Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection Procedure and Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Meta-Analysis of Suicidal Ideation for Non-Clinical and Clinical Samples

3.2.1. Overview

3.2.2. Non-Clinical Samples

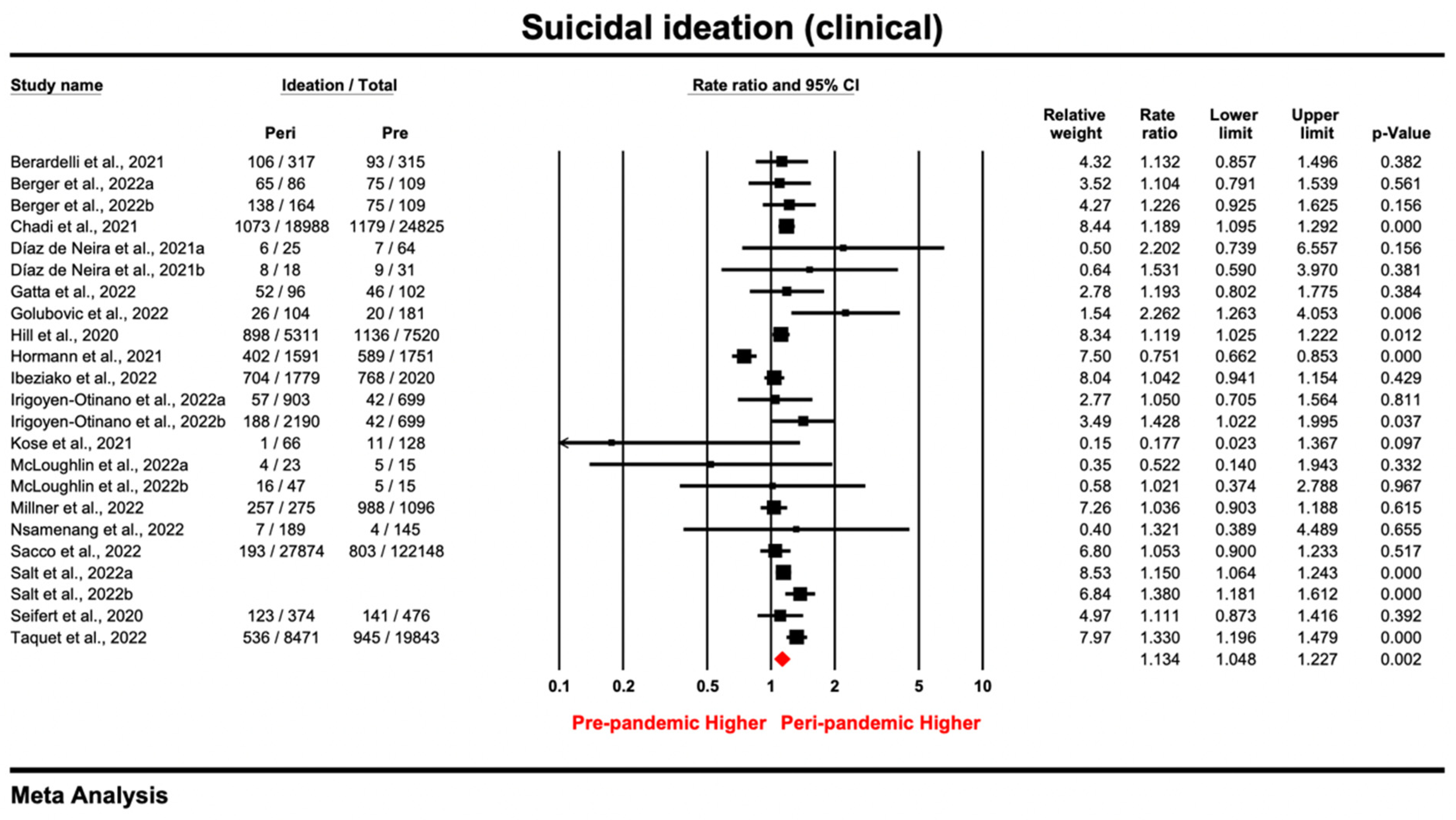

3.2.3. Clinical Samples

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Suicide Attempt for Non-Clinical and Clinical Samples

