Prioritizing Neighbourhood Amenities to Enhance Neighbourhood Satisfaction: A Case Study in Wuhan, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Neighbourhood Satisfaction, Amenities, and Quality of Life

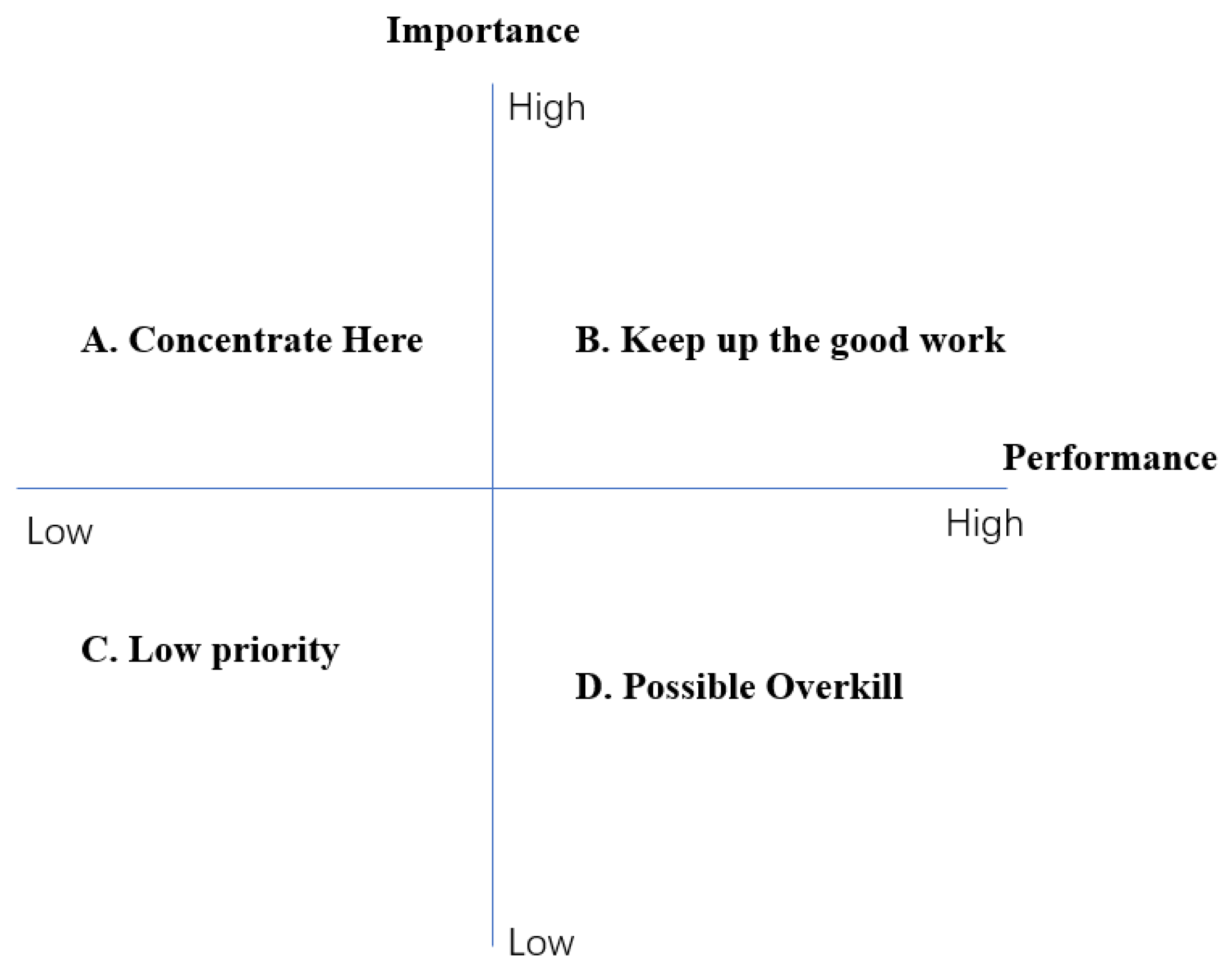

2.2. The Importance–Performance Analysis and Three-Factor Theory of Satisfaction

3. Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Framework

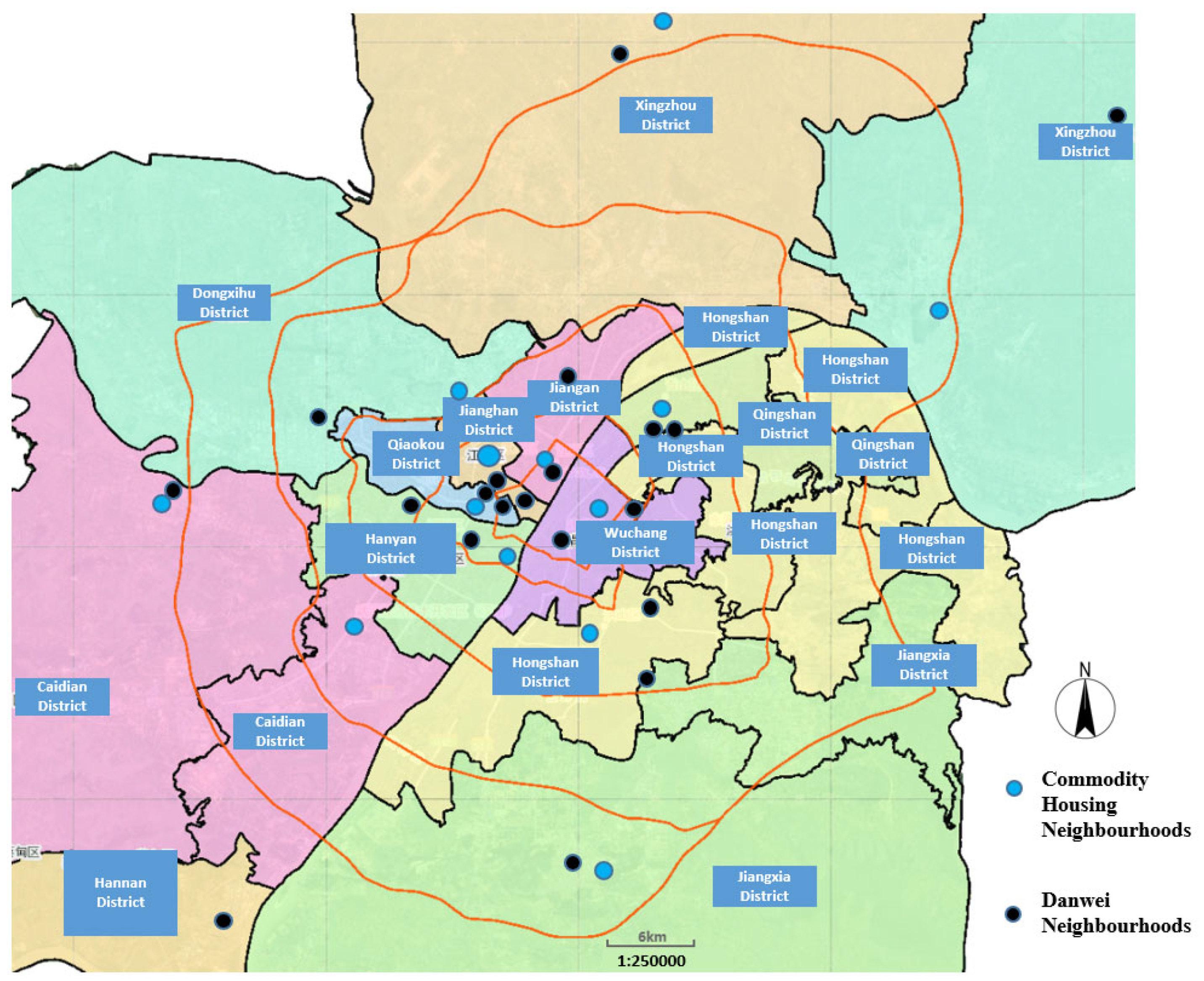

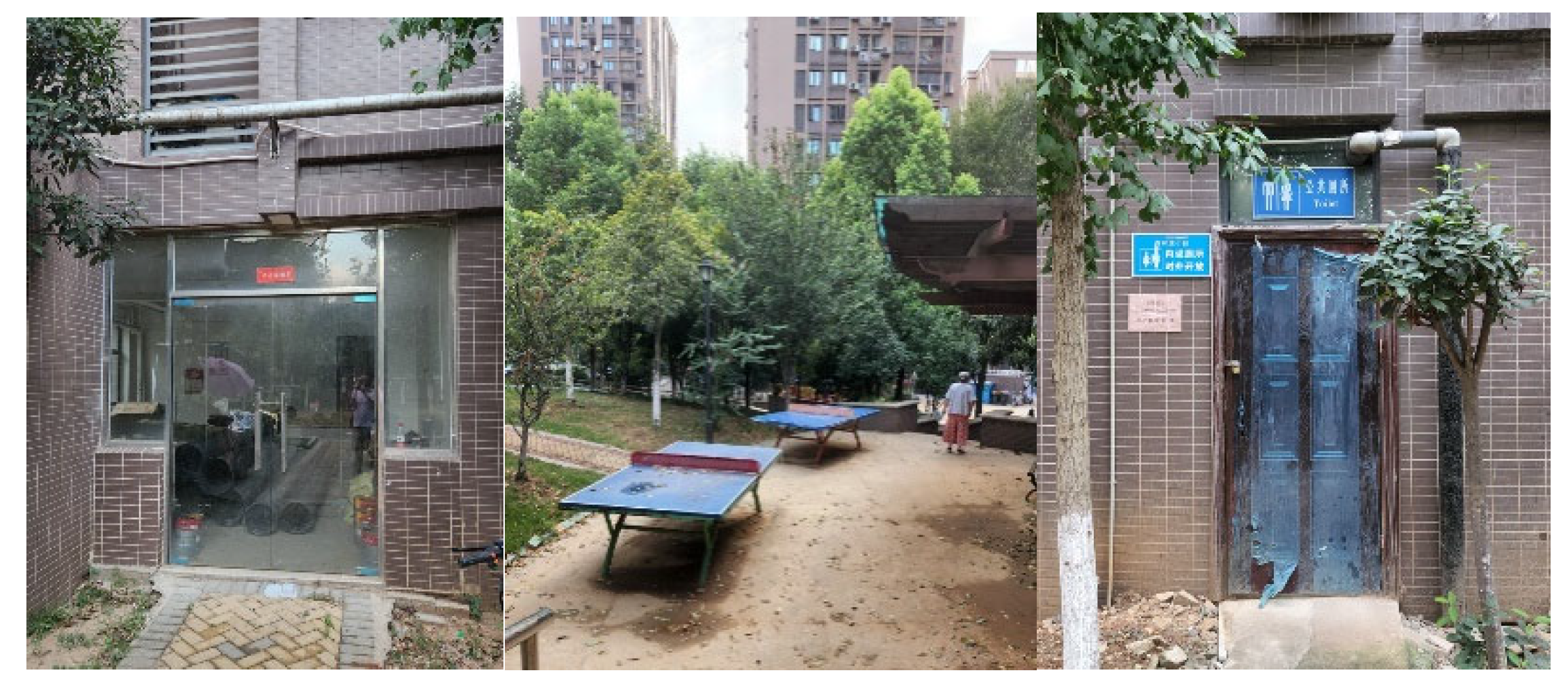

3.2. Study Area and Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

- (1)

- Aged 18 or above;

- (2)

- Permanent resident who is now living in the studied neighbourhood, excluding administrative staff or businessman on the street.

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results of Descriptive Analysis

