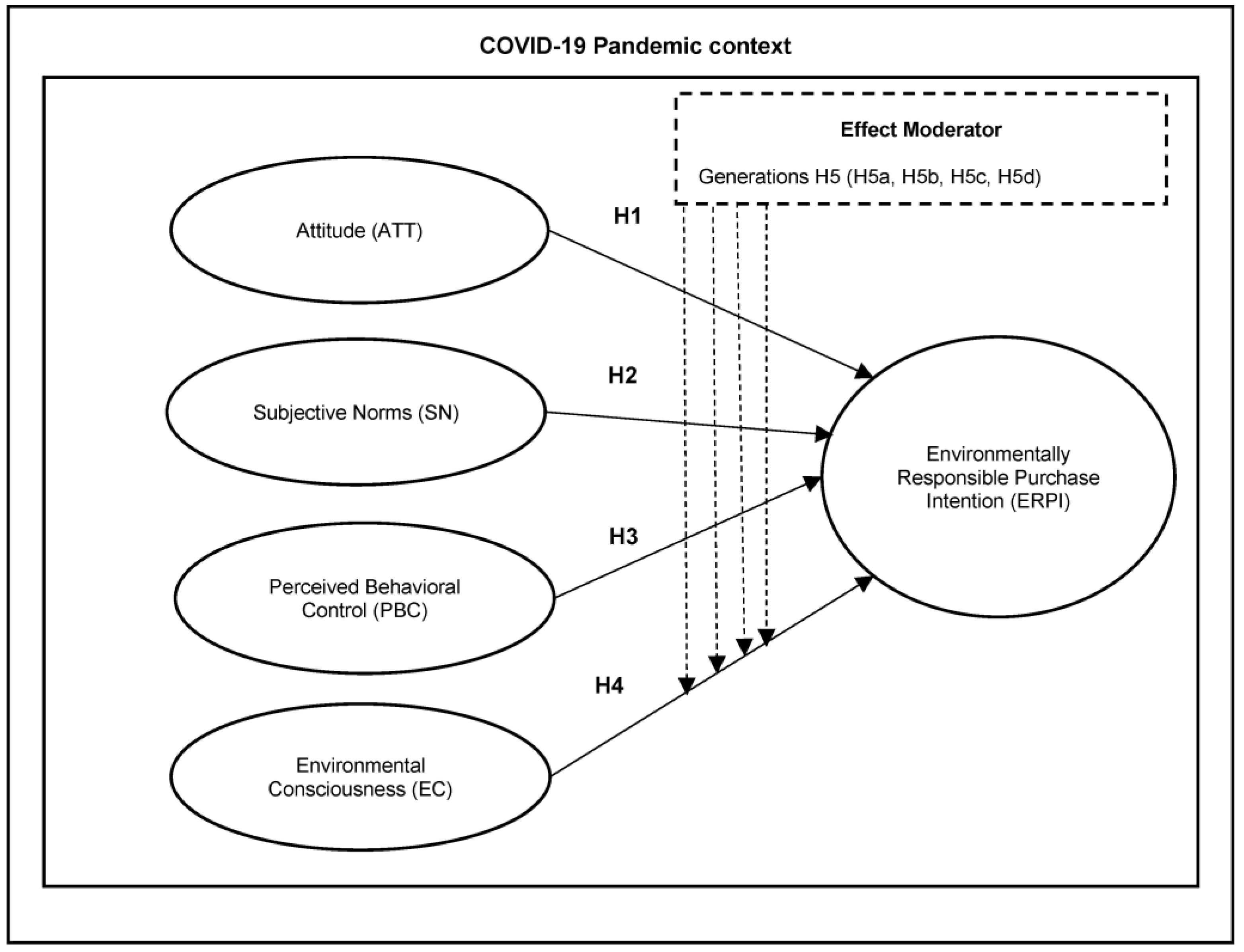

The main purpose of this study is to contribute to the theoretical and empirical gap about the effects of COVID-19 on environmentally responsible behavior in Latin American countries from a TPB perspective. Therefore, the main contributions of this article are (1) to understand and corroborate the effect of COVID-19 on Latin American consumers’ declaration of Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI); (2) to test the validity, reliability, and statistical significance of each hypothesis of the explanatory model by using structural equation modeling (SEM); (3) to examine the estimation performance of the extended TPB model for Latin American consumers; (4) to test moderating effect and test invariance for the hypothesis of the model by using multi-group of generations.

