Abstract

Background: Taiwan always had low case rates of COVID-19 compared with other countries due to its immediate control and preventive measures. However, the effects of its policies that started on 2020 for otolaryngology patients were unknown; therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the nationwide database to know the impact of COVID-19 preventative measures on the diseases and cases of otolaryngology in 2020. Method: A case-compared, retrospective, cohort database study using the nationwide database was collected from 2018 to 2020. All of the information from outpatients and unexpected inpatients with diagnoses, odds ratios, and correlation matrix was analyzed. Results: The number of outpatients decreased in 2020 compared to in 2018 and 2019. Thyroid disease and lacrimal system disorder increased in 2020 compared to 2019. There was no difference in carcinoma in situ, malignant neoplasm, cranial nerve disease, trauma, fracture, and burn/corrosion/frostbite within three years. There was a highly positive correlation between upper and lower airway infections. Conclusions: COVID-19 preventative measures can change the numbers of otolaryngology cases and the distributions of the disease. Efficient redistribution of medical resources should be developed to ensure a more equitable response for the future.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, an unknown virus broke out in Wuhan, China, which spread globally at a rapid speed [1,2,3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) named this virus COVID-19, which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that is mainly transmitted through respiratory droplets and contact routes between people [1,4]. With Taiwan being geographically in close proximity to China and having a densely urbanized population, it was predicted to be one of the hardest-hit countries. However, as Taiwan immediately took decisive and effective control measures to prevent the spread from the very start of the pandemic, the people of Taiwan are now able to continue their normal lives, with precaution [2,3]. At the end of 2020, the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (CDC) confirmed that, of a total of 799 cases, 704 were imported cases and only 7 people died [5].

Taiwan continues to take control measures for combating the pandemic; the fundamental prevention measures include: prompt border control, social distancing, postponement of large crowd events, and compulsory wearing of surgical masks when outside [2,6,7]. The key principles of the “Taiwan model” are rapid measures, early deployment, prudent actions, and transparency [8,9]. From several previous studies, epidemic prevention strategies can effectively reduce severe respiratory infectious diseases, such as invasive pneumonia disease, tuberculosis, and influenza [10,11]. It also significantly reduced dengue and enterovirus infections [10,12]; however, there were no statistical decreases in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections.

As the pandemic continues, specialists and related staff that deal with significantly increased numbers of hospital patients are at high risk for COVID-19 infection. For specialists that work specifically in close contact with airway management, such as otolaryngology, their examination and treatments are unavoidable for patients. In addition, this has greatly impacted the declining numbers of outpatient visits, delivery of patient care, reduction in waiting time, decrease in identifying new cancer, and significant delays in treatment deliveries [13,14,15]. As COVID-19 hit hard in 2020 for Taiwan, and currently, there is no literature discussing the effects of inpatients and outpatients, or surgeries in otolaryngology with COVID-19 occurrence that had not yet become an epidemic with under surveilled prevention policies. This is the first nationwide study with the aim to disclose the impact of COVID-19 preventative measures on the diseases of otolaryngology. Our hypothesis is that COVID-19 preventative measures can change the numbers of otolaryngology cases and the distributions of the diseases. This study will not only explore the effects of Taiwan’s epidemic prevention measures, but will also add value to future structural hospital procedures, clinical evidence-based decision, and healthcare policy making in knowing how to plan the allocation of medical resources during future possible pandemics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Ethical Consideration

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) was used in this study. This database, which was established in 1995, represents most of the Taiwanese population, if not all, as it contains the data of approximately 23 million residents (over 99%). The NHIRD has often been used by hundreds of published studies [16], providing abundant information related to all aspects of healthcare, from ambulatory and inpatient care to outpatient care and medication data, creating real-world evidence to support healthcare policy-making and clinical decisions. The International Classification of Diseases 9 Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) was used for all the diagnosis codes, and the 10th revision of ICD-10-CM started in 2016. According to the ethical guidelines from the NHIRD, all individual patient material was anonymized before accessing it; therefore, the requirements for informed consent were waived by the Research Ethics Committee. The Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Fu Jen Catholic University was approved (IRB approval number: No. C110199).

2.2. Study Population and Disease Grouping

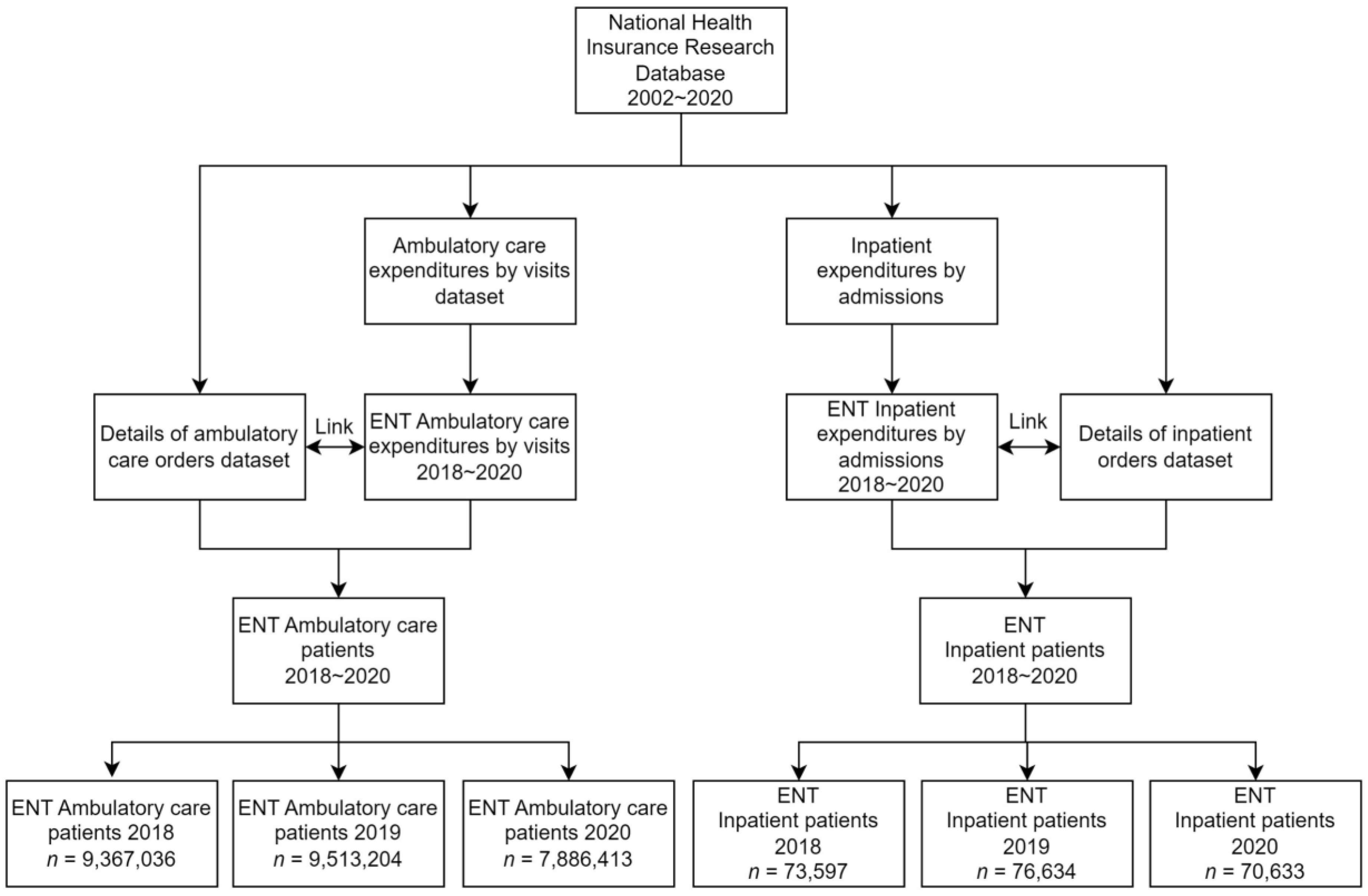

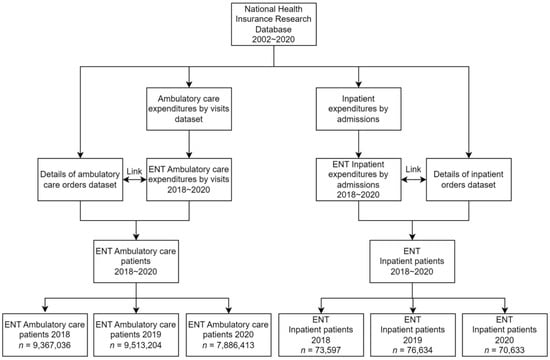

This study was a case-compared, retrospective, cohort database study to detrmine the before and after effects of COVID-19 prevention measures on infectious and non-infectious diseases. The database search included otolaryngology inpatients and outpatient data from 2018 to 2020, collecting all the different diagnoses and categories of surgical procedures, and the number of visits, as seen in Figure 1. The inpatient and outpatient operations are included according to the operation codes in the National Health Insurance Payment Standard. The total inpatient and outpatient cases are identified in Table 1 and Table 2. All operations that were performed by otolaryngologists from 2018 to 2020 were included in this study, and were then divided into inpatient groups and outpatient groups, according to whether the patients were hospitalized. All groupings of the diagnoses of the outpatients in the otolaryngology department are in Appendix A, Table A1. An additional analysis of unexpected inpatient diagnoses in the otolaryngology department was performed. All patient characteristics were available from the database.

