A Person-Environment Fit Model to Explain Information and Communication Technologies-Enabled After-Hours Work-Related Interruptions in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Person-Environment Fit Theory

2.2. Polychronicity

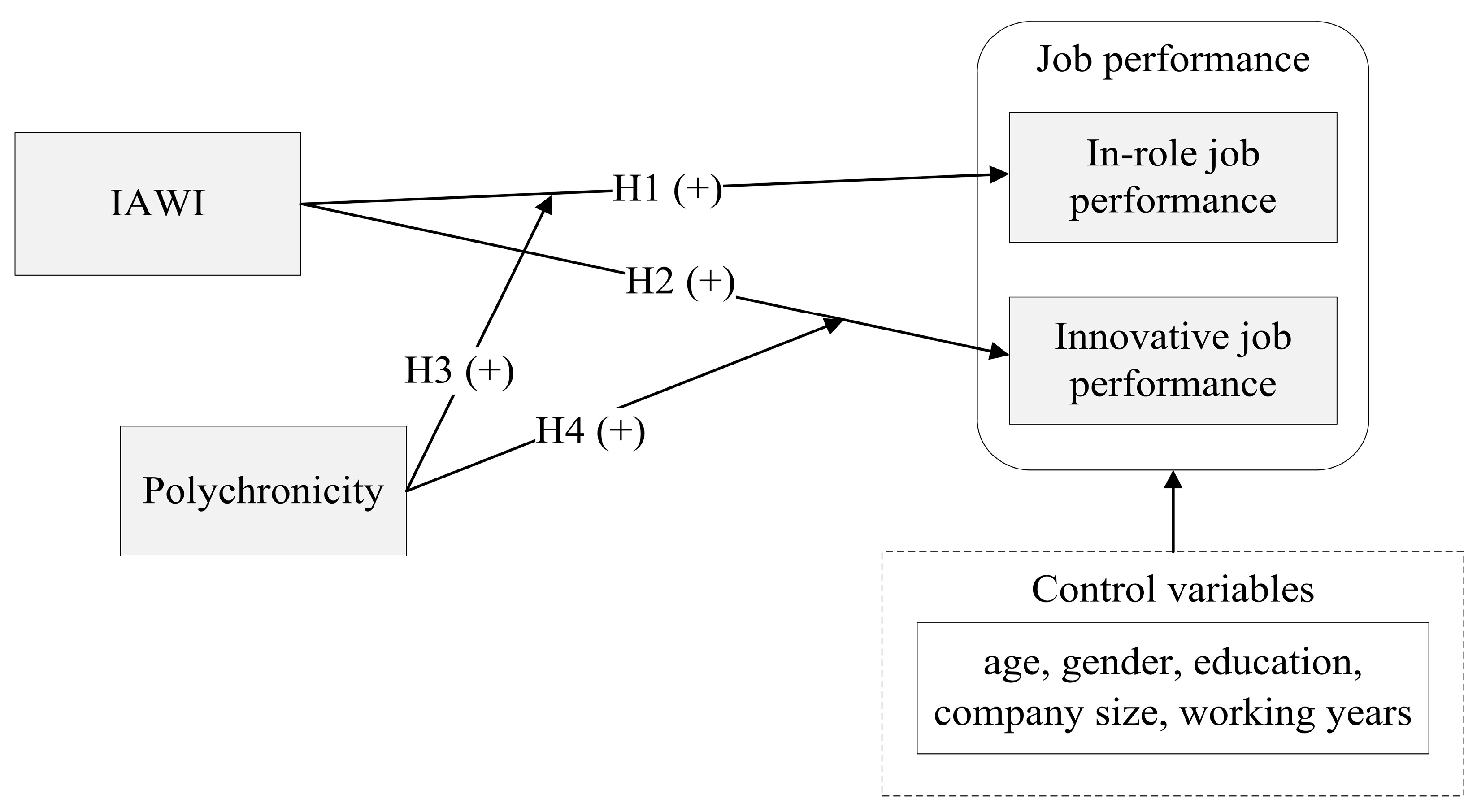

2.3. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

4. Analyses and Results

4.1. Statistical Data Analysis

4.2. Profile of Respondents

4.3. Results of Assessing the Measurement Model

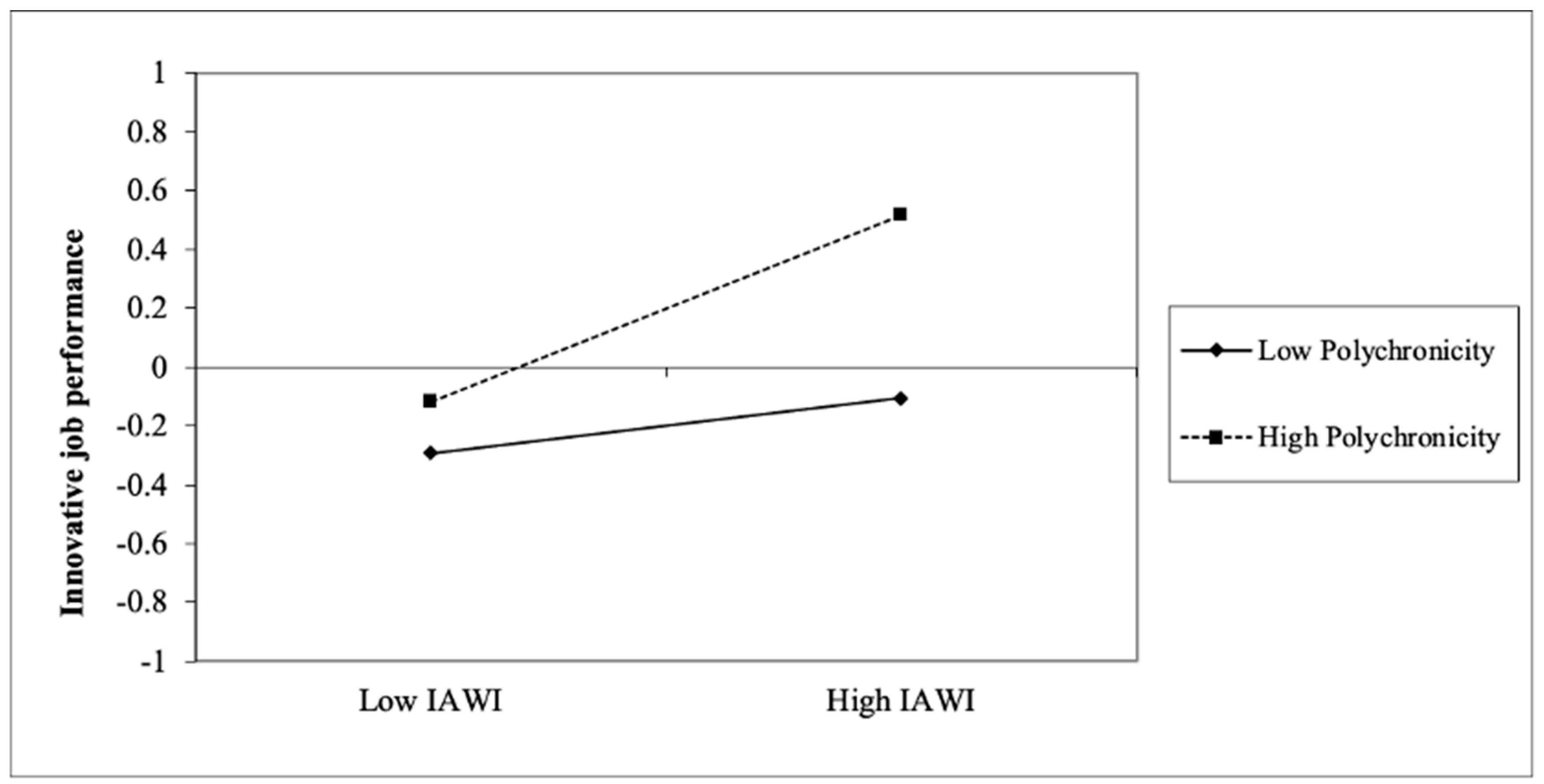

4.4. Results of the Analysis of the Path Model

5. Discussion of the Findings

6. Theoretical Contribution and Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Method | Context | Theories Used | Constructs in the Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | Survey | Use of mobile phones | N/A | Polychronicity, age, memories of past cognitive overload, memories of past emotional overload, information and communication technology-related overload |

| [82] | Survey | Work-home segmentation or integration | P-E fit theory | Work-family conflict, work-home conflict stress, segmentation preferences, supplies, job satisfaction |