3.3.1. Overview

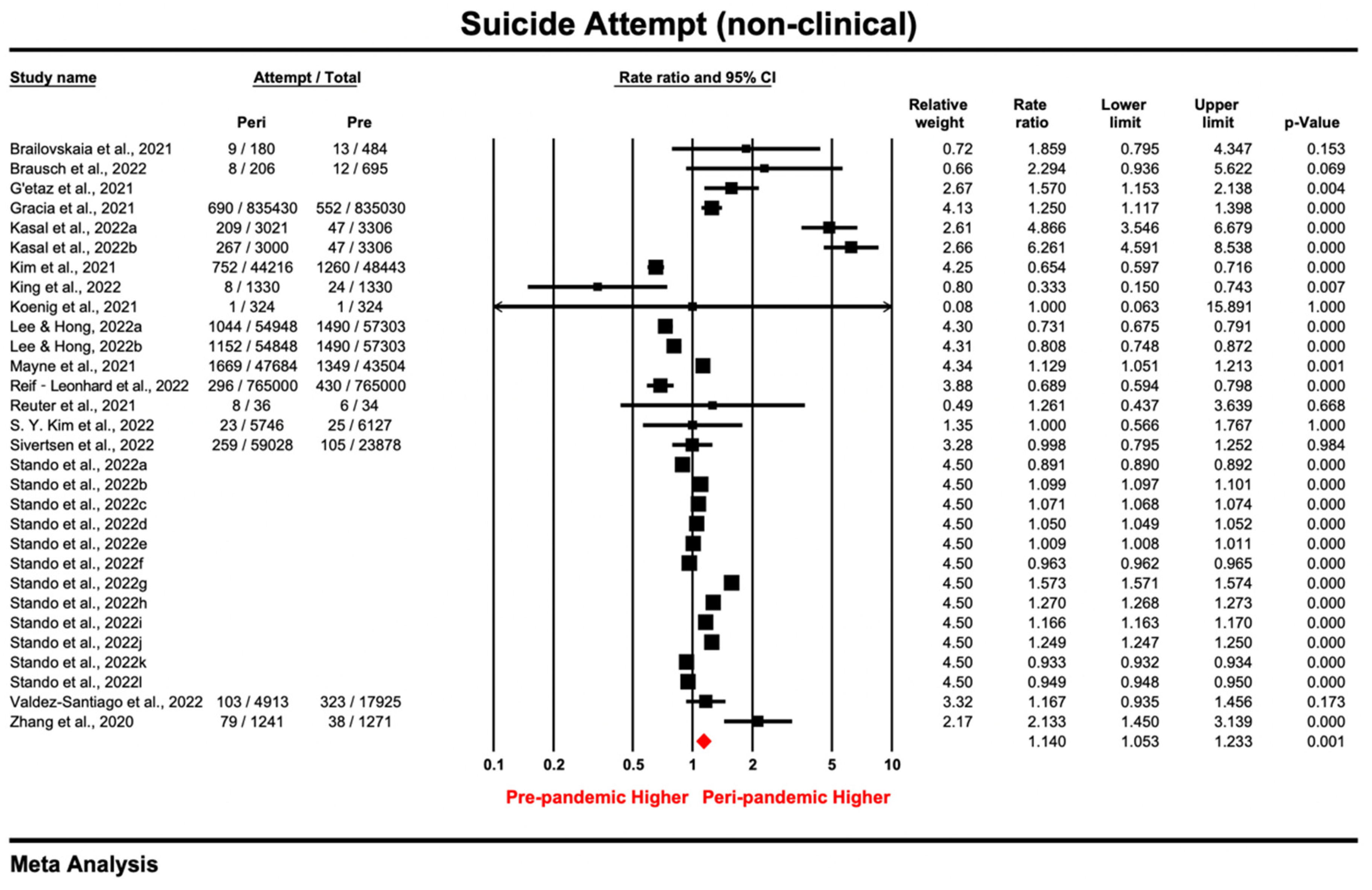

3.3.2. Non-Clinical Samples

3.3.3. Clinical Samples

3.4. Meta-Analysis for Death by Suicide

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devitt, P. Can we expect an increased suicide rate due to COVID-19? Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Begum, N.; Saini, A.; Wang, S.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious disease epidemics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahil, K.; Cheaito, M.A.; El Hayek, R.; Nofal, M.; El Halabi, S.; Kudva, K.G.; Pereira-Sanchez, V.; El Hayek, S. Suicide during COVID-19 and other major international respiratory outbreaks: A systematic review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2021, 56, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaune, E.; Samuel, M.; Oh, H.; Poulet, E.; Brunelin, J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic rapid review. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zortea, T.C.; Brenna, C.T.; Joyce, M.; McClelland, H.; Tippett, M.; Tran, M.M.; Arensman, E.; Corcoran, P.; Hatcher, S.; Heisel, M.J. The impact of infectious disease-related public health emergencies on suicide, suicidal behavior, and suicidal thoughts: A systematic review. Crisis J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2021, 42, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Hawton, K.; John, A.; Kapur, N.; Khan, M.; O’Connor, R.C.; Pirkis, J.; Caine, E.D. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Subedi, K.; Acharya, P.; Ghimire, S. Association between COVID-19 pandemic and the suicide rates in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasal, A.; Kuklová, M.; Kågström, A.; Winkler, P.; Formánek, T. Suicide risk in individuals with and without mental disorders before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of three nationwide cross-sectional surveys in Czechia. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifman, J.; Ettman, C.K.; Dean, L.; Barry, C.; Galea, S. Economic precarity, social isolation, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, S.; Joensen, A.; Andersen, P.K.; Madsen, T.; Strandberg-Larsen, K. Self-injury, suicidal ideation and -attempt and eating disorders in young people following the initial and second COVID-19 lockdown. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.-R.; Park, B.; Choi, H.G. Comparison of stress and suicide-related behaviors among Korean youths before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2136137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Lui, L.M.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Ho, R.; Gill, H.; Mansur, R.B.; Teopiz, K.; Liao, Y.; Lu, C.; Subramaniapillai, M. Suicide reduction in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons informing national prevention strategies for suicide reduction. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, L.; Richards, N.; Ibrahim, S.; Turnbull, P.; Rodway, C.; Kapur, N. Suicide in England in the COVID-19 pandemic: Early observational data from real time surveillance. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2021, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.; Kohls, E.; Moessner, M.; Lustig, S.; Bauer, S.; Becker, K.; Thomasius, R.; Eschenbeck, H.; Diestelkamp, S.; Gillé, V. The impact of COVID-19 related lockdown measures on self-reported psychopathology and health-related quality of life in German adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 32, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, J.; Meissner, C.; Birkenstock, A.; Bleich, S.; Toto, S.; Ihlefeld, C.; Zindler, T. Peripandemic psychiatric emergencies: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients according to diagnostic subgroup. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipe, D.; John, A.; Padmanathan, P.; Eyles, E.; Dekel, D.; Higgins, J.P.; Bantjes, J.; Dandona, R.; Macleod-Hall, C.; McGuinness, L.A. Suicide and self-harm in low-and middle-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Gunnell, D.; Shin, S.; Del Pozo-Banos, M.; Arya, V.; Aguilar, P.A.; Appleby, L.; Arafat, S.Y.; Arensman, E.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Suicide numbers during the first 9–15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-existing trends: An interrupted time series analysis in 33 countries. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 51, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersia, M.; Koumantakis, E.; Berchialla, P.; Charrier, L.; Ricotti, A.; Grimaldi, P.; Dalmasso, P.; Comoretto, R.I. Suicide spectrum among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Eyles, E.; Webb, R.; Okolie, C.; Schmidt, L.; Arensman, E.; Hawton, K.; O’Connor, R.; Kapur, N.; Moran, P.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: Update of living systematic review. F1000Research 2021, 9, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirathna, M.L.; Nandasena, H.M.R.K.G.; Atapattu, A.M.M.P.; Weerasekara, I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicidal attempts and death rates: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, J.P.; Smith, M.M.; Sherry, S.B.; Hewitt, P.L.; Stewart, S.H. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Tunmore, J.; Ali, M.W.; Ayub, M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Pirkis, J.; Gunnell, D.; Appleby, L.; Morrissey, J. Trends in suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 371, m4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Public Health Action for the Prevention of Suicide: A Framework. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75166/?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Wasserman, I.M. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1992, 22, 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A.; Gunnell, D.; O’Connor, R.C.; Oquendo, M.A.; Pirkis, J.; Stanley, B.H. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckler, D.; Basu, S.; Suhrcke, M.; Coutts, A.; McKee, M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: An empirical analysis. Lancet 2009, 374, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coentre, R.; Góis, C. Suicidal ideation in medical students: Recent insights. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.A. Suicide and suicidal behaviors in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A systematic review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Schoot, R.; de Bruin, J.; Schram, R.; Zahedi, P.; de Boer, J.; Weijdema, F.; Kramer, B.; Huijts, M.; Hoogerwerf, M.; Ferdinands, G. An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, R.; Bjarnason, E.; Runeson, P. A machine learning approach for semi-automated search and selection in literature studies. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Karlskrona, Sweden, 15–16 June 2017; pp. 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. GDP per Capita (Current US$). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Statista. Global Economic Indicators—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/5442/global-economic-indicators/#topicHeader__wrapper (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/national-accounts/australian-national-accounts-national-income-expenditure-and-product/latest-release (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics. GDP by City. Available online: http://tj.jiangsu.gov.cn/2022/nj02/nj0212.htm (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Bloomberg. The COVID Resilience Ranking The Best and Worst Places to Be as World Enters Next COVID Phase. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-resilience-ranking/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- University of Oxford. COVID-19 GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TRACKER. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/covid-19-government-response-tracker (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Large, M.M.; Nielssen, O.B. Suicide in Australia: Meta-analysis of rates and methods of suicide between 1988 and 2007. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copas, J.; Shi, J.Q. Meta-analysis, funnel plots and sensitivity analysis. Biostatistics 2000, 1, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldston, D.B. Assessment of Suicidal Behaviors and Risk among Children and Adolescents; National Institute of Mental Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, L.O.; Győri, D.; Komáromy, D.; Meszaros, G.; Szentiványi, D.; Balazs, J. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: The role of life events in clinical and non-clinical populations of adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Situation. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Morillo, D.; Haro, J.; Olaya, B.; Lara, E.; Miret, M. Changes in depression and suicidal ideation under severe lockdown restrictions during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A longitudinal study in the general population. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bountress, K.E.; Cusack, S.E.; Conley, A.H.; Aggen, S.H.; Group, S.f.S.W.; Vassileva, J.; Dick, D.M.; Amstadter, A.B. The COVID-19 pandemic impacts psychiatric outcomes and alcohol use among college students. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2022, 13, 2022279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Mann, A.J.; Tull, M.T. Suicidal ideation among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Identifying at-risk subgroups. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 302, 114034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horita, R.; Nishio, A.; Yamamoto, M. Lingering effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of first-year university students in Japan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rackoff, G.N.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Shin, K.E.; Zainal, N.H.; Schwob, J.T.; Eisenberg, D.; Wilfley, D.E.; Taylor, C.B.; Newman, M.G. College mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a nationwide survey. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichter, B.; Hill, M.L.; Na, P.J.; Kline, A.C.; Norman, S.B.; Krystal, J.H.; Southwick, S.M.; Pietrzak, R.H. Prevalence and trends in suicidal behavior among US military veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Paul, L.; Paul, W. The changes of suicidal ideation status among young people in Hong Kong during COVID-19: A longitudinal survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tong, Y.; Liu, N.H. Mental health problems among hotline callers during the early stage of COVID-19 pandemic. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Häberling, I.; Lustenberger, A.; Probst, F.; Franscini, M.; Pauli, D.; Walitza, S. The mental distress of our youth in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadi, N.; Spinoso-Di Piano, C.; Osmanlliu, E.; Gravel, J.; Drouin, O. Mental Health–related emergency department visits in adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicentric retrospective study. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Pollock, N.J.; Contreras, G.; Tonmyr, L.; Thompson, W. Prevalence of suicidal ideation among adults in Canada: Results of the second Survey on COVID-19 and mental health. Health Rep. 2022, 33, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, A.; Abdalla, A.; Gonzalez, J.; Freyne, A.; Asghar, M.; Ferguson, Y. Locked in and locked out: Sequelae of a pandemic for distressed and vulnerable teenagers in Ireland: Post-COVID rise in psychiatry assessments of teenagers presenting to the emergency department out-of-hours at an adult Irish tertiary hospital. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, D.L.; Probst, M.A.; Schultebraucks, K.; Greene, M.C.; Chang, B.P. Evaluation of emergency department visits for mental health complaints during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2022, 3, e12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, A.K.S.; Stene-Larsen, K.; Gustavson, K.; Hotopf, M.; Kessler, R.C.; Krokstad, S.; Skogen, J.C.; Øverland, S.; Reneflot, A. Prevalence of mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicides in the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway: A population-based repeated cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2021, 4, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, T.; Girardi, P.; Clerici, M.; Conca, A.; Creati, C.; Di Cicilia, G.; Ducci, G.; Durbano, F.; Maci, C.; Maone, A. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on admissions to general hospital psychiatric wards in Italy: Reduced psychiatric hospitalizations and increased suicidality. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 110, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gétaz, L.; Wolff, H.; Golay, D.; Heller, P.; Baggio, S. Suicide attempts and Covid-19 in prison: Empirical findings from 2016 to 2020 in a Swiss prison. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E.C.; Thomas, S.A.; Burke, T.A.; Nesi, J.; MacPherson, H.A.; Bettis, A.H.; Kudinova, A.Y.; Affleck, K.; Hunt, J.; Wolff, J.C. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents pre-and post-COVID-19: A historical chart review and examination of contextual correlates. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valdez-Santiago, R.; Villalobos, A.; Arenas-Monreal, L.; González-Forteza, C.; Hermosillo-de-la-Torre, A.E.; Benjet, C.; Wagner, F.A. Comparison of suicide attempts among nationally representative samples of Mexican adolescents 12 months before and after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 298, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Dash, R.K.; Das, A.; Hota, M.; Mohapatra, C.; Dash, S. An Epidemiological Study of Cut Throat Injury During COVID-19 Pandemic in a Tertiary Care Centre. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 74, 2764–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Bermejo, A.F.; Ortega-Pérez, J.; Frontera-Juan, G.; Homar-Amengual, C.; Barceló-Martín, B.; Puiguriguer-Ferrando, J. Acute poisoning among patients attended to in an emergency department: From the pre-pandemic period to the new normality. Rev. Clínica Española Engl. Ed. 2022, 222, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidancı, İ.; Taşar, M.A.; Akıntuğ, B.; Fidancı, İ.; Bulut, İ. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric emergency service. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14398. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, R.; Pamias, M.; Mortier, P.; Alonso, J.; Pérez, V.; Palao, D. Is the COVID-19 pandemic a risk factor for suicide attempts in adolescent girls? J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habu, H.; Takao, S.; Fujimoto, R.; Naito, H.; Nakao, A.; Yorifuji, T. Emergency dispatches for suicide attempts during the COVID-19 outbreak in Okayama, Japan: A descriptive epidemiological study. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 511–517. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, D.M.; Kwon, M.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Wee, J.H.; Choi, H.G. Depression, Stress, and Suicide in Korean Adults before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Data from the Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańdo, J.; Czabański, A.; Fechner, Ż.; Baum, E.; Andriessen, K.; Krysińska, K. Suicide and Attempted Suicide in Poland before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic between 2019 and 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, V.; Page, A.; Spittal, M.J.; Dandona, R.; Vijayakumar, L.; Munasinghe, S.; John, A.; Gunnell, D.; Pirkis, J.; Armstrong, G. Suicide in India during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 307, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Yang, C.-T.; Pinkney, E.; Yip, P.S.F. Suicide trends varied by age-subgroups during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2022, 121, 1174–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-Luque, A.; Pemau, A.; Perez-Sola, V.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Suicide mortality in Spain in 2020: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. De Psiquiatr. Y Salud Ment. 2022, 587, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, J.S.; Shah, S.B.; Du, C.; Li, S.-X.; Lin, Z.; Krumholz, H.M. Suicide deaths during the COVID-19 stay-at-home advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2034273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, R.M.; Narváez, F.; Leske, S.; Troya, M.I.; Analuisa-Aguilar, P.; Spittal, M.J.; Gunnell, D. Police-reported suicides during the first 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ecuador: A time-series analysis of trends and risk factors until June 2021. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 14, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, P.S.; Bergmans, R.S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on temporal patterns of mental health and substance abuse related mortality in Michigan: An interrupted time series analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 10, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.O.; Li, L. State-level data on suicide mortality during COVID-19 quarantine: Early evidence of a disproportionate impact on racial minorities. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113629. [Google Scholar]