Figure 1.

Research flow diagram of the database from the National Health Insurance Research Database.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of inpatient otolaryngology cases in 2018 to 2020.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of outpatient otolaryngology cases in 2018 to 2020.

2.3. Statistics

All statistical analyses were analyzed using the R programming software (R software, version 4.0.3, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the counts and percentages of the outcome variables. The Chi-square test was used to test the relevance of age, gender, region, and salary level. An odds ratio was used to calculate the change in the ratio of inpatient and outpatient diagnoses each year in order to calculate the correlation strength. The year 2019 was used as the benchmark for analysis. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to calculate the correlation between each diagnosis. Additional growth rate and trend check Poisson regression calculations were analyzed and are shown in Table A3 and Table A4 of Appendix A. The growth rates were formulated by subtracting the initial month and the end month and then dividing that by the initial month (for example, where January is the initial month and February is the end month). The unit of growth rate is a percentage. Poisson regression was used when the trend direction was consistent Therefore, the p-value was blank if it was not analyzed. The difference was considered significant if the two-sided p-value was ≤0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 and Table 2 display the baseline characteristics of gender, age group, area, and monthly salary from 2018 to 2020 for inpatient and outpatient otolaryngology cases. There were more outpatient cases than inpatient cases throughout all three years, with 2018 having 9,367,036 compared to 73,597, 2019 having 9,513,204 compared to 76,634, and 2020 having 7,886,413 outpatient cases compared to 70,633 inpatient cases. There were significant differences in age group, area, and monthly salary for both inpatient and outpatient otolaryngology cases. Only outpatient otolaryngology cases displayed additional significant differences for gender.

Table 3 and Table 4 show the total numbers of outpatients and unexpected inpatients along with their odds ratios from 2018 to 2020. Thyroid disease and lacrimal system disorder persistently increased from 2018 to 2020 in the outpatient diagnoses groups. The groups that had no significant changes from 2019 to 2020 were malignant neoplasm, trauma and fracture, cranial nerve disease, carcinoma in situ, and burn/corrosion/frostbite. The groups that had a significant decrease from 2019 to 2020 were lower and upper airway infection, voice and speech disorder, chronic lower airway disorder, otitis media, acute gastroenteritis, and chronic rhino sinusitis. There were no unexpected inpatient diagnosis groups that had persistent increases from 2018 to 2020.

Table 3.

Total numbers of outpatients and odds ratios in each diagnosis group from 2018 to 2020.

Table 4.

Total numbers of unexpected inpatient diagnoses and odds ratios in each diagnosis group from 2018 to 2020.

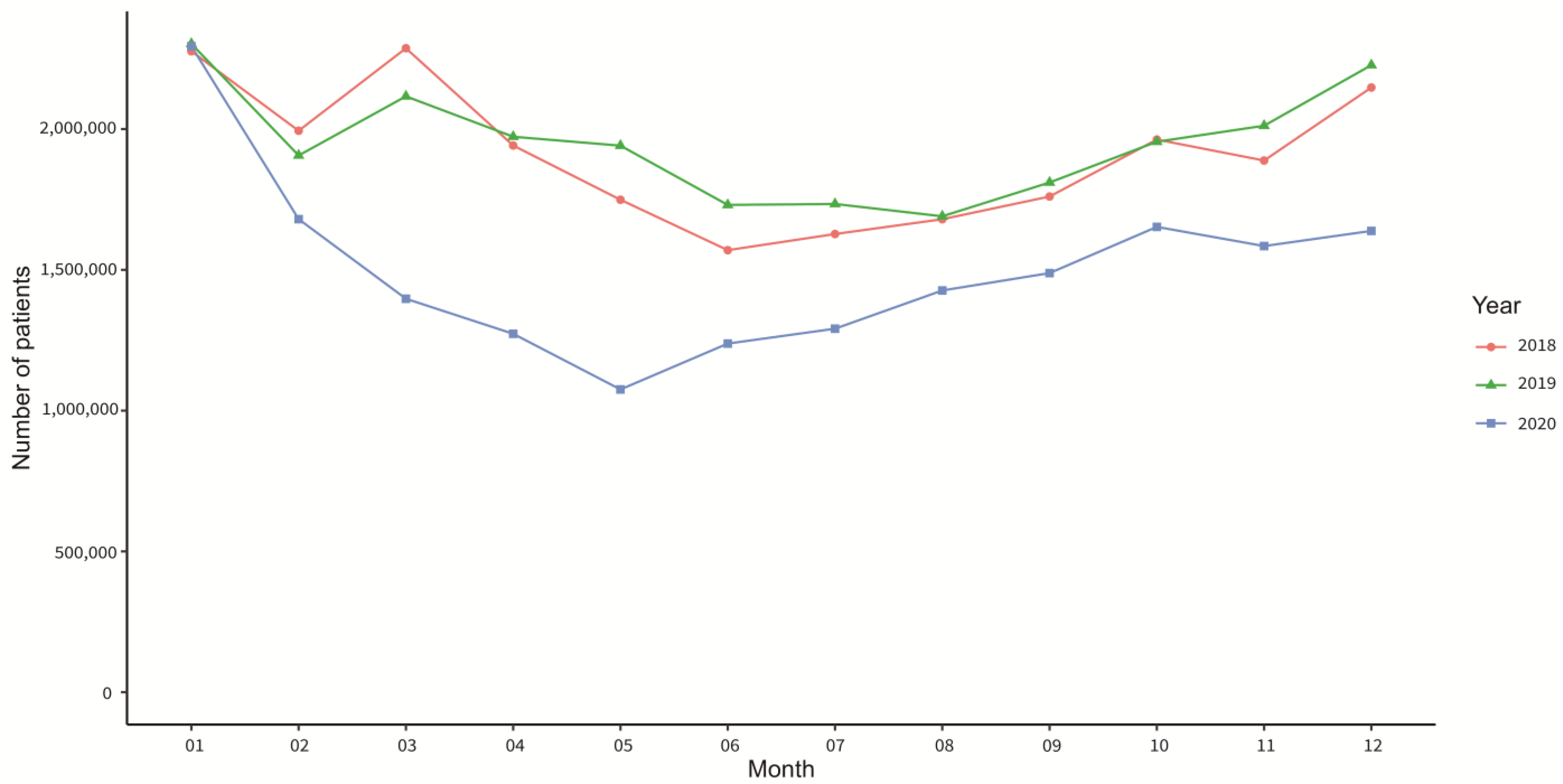

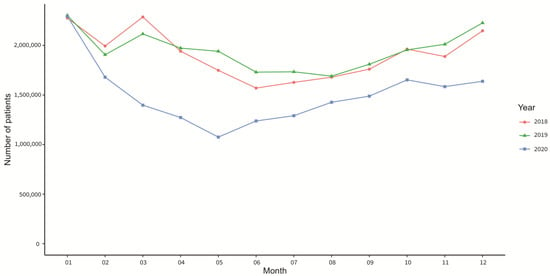

Figure 2 displays the monthly number of outpatients from 2018 to 2020. There was a major decreasing number of cases from January 2020 to May 2020, until it slowly increased from June 2020 to December 2020.

Figure 2.

Total number of otolaryngology outpatients in each month from 2018 to 2020.