4.1. Respondents’ Socioeconomic Characteristics

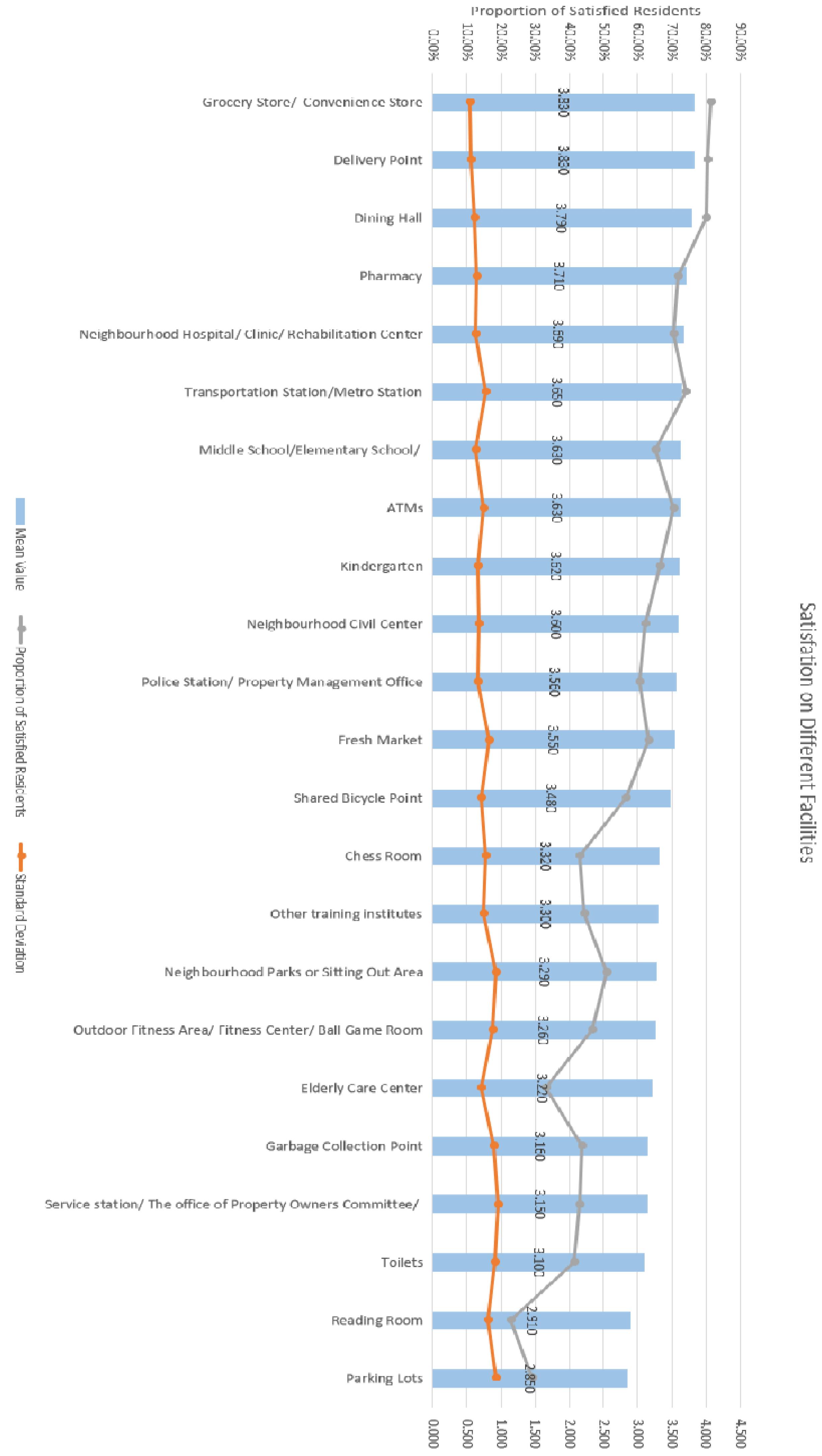

4.2. Respondents’ Usage, Satisfaction, and Demands for Amenities

4.3. Higher Level of Satisfaction with Amenities in Commodity-Housing Neighbourhoods Than in Danwei Neighbourhoods

4.4. Frequently Used and Desirable Amenities for Different Age Groups

5. Prioritizing Neighbourhood Amenities to Enhance Elderly Satisfaction in Old Danwei Neighbourhoods: Application of the IPA–Kano Model