- Page, A.; Spittal, M.J. A decline in Australian suicide during COVID-19? A reflection on the 2020 cause of death statistics in the context of long-term trends. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2022, 9, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacio-Mejía, L.S.; Hernández-Ávila, J.E.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; Dyer-Leal, D.; Barranco, A.; Quezada-Sánchez, A.D.; Alvarez-Aceves, M.; Cortés-Alcalá, R.; Fernández-Wheatley, J.L.; Ordoñez-Hernández, I. Leading causes of excess mortality in Mexico during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020–2021: A death certificates study in a middle-income country. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 13, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, D.; Genuneit, J.; Bachmann, C.J. Suicides in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic—An analysis based on data from 11 million inhabitants, 2017-2021. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2022, 119, 502–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalska, A.; Syrkiewicz-Świtała, M. COVID-19 and Mortality, Depression, and Suicide in the Polish Population. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 854028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rück, C.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Malki, K.; Adler, M.; Flygare, O.; Runeson, B.; Sidorchuk, A. Will the COVID-19 pandemic lead to a tsunami of suicides? A Swedish nationwide analysis of historical and 2020 data. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stene-Larsen, K.; Raknes, G.; Engdahl, B.; Qin, P.; Mehlum, L.; Strom, M.S.; Reneflot, A. Suicide trends in Norway during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A register-based cohort study. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Okamoto, S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Huang, C.; Wang, L.; Hua, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y. Analysis of Injury Death of Suzhou During COVID-19 Epidemic. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 16, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Nam, H.J.; Jhon, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.W. Trends in suicide deaths before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Sarubbi, S.; Rogante, E.; Cifrodelli, M.; Erbuto, D.; Innamorati, M.; Lester, D.; Pompili, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide ideation and suicide attempts in a sample of psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Teismann, T.; Friedrich, S.; Schneider, S.; Margraf, J. Suicide ideation during the COVID-19 outbreak in German university students: Comparison with pre-COVID 19 rates. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 6, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, M.; Raffagnato, A.; Mason, F.; Fasolato, R.; Traverso, A.; Zanato, S.; Miscioscia, M. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of paediatric patients admitted to a neuropsychiatric care hospital in the COVID-19 era. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.M.; Rufino, K.; Kurian, S.; Saxena, J.; Saxena, K.; Williams, L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020029280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörmann, C.; Bandli, A.; Bankwitz, A.; De Bardeci, M.; Rüesch, A.; De Araujo, T.V.; Seifritz, E.; Kleim, B.; Olbrich, S. Suicidal ideations and suicide attempts prior to admission to a psychiatric hospital in the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Interrupted time-series analysis to estimate the impact of the lockdown and comparison of 2020 with 2019. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, N.; Pickett, W.; Rivera, D.; Byun, J.; Li, M.; Cunningham, S.; Duffy, A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of first-year undergraduate students studying at a major Canadian university: A successive cohort study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayne, S.L.; Hannan, C.; Davis, M.; Young, J.F.; Kelly, M.K.; Powell, M.; Dalembert, G.; McPeak, K.E.; Jenssen, B.P.; Fiks, A.G. COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021051507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, P.R.; Forster, B.L.; Kruger, B.J. A longitudinal study of the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on students’ health behavior, mental health and emotional well-being. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, B.; Knapstad, M.; Petrie, K.; O’Connor, R.; Lønning, K.J.; Hysing, M. Changes in mental health problems and suicidal behaviour in students and their associations with COVID-19-related restrictions in Norway: A national repeated cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. Incidence and outcomes of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Psychiatry 2022, 220, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brausch, A.M.; Whitfield, M.; Clapham, R.B. Comparisons of mental health symptoms, treatment access, and self-harm behaviors in rural adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de Neira, M.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; García Murillo, L.; Pérez-Balaguer, A.; Mallol, L.; Forti, A.; Del Sol, P.; Palanca, I. Demand analysis of a psychiatric emergency room and an adolescent acute inpatient unit in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Madrid, Spain. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 557508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubovic, S.T.; Zikic, O.; Nikolic, G.; Kostic, J.; Simonovic, M.; Binic, I.; Gugleta, U. Possible impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on suicide behavior among patients in Southeast Serbia. Open Med Wars 2022, 17, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibeziako, P.; Kaufman, K.; Scheer, K.N.; Sideridis, G. Pediatric Mental Health Presentations and Boarding: First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen-Otiñano, M.; Nicolau-Subires, E.; González-Pinto, A.; Adrados-Pérez, M.; Buil-Reiné, E.; Ibarra-Pertusa, L.; Albert-Porcar, C.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Sánchez-Cazalilla, M.; Torterolo, G.; et al. Characteristics of patients treated for suicidal behavior during the pandemic in a psychiatric emergency department in a Spanish province. Rev. De Psiquiatr. Y Salud Ment. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, S.; Inal-Kaleli, I.; Senturk-Pilan, B.; Cakcak, E.; Ucuncu, B.; Ozbaran, B.; Erermis, S.; Isik, H.; Saz, E.U.; Bildik, T. Effects of a pandemic on child and adolescent psychiatry emergency admissions: Early experiences during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry 2021, 61, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Hong, J.S. Short- and Long-Term Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Suicide-Related Mental Health in Korean Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millner, A.J.; Zuromski, K.L.; Joyce, V.W.; Kelly, F.; Richards, C.; Buonopane, R.J.; Nash, C.C. Increased severity of mental health symptoms among adolescent inpatients during COVID-19. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2022, 77, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsamenang, S.A.; Gutierrez, C.A.; Manayathu Jones, J.; Jenkins, G.; Tibelius, S.A.; Digravio, A.M.; Chamas, B.; Ewusie, J.E.; Geddie, H.; Punthakee, Z.; et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the mental and physical health of children enrolled in a paediatric weight management clinic. Paediatr. Child Health Can. 2022, 27, S72–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salt, E.; Wiggins, A.T.; Cerel, J.; Hall, C.M.; Ellis, M.; Cooper, G.L.; Adkins, B.W.; Rayens, M.K. Increased rates of suicide ideation and attempts in rural dwellers following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Rural. Health 2023, 39, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Fang, J.; Wan, Y.; Tao, F.; Sun, Y. Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2021482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reif-Leonhard, C.; Lemke, D.; Holz, F.; Ahrens, K.F.; Fehr, C.; Steffens, M.; Grube, M.; Freitag, C.M.; Kolzer, S.C.; Schlitt, S.; et al. Changes in the pattern of suicides and suicide attempt admissions in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, D.; Papsdorf, R.; Uhlig, K.; Vasilache, A.; Putnam, K.; Von Klitzing, K. Trends in suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in a major German city. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Huang, X.; Musacchio, K.M.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saricali, M.; Satici, S.A.; Satici, B.; Gocet-Tekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Fear of COVID-19, mindfulness, humor, and hopelessness: A multiple mediation analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel-Heller, S.; Richter, D. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of the general public: Is there a tsunami of mental disorders? Psychiatr. Prax. 2020, 47, 452–456. [Google Scholar]