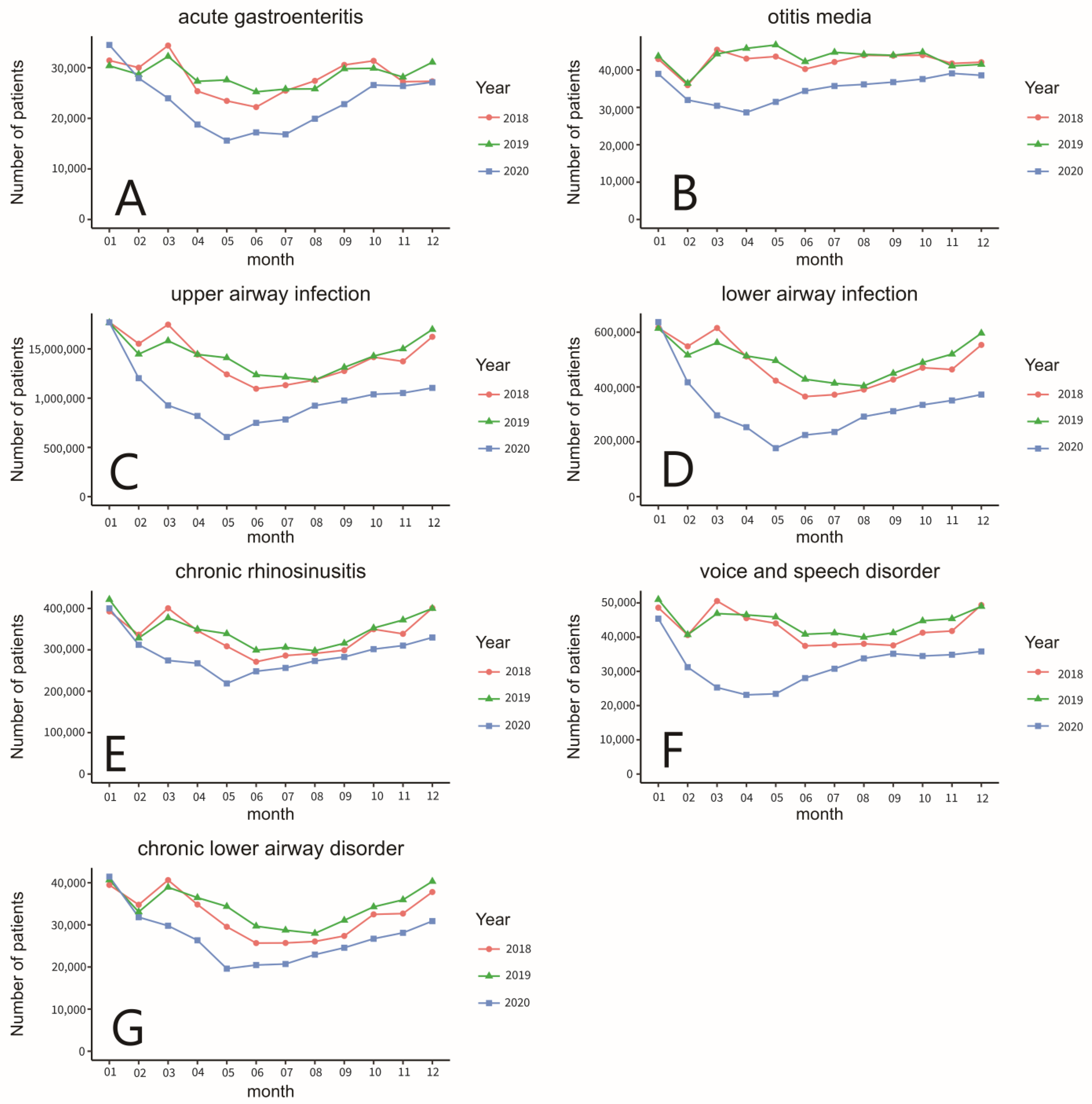

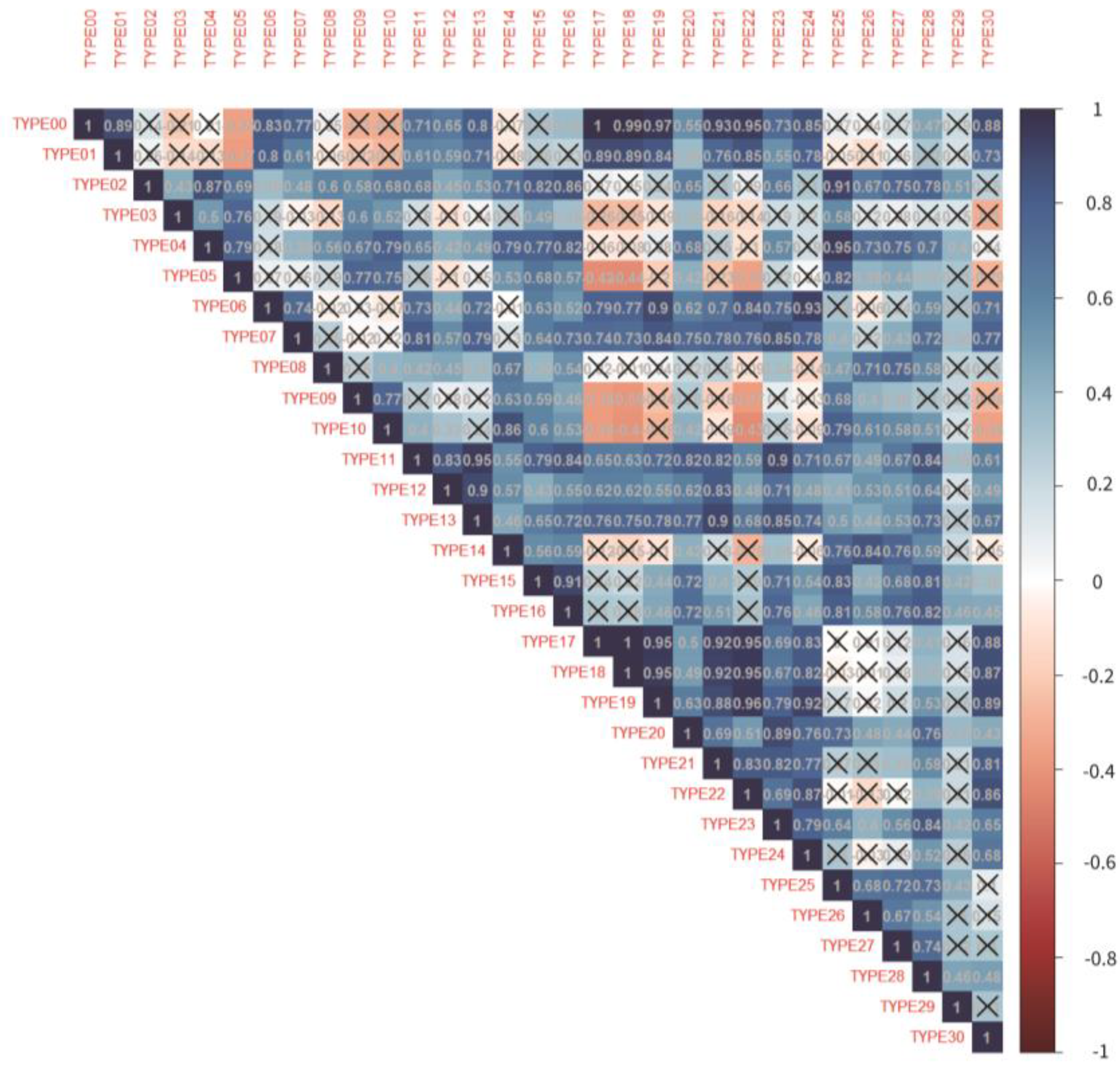

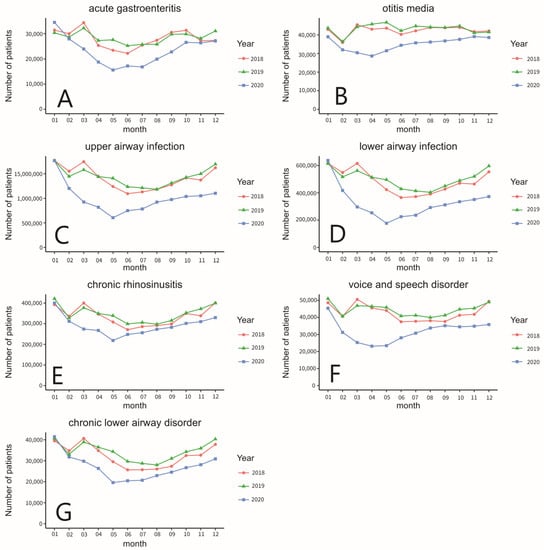

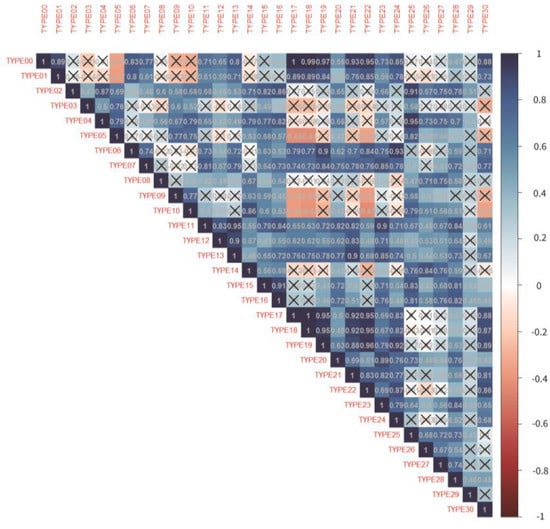

Figure 3 shows the monthly number of patients from the top seven outpatient diagnoses groups that had a decrease from 2019 to 2020. Growth rate and trend check of each monthly comparison throughout all three years of the outpatient diagnoses group are shown in Table A3 in Appendix A. Figure 4 shows the correlation matrix between each outpatient diagnosis group. The type code numbers are according to the diagnosis grouping in Appendix A, Table A2.