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

6.1. Pattern of Amenity Usage

6.2. Problems of the Provision of Amenities in Commodity-Housing and Danwei Neighbourhoods

6.3. Policy Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

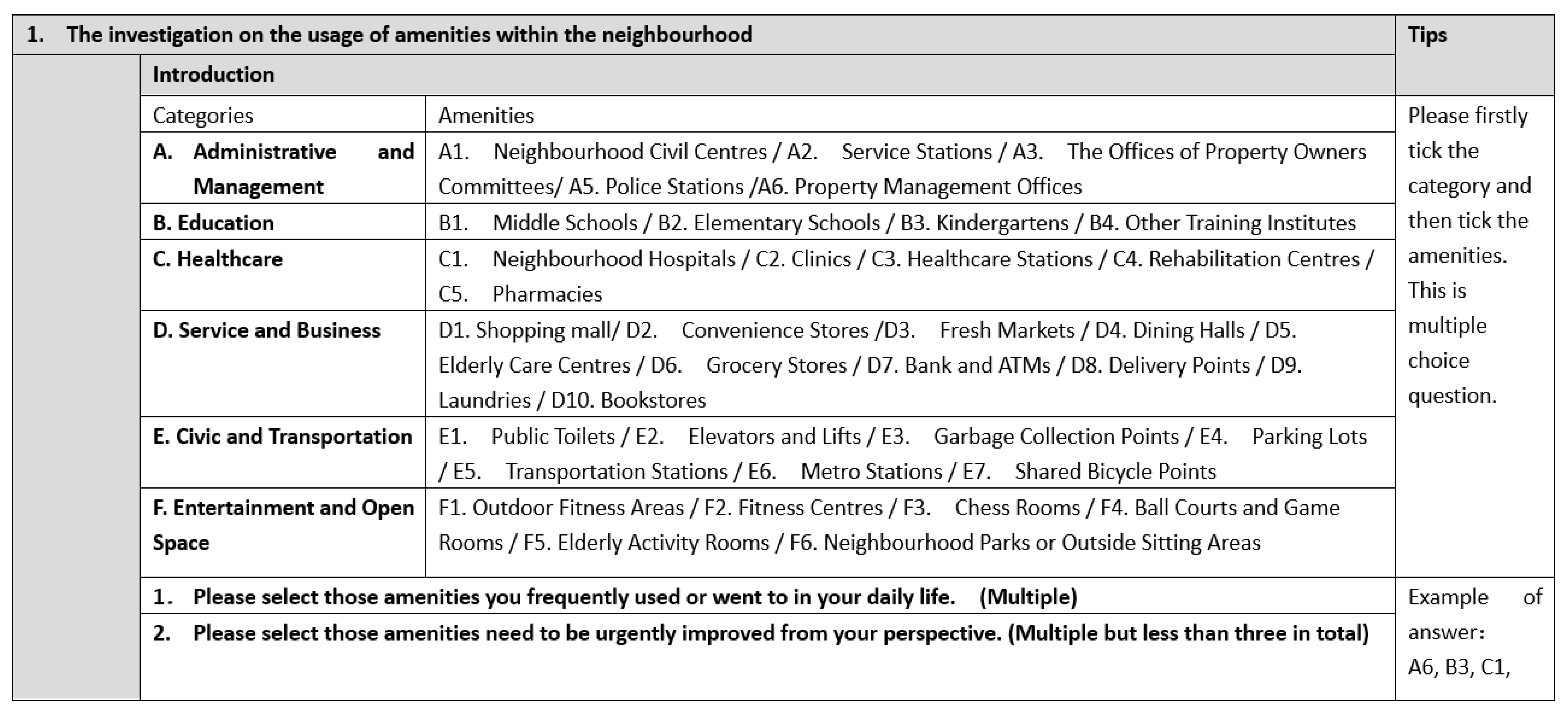

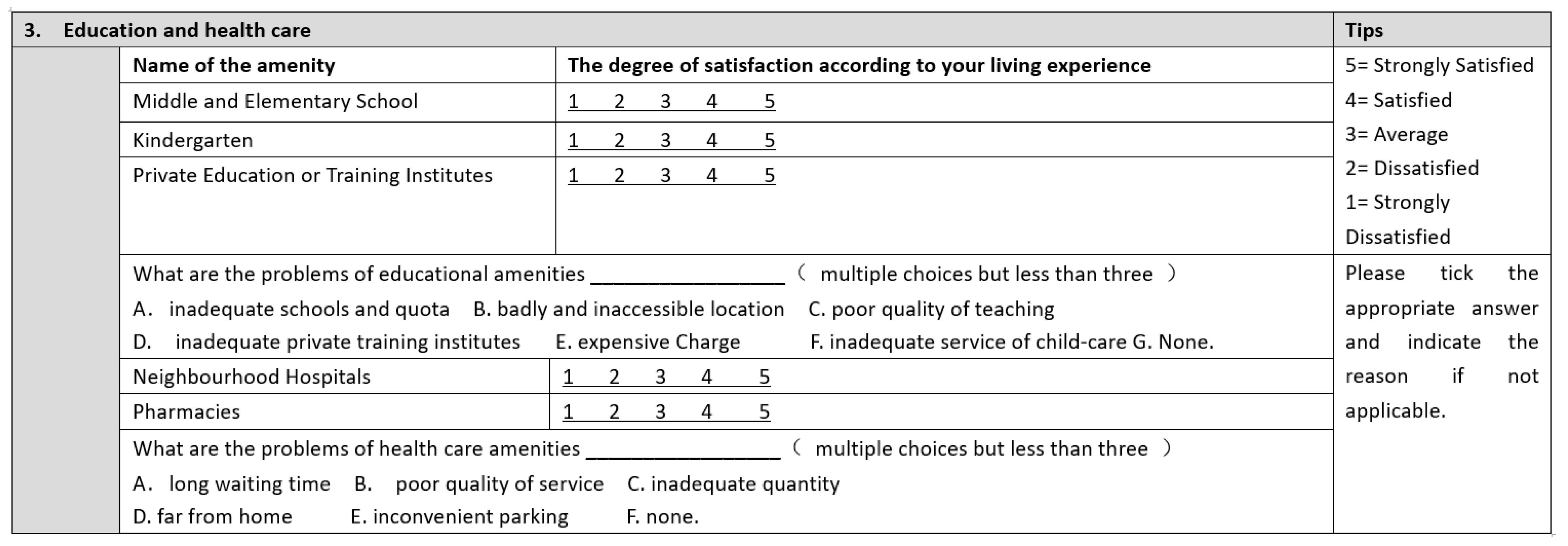

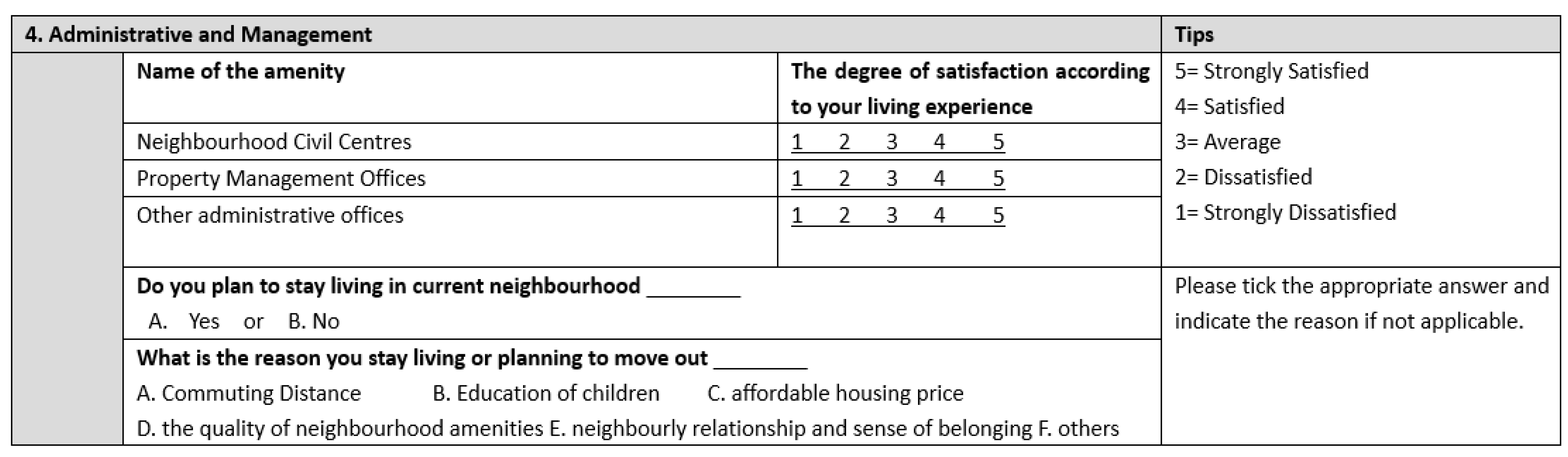

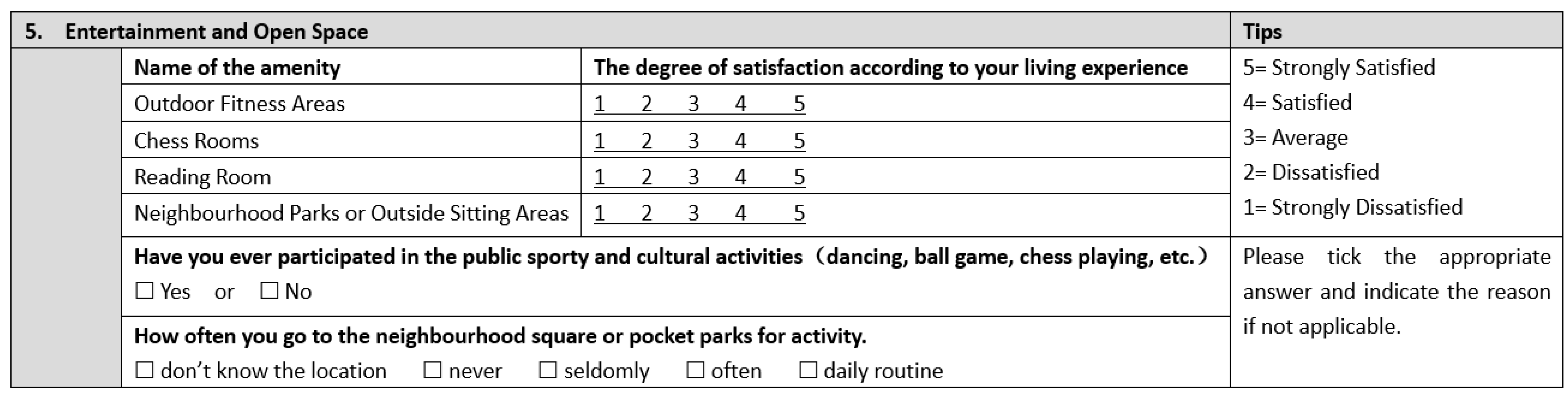

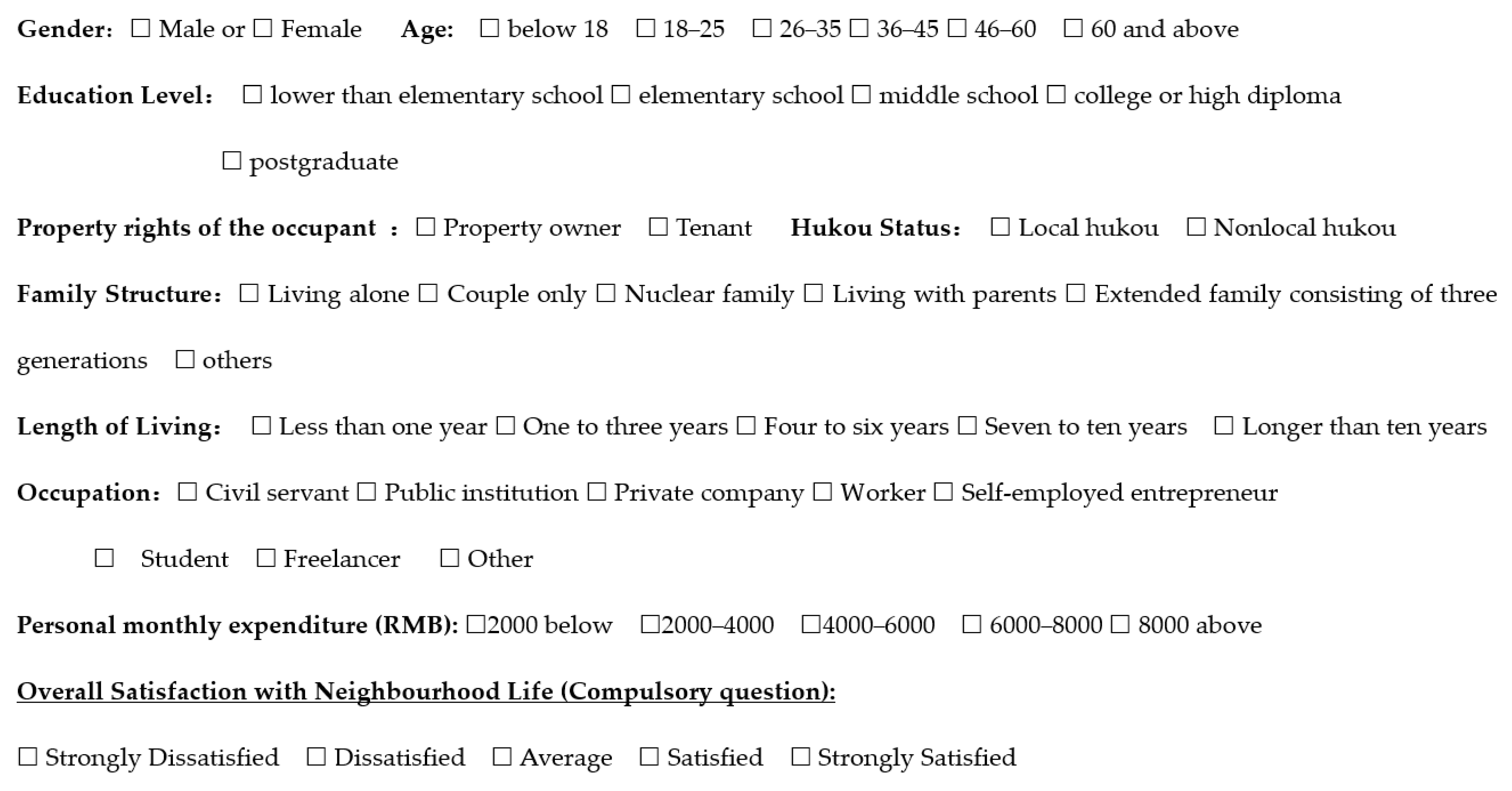

Appendix A. Questionnaire Survey Adopted in this Study: The Investigation of Residents’ Perceptions on the Usage of Neighbourhood Amenities

Appendix B. Results of Ordinal Logistical Regression

| Model | −2 Log Likelihood | Chi-Square | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Only | 1103.154 | |||

| Final | 723.85 | 379.304 | 105 | 0.000 |

| Chi-Square | df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | 2184.723 | 1799 | 0.000 |

| Deviance | 721.077 | 1799 | 1.000 |

| Cox and Snell | 0.545 |

| Nagelkerke | 0.606 |

| McFadden | 0.343 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | Wald | df | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Threshold | (overall neighbourhood satisfaction =1) | −85.656 | 60.675 | 1.993 | 1 | 0.158 | −204.577 | 33.266 |

| (overall neighbourhood satisfaction = 2) | −7.989 | 12.309 | 0.421 | 1 | 0.516 | −32.115 | 16.137 | |

| (overall neighbourhood satisfaction = 3) | −0.573 | 12.316 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.963 | −24.713 | 23.566 | |

| (overall neighbourhood satisfaction = 4) | 10.052 | 12.216 | 0.677 | 1 | 0.411 | −13.892 | 33.995 | |