- Barberis, N.; Cannavò, M.; Cuzzocrea, F.; Verrastro, V. Suicidal behaviours during COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2022, 19, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, M.É.; Lane, R.I.; Petrosky, E.; Wiley, J.F.; Christensen, A.; Njai, R.; Weaver, M.D.; Robbins, R.; Facer-Childs, E.R.; Barger, L.K. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, B.A.; Burke, T.A.; Jacobucci, R.; McClure, K. Preliminary investigation of the association between COVID-19 and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the US. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 134, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, R. An Observational Analysis of Suicidal Deaths during COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown at Lucknow, India. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2020, 14, 445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R.; Siwakoti, S.; Singh, S.; Shrestha, A.P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide and self-harm among patients presenting to the emergency department of a teaching hospital in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-J.; Ko, N.-Y.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wang, P.-W.; Chang, Y.-P.; Yen, C.-F.; Lu, W.-H. COVID-19-related factors associated with sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts among the Taiwanese public: A Facebook survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.; Prinstein, M.J.; Clark, L.A.; Rottenberg, J.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Albano, A.M.; Aldao, A.; Borelli, J.L.; Chung, T.; Davila, J. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Van Heeringen, K. The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, S. Is It Possible to Accurately Forecast Suicide, or Is Suicide a Consequence of Forecasting Errors? Thesis, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. 2014. Available online: https://psychology.nottingham.ac.uk/staff/ddc/c8cxpa/further/Dissertation_examples/Joy_14.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemball, R.S.; Gasgarth, R.; Johnson, B.; Patil, M.; Houry, D. Unrecognized suicidal ideation in ED patients: Are we missing an opportunity? Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2008, 26, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carison, A.; Babl, F.E.; O’Donnell, S.M. Increased paediatric emergency mental health and suicidality presentations during COVID-19 stay at home restrictions. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2022, 34, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.R.; Kurdyak, P.; Stukel, T.A.; Strauss, R.; Fu, L.; Guan, J.; Fiksenbaum, L.; Cohen, E.; Guttmann, A.; Vigod, S. Utilization of physician-based mental health care services among Children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, e216298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Bergen, H.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Cooper, J.; Steeg, S.; Kapur, N. Epidemiology and nature of self-harm in children and adolescents: Findings from the multicentre study of self-harm in England. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 21, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.D. Fluid vulnerability theory: A cognitive approach to understanding the process of acute and chronic suicide risk. In Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 355–368. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Country | Study Design | Population Type | Sample Size | Participant Characteristic | Time Range | Outcome | Measurement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age/Age Group | Female% | Pre-Pandemic Period | Peri-Pandemic Period | |||||||

| Acharya et al., 2022 [69] | India | Retrospective | Indoor Patients With Cut Throat Injury | Pre (10); Peri (14) | 25 (N = 17); 35 (N = 2); 45 (N = 4); 55 (N = 1) | 4.16% | Sept. 1st, 2019–Feb. 28th, 2020 | Mar. 1st–Aug. 31st for 2020 | Attempt | Diagnosis (Identified by tentative cut mark) |

| An et al., 2022 [58] | China | Retrospective | Hotline Callers | Pre (4940); Peri (5550) | Pre: <30 (76%), >30 (24%); Peri: <30 (74.4%), >30 (25.6%) | Pre (52.7%); Peri (60.6%) | Jan. 21st–Jun. 30th for 2019 | Jan. 21st–Jun. 30th for 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (Assessed by asking the caller Have you repeatedly thought about taking your life or hurting yourself in the last two weeks? Or have you felt too tired and without meaning to continue to live in the last two weeks? |

| Ayuso-Mateos et al., 2021 [51] | Spain | Longitudinal | General Population | 1103 | 54.82 | 64.8% | Jun. 17th 2019–Mar. 14th 2020 | May 21st 2020–Jun. 30th 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (An item of Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Whether the participant had had suicidal thoughts in the previous 12 months/30 days) |

| Berardelli et al., 2021 [92] | Italy | Retrospective | Psychiatric Patients | Pre (315); Peri (317) | 42.25 | 49.2% | May 2019–Mar. 9th 2020 | Mar. 10th–Dec. 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (definition: thoughts about wishing to be dead or active thoughts of wanting to end one’s life) Diagnosis (Definition: a non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with an implicit or explicit intent to die; the behavior may or may not result in injury, and the intensity may vary, but the decision to act out the lethal intent must be present) |