Figure 3.

(A) The total number of outpatients of acute gastroenteritis, (B) otitis media, (C) upper airway infection, (D) lower airway infection, (E) chronic rhinosinusitis, (F) voice and speech disorder, and (G) chronic lower airway disorder from 2018 to 2020.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix between the diagnoses grouping. (“X” in the correlation matrix represents p > 0.05).

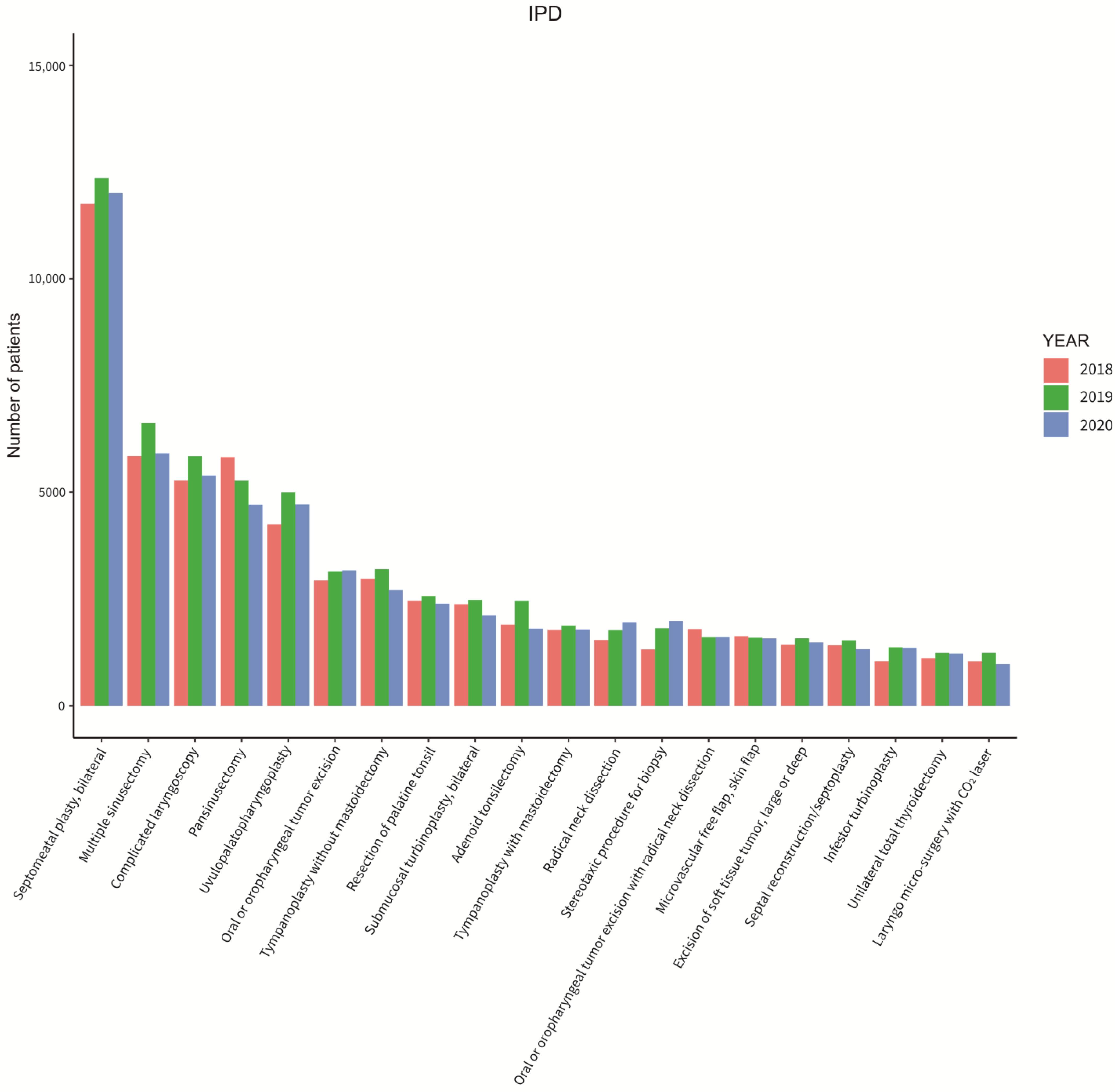

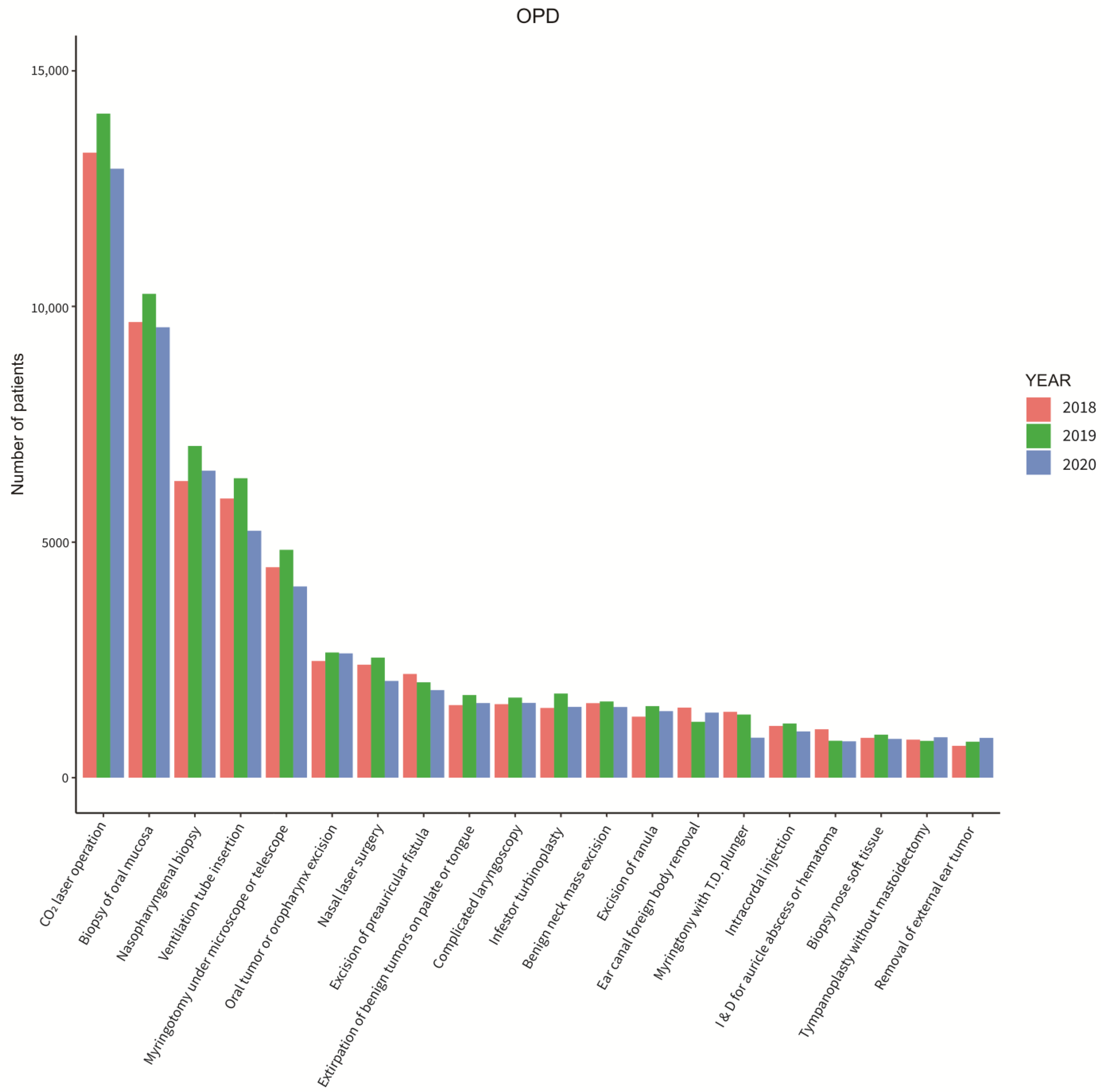

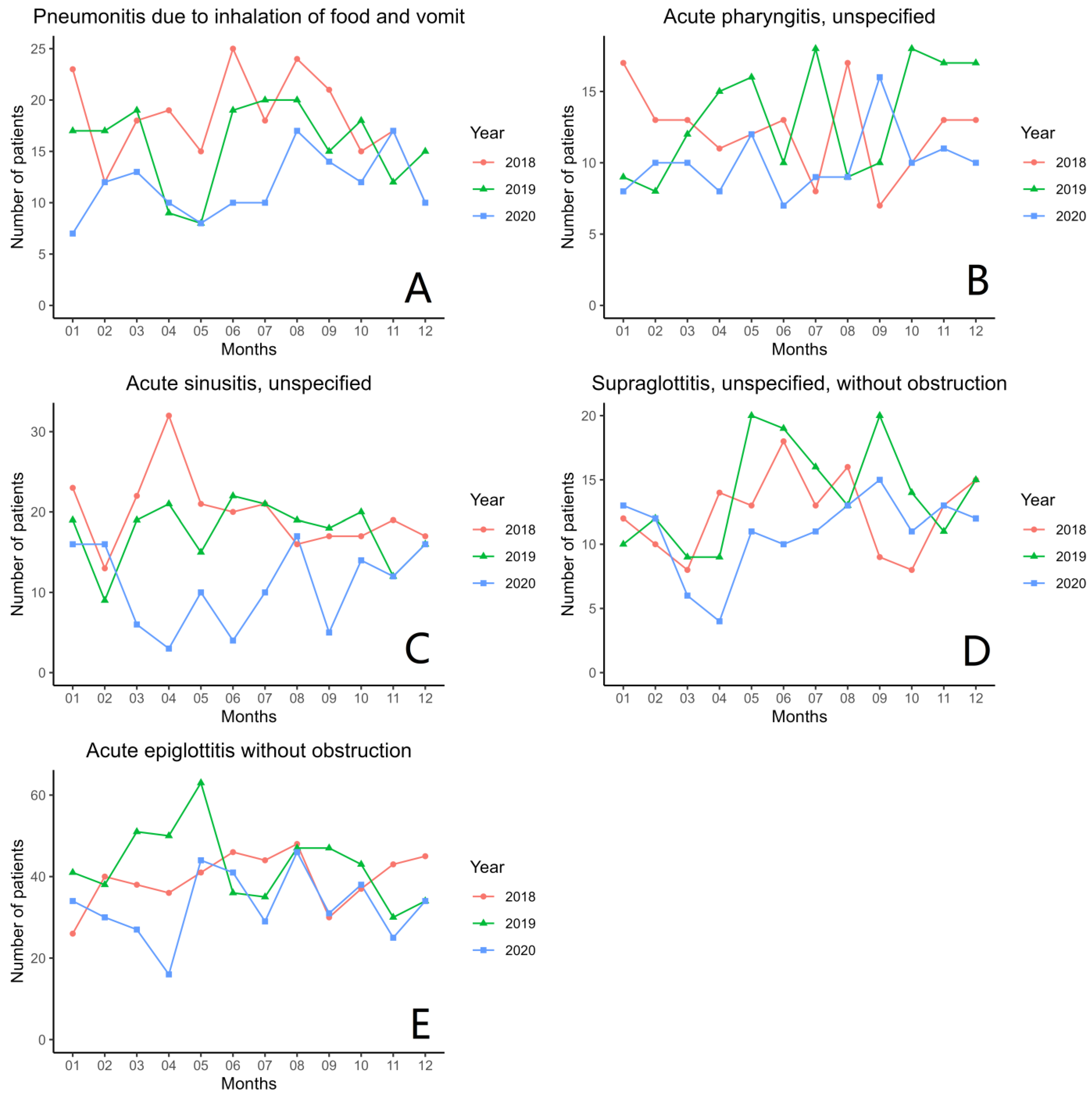

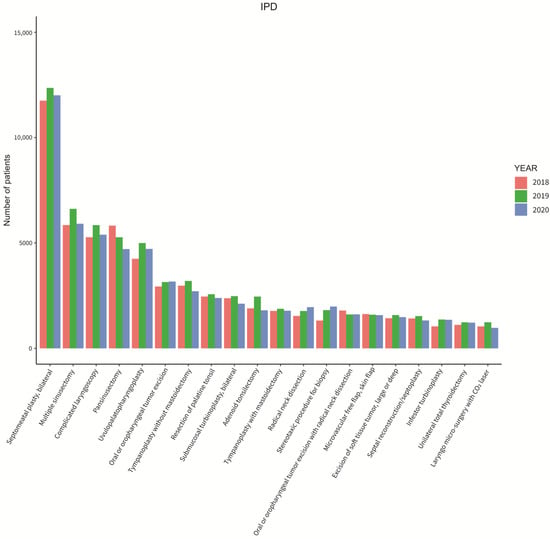

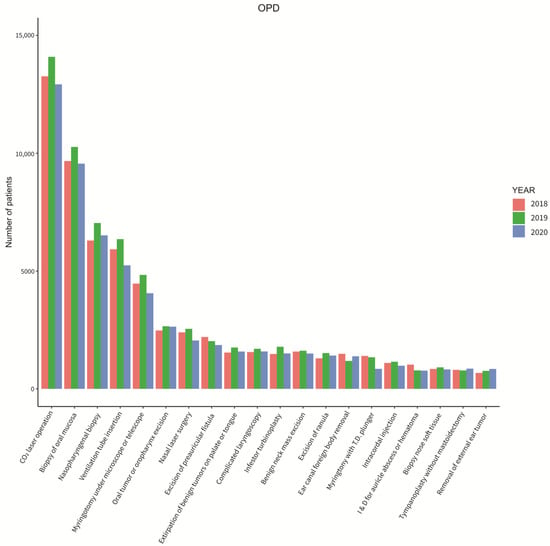

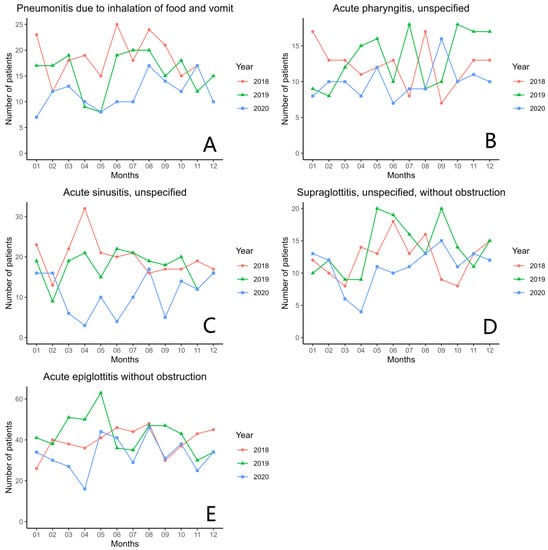

Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the different types of surgeries that were operated on from 2018 to 2020 by inpatients and outpatients. The most common surgeries that were performed were bilateral septomeatal plasty in inpatient cases and CO2 laser operation in outpatient cases throughout all three years. Coming in second was the biopsy of oral mucosa for outpatients throughout all three years. Lastly, Figure 7 displays the six most common unexpected inpatient diagnoses throughout each month from 2018 to 2020. An additional growth rate and trend check of each monthly comparison throughout all three years of the unexpected inpatient diagnoses are shown in Table A4 of Appendix A.

Figure 5.

Total otolaryngology surgeries performed on inpatients in 2018 to 2020.

Figure 6.

Total otolaryngology surgeries performed on outpatients in 2018 to 2020.

Figure 7.

The total number of unexpected inpatient diagnoses of (A) pneumonitis, (B) acute pharyngitis, (C) acute sinusitis, (D) supraglottitis, and (E) acute epiglottitis from 2018 to 2020.

4. Discussion

It is unclear what the effect on Taiwan would have been if it had undergone a significant COVID-19 outbreak with under-surveilled prevention policies, as Taiwan had immediate control measures for combating the pandemic. As there was no current literature discussing this issue in the last few years, to our knowledge, this study is the first to use the national real-world database to analyze and disclose the impact of COVID-19 and Taiwan’s epidemic prevention policy on otolaryngology patients and surgeries.