| [58] | Survey | Social media usage | Uses and gratification theory, affordances theory | Social use, hedonic use, cognitive use, social capital (number of expressive ties, number of instrumental ties, relational dimension, cognitive dimension), job performance |

| [5] | Survey | Life interrupted | N/A | Interruption overload, after-hours work interruptions, work performance, work exhaustion |

| [6] | Survey | Use of a mobile device for work during family time (mWork) | Conservation of resources (COR) theory and family systems theory | mWork, job incumbent time-based work–life conflict (WFC), job incumbent strain-based WFC, job incumbent behavior-based WFC, incumbent, spousal resentment towards job incumbent’s organization, job incumbent organizational commitment, spousal commitment to job incumbent’s organization, job incumbent turnover intentions |

| [7] | Quantitative and qualitative research methodologies | E-mail as a stress in people’s life | N/A | Total hours worked, overload, coping, number of e-mails |

| [8] | Survey | Use of communication technologies beyond normal work hours | Boundary theory and related research on role integration | Communication technologies use after hours, affective commitment, job involvement, ambition, employee work-to-life conflict |

| [9] | Survey | Information technology-mediated interruptions | Conservation of resources theory | Congruent IT-mediated information interruption, incongruent IT-mediated information interruption, sequential processing, sequential processing, interruption overload, emotional exhaustion |

| [83] | Survey | Technology-mediated cross-domain interruptions | N/A | Technology mediated work-to-nonwork interruptions, work-to-nonwork conflict, nonwork performance, technology mediated nonwork-to-work Interruptions, nonwork-to-work conflict, work performance |

| [84] | Survey | Mobile usage | Rational actor theory | Level of uncertainty, cost/benefit evaluation, predicted interruption value, interruption response decision |

| [85] | Survey | Work–life Balance | Conservation of resources theory | Supervisors’ technology-mediated interruption behavior, information overload, sense of control, work/non-work exhaustion, work/non-work performance, supervisors’ work–life balance |

| [86] | Qualitative research methodology | Technology mediated work–life | Utilization of sociomaterial theory | Work–life balance, boundary management, technology, sociomateriality, power distance, collectivism |

| [87] | Survey | Conflict and quality of life in the digital age | Conservation of resources theory | Frequency of interruptions outside of work, frequency of interruptions at work mediated by technology, conflicts outside of work, conflicts at work, performance at work, performance outside of work |

| [88] | Survey | Online interruptions on task performance | Information richness theory | Perceived interruption, task performance, the rate’s types of interruptions, richness of interruption, the interruption rate on task performance |

| [89] | Survey | Telework | N/A | Fixed site telework, mobile telework, flexiwork, individual characteristics, organizational and technological contexts, the impacts on their work |

| [90] | Survey | Mobile devices in older users | Inhibitory deficit theory | Age, demands from technology-mediated interruptions, role-based stress, use of mobile technology for work |

| Construct | Source | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Information and communication technologies enabled after-hours work-related interruptions | Adapted from Chen and Karahanna [5] | To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? AHWI1: During my cyber-life, I frequently get interrupted about work-related matters through technology (by phone, e-mail, messaging, Dingding, WeChat). AHWI2. I frequently stop what I am doing during my cyber-life to initiate work-related activities through technology (by phone, e-mail, messaging, Dingding, WeChat). AHWI3. During my cyber-life, dealing with work-related interruptions initiated by others (by phone, e-mail, messaging, Dingding, WeChat) is time-consuming. AHWI4. Dealing with work interruptions I initiate during my cyber-life (by phone, e-mail, messaging, Dingding, WeChat) is time-consuming. |

| In-role job performance | Adapted from Williams and Anderson [59] | To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? RJP1. I adequately complete assigned duties during my in-role job. RJP2. I fulfill responsibilities specified in the job description during my in-role job. IJP3. I always complete the duties specified in my job description. IJP4. I meet all the formal performance requirements of the job. IJP5. I fulfill all responsibilities required by this job. IJP6. I successfully perform essential duties. |

| Innovative job performance | Adapted from Janssen and Van Yperen [60] | How often do you perform the following work activities? IJP1.I often create new ideas for improvements. IJP2. I often mobilize support for innovative ideas. IJP3. I often search out novel working methods. IJP4. I often transform innovative ideas into useful applications. |

| Polychronicity | Adapted from Slocombe and Bluedorn [61] | To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? PLO1.I like to juggle several activities at the same time. PLO2.I like to multi-task. |