| Location | [Convenience Stores = 2] | −1.548 | 1.626 | 0.906 | 1 | 0.341 | −4.734 | 1.639 |

| [Convenience Stores = 3] | −4.268 | 1.419 | 9.047 | 1 | 0.003 | −7.049 | −1.487 | |

| [Convenience Stores = 4] | −1.961 | 1.158 | 2.870 | 1 | 0.090 | −4.230 | 0.308 | |

| [Convenience Stores = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Fresh Markets = 1] | 3.968 | 2.075 | 3.657 | 1 | 0.056 | −0.099 | 8.034 | |

| [Fresh Markets = 2] | 2.717 | 1.011 | 7.221 | 1 | 0.007 | 0.735 | 4.699 | |

| [Fresh Markets = 3] | 3.181 | 1.011 | 9.898 | 1 | 0.002 | 1.199 | 5.162 | |

| [Fresh Markets = 4] | 2.521 | 0.869 | 8.410 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.817 | 4.224 | |

| [Fresh Markets = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Dining Halls = 2] | −1.220 | 1.128 | 1.170 | 1 | 0.279 | −3.432 | 0.991 | |

| [Dining Halls = 3] | −1.448 | 0.939 | 2.378 | 1 | 0.123 | −3.288 | 0.392 | |

| [Dining Halls = 4] | −1.367 | 0.821 | 2.772 | 1 | 0.096 | −2.976 | 0.242 | |

| [Dining Halls = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Elderly Care Centres = 1] | −7.037 | 2.308 | 9.296 | 1 | 0.002 | −11.560 | −2.513 | |

| [Elderly Care Centres = 2] | −3.096 | 1.788 | 2.0998 | 1 | 0.083 | −6.601 | 0.408 | |

| [Elderly Care Centres = 3] | −0.657 | 1.710 | 0.147 | 1 | 0.701 | −4.009 | 2.695 | |

| [Elderly Care Centres = 4] | −0.724 | 1.670 | 0.188 | 1 | 0.665 | −3.998 | 2.550 | |

| [Elderly Care Centres = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Bank and ATMs = 1] | −1.020 | 8.681 | 0.014 | 1 | 0.907 | −18.035 | 15.996 | |

| [Bank and ATMs = 2] | 3.569 | 2.025 | 3.107 | 1 | 0.078 | −0.399 | 7.537 | |