In this study, the number of outpatient visits in 2018 and 2019 is relatively similar in each month. From December to March, the number of visits is higher, and from June to August, it is lower overall. The most common diseases that are seen in otolaryngology clinics are upper airway infection, lower airway infection, and chronic rhinosinusitis, according to Table 3. The peak season for these diseases is usually in the winter, where there is a significant decrease in temperature, while in the summer from June to August, there is a significant increase in temperature and a decrease in patient visits. However, in 2020, the numbers from this study are different than in 2018 and 2019. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in January 2020, Taiwan immediately implemented a mask-wearing regulation in February 2020, vigorously advocated social distancing, and executed stringent border control [6]. Due to these measures, the number of patient visits to the otolaryngology clinics significantly decreased from February until May, there was a slow increase back to typical levels from 2018 and 2019, as shown in Figure 2. Possibly, unnecessary fear and panic may have been present at the beginning of the pandemic among patients seeking medical treatment. In addition, the government’s and CDC’s recommendation to not go to the hospital unless necessary could be another factor for the decrease in numbers. From June to October 2020, the numbers returned to similar levels as two years ago, but the overall number is still significantly smaller. In December, the peak of hospital visits and the number of patients can be seen to decrease significantly. This could be explained by the effective epidemic prevention advocated by the government and the CDC, which has not only reduced the rapid spread of COVID-19, but also greatly reduced the common respiratory diseases seen in hospital visits.