Thus, to fill this gap, this study responds to the lack of research to examine the relationship between the following dimensions a) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), composed of Attitudes (ATT), Subjective Norms (SN), and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC); and b) Environmental Consciousness (CE), on the dependent variable of Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI) from the perspective of the Latin American consumer in a pandemic context. Building upon Severo et al. [

4] and Xu et al. [

23], this study presents a quantitative statistical analysis employing Structure Equation Modelling (SEM).

The rest of the article is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides the conceptual background and hypotheses of this research.

Section 3 details the research methodology.

Section 4 presents the results.

Section 5 offers a discussion of our evidence based on theoretical and managerial implications identified in the field. Finally, the article presents the main conclusions and identifies future research avenues.

3. Methodology

3.1. Context and Method

This article aims to examine and understand the effects of COVID-19 on environmentally responsible purchase intention. More specifically, this research focused on how COVID-19 has influenced Attitudes, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Environmental Consciousness. This work was carried out from consumers’ perspectives in Latin American countries through a quantitative method. The sample data included consumers from Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

For this study, the global explanatory model is composed of formative constructs and reflective indicators. That is, the independent variables are formative of the dependent variable, and the indicators representing each construct or variable are reflective. After defining the formative or reflective nature of the indicators of the constructs or variables established in the model, we evaluate the measurement model.

In this study, a cross-sectional research method was applied through a self-administered questionnaire [

88]. The selected instrument was proposed through pre-established and validated scales [

15]. The survey was applied in Spanish-speaking countries. Therefore, it was necessary to use the back-translation method proposed by Brislin [

89].

3.2. Sample and Procedure

COVID-19 has caused different confinement and social distancing restrictions in Latin American countries [

90]. For this reason, this research utilized an online survey method through the Google form platform. The survey was applied to local people in Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico for three months (July to September 2021). In addition, the authors decided to share the questionnaire on the internet through social networks, such as Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, e-mail, and WhatsApp.

Since the literature on the relationships proposed in the explanatory model is still scarce at a theoretical and practical level, with no empirical evidence in Latin America, this study is exploratory [

91]. A non-probabilistic and convenience data sampling method was applied to collect data [

92]. Furthermore, the snowball sampling method was used through social networks. This technique makes it possible to expand the geographical location and reduce the respondents’ access barriers [

93,

94]. This research is ad hoc to apply this method to minimize respondents’ risk of COVID-19. Moreover, social networks and the internet contribute to the non-probabilistic aspect of random and diverse respondents [

95].

Respondents were informed that the data collected would be used exclusively for academic purposes, and the data were analyzed anonymously. Consequently, sociodemographic information was analyzed to understand the study sample. This procedure resulted in a sample size of 1624 consumers who responded to the survey in four countries. The sample per country was 24.6% from Chile (n = 400), 25.9% from Colombia (n = 421), 24.7% from Mexico (n = 401), and 24.8% from Peru (n = 402). The sample is equitable between each country; therefore, the research sample size meets the required requirements [

96].

The sample data showed most of the participants were women. There were 943 female participants (58.1%), followed by 670 male participants (41.3%), and 7 participants (0.6%) of the respondents decided not to reveal their gender. In terms of age, the sample was categorized by groups of age, generation X (11.7%, n = 190), generation Y (millennials) (42.9%, n = 697), and generation Z (45.4%, n = 737).

Since the present work is an exploratory study [

91], consistent with the type of non-probability sampling [

97], it is not possible to calculate sampling errors. However, being the smallest sample size of 197 and when analyzing the composite reliabilities of the whole sample, the values in all factors were high (>0.90). This indicates that the items adequately measure the intended factor, which is why the literature considers it appropriate to work with small samples [

92].

After the study was carried out, to verify that the differences in the subsample sizes concerning the generation did not constitute a problem, the power analysis was performed using the independent samples

t-test (given that they are different generations), using SPSS-27. This was determined using the smallest sample (197) and the most significant sample (737) because they are the most distant and to ensure greater reliability in these results. The power analysis shows a value of 0.980, which is above 0.80 of the minimums required, which allows us to affirm that there is no problem with distant sample size differences [

98] (See

Table 1).

The final sample collection was classified into five groups according to the total monthly income. First, the sample reveals a higher percentage of participating people who declare earning at least two minimum salaries in their country (36.8%, n = 598). Then, followed by three and four average minimum salaries (25.4%, n = 413), a third group that has declared between five and ten average minimum salaries (23.6%, n = 376), and then a group has from eleven to twenty minimum average salaries (9.5%, n = 155), and finally a small group over twenty minimum salaries (5.0%, n = 82).

3.3. Measures

To construct this model research, the items were adopted from previous studies. Eight academics from different areas, such as marketing, management, and sustainability, tested and evaluated the questionnaire to check the scales and items.