| [Bank and ATMs = 3] | 4.026 | 1.997 | 4.063 | 1 | 0.044 | 0.111 | 7.941 | |

| [Bank and ATMs = 4] | 5.379 | 1.996 | 7.261 | 1 | 0.007 | 1.466 | 9.292 | |

| [Bank and ATMs = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Delivery Points = 1] | 0.037 | 11.639 | .000 | 1 | 0.997 | −22.775 | 22.849 | |

| [Delivery Points = 2] | −0.281 | 1.909 | .022 | 1 | 0.883 | −4.022 | 3.460 | |

| [Delivery Points = 3] | −2.875 | 1.432 | 4.031 | 1 | 0.045 | −5.682 | −0.068 | |

| [Delivery Points = 4] | −1.436 | 1.281 | 1.256 | 1 | 0.262 | −3.946 | 1.075 | |

| [Delivery Points = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Middle and Elementary Schools = 2] | −1.750 | 2.514 | 0.485 | 1 | 0.486 | −6.679 | 3.178 | |

| [Middle and Elementary Schools = 3] | −1.324 | 2.384 | 0.308 | 1 | 0.579 | −5.997 | 3.349 | |

| [Middle and Elementary Schools = 4] | −2.311 | 2.368 | 0.953 | 1 | 0.329 | −6.952 | 2.329 | |

| [Middle and Elementary Schools = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Kindergartens = 1] | −3.035 | 3.085 | 0.968 | 1 | 0.325 | −9.081 | 3.011 | |

| [Kindergartens = 2] | 0.251 | 1.670 | 0.023 | 1 | 0.880 | −3.021 | 3.524 | |

| [Kindergartens = 3] | 0.491 | 1.640 | 0.090 | 1 | 0.765 | −2.723 | 3.706 | |

| [Kindergartens = 4] | −0.776 | 1.578 | 0.242 | 1 | 0.623 | −3.868 | 2.317 | |

| [Kindergartens = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Other Training Institutes = 1] | −42.234 | 199.530 | .045 | 1 | 0.832 | −433.306 | 348.838 | |

| [Other Training Institutes = 2] | 6.788 | 4.474 | 2.302 | 1 | 0.129 | −1.981 | 15.557 | |