Previous literature has discussed that the willingness of outpatients to see a doctor greatly decreased due to COVID-19. In Table 3, most of the diagnosis groups can be seen to decrease from 2019 to 2020; however, some diagnoses groups did not show a change in continuing to seek medical treatment. Groups such as thyroid disease, malignant neoplasm of the head and neck, in situ carcinoma, cranial nerve disease, and burn/corrosion/frostbite of the head, face, and neck require long-term follow-up with long-term drug prescriptions. At that time, patients may have maintained regular hospital visits and would not hesitate to seek medical treatment, due to possible serious effects if help was not sought.

From Figure 2, this study saw many significant reductions in outpatient visits in 2020. There were obvious differences in lower airway infection, upper airway infection, voice and speech disorder, chronic lower airway disorder, otitis media, acute gastroenteritis, and chronic rhino sinusitis. By examining further each month from 2018 to 2020, in Figure 3, it can be found that upper and lower airway infection and voice and speech disorders, which originally had seasonal differences, showed a gradual, but noticeable, increase in the second half of 2020, in comparison with chronic rhino sinusitis and lower airway disorder. While the overall outpatient visits were declining, the seasonal increase remains similar in 2020 to that of 2018 and 2019. This observation shows that the Taiwan epidemic prevention policy that came effective immediately had a strong influence on acute respiratory infection symptoms, but also, significantly reduced chronic upper and lower airway disorders.

Additional correlation statistics between all outpatient diagnoses groupings were analyzed and it was found the upper and lower airway infections had a completely positive correlation. This indicated that these two types of diseases tend to occur in the same season with the same transmission route, showing the same change trend under the epidemic situation. Similar discussions were also examined from a 2018 clinical study, examining the correlation between upper and lower airway inflammations, suggesting that the inflammatory process may be the most essential link in the cross-talk between the upper and lower airways [17]. There were also positive correlations between upper and lower airway infections, chronic rhino sinusitis, voice and speech disorders, acute gastroenteritis, and chronic lower airway disorders. This indicated that these diseases were more likely to appear together simultaneously and have a tendency to increase and decrease at the same time. Lastly, the unusual correlation was the negative correlation between thyroid disease, lacrimal system disorders, and otitis externa with chronic lower airway disorders, upper airway infections, and lower airway infections. This may be explained by the possible fear of patients not wanting to go to the hospitals for respiratory-related treatments during the epidemic. However, for diseases such as thyroid, lacrimal system disorders, and otitis externa, which are less likely to cause droplet infections, there are still related medical needs, and therefore, there may be a tendency to diverge.

Figure 5 and Figure 6 did not indicate additional information from the number of patients according to the different surgical procedures that were performed. Throughout all three years, there were no differences, which may indicate that under the prevention measure controls, Taiwan’s medical resources are still sufficient with the public to continue to be confident in the medical treatment provided.

From 2019 to 2020, the top five unexpected inpatient diagnoses that were evaluated remained the same, including abscess and cellulitis of the face and neck, sialoadenitis, vertigo, sudden hearing loss, and Bell’s palsy. These diagnoses did not affect the patients who needed to be hospitalized to receive active treatment, nor will they reduce the incidence of the disease.

Since the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, the increase of previous studies has clearly shown that COVID-19 itself and many related drugs and vaccines have some side effects, many of which are related to otolaryngology [18,19]. Common otolaryngology symptoms of COVID-19 patients may include tinnitus, gingivitis, sudden hearing loss, Bell’s palsy, and hoarseness [20]. In addition, the side effects of drug and COVID-19 vaccine usage include systemic event reactions, injection site adverse reactions, and serious vaccine-related adverse events. Their data also show to have symptoms such as dizziness, hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus, cough, rhinorrhea, throat irritation, pharyngalgia, nasal congestion, blurry vision with dizziness, and dysgeusia [21,22,23]. However, this study is mainly focused on Taiwan’s population, which has not yet experienced a pandemic in 2020, when the total number of confirmed cases was only 799 [5]. Relevant drugs and vaccines have not come out nor are widely used in Taiwan, so the related side effects had no effect, as shown by the results of this study.

This study had the advantage of using a national population dataset algorithm that included a large-scale sample size. This study allows people to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Taiwan’s epidemic prevention policy on otolaryngology outpatients and unexpected inpatient hospitalizations. By analyzing all the diseases and surgeries that occurred from 2018 to 2020, this study also evaluated the further changes in different months with a complete correlation of the outpatient diagnoses.

The limitations for this study were, firstly, that it did not include an experimental comparison. It was unclear whether the epidemic panic from the patients or the epidemic prevention measures can have a significant impact on the related diseases. Future design studies are worth investigating in providing stronger evidence of the post-epidemic era so that government and healthcare policymakers can have more references for formulating regulations and allocating medical resources. Secondly, because Taiwan did not declare a pandemic in 2020, and as telemedicine was not commonly used, it was impossible to know whether the preventive measures will also have an impact on these patients and the types of diseases. Lastly, this study focused on the analysis of otolaryngology patients. If possible, future studies should analyze whether the preventative measures in Taiwan have the same impact on other departments.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 preventative measures can change the numbers of otolaryngology cases and the distributions of the diseases. Therefore, if a global pandemic will happen again in the future, we hope that complete effective measures and policies for epidemic prevention can maintain the maintain the medical capacity and reduce common infectious respiratory diseases. At the same time, medical institutions should put more medical resources and time into providing regular follow-up, long-term drug treatments, and cancer management, as well as routinely supply the treatment of emergency traumatic illnesses, to ensure a more equitable response for the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-Y.C. and C.-H.H.; methodology, H.-Y.C., C.-H.H. and Y.-W.K.; software, Y.-W.K.; validation, H.-Y.C., C.-H.H., B.-C.S. and M.C.; formal analysis, Y.-W.K. and B.-C.S.; investigation, H.-Y.C., C.-H.H. and B.-C.S.; resources, M.C.; data curation, H.-Y.C., Y.-W.K. and B.-C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-Y.C. and C.-H.H.; writing—review and editing, H.-Y.C., C.-H.H., B.-C.S. and M.C.; visualization, H.-Y.C. and Y.-W.K.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, M.C.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fu Jen Catholic University (A0111183) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST109-2221-E030-011-MY3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Fu Jen Catholic University Hospital (IRB approval number: No. C110199). Consent form was not applicable in this study. All data collected in this study were encrypted using the same encryption algorithm to cross-link the data while protecting the privacy of the patients.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

These data were available to us as staffs of the Department of Otolaryngology at Fu Jen Catholic University Hospital and at Fu Jen Catholic University, using the National Hospital Research Database (NHIRD). These data are protected by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and patient privacy laws in Taiwan. No public links of the NHIRD are available; however, they will be made available after the appropriate data privacy and human subject approvals needed by the institution. Requests and questions should be sent to 081438@mail.fju.edu.tw.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

ICD-10-CM codes of diagnoses of the outpatients in the otolaryngology department.

Table A1.

ICD-10-CM codes of diagnoses of the outpatients in the otolaryngology department.

| Diagnosis | ICD Code |

|---|---|

| 1. Acute Gastroenteritis | ICD-10-CM: A04, A05, A08, A09 |

| 2. Malignant neoplasm of head and neck | ICD-10-CM: C00-14, C30-32, C43, C49.0, C72.2, C72.4, C76.0, C81-86 |

| 3. Carcinoma in situ | ICD-10-CM: D00, D02, D03 |

| 4. Benign neoplasm | ICD-10-CM: D10-11, D14, D17-18, D21, D23, D37-38 |

| 5. Thyroid disease | ICD-10-CM: C73, D34, D44.0, E04-06 |

| 6. Headache | ICD-10-CM: G43-44, R51 |

| 7. Sleep disorder | ICD-10-CM: F51, G47 |

| 8. Cranial nerve disease | ICD-10-CM: G50-52 |

| 9. Lacrimal system disorder | ICD-10-CM: H04 |

| 10. Otitis externa | ICD-10-CM: H60.0-60.3, H60.5-60.6, H60.8-60.9 |

| 11. Other disease of external ear | ICD-10-CM: H60.4, H61.0-61.3, H61.8-61.9 |

| 12. Otitis media | ICD-10-CM: H65.0-65.4, H66, H92, H70 |

| 13. Eustachian tube disorder | ICD-10-CM: H68-69 |

| 14. Other disease of middle ear | ICD-10-CM: H71-74, H80 |

| 15. Vertigo | ICD-10-CM: H81-83, R42 |

| 16. Hearing loss and tinnitus | ICD-10-CM: H90-91, H93 |

| 17. Upper airway infection | ICD-10-CM: B27, B30.2, J00-06, J09-11, J36, J39, R05-07, R50 |