The final questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first section presented 18 questions related to the COVID-19 effects on environmentally responsible purchase intention. Specifically, this section was separated into six dimensions with three-item each.

The four independent variables used in our model were (i) Attitude (ATT) [

9,

17], (ii) Subjective Norm (SN) [

9,

67], (iii) Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) [

9,

74], and (iv) Environmental Consciousness (EC) [

9,

75,

76], and the dependent variable was (v) Environmental Responsibly Purchase Intention (ERPI) [

9]. Finally, the moderating variable was age, using generations X, Y, and Z.

The second section was related to six questions about demographic data, such as country, age, gender, income, educational level, and civil status.

Every item was written as a statement to be evaluated (See

Table 2), applying a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). In this sense, all the participants interviewed were explained every number and item to understand and respond adequately [

99].

3.4. Statistical Analysis

To establish the identification of the proposed explanatory model, we verified that the two most basic heuristic rules are fulfilled. In this sense, all the constructs have at least three indicators, and it is a recursive model.

The first statistical process evaluated the reliability and validity model. Specifically, this study measured the reliability of latent variables and the internal consistency of the items using the Cronbach Alpha method. Then, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied to verify the fit and measurement model. The research employed two statistical software. First, the IBM SPSS Statistics software was used to check the convergent and discriminant validity. Secondly, the AMOS Software was selected to test and propose the model and hypothesis through a multi-group Structure Equation Modelling (SEM).

SEM is considered a suitable method for this type of research. First, this method is highly recommended to evaluate cause–effect relations in descriptive models [

92]. Secondly, SEM is a perfect method to test the hypothesis of dependence relationships, correlations, and effects of moderating variables [

104]). Finally, recent studies applied SEM to analyze and demonstrate robustness in measures and structural assessment [

15,

105,

106].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This research was conducted to empirically evaluate different factors that can affect the Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention of consumers in Colombia, Mexico, Chile, and Peru in the context of COVID-19. The global explanatory model is composed of formative constructs and reflective indicators. This explanatory model is composed of five independent variables that collectively explain a phenomenon related to the dependent variable, Environmental Responsibly Purchase intention [

117,

118,

119,

120]. The results show evidence that supports the hypothesis proposed in prior studies concerning COVID-19’s influence as a phenomenon that has affected the population regarding environmental issues in society [

1,

4]. In terms of research findings (see

Table 7), our main theoretical contribution is that our evidence supports the idea that Attitude (ATT), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and Environmental Consciousness (EC) would influence the Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI), which are discussed as follows.

First, Attitudes (ATT) determined Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our evidence is aligned with previous research indicating that behavioral attitudes are an essential factor in purchasing process when products are created based on eco-friendly methods that facilitate further recycling behavior [

22]. Based on the above, this research is aligned with previous research by arguing that ERPI is influenced by Attitudes [

55,

56,

57]. This is consistent with Shen et al. [

25], who have argued that during COVID-19, the attitude toward the intention to purchase products has increased. One possible explanation for this outcome is that quarantines and voluntary self-isolation during the have had an emotional impact on consumers, which is in line with the perspective of Nguyen et al. [

121] and the relation of ATT and consumer behavior, specifically in the youngest generations. For example, it has been highlighted in Colombia Attitude is one of the most critical aspects of decision-making from social and economic perspectives [

122].

Second, our research also suggests that COVID-19 determined Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC). This conclusion is consistent with prior studies such as Xu et al. [

23], Lucarelli et al. [

71], and Vu et al. [

56], who found that PBC affects purchasing intention related to pro-environmental behavior. Mexico and Chile support the hypothesis, both countries being Latin American members of the OECD. It last could partially explain political and economic conditions that are necessary to be part of this international organization and that directly influence how those countries promote economic development, but that consider elements of protection of the environment, which could be reflected in the behavior of consumers. In terms of age, this hypothesis was supported in generations Y and Z, reflecting that COVID-19 would contribute to the relationship between Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) and Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI) in the younger generations.

Third, our evidence indicates that COVID-19 determined Environmental Consciousness (EC) in Latin American countries. In line with previous studies, our results show that Environmental Consciousness (EC) is an essential motivator for developing behavioral intention [

1,

41]. It is important to note that the results show that the pandemic scenario positively influenced the relationship between Environmental Consciousness (EC) and Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI) in all countries and all generations, demonstrating that this worldwide crisis has generated an effect on consumers, which could demonstrate the starting point towards a transition that establishes environmentally friendly behaviors [

5,

75]

On the opposite side, the current investigation rejects H2. In this sense, our results have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has not positively contributed to the relationship between Subjective Norms (SN) and Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI). This can be explained because quarantines and social distancing have significantly reduced interaction between family, friends, and co-workers. Consequently, there were not enough social encounters for a social influence on behaviors toward an environmentally responsible purchase intention.