| [Other Training Institutes = 3] | 5.280 | 4.411 | 1.433 | 1 | 0.231 | −3.366 | 13.927 | |

| [Other Training Institutes = 4] | 6.226 | 4.476 | 1.935 | 1 | 0.164 | −2.547 | 14.998 | |

| [Other Training Institutes = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Neighbourhood Hospitals and Clinics = 1] | 8.591 | 3.394 | 6.407 | 1 | 0.011 | 1.939 | 15.243 | |

| [Neighbourhood Hospitals and Clinics = 2] | 0.159 | 1.105 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.886 | −2.007 | 2.324 | |

| [Neighbourhood Hospitals and Clinics = 3] | 2.396 | 1.053 | 5.176 | 1 | 0.023 | 0.332 | 4.459 | |

| [Neighbourhood Hospitals and Clinics = 4] | 0.673 | 0.924 | 0.531 | 1 | 0.466 | −1.138 | 2.483 | |

| [Neighbourhood Hospitals and Clinics = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Pharmacies = 1] | −5.362 | 3.336 | 2.584 | 1 | 0.108 | −11.900 | 1.176 | |

| [Pharmacies = 2] | −7.030 | 1.529 | 21.143 | 1 | 0.000 | −10.026 | −4.033 | |

| [Pharmacies = 3] | −5.379 | 1.314 | 16.751 | 1 | 0.000 | −7.955 | −2.803 | |

| [Pharmacies = 4] | −5.531 | 1.236 | 20.021 | 1 | 0.000 | −7.953 | −3.108 | |

| [Pharmacies = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Neighbourhood Civil Centres = 1] | −4.404 | 3.097 | 2.021 | 1 | .155 | −10.475 | 1.667 | |

| [Neighbourhood Civil Centres = 2] | −4.686 | 1.842 | 6.475 | 1 | 0.011 | −8.295 | −1.077 | |

| [Neighbourhood Civil Centres = 3] | −2.910 | 1.683 | 2.989 | 1 | 0.084 | −6.209 | 0.389 | |

| [Neighbourhood Civil Centres = 4] | −1.761 | 1.610 | 1.196 | 1 | 0.274 | −4.917 | 1.395 | |

| [Neighbourhood Civil Centres = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [The Offices of Property Owners Committees and Property Management = 1] | 2.730 | 1.833 | 2.217 | 1 | 0.136 | −0.863 | 6.324 | |

| [The Offices of Property Owners Committees and Property Management = 2] | 1.514 | 1.469 | 1.061 | 1 | 0.303 | −1.366 | 4.394 | |

| [The Offices of Property Owners Committees and Property Management = 3] | 3.716 | 1.449 | 6.578 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.876 | 6.556 | |

| [The Offices of Property Owners Committees and Property Management = 4] | 4.230 | 1.427 | 8.783 | 1 | 0.003 | 1.433 | 7.028 | |

| [The Offices of Property Owners Committees and Property Management = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Other Administrative facilities = 1] | −3.916 | 4.117 | 0.905 | 1 | 0.342 | −11.986 | 4.154 | |

| [Other Administrative facilities = 2] | 3.240 | 2.370 | 1.869 | 1 | 0.172 | −1.405 | 7.885 | |

| [Other Administrative facilities = 3] | −0.508 | 2.130 | 0.057 | 1 | 0.812 | −4.682 | 3.666 | |

| [Other Administrative facilities = 4] | −0.131 | 2.100 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.950 | −4.246 | 3.984 | |

| [Other Administrative facilities = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Outdoor and indoor fitness areas = 1] | −5.275 | 3.144 | 2.816 | 1 | 0.093 | −11.436 | 0.886 | |

| [Outdoor and indoor fitness areas = 2] | −4.341 | 1.929 | 5.065 | 1 | 0.024 | −8.122 | −0.561 | |

| [Outdoor and indoor fitness areas = 3] | −4.315 | 1.888 | 5.224 | 1 | 0.022 | −8.016 | −0.615 | |

| [Outdoor and indoor fitness areas = 4] | −3.237 | 1.777 | 3.318 | 1 | 0.069 | −6.719 | 0.246 | |

| [Outdoor and indoor fitness areas = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Entertainment Room = 1] | −3.474 | 2.563 | 1.836 | 1 | 0.175 | −8.498 | 1.551 | |

| [Entertainment Room = 2] | −2.505 | 1.390 | 3.249 | 1 | 0.071 | −5.229 | 0.219 | |

| [Entertainment Room = 3] | −2.343 | 1.355 | 2.992 | 1 | 0.084 | −4.998 | 0.312 | |

| [Entertainment Room = 4] | −1.728 | 1.279 | 1.824 | 1 | 0.177 | −4.234 | 0.779 | |

| [Entertainment Room = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Reading Rooms = 1] | 2.675 | 1.924 | 1.934 | 1 | 0.164 | −1.096 | 6.447 | |

| [Reading Rooms = 2] | 2.202 | 1.420 | 2.404 | 1 | 0.121 | −0.582 | 4.985 | |

| [Reading Rooms = 3] | 0.714 | 1.369 | 0.272 | 1 | 0.602 | −1.969 | 3.396 | |

| [Reading Rooms = 4] | 1.058 | 1.397 | 0.573 | 1 | 0.449 | −1.681 | 3.797 | |

| [Reading Rooms = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Neighbourhood Parks or Outside Sitting Areas = 1] | −3.038 | 2.476 | 1.505 | 1 | 0.220 | −7.892 | 1.816 | |

| [Neighbourhood Parks or Outside Sitting Areas = 2] | 0.114 | 1.254 | 0.008 | 1 | 0.927 | −2.343 | 2.572 | |

| [Neighbourhood Parks or Outside Sitting Areas = 3] | −0.392 | 1.203 | 0.106 | 1 | 0.744 | −2.750 | 1.966 | |

| [Neighbourhood Parks or Outside Sitting Areas = 4] | 1.263 | 1.156 | 1.192 | 1 | 0.275 | −1.004 | 3.529 | |

| [Neighbourhood Parks or Outside Sitting Areas = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Squares = 1] | −5.162 | 2.188 | 5.564 | 1 | 0.018 | −9.451 | −0.873 | |

| [Squares = 2] | 0.458 | 0.527 | 0.756 | 1 | 0.385 | −0.574 | 1.490 | |

| [Squares = 3] | 2.333 | 1.106 | 4.448 | 1 | 0.035 | 0.165 | 4.501 | |

| [Squares = 4] | 1.732 | 0.520 | 11.083 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.712 | 2.751 | |

| [Squares = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Garbage Collection Points = 1] | 2.539 | 2.251 | 1.272 | 1 | 0.259 | −1.874 | 6.952 | |

| [Garbage Collection Points = 2] | −0.704 | 1.501 | 0.220 | 1 | 0.639 | −3.646 | 2.239 | |

| [Garbage Collection Points = 3] | 0.463 | 1.518 | 0.093 | 1 | 0.761 | −2.513 | 3.438 | |

| [Garbage Collection Points = 4] | 1.781 | 1.461 | 1.485 | 1 | 0.223 | −1.083 | 4.645 | |

| [Garbage Collection Points = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Parking Lots = 1] | −6.206 | 2.750 | 5.092 | 1 | 0.024 | −11.595 | −0.816 | |