| Berger et al., 2022 [59] | Switzerland | Retrospective | Emergency Psychiatric Adolescent Patients | Pre (109); Peri 1 (86); Peri 2 (164) | Pre (14.89); Peri 1 (14.81); Peri 2 (14.41) | Pre (56.6%); Peri 1 (57%); Peri 2 (64.2%) | Mar. 1st–Apr. 30th for 2019 | Mar. 1st–Apr. 30th for 2020; Mar. 1st–Apr. 30th for 2021 | Ideation | Diagnosis (Medical record) |

| Boldrini et al., 2021 [65] | Italy | Retrospective | Psychiatric Patients | Pre (3270); Peri 1 (589); Peri 2 (691) | 45.4 | 52.70% | March 1st–Jun. 30th for 2018–2019 | Mar. 1st–Apr. 30th for 2020; May 1st–Jun. 30th for 2020 | Attempt | Diagnosis (Medical record) |

| Bountress et al., 2022 [52] | United State | Longitudinal | College Students | 897 | 18.49 (Baseline) | 78.6% | Spring of 2019 | May 7th 2020–Jul. 17th 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (a Symptom Checklist-90 Revised: participants answered whether they had thought about killing themselves by yes or no). |

| Brailovskaia et al., 2021 [93] | Germany | Repeated Cross-sectional | College Students | Pre: 2016 (105); 2017 (117); 2018 (108); 2019 (154); Peri: 2020 (180) | Pre: 2016 (22.51); 2017 (22.53); 2018 (20.59); 2019 (21.98); Peri: 2020 (21.33) | Pre: 2016 (81.9%); 2017 (78.6%); 2018 (73.1%); 2019 (84.4%); Peri: 2020 (73.3%) | Oct.–Dec. for 2016–2019 | Oct.–Dec. for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (a Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised: How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year?) Self-report (A Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised: Have you ever attempted suicide, and really hoped to die?) |

| Brausch et al., 2022 [102] | United State | Repeated Cross-sectional | High School Students | Pre (695); Peri (206) | Pre (15.5); Peri (15.6) | Pre (54.8%); Peri (57.8%) | 2018–2019 | 2020–2021 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview—short form; past year) |

| Caballero-Bermejo et al., 2022 [70] | Spain | Retrospective | Emergency Patients | Pre (528); Peri 1 (299); Peri 2 (355) | Pre (31.4); Peri 1(41.3); Peri 2 (38.3) | Pre (41.5%); Peri 2 (33.1%); Peri 2 (41.4%) | Jun.–Jul. for 2019 | Jun.–Jul. for 2020; Jun.–Jul. for 2021 | Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Chadi et al., 2021 [60] | Canada | Retrospective | Emergency Adolescent Patients | Pre (24,824.5); Peri (18,988) | -- | -- | 2018–2019 | 2020 | Ideation | Diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition) |

| Danielsen et al., 2022 [11] | Denmark | Longitudinal | Young People | Pre (27,441); Peri (7597) | 20.7 (Wave 8) | Pre (56%); Peri (67%) | Jan. 1st 2018–Mar. 11th for 2020 | Mar. 12th 2020–Mar. 1st 2021 | Ideation | Self-report (Have you thought about taking your own life, even though you would not do it, within the last year?) |

| Díaz de Neira et al., 2021 [103] | Italy | Retrospective | Emergency Adolescent Patients; Psychiatric Adolescent Inpatients | Emergency sample: Pre (64); Peri (25); Psychiatric sample: Pre (31); Peri (18) | Emergency sample: Pre (14.2); Peri (15.36); Psychiatric Sample: Pre (15.55); Peri (15.17) | Emergency sample: Pre (62.5%); Peri (72%); Psychiatric Sample: Pre (64.5%); Peri (72.2%) | 2019 | 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Ettman et al., 2020 [10] | United State | Repeated Cross-sectional | General Population | Pre (5085); Peri (1415) | Pre (46.57); Peri (45.62) | Pre (51.3%); Peri (50%) | 2017–2018 | Mar. 31st 2020–Apr. 13th 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (Item 9 of the Patient Heath Questionarie-9: Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way over the past two weeks?) |

| Fidancı et al., 2021 [71] | Turkey | Retrospective | Pediatric Emergency Adolescents | Pre (55,678); Peri (19,061) | Pre (8.11); Peri (8.58) | Pre (47.6%); Peri (48.9%) | Apr.–Oct. for 2019 | Apr.–Oct. for 2020 | Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Gatta et al., 2022 [94] | Italy | Repeated Cross-sectional | Psychiatric Adolescent Patients | Pre (102); Peri (96) | Pre (13.2); Peri (13.8) | Pre (63.7%); Peri (65.6%) | Feb. 2019–Feb. 2020 | Mar. 2020–Mar. 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| G’etaz et al., 2021 [66] | Switzerland | Retrospective | Prisoners | -- | -- | -- | 2016–2019 | 2020 | Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Golubovic et al., 2022 [104] | Serbia | Retrospective | Psychiatric Adult patients | Pre (181); Peri (104) | 40.58 | 41.55% | May–Aug. for 2018–2019 | May–Aug. for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (definition: thoughts about wishing to be dead or active thoughts of wanting to end one’s life) Diagnosis (definition: nonfatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with an implicit or explicit intent to die). |

| Gracia et al., 2021 [72] | Spain | Retrospective | Adolescent | Pre (835,030); Peri (835,430) | -- | -- | Mar. 2019–Mar. 2020) | Mar. 2020–Mar. 2021 | Attempt | Diagnosis (Six-item suicidality module of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) |

| Gratz et al., 2021 [53] | United State | Repeated Cross-Sectional | College Students | Pre1 (539); Pre2 (723); Peri (438) | Pre1 (19.39); Pre2 (19.26); Peri (19.53) | Pre1 (69.2%); Pre2 (64.9%); Peri (61.9%) | Fall 2014; Fall 2013 | Fall 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (pre: How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year?; peri: Have you had thoughts of killing yourself in the past year?). |

| H. Kim et al., 2022 [55] | United State | Repeated Cross-Sectional Study | College Students | Pre (3643); Peri (4970) | Pre (18.85); Peri (19.5) | Pre (73.1%); Peri (69.7%) | Oct. 7th–Dec. 1st for 2019 | Mar. 2nd–May 9th for 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (Item 9 of the Patient Heath Questionarie-9: Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way over the past two weeks?) |

| Habu et al., 2021 [73] | Japan | Retrospective | Emergency Call Patients | Pre (33,594); Peri (14,176) | Pre (60.1); Peri (62.8) | Pre (48.7%); Peri (49.2%) | Mar.–Aug. for 2018–2019 | Mar.–Aug. for 2020 | Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Hill et al., 2020 [95] | United State | Retrospective | Pediatric Patients | Ideation: Pre (7520); Peri (5311) Attempt: Pre (7510); Peri (5302) | 14.52 | 59% | Jan.–Jul. for 2019 | Jan.–Jul. for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale) |

| Horita et al., 2022 [54] | Japan | Repeated Cross-Sectional | College Students | Pre (440); Peri 1 (766); Peri 2 (738) | -- | Pre (51.4%); Peri 1 (45.3%); Peri 2 (49.5%) | Apr. 15th–May 31st for 2019 | Apr. 20th–May 31st for 2020; Apr. 10th–May 31st for 2021 | Ideation | Self-report (an item of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms: I have had thoughts of ending my life in the past 2 weeks). |

| Hörmann et al., 2021 [96] | Switzerland | Retrospective | Psychiatric Patients | Pre (1751); Peri (1591) | Pre: <30 (22.8%), 30–59 (61.55), 60+ (15.7%); Peri: <30 (24.4%), 30–59 (59.8%), 60+ (15.8%) | Pre (46.2%); Peri (46.7%) | Mar. 13th–May 11th for 2019 | Mar. 13th–May 11th for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Methodik und Dokumentation in der Psychiatrie System) |