| 18. Lower airway infection | ICD-10-CM: J12-16, J18, J20-22 |

| 19. Chronic rhino sinusitis | ICD-10-CM: J30-34, R09.81-09.82 |

| 20. Chronic laryngopharyngeal disorder | ICD-10-CM: J35, J37, R13 |

| 21. Voice and speech disorder | ICD-10-CM: F80, J38, R47, R49 |

| 22. Chronic lower airway disorder | ICD-10-CM: J40, J42-45, J47 |

| 23. Oral cavity and salivary gland disorder | ICD-10-CM: B37.0, B37.83, K05, K09, K11-14 |

| 24. Gastroesophageal inflammation and ulcer | ICD-10-CM: K20-21, K25-29 |

| 25. Skin/subcutaneous tissue/lymphatic disorder | ICD-10-CM: B00, B02, B07, L02-04, L20, L72, R22, R59 |

| 26. Congenital deformity | ICD-10-CM: Q16-18, Q30-32, Q35-38 |

| 27. Trauma and fracture of head, face and neck | ICD-10-CM: S00.3-00.5, S00.8-00.9, S01.2-01.5, S01.8-01.9, S02-03, S04.5-04.6, S08.1, S08.8, S09.2-09.3, S09.9, S10, S11.01, S11.03, S11.1-11.2, S11.8-11.9, S17, S19 |

| 28. Foreign body of head and neck | ICD-10-CM: T16, T17.0-17.3, T18.0 |

| 29. Burn/corrosion/frostbite of head, face and neck | ICD-10-CM: T20, T27, T28.0, T28.41, T28.5, T28.91, T33.0-33.1, T34.0-34.1, T49.6 |

| 30. Other unspecified disease | ICD-10-CM: M26.6, M35.0, R04, R43, Z01.1, Z96.2 |

Table A2.

Diseases according to the type code.

Table A2.

Diseases according to the type code.

| Type Code | Diseases |

|---|---|

| TYPE01 | Acute gastroenteritis |

| TYPE02 | Malignant neoplasm of head and neck |

| TYPE03 | Carcinoma in situ |

| TYPE04 | Benign neoplasm |

| TYPE05 | Thyroid disease |

| TYPE06 | Headache |

| TYPE07 | Sleep disorder |

| TYPE08 | Cranial nerve disease |

| TYPE09 | Lacrimal system disorder |

| TYPE10 | Otitis externa |

| TYPE11 | Other disease of external ear |

| TYPE12 | Otitis media |

| TYPE13 | Eustachian tube disorder |

| TYPE14 | Other disease of middle ear |

| TYPE15 | Vertigo |

| TYPE16 | Hearing loss and tinnitus |

| TYPE17 | Upper airway infection |

| TYPE18 | Lower airway infection |

| TYPE19 | Chronic rhinosinusitis |

| TYPE20 | Headache |

| TYPE21 | Voice and speech disorder |

| TYPE22 | Chronic lower airway disorder |

| TYPE23 | Oral cavity and salivary gland disorder |

| TYPE24 | Gastroesophageal inflammation and ulcer |

| TYPE25 | Skin/subcutaneous tissue/lymphatic disorder |

| TYPE26 | Congenital deformity |

| TYPE27 | Trauma and fracture of head, face and neck |

| TYPE28 | Foreign body of head and neck |

| TYPE29 | Burn/corrosion/frostbite of head, face and neck |

| TYPE30 | Other unspecified disease |

Table A3.

Outpatient diagnoses monthly growth rate comparison.

Table A3.

Outpatient diagnoses monthly growth rate comparison.

|

Outpatient Diagnoses Grouping/ Monthly Comparison |

2018 Growth Rate (%) |

2019 Growth Rate (%) |

2020 Growth Rate (%) | 2018 vs. 2019 | 2019 vs. 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute gastroenteritis | |||||

| January to February | −4.5 | −5.6 | −19.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| February to March | 14.6 | 12.4 | −14.2 | <0.001 | |

| March to April | −26.2 | −15.3 | −21.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| April to May | −7.5 | 1.0 | −16.9 | ||

| May to June | −5.2 | −8.5 | 10.3 | <0.001 | |

| June to July | 14.6 | 2.2 | −2.2 | <0.001 | |

| July to August | 7.6 | 0.1 | 18.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| August to September | 11.5 | 15.4 | 14.5 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| September to October | 2.6 | 0.3 | 16.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| October to November | −13.1 | −5.8 | −0.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| November to December | 0.3 | 10.4 | 2.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Otitis media | |||||

| January to February | −16.3 | −16.7 | −18.0 | 0.163 | <0.001 |

| February to March | 26.4 | 21.6 | −4.8 | <0.001 | |

| March to April | −5.3 | 3.4 | −5.8 | ||

| April to May | 1.3 | 2.0 | 9.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| May to June | −7.7 | −9.6 | 9.3 | <0.001 | |

| June to July | 4.7 | 5.9 | 3.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| July to August | 4.3 | −1.2 | 1.2 | ||

| August to September | −0.3 | −0.5 | 1.7 | <0.001 | |

| September to October | 0.4 | 1.9 | 2.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| October to November | −5.1 | −8.2 | 4.0 | <0.001 | |

| November to December | 0.8 | 1.0 | −1.3 | <0.001 | |

| Upper airway infection | |||||

| January to February | −12.4 | −18.0 | −32.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| February to March | 12.5 | 9.3 | −22.9 | <0.001 | |

| March to April | −17.4 | −8.7 | −11.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| April to May | −13.9 | −2.3 | −26.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| May to June | −11.8 | −12.3 | 23.7 | <0.001 | |

| June to July | 3.3 | −1.8 | 4.6 | ||

| July to August | 4.7 | −2.4 | 17.9 | ||

| August to September | 7.6 | 10.8 | 5.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| September to October | 11.0 | 8.7 | 6.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| October to November | −3.0 | 5.2 | 1.3 | <0.001 | |

| November to December | 18.2 | 13.1 | 4.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Lower airway infection | |||||

| January to February | −11.0 | −15.9 | −34.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| February to March | 12.2 | 8.8 | −28.9 | <0.001 | |

| March to April | −16.9 | −8.6 | −14.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| April to May | −17.2 | −3.4 | −30.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| May to June | −13.7 | −13.7 | 27.2 | 0.728 | |

| June to July | 1.9 | −3.4 | 4.9 | ||

| July to August | 5.0 | −2.4 | 23.8 | ||

| August to September | 9.4 | 11.4 | 6.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| September to October | 10.1 | 8.8 | 7.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| October to November | −1.3 | 6.3 | 4.8 | <0.001 | |

| November to December | 19.3 | 14.7 | 6.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | |||||

| January to February | −14.3 | −22.1 | −22.0 | <0.001 | 0.474 |

| February to March | 19.0 | 14.9 | −12.1 | <0.001 | |

| March to April | −13.5 | −7.3 | −2.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| April to May | −10.9 | −3.1 | −18.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| May to June | −12.1 | −11.8 | 13.4 | <0.001 | |

| June to July | 5.5 | 2.3 | 3.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| July to August | 1.8 | −2.7 | 6.5 | ||

| August to September | 2.7 | 6.0 | 3.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| September to October | 16.9 | 11.7 | 6.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| October to November | −3.2 | 5.5 | 2.8 | <0.001 | |

| November to December | 18.4 | 7.5 | 6.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Voice and speech disorder | |||||

| January to February | −16.5 | −20.2 | −31.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| February to March | 24.5 | 15.1 | −19.0 | <0.001 | |

| March to April | −9.9 | −0.8 | −8.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| April to May | −3.4 | −1.3 | 1.3 | <0.001 | |

| May to June | −14.9 | −11.0 | 19.6 | <0.001 | |

| June to July | 0.8 | 0.9 | 9.7 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| July to August | 0.9 | −3.0 | 9.8 | ||

| August to September | −1.2 | 3.2 | 4.0 | <0.001 | |

| September to October | 9.9 | 8.5 | −1.9 | <0.001 | |

| October to November | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.023 | <0.001 |

| November to December | 18.1 | 7.9 | 2.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic lower airway disorder | |||||

| January to February | −11.9 | −18.7 | −23.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| February to March | 16.8 | 17.7 | −6.4 | 0.008 | |

| March to April | −14.3 | −6.3 | −11.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| April to May | −15.2 | −5.7 | −25.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| May to June | −13.1 | −13.6 | 4.4 | 0.072 | |

| June to July | 0.1 | −3.2 | 1.2 | ||

| July to August | 1.4 | −2.6 | 10.8 | ||

| August to September | 5.0 | 11.1 | 7.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| September to October | 18.7 | 10.3 | 8.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| October to November | 0.6 | 4.9 | 5.3 | <0.001 | 0.028 |

| November to December | 15.7 | 12.2 | 9.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Table A4.