| [Parking Lots = 2] | −3.112 | 2.610 | 1.422 | 1 | 0.233 | −8.227 | 2.002 | |

| [Parking Lots = 3] | −2.567 | 2.600 | 0.974 | 1 | 0.324 | −7.663 | 2.530 | |

| [Parking Lots = 4] | −4.994 | 2.677 | 3.479 | 1 | 0.062 | −10.241 | 0.254 | |

| [Parking Lots = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Transportation Stations = 1] | −4.509 | 2.111 | 4.564 | 1 | 0.033 | −8.646 | −0.372 | |

| [Transportation Stations = 2] | −1.556 | 1.603 | 0.942 | 1 | 0.332 | −4.698 | 1.586 | |

| [Transportation Stations = 3] | −4.477 | 1.580 | 8.028 | 1 | 0.005 | −7.574 | −1.380 | |

| [Transportation Stations = 4] | −2.777 | 1.483 | 3.505 | 1 | 0.061 | −5.684 | 0.130 | |

| [Transportation Stations = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Shared Bicycle Points = 1] | −1.504 | 6.592 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.820 | −14.424 | 11.416 | |

| [Shared Bicycle Points = 2] | 0.925 | 5.144 | 0.032 | 1 | 0.857 | −9.156 | 11.007 | |

| [Shared Bicycle Points = 3] | 0.270 | 5.109 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.958 | −9.744 | 10.284 | |

| [Shared Bicycle Points = 4] | 0.297 | 5.104 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.954 | −9.707 | 10.300 | |

| [Shared Bicycle Points = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Gender = 1] | −1.482 | 0.430 | 11.851 | 1 | 0.001 | −2.325 | −0.638 | |

| [Gender = 2] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Education= 2] | −0.264 | 1.057 | 0.063 | 1 | 0.802 | −2.335 | 1.807 | |

| [Education = 3] | 0.028 | 0.856 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.974 | −1.650 | 1.706 | |

| [Education = 4] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Family Structure = 1] | 0.631 | 1.406 | 0.201 | 1 | 0.654 | −2.124 | 3.386 | |

| [Family Structure = 2] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [family structure = 1] | −1.661 | 1.384 | 1.441 | 1 | 0.230 | −4.373 | 1.051 | |

| [family structure = 2] | −2.731 | 1.253 | 4.755 | 1 | 0.029 | −5.187 | −0.276 | |

| [family structure = 3] | −1.516 | 1.766 | 0.738 | 1 | 0.390 | −4.977 | 1.944 | |

| [family structure = 4] | −4.968 | 2.174 | 5.221 | 1 | 0.022 | −9.230 | −0.706 | |

| [family structure = 5] | −2.288 | 1.244 | 3.382 | 1 | 0.066 | −4.727 | 0.150 | |

| [family structure = 6] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Hukou Status = 1] | 1.763 | 1.303 | 1.830 | 1 | 0.176 | −0.791 | 4.318 | |

| [Hukou Status = 2] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Length of Living = 2] | 0.294 | 1.624 | 0.033 | 1 | 0.857 | −2.889 | 3.476 | |

| [Length of Living = 3] | 0.026 | 1.183 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.982 | −2.291 | 2.344 | |

| [Length of Living = 4] | 0.128 | 0.641 | 0.040 | 1 | 0.842 | −1.129 | 1.384 | |

| [Length of Living = 5] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| [Personal Monthly Income = 1] | −0.976 | 9.188 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.915 | −18.984 | 17.031 | |

| [Personal Monthly Income = 2] | −0.300 | 9.184 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.974 | −18.301 | 17.700 | |

| [Personal Monthly Income = 3] | 0.718 | 9.203 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.938 | −17.319 | 18.755 | |

| [Personal Monthly Income = 4] | 0 a | . | . | 0 | . | . | . | |

| Model | −2 Log Likelihood | Chi-Square | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis | 723.850 | |||

| General | 579.806 b | 144.044 c | 315 | 1.000 |

References

- Rashid, S.T.; Ngah, N.B.; Eluwa, S.E. Neighbourhood choice factors and residents satisfaction in old and new neighbourhoods of Slemani city, Kurdistan-Iraq. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 3, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Asiyanbola, R.; Raji, B.; Shaibu, G. Urban liveability in Nigeria: A pilot study of Ago Iwoye and Ijebu Igbo, Ogun state. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2012, B1, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Iyanda, S.A.; Mohit, A. Measuring the dimension and attributes of liveability of low-income communities in Nigeria. J. Malays. Inst. Plan. 2016, 14, 383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.; Converse, P.; Rosders, W. The quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations and Satisfactions; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rohe, W.M. From local to global: One hundred years of neighborhood planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uittenbroek, C.J.; Mees, H.L.; Hegger, D.L.; Driessen, P.P. The design of public participation: Who participates, when and how? Insights in climate adaptation planning from the Netherlands. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 2529–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vos, J.; Van Acker, V.; Witlox, F. Urban sprawl: Neighbourhood dissatisfaction and urban preferences. Some evidence from Flanders. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hur, M.; Morrow-Jones, H. Factors that influence residents’ satisfaction with neighborhoods. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, Z. Residential satisfaction of migrants in Wenzhou, an ‘ordinary city’ of China. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, D. Geography of urban life satisfaction: An empirical study of Beijing. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, B. Residential satisfaction in traditional and redeveloped inner city neighborhood: A tale of two neighborhoods in Beijing. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, K.; Handy, S.; Mokhtarian, P. Neighborhood satisfaction in suburban versus traditional environments: An evaluation of contributing characteristics in eight California neighborhoods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.; Dang, Y. Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities 2018, 79, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Cao, X.Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Dong, Y. Examining pedestrian satisfaction in gated and open communities: An integration of gradient boosting decision trees and impact-asymmetry analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 185, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, X. Using the Three-Factor Method to Identify Improvement Priorities for Express and Local Bus Services in the Twin Cities. Minnesota. 2017, 17, 02464. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Z.H.; Huang, J.Z.; Zhou, Y. Toward liveable neighbourhoods: Prioritizing the improvement of neigh bourhood amenities through people-oriented planning in Wuhan. In Proceedings of the 57th ISOCARP World Planning Congress, Doha, Qatar, 8–11 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Lopez, S., Snyder, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mohit, M.A.; Ali, M.S. Neighbourhood satisfaction and QOUL in middle-income housing in Kuala Lumpur City, Malaysia. Plan. Malays. 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, R.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Does compact urban forms relate to good quality of life in high density cities of India? Case Kolkata. Cities 2015, 48, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawwarah, N.; Kari, F.; Mohd Satar, N.; Aziz, W. The Role of Neighbourhood Satisfaction in Mediating Social-Physical Attributes and Urban Quality of Life in Malaysia. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2019, 8, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Geetha, V.; Sahu, S.K.; Susila, C. Assess Quality of Life (QOL) and Glycemic Level among Type 2 Diabetic Patients in Global Hospital and Research Centre and its Units, Sirohi, Rajasthan. Asian J. Nurs. Educ. Res. 2017, 7, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwunmi, A.O.; Akinjare, O.A.; Izobo-Martins, O.O. User’s satisfaction with residential facilities in Nigerian private universities: A study of covenant university. Transnatl. J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Ding, K.L.; Cao, X.Y.; Wu, X.Y. The Review of Research Methods on Neighbourhood Satisfaction and Influencing Factors. Urban Dev. Stud. 2018, 255, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities 2017, 60, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Qin, B. Exploring the link between neighbourhood environment and mental wellbeing: A case study in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y. Relationship between Physical Environment Satisfaction, Neighborhood Satisfaction, and Quality of Life in Gyeonggi, Korea. Land. 2021, 10, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E.O.; Opoko, P.A.; Aduwo, E.B. Satisfaction with neighbourhood environments in public housing: Evidence from Ogun State, Nigeria. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 130, 733–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic, J.; Prebezac, D. Accounting for dynamics in attribute-importance and for competitor performance to enhance reliability of BPNN-based importance–performance analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 5144–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Renzl, B. Assessing asymmetric effects in the formation of employee satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, X.; Huting, J. Using the three-factor theory to identify improvement priorities for express and local bus services: An application of regression with dummy variables in the Twin Cities. Transp. Res. Part A 2018, 113, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive quality and must-be-quality. Hinshitsu 1984, 14, e147–e156. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, R.D. How service marketers can identify value-enhancing service elements. J. Serv. Mark. 1988, 2, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R. The determinants of service quality: Satisfiers and dissatisfiers. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1995, 6, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matzler, K.; Sauerwein, S. The factor structure of customer satisfaction: An empirical test of the importance grid and the penalty-reward-contrast analysis. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2002, 13, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.B.; Cao, X.Y.; Huang, X.Y.; Cao, X.S. Applying the IPA–Kano model to examine environmental correlates of residential satisfaction: A case study of Xi’an. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandez-Portero, C.; Alarcon, D.; Padura, A. Dwelling conditions and life satisfaction of older people through residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Y. Examining Built Environmental Correlates of Neighborhood Satisfaction: A Focus on Analysis Approaches. J. Plan. Lit. 2018, 33, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marans, R.W.; Rodgers, W. Toward an understanding of community satisfaction. Metrop. Am. Contemp. Perspect. 1975, 1, 299–352. [Google Scholar]