| Ibeziako et al., 2022 [105] | United State | Retrospective | Pediatric Psychiatric Patients | Pre (2020); Peri (1779) | Pre (8.11); Peri (8.58) | Pre (55.9%); Peri (65.8%) | Mar. 2019–Feb. 2020 | Mar. 2020–Feb. 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition) |

| Irigoyen-Otiñano et al., 2022 [106] | Spain | Retrospective | Psychiatric Emergency Patients | Pre (699); Peri 1 (903); Peri 2 (2190) | Pre (43.6); Peri 1 (39.6); Peri 2 (37.1) | Pre (60%); Peri 1 (59.2%); Peri 2 (60.5%) | Jan. 13th–Mar. 14th for 2020 | Mar. 15th–Jun. 20th for 2020; Oct. 25th 2020–May 9th 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) Diagnosis (definition: a self-inflicted, potentially injurious behavior with a nonfatal outcome for which there is evidence, either explicit or implicit, of intent to die) |

| Kasal et al., 2022 [9] | Czechia | Repeated Cross-Sectional | General Population | Pre (3306); Peri 1(3021); Peri 2 (3000) | Pre (48.82); Peri 1 (46.84); Peri 2 (46.16) | Pre (53.7%); Peri 1 (52.3%); Peri 2 (51.1%) | Nov. 2017 | May 2020; Nov. 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Items of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview: Think that you would be better off dead or wish you were dead? Want to harm yourself? Think about suicide? Have a suicide plan?) Self-report (Items of Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview: Attempt suicide? Did you ever make a suicide attempt?) |

| Kim et al., 2021 [12] | South Korea | Repeated Cross-Sectional | Adolescents | Pre (48,443); Peri (44,216) | Pre (15); Peri (15.1) | Pre (48.7%); Peri (47.5%) | Jun. 3rd–Jul. 12th for 2019 | Aug. 3rd–Nov. 13th for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (single question: Participants were asked if they had considered suicide seriously within the past 12 months) Self-report (single question of if they had attempted suicide within the past 12 months) |

| King et al., 2022 [97] | Canada | Longitudinal (Matched Sample) | College Students | 1330 | Pre (18.5); Peri (18.8) | 67.2% | 2018–2019 | 2020–2021 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale) |

| Knudsen et al., 2021 [64] | Norway | Repeated Cross-Sectional | General Population | Pre (563); Peri 1 (691); Peri 2 (530); Peri 3 (370); | Pre (38.3); Peri 1(39.4); Peri 2 (39.2); Peri 3 (39.1) | Pre (56.6%); Peri 1(62.3%); Peri 2 (61.2%); Peri 3 (64.1%) | Jan. 28th–Mar. 11th for 2020 | Mar. 12th–May 31st for 2020; Jun. 1st–Jul. 31st 2020; Aug. 1st -Sept. 18th 2020 | Ideation | Diagnosis (Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Thoughts of killing oneself or wishing one was dead during the 30 days before the interview) |

| Koenig et al., 2021 [15] | Germany | Longitudinal (Matched Sample) | Adolescents | 324 | 14.93 | 69.3% | Nov. 26th 2018–Mar. 13th 2020 | Mar. 18th–Aug. 29th for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Paykel Suicide Scale) |

| Kose et al., 2021 [107] | Turkey | Retrospective | Psychiatry Emergency Adolescents | Pre (128); Peri (66) | -- | -- | Mar.–Jun. for 2019 | Mar.–Jun. for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Lee and Hong, 2022 [108] | South Korea | Repeated Cross-Sectional | High School Students | Pre (57,303); Peri 1 (54,948); Peri2 (54,848) | Pre (15.08); Peri 1 (15.19); Peri2 (15.23) | Pre (48.2%); Peri 1 (48%); Peri2 (48.1%) | Jun.–Jul. for 2019 | Aug.–Nov. for 2020–2021 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (whether suicidal thoughts had occurred in the past 12 months) Self-report (whether suicide attempt had occurred in the past 12 months) |

| Liu et al., 2022 [61] | Canada | Repeated Cross-Sectional | General Population | Pre (57,034); Peri (5742) | Pre: 18–34 (28.4%), 35–64 (50.1%), 65+ (21.5%); Peri: 18–34 (24.8%), 35–64 (53%), 65+ (22.3%) | Pre (50.8%); Peri (50.7%) | Jan. 2nd–Dec. 24th for 2019 | Feb. 1–May 7 for 2021 | Ideation | Self-report (2021: have you seriously contemplated suicide since the COVID-19 pandemic began?; 2019: Have you ever seriously contemplated suicide and has this happened in the past 12 months?) |

| Mayne et al., 2021 [98] | United State | Repeated Cross-Sectional | Adolescents | Pre (43,504); Peri (47,684) | Pre (15.2); Peri (15.3) | Pre (49.3%); Peri (49.7%) | Jun.–Dec. for 2019 | Jun.–Dec. for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Has there been a time in the past month when you have had serious thoughts about ending your life?) Self-report (Have you ever, in your whole life, tried to kill yourself or made a suicide attempt?) |

| McLoughlin et al., 2022 [62] | Ireland | Retrospective | Psychiatric Emergency Adolescent Patients | Pre (15); Peri 1 (23); Peri 2 (47) | 16.5 | Pre (46.7%); Peri 1 (60%); Peri 2 (72%) | Mar.–May for 2019 | Mar.–May for 2020–2021 | Ideation | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Millner et al., 2022 [109] | United State | Retrospective | Pediatric Psychiatric Patients | Pre (1096); Peri (275) | Pre (15.82); Peri (15.13) | Pre (71.1%); Peri (88.7%) | April 2017 to March 12, 2020 | March 13, 2020 to April 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview Self-Report Version; past month). |

| Nichter et al., 2021 [56] | United State | Longitudinal | Military Veterans | 3078 | 63.2 | 8.4% | Nov. 18th 2019–Mar. 8th 2020 | Nov. 9th–Dec. 17th for 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (Item 2 of the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised: How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past years?) |

| Nsamenang et al., 2022 [110] | Canada | Retrospective | Pediatric Patients with Obesity | Pre (145); Peri (189) | Pre (11.9); Peri (11.5) | Pre (45.5%); Peri (47.1%) | Dec.15th 2019–Mar. 15th 2020 | Dec.15th 2020– Mar. 15th 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Reif-Leonhard et al., 2022 [113] | Germany | Retrospective | General Population | 765,000 | -- | -- | Mar.–Dec. 2019 | Mar.–Dec. 2020 | Attempt | Diagnosis (definition: deliberate self-harm with intend to die, irrespective of fatality probability) |

| Reuter et al., 2021 [99] | United State | Repeated Cross-Sectional | College Students | Ideation: Pre (619); Peri (491) Attempt: Pre (34); Peri (36) | Pre (20.3); Peri (20.6) | Pre (77.4%); Peri (83.8%) | Apr. 2018–Feb. 2020 | Nov. 2020–Apr. 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?) Self-report (Did you actually attempt suicide?) |

| S. Y. Kim et al., 2022 [74] | South Korea | Repeated Cross-Sectional | General Population | Pre (6127); Peri (5746) | Pre (51.7); Peri (52) | Pre (50.3%); Peri (50%) | Jan.–Dec. for 2019 | Jan.–Dec. for 2020 | Attempt | Self-report (Have you ever attempted suicide within 1 year?) |

| Sacco et al., 2022 [63] | United State | Retrospective | Emergency Department Patients | Pre (122,148); Peri (27,874) | -- | -- | Mar. 15th–Jul. 31 for 2017–2019 | Mar. 15th–Jul. 31st for 2020 | Ideation | Diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition) |

| Salt et al., 2022 [111] | United State | Retrospective | Adult Patients; Pediatric Patients | Pre (845,992); Peri (714,578) | -- | -- | Mar. 18th–Sept. 18th for 2019 | Mar. 18th–Sept. 18th for 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition) |

| Seifert et al., 2020 [16] | Germany | Retrospective | Psychiatric Patients | Pre (476); Peri (374) | Pre (44.48); Peri (43.4) | Pre (47.9%); Peri (39.3%) | Mar. 16th–May 24th for 2019 | Mar. 16th–May 24th for 2019 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Methodik und Dokumentation in der Psychiatrie System) |