References

- Microsoft. World Trend Index Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index/ (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- CNNIC. 50th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. 2022. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1742639780557516009&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Comin, D.A.; Cruz, M.; Cirera, X.; Lee, K.M.; Torres, J. Technology and Resilience; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhilian Recruiting; National School of Development of Peking University. Remote Stay-at-Home Reporting under the Impact of the Pandemic. 2022. Available online: http://www.100ec.cn/detail--6613405.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Chen, A.; Karahanna, E. Life Interrupted: The Effects of Technology-Mediated Work Interruptions on Work and Nonwork Outcomes. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.; Carlson, D.; Boswell, W.; Whitten, D.; Butts, M.M.; Kacmar, K.M. Tethered to work: A family systems approach linking mobile device use to turnover intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barley, S.R.; Meyerson, D.E.; Grodal, S. E-mail as a source and symbol of stress. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 887–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boswell, W.R.; Olson-Buchanan, J.B. The use of communication technologies after hours: The role of work attitudes and work-life conflict. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Bao, Y.; Zarifis, A. Investigating the impact of IT-mediated information interruption on emotional exhaustion in the workplace. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Lippe, T.; Lippényi, Z. Co-workers working from home and individual and team performance. New Technol. Work Employ. 2020, 35, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanaj, K.; Johnson, R.E.; Barnes, C.M. Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2014, 124, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Spicer, A. ‘You can checkout anytime, but you can never leave’: Spatial boundaries in a high commitment organization. Hum. Relat. 2004, 57, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, L.; Smart, R. The “myth of separate worlds”: An exploration of how mobile technology has redefined work-life balance. In Creating Balance? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, L.; Higgins, C.; Smart, R.; Stevenson, M. Mobile technology and boundary permeability. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 570–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittman, M.; Brown, J.E.; Wajcman, J. The mobile phone, perpetual contact and time pressure. Work Employ. Soc. 2009, 23, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Fields, D.; Luk, V. A cross-cultural test of a model of the work-family interface. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-C.; Kim, S.; Lee, H. Effect of work-related smartphone use after work on job burnout: Moderating effect of social support and organizational politics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 105, 106194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Ferdous, A.S.; Sekiguchi, T.; Sugianto, L.-F. The effect of mobile technology usage on work engagement and emotional exhaustion in Japan. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3315–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Chen, C.C.; Choi, J.; Zou, Y. Sources of work-family conflict: A Sino-US comparison of the effects of work and family demands. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Duan, Y. Communication technology use for work at home during off-job time and work–family conflict: The roles of family support and psychological detachment. Ann. Psychol. 2017, 33, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Fairness perceptions as a moderator in the curvilinear relationships between job demands, and job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, J.; Cloodt, M. Measuring innovative performance: Is there an advantage in using multiple indicators? Res. Policy 2003, 32, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, C.; Wiener, M.; Klett, S.; Sprenger, S. The impact of mental representations on ICT-related overload in the use of mobile phones. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 803–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale, J.M.; Hoover, C.S. Cell phones during nonwork time: A source of job demands and resources. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Xie, J.; Sun, L. Work-related use of information and communication technologies after-hours (W_ICTs) and employee innovation behavior: A dual-path model. Inf. Technol. People, 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Badke, W. Information overload? Maybe not. Online 2010, 34, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Caplan, R.D.; Van Harrison, R. Person-environment fit theory. Theor. Organ. Stress 1998, 28, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Tan, Y.-y.; Liu, Q.-m.; Ren, Y.-j.; Kawachi, I.; Li, L.-m.; Lv, J. Association between perceived urban built environment attributes and leisure-time physical activity among adults in Hangzhou, China. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, R.V. The individual differences tradition in counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 1992, 39, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R. An examination of competing versions of the person-environment fit approach to stress. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 292–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, J.R.; Van Harrison, R. Job demands and worker health: Three-dimensional reexamination of the relationship between person-environment fit and strain. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Reilly III, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of Individuals’fit at work: A meta-analysis OF person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T. The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time; Anchor: Albany, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bluedorn, A.C.; Kaufman, C.F.; Lane, P.M. How many things do you like to do at once? An introduction to monochronic and polychronic time. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1992, 6, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srite, M.; Karahanna, E.; Evaristo, J. Levels of culture and individual behaviour: An integrative perspective. Adv. Top. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2006, 5, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ragu-Nathan, T.; Tarafdar, M.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Tu, Q. The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bower, G.H. Mood and memory. Am. Psychol. 