5.1. Practical and Managerial Implications

Different from the existing research in a context without a COVID-19 pandemic on the factors of Environmental Responsibly Purchase intention (ERPI) [

15,

23,

51,

52], our research proposes a research framework in Latin America focused on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically on consumer behavior regarding Attitude (ATT), Subjective Norm (SN), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and Environmental Consciousness (EC).

Regarding the practical implications of this research, there is a significant finding about the moderating effect on Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention across generational groups. Our results indicate that age plays a moderator role in Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention (ERPI) in generation X. Moreover, Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) influences the younger groups (Y and Z). In this sense, young adults (Generation Z) and adults (Generation Y) are the ones who are susceptible to the potential impacts of COVID-19 in their intention to make an environmentally responsible purchase.

This could be explained due to younger groups manifesting greater environmental awareness [

4] and online digitization [

123], which has influenced the accessibility of information and environmental concerns during COVID-19. Building upon Nguyen [

121], it is possible to argue that young consumers represent a powerful force in developing environmental awareness among the population, specifically within emerging markets such as the ones observed in Latin American countries. In this scenario, as a guideline for companies operating in this context, they should diversify their strategies to promote environmentally responsible purchase behavior by considering how different generations address the need for sustainability in purchasing processes, understanding that there is a different understanding and awareness of the environmental urgency on the planet.

This research offers suggestions and implications for managerial decision making. Our findings provide strong evidence of environmental developments in Latin American countries during the pandemic of COVID-19, allowing us to propose realistic prepositions for governments and companies. For example, Environmental Consciousness has increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, manifested in consumers making efforts to prefer green products that are less harmful to the environment [

4]. Therefore, companies should adopt sustainable and eco-friendly business practices to align with customers’ individual behavior. For example, businesses should promote the recycling and disposal of supplies in their packaging and stores to educate the population and facilitate the process [

7]. In turn, advertising campaigns raise awareness of a brand that is friendly and close to its clients. In addition, business owners and executives must test new business models in response to the rise of online purchases and buy withdrawals at the collecting point. Since the quarantine and isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, customers have temporarily or permanently altered their shopping habits.

Finally, local governments should evaluate this social context and support activities that positively influence our world from a national approach. The authorities should develop policies that help the transformation towards a more sustainable world—for example, proposing public programs to reduce pollution, recycling incentives, and promoting efficient water consumption.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

This research has addressed the COVID-19 effects on environmentally responsible behavior, delivering theoretical and practical implications. However, some limitations should be considered for future research.

The first limitation refers to the sample; the sample is a non-probabilistic and simple cross-section. The participants responded voluntarily, giving their perception of the environmentally responsible purchase Intention. Additionally, this research only included participants from Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

For this reason, it is recommended in future research to expand the sample to other Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Venezuela in South America; or Central American countries, such as Panama, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, or Costa Rica [

124,

125]. As a result, a more extensive and diverse sample is expected to provide an opportunity to develop a cross-cultural study [

126,

127] or theoretical model based on human values in the context of geographical distances [

128]. However, this limitation makes it difficult to generalize the results obtained in this scenario. Consequently, it is thus advised an expansion of this study employing a stratified random sample to compare generation consumers or cross-country consumer research [

129]. In this context, the sample distribution should be extended for different age groups to analyze the possible effect size.

Secondly, this study only focused on the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic (between the third and fourth waves) in consumer behavior in the context of environmentally responsible purchase intention. For this reason, our results are not generalizable to the post-pandemic stage. Future studies may consider the environmental situation in a post-pandemic context to identify if the eco-friendly and pro-environmental behavior is maintained over time or was just a stationary effect.

Thirdly, another limitation is the method of collecting data. Our research carried out an online survey like most studies in times of COVID-19 due to quarantines, limited capacity, and social distancing. Therefore, consumer behavior has not been evaluated in real-time, so future post-pandemic research could use field surveys to immediately consult consumers about their purchase intention and behavior.

Finally, a fourth relevant limitation is people’s honesty when responding. As in other studies on pro-environmental behavior, it is possible that the respondents feel a social and ethical pressure to respond to show environmental interest. For this reason, the results must be evaluated and generalized with caution. Consequently, it is crucial to understand the gap between purchase intention and purchase experience. This occurs because a group of consumers provides a positive attitude toward society about a friendly purchase with the environment. However, these do not usually finalize the purchase. For this reason, future research should focus on filter questions to identify an effective and real purchase intention.