| Sivertsen et al., 2022 [100] | Norway | Repeated Cross-Sectional | College Students | Pre 1 (8124); Pre 2 (13,663); Pre 3 (49,836); Peri (59,028) | Pre 1 (24.1); Pre 2 (23.55); Pre 3 (24.27); Peri (23.53) | Pre 1 (65.6%); Pre 2 (65.8%); Pre 3 (66.5%); Peri (69.1%) | Oct. 11th–Nov. 8th for 2010; Feb. 24th–Mar. 27th for 2014; Feb. 6th–Apr. 5th for 2018 | Mar. 1st–Apr. 6th for 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (an item of the depression subscale of HSCL-25: In the past 2 weeks, including today, how much have you been bothered by thoughts of ending your life?) Self-report (an item of the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Have you ever made an attempt to take your life, by taking an overdose of tablets or in some other way?) |

| Stańdo et al., 2022 [75] | Poland | Retrospective | General Population | -- | 13–24 (4556 million); 25–64 (20.714 million); 65+ (7.417 million) | -- | 2019 | 2020; 2021 | Attempt | Diagnosis (medical record) |

| Taquet et al., 2022 [101] | United State | Retrospective | Eating Disorder Adolescents Patients | Pre (19,843); Peri (8471) | Pre (16.34); Peri (16.25) | Pre (75.4%); Peri (78.1%) | Jan. 20th 2017–Jan. 19th 2020 | Jan. 20th 2020–Jan. 19th 2021 | Ideation Attempt | Diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition; code R45.851) Diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition; code T14.91) |

| Thompson et al., 2021 [67] | United State | Retrospective | Psychiatric Patients | Pre (196); Peri (142) | Pre (14.53); Peri (15.06) | Pre (--); Peri (45.8%) | Apr. 13th–Sept. 14th for 2019 | Apr. 13th–Sept. 14th for 2020 | Attempt | Self-report (Have you made any suicide attempts in the 7 days before you came to the hospital?) |

| Valdez-Santiago et al., 2022 [68] | Mexico | Repeated Cross-Sectional | Adolescents | Pre (17,925); Peri (4913) | -- | -- | Jul. 2018–Jun. 2019 | Aug.–Nov. for 2020 | Attempt | Self-report (Have you ever attempted to harm yourself or deliberately cut, intoxicated or hurt yourself in any way for the purpose of dying? (2) Was this in the last 12 months? |

| Zhang et al., 2020 [112] | China | Longitudinal | Primary School Students | Pre (1271); Peri (1241) | 12.6 | 40.7% | Nov. 2019 | May 2020 | Ideation Attempt | Self-report (Have you ever thought about killing yourself in the past 3 months?) Self-report (Have you ever tried to kill yourself in the past 3 months?) |

| Zhu et al., 2021 [57] | China | Longitudinal | High School Students | 1393 | 13.04 | 53.1% | Sept. 2019 | Jun. 2020 | Ideation | Self-report (Item 9 of the Patient Heath Questionarie-9: Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way over the past two weeks?) |

| Study | Region | Data Sources | Time Range | GDP (Peri/Pre) | Unemployment Rate (Peri/Pre) | Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Pandemic Period | Peri-Pandemic Period | ||||||

| Acharya et al., 2022 [8] | Nepal | Nepal Police Headquarter | Jul. 2017–Mar. 2020 (Jan.–Dec. 2019) * | Apr. 2020–Jun. 2021 (Apr. 2020–Mar. 2021) * | 0.98 | 1.52 | An overall increase in the monthly suicide rate was found during the pandemic months (Increase in rate = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.45). |

| Appleby et al., 2021 [14] | England (NHS sustainability and transformation partnerships region) | Real Time Surveillance (RTS) System | Apr.–Oct. for 2019 | Apr.–Oct. for 2020 | 0.98 | 1.14 | Comparison of the suicide rates after lockdown began in 2020 to those of the same months in 2019 showed no difference (IRR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.92–1.09). |

| Arya et al., 2022 [76] | India | National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) Data | 2010−2019 (2017) * | 2020 | 1 | 1.48 | Compared to 2017, an increase in annual suicide rate was found during the pandemic year (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.13–1.14). |

| Chen et al., 2022 [77] | Taiwan | Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare | 2017–2019 | 2020 | 1.11 | 1.03 | Compared to previous years, a decrease in annual suicide rates after the outbreak was found (p = 0.05). |

| de la Torre-Luque et al., 2022 [78] | Spain | National Death Index | 2019 | 2020 | 0.92 | 1.1 | No significant differences in suicide mortality rates between 2019 and 2020 were found (p = 0.18). |

| Faust et al., 2021 [79] | Massachusetts, USA | Massachusetts Department of Health Registry of Vital Records and Statistics | 2015–2019 (2019) * | 2020 | 0.96 | 3.03 | During the pandemic period, the incident rate for suicide deaths in Massachusetts was 0.67 vs. 0.80 per 100,000 person months during the corresponding period in 2019 (IRR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.64–1.00). |

| Gerstner et al., 2022 [80] | Ecuador | National Directorate of Crimes against Life, Violent Deaths, Disappearances, Extortion and Kidnapping (DINASED) | Jan. 2015–Feb. 2020 | Mar. 2020–Jun. 2021 | 0.99 | 1.62 | During the pandemic period, suicide rate was not significantly higher than expected (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92–1.02). |

| Larson et al., 2022 [81] | Michigan, USA | Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) | Jan. 1st, 2006–Mar. 12th, 2020 | Mar. 13th, 2020–Dec. 12th, 2021 | 0.95 | 2.43 | Compared with before, daily suicide incidence rate declined during the pandemic for both females (9.32%; p = 0.01) and males (20.64%; p = 0.04). |

| McIntyre et al., 2021 [13] | Canada | Canadian National Database | Mar. 2010–Feb. 2020 (Mar. 2019–Feb. 2020) * | Mar. 2020–Feb. 2021 | 0.95 | 1.67 | Overall suicide mortality rate decreased from the March 2019–February 2020 period to the March 2020–February 2021 period (absolute difference of 1300 deaths). |

| Mitchel and Li, 2021 [82] | Connecticut, USA | Connecticut Office of the Chief Medical Examiner | Mar. 10th–May 20th for 2014–2019 | Mar. 10th–May 20th for 2020 | 0.96 | 1.64 | The age-adjusted suicide rate was 13% lower than the recent 5-year average during the same period. |

| Page et al., 2022 [83] | Australia | Australian Bureau of Statistics | 2019 | 2020; 2021 | 0.96; 1.11 | 1.25; 0.98 | The suicide rate in 2020 was lower than the 2019 rate, while the decrease was less noteworthy when considering the trend from the beginning of 20th century. |

| Palacio-Mejía et al., 2022 [84] | Mexico | National Epidemiological and Statistical Subsystem of Deaths | 2019 | 2020; 2021 | 0.89; 1.06 | 1.26; 1.26 | The suicide rate for 2019, 2020, and 2021 was 4.7, 5.3, and 5.4 per 100,000 people, respectively. |

| Radeloff et al., 2021 [114] | Leipzig, German | Leipzig Health Authority | 2010–2019 | 2020 | 1.05 | 0.8 | In 2020, suicides rates were lower in periods with severe COVID-19 restrictions (SR = 7.2, χ2 = 4.033, p = 0.045), compared with periods without restrictions (SR = 16.8) |

| Reif-Leonhard et al., 2022 [113] | Frankfurt/Main, German | Institute of Legal Medicine and Communal Health Authority | Mar.–Dec. for 2019 | Mar.–Dec. for 2020 | 0.99 | 1.23 | The number of completed suicides did not change between March–December 2019 and March–December 2020 (IRR = 0.94, p > 0.05). |

| Rogalska and Syrkiewicz-Switała, 2022 [86] | Poland | Ministry of Health | 2017–2019 | 2020 | 1.05 | 0.8 | The total number of annual suicide attacks shows an upward trend from 2017 to 2020. |

| Rück et al., 2020 [87] | Sweden | Statistics Sweden | Jan.–Jun. for 2019 | Jan.–Jun. for 2020 | 1.01 | 1.22 | Suicide rates in January-June 2020 revealed a slight decrease compared to the corresponding rates in January–June 2019 (relative decrease by −1.2% among men and −12.8% among women). |