1981, 36, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, D.W. A restatement of the satisfaction-performance hypothesis. J. Manag. 1988, 14, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnake, M. Organizational citizenship: A review, proposed model, and research agenda. Hum. Relat. 1991, 44, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Bowler, W. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelsen, S.N.; Vatne, S.-H.; Mikalef, P.; Choudrie, J. Digital working during the COVID-19 pandemic: How task–technology fit improves work performance and lessens feelings of loneliness. Inf. Technol. People, 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Ma, H.; Zhou, Z.E.; Tang, H. Work-related use of information and communication technologies after hours (W_ICTs) and emotional exhaustion: A mediated moderation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 79, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Z. Off-time work-related smartphone use and bedtime procrastination of public employees: A cross-cultural study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J. With WeChat Work Groups, “It’s Like Having Meetings All the Time”! What Do a Thousand Respondents Think of This Phenomenon? Available online: https://www.jfdaily.com/news/detail?id=113900 (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, T.A.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Adekoya, O.D. Remote working and employee engagement: A qualitative study of British workers during the pandemic. Inf. Technol. People, 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meske, C.; Junglas, I. Investigating the elicitation of employees’ support towards digital workplace transformation. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 40, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, C.J.; Waller, M.J. Time for reflection: A critical examination of polychronicity. Hum. Perform. 2010, 23, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bluedorn, A.C. A unified model of turnover from organizations. Hum. Relat. 1982, 35, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali-Hassan, H.; Nevo, D.; Wade, M. Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O.; Van Yperen, N.W. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slocombe, T.E.; Bluedorn, A.C. Organizational behavior implications of the congruence between preferred polychronicity and experienced work-unit polychronicity. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 1999, 20, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. Understanding Culture’s Influence on Behavior; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, A. SmartPLS 2.0 (Beta); SmartPLS GmbH: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gudergan, S.P.; Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, A. Confirmatory tetrad analysis in PLS path modeling. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y. Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Straub, D.W. Validating instruments in MIS research. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cenfetelli, R.T.; Bassellier, G. Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D. Editor’s comments: An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lowry, P.B.; Vance, A.; Moody, G.; Beckman, B.; Read, A. Explaining and predicting the impact of branding alliances and web site quality on initial consumer trust of e-commerce web sites. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 24, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Romano, N.C.; Jenkins, J.L.; Guthrie, R.W. The CMC interactivity model: How interactivity enhances communication quality and process satisfaction in lean-media groups. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 155–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Rothbard, N.P. Social media or social minefield? Surviving in the new cyberspace era. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, C.E. Explaining the relationship between internet use and interpersonal trust: Taking into account motivation and information overload. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2008, 13, 550–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption ans use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, S.; Ahuja, M.; Sarker, S. Work–life conflict of globally distributed software development personnel: An empirical investigation using border theory. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 29, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E. Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Karahanna, E. Boundaryless technology: Understanding the effects of technology-mediated interruptions across the boundaries between work and personal life. AIS Trans. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2014, 6, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grandhi, S.; Jones, Q. Technology-mediated interruption management. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2010, 68, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, Z.; Ye, X. Effects of Supervisors’ Technology-Mediated Interruption Behavior on Their Work-Life Balance. In Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Pre-ICIS Workshop on HCI Research in MIS, Austin, TX, USA, 12 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- De Alwis, S.; Hernwall, P.; Adikaram, A.S. “It is ok to be interrupted; it is my job”–perceptions on technology-mediated work-life boundary experiences; a sociomaterial analysis. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 17, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maçada, A.; Freitas Junior, J.C.d.S.; Brinkhues, R.A.; Vasconcellos, S.D. Life Interrupted, but Performance Improved-Rethinking the Influence of Technology-Mediated Interruptions at Work and Personal Life. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, e0279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, E.C.; Ariel, Y. The Effects of Fragmented and Continuous Interruptions on Online Task Performance. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2022, 12, e202229. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, R.K.; Danziger, J.N. Which telework? Defining and testing a taxonomy of technology-mediated work at a distance. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2007, 25, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tams, S.; Grover, V.; Thatcher, J.; Ahuja, M. Grappling with modern technology: Interruptions mediated by mobile devices impact older workers disproportionately. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2021, 20, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency (Percent) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (enter age): | 32.04 (14.82) | ||