Unexpected inpatient diagnoses monthly growth rate comparison.

Table A4.

Unexpected inpatient diagnoses monthly growth rate comparison.

|

Unexpected Inpatient Diagnoses/ Monthly Comparison |

2018 Growth Rate (%) |

2019 Growth Rate (%) |

2020 Growth Rate (%) | 2018 vs. 2019 | 2019 vs. 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonitis due to inhalation of food and vomit | |||||

| January to February | −47.8 | 0.0 | 71.4 | ||

| February to March | 50.0 | 11.8 | 8.3 | 0.054 | 0.777 |

| March to April | 5.6 | −52.6 | −23.1 | 0.198 | |

| April to May | −21.1 | −11.1 | −20.0 | 0.561 | 0.626 |

| May to June | 66.7 | 137.5 | 25.0 | 0.09 | 0.013 |

| June to July | −28.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 | ||

| July to August | 33.3 | 0.0 | 70.0 | ||

| August to September | −12.5 | −25.0 | −17.6 | 0.333 | 0.632 |

| September to October | −28.6 | 20.0 | −14.3 | ||

| October to November | 13.3 | −33.3 | 41.7 | ||

| November to December | −41.2 | 25.0 | −41.2 | ||

| Acute pharyngitis, unspecified | |||||

| January to February | −23.5 | −11.1 | 25.0 | 0.492 | |

| February to March | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | ||

| March to April | −15.4 | 25.0 | −20.0 | ||

| April to May | 9.1 | 6.7 | 50.0 | 0.826 | 0.034 |

| May to June | 8.3 | −37.5 | −41.7 | 0.862 | |

| June to July | −38.5 | 80.0 | 28.6 | 0.174 | |

| July to August | 112.5 | −50.0 | 0.0 | ||

| August to September | −58.8 | 11.1 | 77.8 | 0.034 | |

| September to October | 42.9 | 80.0 | −37.5 | 0.349 | |

| October to November | 30.0 | −5.6 | 10.0 | ||

| November to December | 0.0 | 0.0 | −9.1 | ||

| Acute sinusitis, unspecified | |||||

| January to February | −43.5 | −52.6 | 0.0 | 0.669 | |

| February to March | 69.2 | 111.1 | −62.5 | 0.299 | |

| March to April | 45.5 | 10.5 | −50.0 | 0.039 | |

| April to May | −34.4 | −28.6 | 233.3 | 0.715 | |

| May to June | −4.8 | 46.7 | −60.0 | ||

| June to July | 5.0 | −4.5 | 150.0 | ||

| July to August | −23.8 | −9.5 | 70.0 | 0.257 | |

| August to September | 6.3 | −5.3 | −70.6 | 0.001 | |

| September to October | 0.0 | 11.1 | 180.0 | <0.001 | |

| October to November | 11.8 | −40.0 | −14.3 | 0.174 | |

| November to December | −10.5 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 1 | |

| Supraglottitis, unspecified, without obstruction | |||||

| January to February | −16.7 | 20.0 | −7.7 | ||

| February to March | −20.0 | −25.0 | −50.0 | 0.806 | 0.317 |

| March to April | 75.0 | 0.0 | −33.3 | 0.009 | 0.083 |

| April to May | −7.1 | 122.2 | 175.0 | 0.455 | |

| May to June | 38.5 | −5.0 | −9.1 | 0.668 | |

| June to July | −27.8 | −15.8 | 10.0 | 0.433 | |

| July to August | 23.1 | −18.8 | 18.2 | ||

| August to September | −43.8 | 53.8 | 15.4 | 0.096 | |

| September to October | −11.1 | −30.0 | −26.7 | 0.338 | 0.855 |

| October to November | 62.5 | −21.4 | 18.2 | ||

| November to December | 15.4 | 36.4 | −7.7 | 0.306 | |

| Acute epiglottitis without obstruction | |||||

| January to February | 53.8 | −7.3 | −11.8 | 0.53 | |

| February to March | −5.0 | 34.2 | −10.0 | ||

| March to April | −5.3 | −2.0 | −40.7 | 0.401 | <0.001 |

| April to May | 13.9 | 26.0 | 175.0 | 0.226 | <0.001 |

| May to June | 12.2 | −42.9 | −6.8 | <0.001 | |

| June to July | −4.3 | −2.8 | −29.3 | 0.712 | 0.005 |

| July to August | 9.1 | 34.3 | 58.6 | 0.013 | 0.15 |

| August to September | −37.5 | 0.0 | −32.6 | ||

| September to October | 23.3 | −8.5 | 22.6 | ||

| October to November | 16.2 | −30.2 | −34.2 | 0.752 | |

| November to December | 4.7 | 13.3 | 36.0 | 0.203 | 0.085 |

References

- Zhao, C.; Viana, A., Jr.; Wang, Y.; Wei, H.Q.; Yan, A.H.; Capasso, R. Otolaryngology during COVID-19: Preventive care and precautionary measures. Am. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Med. Surg. 2020, 41, 102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, M.J.; Cheng, Y. Policies Tackling the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Sociopolitical Perspective from Taiwan. Health Secur. 2020, 18, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Wu, K.C.C.; Gau, S.S.F. Mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 1421–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagiotos, A.; Petrikkos, G. Otolaryngology in the COVID-19 pandemic era: The impact on our clinical practice. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taiwan Centers for Disease Control CECC Confirms 2 More Imported COVID-19 Cases; Cases Arrive in Taiwan from the UK and India. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/-ShMvyrZbj9DKWNTBPCyxQ?typeid=158 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Chen, C.C.; Tseng, C.Y.; Choi, W.M.; Lee, Y.C.; Su, T.H.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Chang, C.M.; Weng, S.L.; Liu, P.H.; Tai, Y.L.; et al. Taiwan Government-Guided Strategies Contributed to Combating and Controlling COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, M.Y.; Yen, Y.F.; Chen, S.Y.; Lee, T.I.; Huang, K.H.; Chan, T.C.; Tung, T.H.; Hsu, L.Y.; Chiu, T.Y.; Hsueh, P.R.; et al. Learning from the past: Taiwan’s responses to COVID-19 versus SARS. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 110, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C. Taiwan’s experience in fighting COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.W.; Kao, C.T.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, P.F.; Liu, D.P. Risk assessment for COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.F.; Lai, C.C.; Chao, C.M.; Tang, H.J. Impact of COVID-19 preventative measures on dengue infections in Taiwan. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4063–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Yu, W.L. The COVID-19 pandemic and tuberculosis in Taiwan. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e159–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, I.; Hsu, J.L. Epidemiological observations on breaking COVID-19 transmission: From the experience of Taiwan. J Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterji, P.; Li, Y. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Outpatient Providers in the United States. Med Care 2021, 59, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patt, D.; Gordan, L.; Diaz, M.; Okon, T.; Grady, L.; Harmison, M.; Markward, N.; Sullivan, M.; Peng, J.; Zhou, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Care: How the Pandemic Is Delaying Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment for American Seniors. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2020, 4, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschol, J.; Gissel, C. COVID-19 pandemic and waiting times in outpatient specialist care in Germany: An empirical analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, F.-Y.; Huang, Y.-T.; Huang, W.-F. Using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Databases for pharmacoepidemiology research. J. Food Drug Anal. 2007, 15, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Z.; Guan, W.J.; Xie, Y.Q.; An, J.Y.; Peng, T.; Chen, R.C.; Zheng, J.P. Correlation between upper and lower airway inflammations in patients with combined allergic rhinitis and asthma syndrome: A comparison of patients initially presenting with allergic rhinitis and those initially presenting with asthma. Exp. Med. 2018, 15, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, J.; Minko, T. Recent Developments on Therapeutic and Diagnostic Approaches for COVID-19. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K. Adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines and measures to prevent them. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elibol, E. Otolaryngological symptoms in COVID-19. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 1233–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, K.S.; Costa, A.P.F.; Sarmento, A.C.A.; Freitas, C.L.; Gonçalves, A.K. Side effects of COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol of randomised trials. BMJ Open 2022, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichova, H.; Miller, M.E.; Derebery, M.J. Otologic Manifestations After COVID-19 Vaccination: The House Ear Clinic Experience. Otol. Neurotol. 2021, 42, e1213–e1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarzynska, M.B.; Matusiak, M.; Skarzynski, P.H. Adverse Audio-Vestibular Effects of Drugs and Vaccines Used in the Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19: A Review. Audiol. Res. 2022, 12, 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).