| Ryu et al., 2022 [91] | South Korea | Statistics Korea’s Microdata Integrated Service | 2017–2019 (2019) * | 2020 | 0.99 | 1.03 | Compared to 2019 (26.9 per 100,000 people), the suicide rate declined in 2020 (25.7). |

| Stene-Larsen et al., 2022 [88] | Norway | Norwegian Cause of Death Registry | 2010– 2019 (2019) * | 2020 | 0.89 | 1.19 | During the pandemic period, the observed suicide rate (12.1 per 100,000 population) was not significantly higher than expected (12.3). |

| Tanaka and Okamoto, 2021 [89] | Japan | Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare | Nov. 2016–Jan. 2020 | Feb.–Jun. for 2020; Jul.–Oct. for 2020 | 1; 0.98 | 1.11; 1.11 | During the first 5 months of the pandemic, monthly suicide rates declined by 14%. |

| Wei et al., 2021 [90] | Suzhou, China | Monitoring System of Death Causes of Suzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention | Jan.–Apr. for 2015–2019 | Jan.–Apr. for 2020 | 1.19 | 0.96 | Suicide was among the top five causes of death, and suicide rate had normal fluctuation during the pandemic. |

| Study Setting | No. of Studies (Samples) | Pooled PR (95% CI; p-Value) | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | tau2 | Q (p-Value) | |||

| Non-clinical settings | 23 (28) | 1.142 (1.018–1.282; p = 0.024) | 97.734% | 0.081 | 1191.667 (0.00) |

| Clinical settings | 18 (23) | 1.134 (1.048–1.227; p = 0.002) | 71.029% | 0.018 | 75.939 (0.00) |

| Moderators | No. of Studies | Point Estimate (95% CI; p-Value) | Total Between | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | df(Q) | p-Value | |||

| Non-clinical samples | |||||

| Population | 31.838 | 3 | 0.000 | ||

| Adolescents | 8 | 1.03 (0.849–1.248; p = 0.296) | |||

| Younger group 1 | 10 | 0.955 (0.803–1.136; p = 0.604) | |||

| General population | 8 | 2.014 (1.604–2.529; p = 0.000) | |||

| Special group 2 | 2 | 0.833 (0.574–1.208; p = 0.335) | |||

| Study design | 9.941 | 1 | 0.002 | ||

| Repeated cross-sectional | 19 | 1.318 (1.132–1.535; p = 0.000) | |||

| Longitudinal | 8 | 0.842 (0.666–1.063; p = 0.148) | |||

| Measurement tool | 0.033 | 1 | 0.857 | ||

| Self-report | 25 | 1.139 (1.012–1.283; p = 0.031) | |||

| Diagnosis | 3 | 1.194 (0.73–1.95; p = 0.48) | |||

| Timeframe for measurement | 0.156 | 1 | 0.693 | ||

| ≤2 weeks | 8 | 1.159 (0.95–1.414; p = 0.146) | |||

| >2 weeks | 19 | 1.217 (1.062–1.394; p = 0.005) | |||

| Data collection | 0.134 | 2 | 0.935 | ||

| Mar–Aug 2020 | 16 | 1.141 (0.964–1.35; p = 0.125) | |||

| Sept 2020–Jan 2021 | 8 | 1.118 (0.895–1.396; p = 0.325) | |||

| Feb. 2021+ | 4 | 1.199 (0.884–1.628; p = 0.243) | |||

| Clinical samples | |||||

| Population | 0.944 | 1 | 0.331 | ||

| Adolescent patients | 15 | 1.171 (1.057–1.297; p = 0.002) | |||

| Adult patients | 8 | 1.081 (0.953–1.225; p = 0.225) | |||

| Measurement tool | 0.259 | 1 | 0.611 | ||

| Self-report | 2 | 1.079 (0.872–1.336; p = 0.484) | |||

| Diagnosis | 21 | 1.146 (1.047–1.255; p = 0.003) | |||

| Timeframe for measurement | 0.067 | 1 | 0.796 | ||

| ≤2 weeks | 20 | 1.129 (1.129–1.027; p = 0.012) | |||

| >2 weeks | 3 | 1.158 (0.976–1.375; p = 0.093) | |||

| Data collection | 0.996 | 1 | 0.318 | ||

| Mar–Aug 2020 | 19 | 1.12 (1.031–1.217; p = 0.007) | |||

| Sept 2020–Feb 2021+ 3 | 4 | 1.292 (0.988–1.688; p = 0.061) | |||

| Study Setting | No. of Studies (Samples) | Pooled PR (95% CI; p-Value) | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | tau2 | Q (p-Value) | |||

| Non-clinical settings | 17 (30) | 1.14 (1.053–1.233; p = 0.001) | 99.996% | 0.036 | 7601.38 (p = 0.000) |

| Clinical settings | 20 (25) | 1.32 (1.17–1.489; p = 0.000) | 70.021% | 0.052 | 80.056 (p = 0.000) |

| Moderators | No. of Studies | Point Estimate (95% CI; p-Value) | Total Between | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | df(Q) | p-Value | |||

| Non-Clinical Samples | |||||

| Population | 4.005 | 2 | 0.135 | ||

| Adolescent | 13 | 1.062 (0.948–1.189; p = 0.3) | |||

| Younger group 1 | 4 | 0.942 (0.673–1.319; p = 0.73) | |||

| General population | 12 | 1.218 (1.089–1.362; p = 0.001) | |||

| Study design | 2.805 | 2 | 0.246 | ||

| Repeated cross-sectional | 12 | 1.245 (1.083–1.43; p = 0.002) | |||

| Longitudinal | 3 | 1.285 (0.817–2.02; p = 0.277) | |||

| Retrospective | 15 | 1.084 (0.983–1.195; p = 0.106) | |||

| Measurement tool | 2.788 | 1 | 0.095 | ||

| Self-report | 15 | 1.248 (1.093–1.425; p = 0.001) | |||

| Diagnosis | 15 | 1.084 (0.983–1.196; p = 0.106) | |||

| Timeframe for measurement | 2.809 | 1 | 0.094 | ||

| ≤2 weeks | 16 | 1.084 (0.983–1.196; p = 0.107) | |||

| >2 weeks | 14 | 1.249 (1.093–1.426; p = 0.001) | |||

| Data collection | 0.397 | 2 | 0.820 | ||

| Mar–Aug 2020 | 15 | 1.15 (1.025–1.289; p = 0.017) | |||

| Sept 2020–Jan 2021 | 7 | 1.174 (0.988–1.395; p = 0.069) | |||

| Feb. 2021+ | 8 | 1.101 (0.966–1.255; p = 0.149) | |||

| Clinical samples | |||||

| Population | 1.044 | 1 | 0.307 | ||

| Adolescent patients | 12 | 1.415 (1.185–1.68; p = 0.000) | |||

| Adult patients | 13 | 1.251 (1.068–1.464; p = 0.005) | |||

| Measurement tool | 0.256 | 1 | 0.613 | ||

| Self-report | 3 | 1.42 (1.036–1.948; p = 0.13) | |||

| Diagnosis | 22 | 1.299 (1.132–1.492; p = 0.000) | |||

| Timeframe for measurement | 0.628 | 1 | 0.428 | ||

| ≤2 weeks | 22 | 1.288 (1.121–1.479; p = 0.000) | |||

| >2 weeks | 3 | 1.158 (0.976–1.375; p = 0.012) | |||

| Data collection | |||||

| Mar–Aug 2020 | 22 | 1.323 (1.164–1.503; p = 0.000) | 0.016 | 1 | 0.901 |

| Sept 2020–Feb 2021+ 2 | 3 | 1.288 (0.685–1.918; p = 0.213) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Y.; Hou, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, N.X. Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043346

Yan Y, Hou J, Li Q, Yu NX. Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043346

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Yifei, Jianhua Hou, Qing Li, and Nancy Xiaonan Yu. 2023. "Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043346

APA StyleYan, Y., Hou, J., Li, Q., & Yu, N. X. (2023). Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043346