| Gender: | 1.49 (0.50) | ||

| Male | 141 | 50.9% | |

| Female | 136 | 49.1% | |

| Education: | 4.05 (0.69) | ||

| Less than high school/secondary school | 2 | 0.7% | |

| High school/secondary school | 5 | 1.8% | |

| Associate degree/Higher Diploma | 23 | 8.3% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 204 | 73.6% | |

| Master’s degree | 34 | 12.3% | |

| Doctorate/Ph.D. | 9 | 3.3% | |

| Income | 3.46 (0.88) | ||

| Below 3500 | 4 | 1.4% | |

| 3501–5000 | 22 | 7.9% | |

| 5001–10,000 | 125 | 45.1% | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 100 | 36.1% | |

| 20,001–50,000 | 20 | 7.2% | |

| Above 50,001 | 6 | 2.2% | |

| Industry | 4.67 (3.09) | ||

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 6 | 2.2% | |

| Internet/information systems | 93 | 33.6% | |

| Construction/manufacturing | 49 | 17.7% | |

| Transportation, storage, postal and courier services | 20 | 7.2% | |

| Import/export and wholesale | 15 | 5.4% | |

| Retail trades | 11 | 4% | |

| Financial, insurance and real estate activities | 29 | 10.5% | |

| Accommodation and food service activities | 14 | 5.1% | |

| Public administration | 11 | 4% | |

| Education | 12 | 4.3% | |

| Health | 4 | 1.4% | |

| Others | 13 | 4.7% | |

| Company size: | 2.29 (0.92) | ||

| Below 100 | 50 | 18.1% | |

| 100–500 | 137 | 49.5% | |

| 501–1000 | 51 | 18.4% | |

| Over 1000 | 139 | 14.1% | |

| Working years | 3.75 (0.96) | ||

| Below 1 year | 5 | 1.8% | |

| 1–3 years | 29 | 10.5% | |

| 3–5 years (not include 3 years) | 53 | 19.1% | |

| 5–10 years (not include 5 years) | 132 | 47.7% | |

| Above 10 years | 58 | 20.9% | |

| Occupation-ranking | 1.81 (0.92) | ||

| Employee | 136 | 49.1% | |

| Basic-level manager | 66 | 23.8% | |

| Middle-level manager | 68 | 24.5% | |

| Senior leadership | 5 | 1.8% | |

| Other | 2 | 0.7% | |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance (%) | Cumulative (%) | |

| 1 | 4.237 | 26.482 | 26.482 |

| 2 | 2.292 | 14.326 | 40.808 |

| 3 | 1.835 | 11.47 | 52.277 |

| 4 | 1.752 | 10.953 | 63.23 |

| 5 | 0.894 | 5.586 | 68.816 |

| 6 | 0.832 | 5.199 | 74.015 |

| 7 | 0.668 | 4.175 | 78.19 |

| 8 | 0.573 | 3.583 | 81.773 |

| 9 | 0.545 | 3.408 | 85.181 |

| 10 | 0.475 | 2.969 | 88.151 |

| 11 | 0.426 | 2.66 | 90.811 |

| 12 | 0.395 | 2.467 | 93.278 |

| 13 | 0.374 | 2.34 | 95.618 |

| 14 | 0.296 | 1.851 | 97.47 |

| 15 | 0.217 | 1.355 | 98.825 |

| 16 | 0.188 | 1.175 | 100 |

| Extracted sums of squared loadings | |||

| 1 | 4.237 | 26.482 | 26.482 |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Substantive Factor Loading (R1) | R12 | Method Factor Loading (R2) | R22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information and communication technologies enabled after-hours work-related interruptions (IAWI) | IAWI1 | 0.884 | 0.7678 | 0.590 | 0.0290 | 0.001 |

| IAWI2 | 0.859 | 0.7018 | 0.493 | 0.0657 | 0.004 | |

| IAWI3 | 0.617 | 0.8287 | 0.687 | −0.0582 | 0.003 | |

| IAWI4 | 0.602 | 0.7916 | 0.627 | −0.0295 | 0.001 | |

| In-role job performance (RJP) | RJP1 | 0.769 | 0.7221 | 0.521 | −0.0121 | 0.000 |

| RJP2 | 0.677 | 0.7403 | 0.548 | −0.0284 | 0.001 | |

| RJP3 | 0.660 | 0.6515 | 0.424 | −0.0026 | 0.000 | |

| RJP4 | 0.697 | 0.8247 | 0.680 | −0.0954 | 0.009 | |

| RJP5 | 0.769 | 0.6873 | 0.472 | −0.0002 | 0.000 | |

| RJP6 | 0.708 | 0.6882 | 0.474 | 0.1274 | 0.016 | |

| Innovative job performance (IJP) | IJP1 | 0.837 | 0.8662 | 0.750 | −0.0470 | 0.002 |

| IJP2 | 0.800 | 0.8429 | 0.710 | −0.0818 | 0.007 | |

| IJP3 | 0.819 | 0.7765 | 0.603 | 0.0680 | 0.005 | |

| IJP4 | 0.787 | 0.7606 | 0.579 | 0.0575 | 0.003 | |

| Polychronicity (POL) | POL1 | 0.909 | 0.9466 | 0.896 | 0.0247 | 0.001 |

| POL2 | 0.969 | 0.9388 | 0.881 | −0.0247 | 0.001 | |

| Average | 0.621 | 0.003 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IAWI | 5.07 | 1.14 | 0.776 | 0.840 | 0.566 | 0.752 | |||

| 2. RJP | 5.92 | 0.70 | 0.812 | 0.859 | 0.511 | 0.125 | 0.715 | ||

| 3. IJP | 5.59 | 0.89 | 0.823 | 0.883 | 0.657 | 0.190 | 0.400 | 0.811 | |

| 4. POL | 4.37 | 1.57 | 0.875 | 0.937 | 0.883 | −0.020 | 0.125 | −0.075 | 0.940 |

| Tested Path | Path Coefficient (β) | t-Value (df = 277) | Hypothesis Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | |||

| H1. IAWI → In-role job performance | 0.139 | 2.020 * | Yes |

| H2. IAWI → Innovative job performance | 0.200 | 3.013 ** | Yes |

| H3. IAWI * Polychronicity → In-role job performance | −0.093 | 1.762 | Not supported |

| H4. IAWI * Polychronicity → Innovative job performance | 0.112 | 2.143 * | Yes |

| Covariates | |||

| Age → In-role job performance | 0.041 | 0.874 | |

| Gender → In-role job performance | 0.089 | 0.523 | |

| Education → In-role job performance | −0.018 | 0.401 | |

| Income → In-role job performance | 0.152 * | 1.971 | |

| Industry → In-role job performance | −0.052 | 1.062 | |

| Company size → In-role job performance | −0.055 | 1.101 | |

| Working years → In-role job performance | 0.127 | 1.545 | |

| Occupation-ranking → In-role job performance | −0.089 | 1.421 | |

| Age → Innovative job performance | −0.031 | 0.303 | |

| Gender → Innovative job performance | 0.035 | 0.842 | |

| Education → Innovative job performance | −0.092 | 1.509 | |

| Income → Innovative job performance | 0.170 * | 2.284 | |

| Industry → Innovative job performance | −0.056 | 1.139 | |

| Company size → Innovative job performance | 0.068 | 1.322 | |

| Working years → Innovative job performance | −0.009 | 0.135 | |

| Occupation-ranking → Innovative job performance | 0.123 | 1.802 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Huang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q. A Person-Environment Fit Model to Explain Information and Communication Technologies-Enabled After-Hours Work-Related Interruptions in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043456

Zhang S, Huang F, Zhang Y, Li Q. A Person-Environment Fit Model to Explain Information and Communication Technologies-Enabled After-Hours Work-Related Interruptions in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043456

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shanshan, Fengchun Huang, Yuting Zhang, and Qiwen Li. 2023. "A Person-Environment Fit Model to Explain Information and Communication Technologies-Enabled After-Hours Work-Related Interruptions in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043456

APA StyleZhang, S., Huang, F., Zhang, Y., & Li, Q. (2023). A Person-Environment Fit Model to Explain Information and Communication Technologies-Enabled After-Hours Work-Related Interruptions in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043456