- Low, C.-T.; Stimson, R.; Chen, S.; Cerin, E.; Wong, P.P.-Y.; Lai, P.-C. Personal and neighbourhood indicators of quality of urban life: A case study of Hong Kong. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 136, 751–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. City profile: Wuhan 2004–2020. Cities 2022, 123, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Breitung, W.; Li, S.M. The changing meaning of neighbourhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2439–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrlik, J.; Higgins, C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H. Social needs of the elderly and active aging in public open spaces in urban renewal. Cities 2016, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Z.; Ma, Y.X.; Hu, G.Y.; Zhu, S.H. Research on the Construction of the Community Living Circle System for the Aged under the Perspective of Collaborative Creation. Urban Archit. 2020, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.T.; Chen, W.X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L.; Yao, S. Study on age-friendly communities against the background of aging society: A case study of 4 communities in Nanjing City. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2020, 37, 424–431. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Category | Specific Amenities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Administrative and Management | Neighbourhood Civil Centres, Service Stations, Offices of Property Owners Committees, Police Stations, Property Management Offices |

| 2 | Education | Middle Schools, Elementary Schools, Kindergartens, Other Training Institutes |

| 3 | Healthcare | Neighbourhood Hospitals, Clinics, Healthcare Stations, Rehabilitation Centres, Pharmacies |

| 4 | Service and Business | Convenience Stores, Fresh Markets, Dining Halls, Elderly Care Centres, Grocery Stores, Bank and ATMs, Delivery Points, Laundries, Bookstores |

| 5 | Civic and Transportation | Public Toilets, Elevators and Lifts, Garbage Collection Points, Parking Lots, Transportation Stations, Metro Stations, Shared Bicycle Points |

| 6 | Public, Cultural, and Sports | Outdoor Fitness Areas, Fitness Centres, Chess Rooms, Ball Courts and Game Rooms, Elderly Activity Rooms, Neighbourhood Parks or Outside Sitting Areas, Reading Rooms |

| Category | Group | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 2342 | 45.9 |

| Female | 2758 | 54.1 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 541 | 10.6 |

| 26–35 | 1394 | 27.3 | |

| 36–45 | 1186 | 23.3 | |

| 46–60 | 1188 | 23.3 | |

| 60 above | 791 | 15.5 | |

| Education | Lower than primary school | 1 | 0.0 |

| Elementary school | 84 | 1.6 | |

| Secondary school | 2468 | 48.4 | |

| College or higher diploma | 2481 | 48.6 | |

| Postgraduate | 66 | 1.3 | |

| Property Rights of the Occupant | Property owner | 4592 | 90.0 |

| Tenant | 508 | 10.0 | |

| Family Structure | Living alone | 146 | 2.9 |

| Couple only | 915 | 17.9 | |

| Nuclear family | 2361 | 46.3 | |

| Living with parents | 632 | 12.4 | |

| Extended family consisting of three generations | 720 | 14.1 | |

| Other | 326 | 6.4 | |

| Hukou Status | Local hukou | 4477 | 87.8 |

| Nonlocal hukou | 623 | 12.2 | |

| Length of Living | Less than one year | 46 | 0.9 |

| One to three years | 611 | 12.0 | |

| Four to six years | 1325 | 26.0 | |

| Seven to ten years | 832 | 16.3 | |

| Longer than ten years | 2286 | 44.8 | |

| Occupation | Civil servant | 130 | 2.5 |

| Public institution professional | 693 | 13.6 | |

| Private company employee | 1280 | 25.1 | |

| Worker | 355 | 7.0 | |

| Self-employed entrepreneur | 397 | 7.8 | |

| Student | 108 | 2.1 | |

| Freelancer | 276 | 5.4 | |

| Other | 667 | 13.1 | |

| Personal Monthly Income | 3000 RMB and below | 730 | 14.3 |

| 3000–5000 RMB | 2442 | 47.9 | |

| 5001–8000 RMB | 1516 | 29.7 | |

| 8001–10,000 RMB | 339 | 6.6 | |

| 10,000 RMB and above | 73 | 1.4 | |

| Total | 5100 | ||

| Mean value of overall satisfaction with neighbourhood life | 3.44 | 56.58% of the respondents feel satisfied or highly satisfied | |

| Order | Elderly Group (60 Years Old or Above) | Young and Middle-Age Group (From 18 to 59 Years Old) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The ranking of the percentage of respondents who selected the amenity as frequently used ones. | 1 | Fresh Markets | 90.3% | Supermarkets | 85.5% |

| 2 | Supermarkets | 79.1% | Fresh Markets | 79.6% | |

| 3 | Restaurants | 56.3% | Restaurants | 74.6% | |

| 4 | Bus Stations | 48.4% | Convenience Stores | 65.8% | |

| 5 | Community Outside Sitting Areas | 48.2% | Delivery and Pick-up Stations | 60.4% | |

| 6 | Pharmacies | 46.1% | Bus Stations | 59.2% | |

| 7 | Convenience Stores | 42.6% | Subway Stations | 50.0% | |

| The ranking of the amenities to be urgently improved (the percentage of respondents who thought the amenity should be urgently improved). | 1 | Community Outside Sitting Areas | 30.0% | Community Outside Sitting Areas | 25.5% |

| 2 | Fitness Areas | 29.3% | Parking Lots | 23.4% | |

| 3 | Elderly Activity Centres | 24.9% | Fitness Areas | 20.8% | |

| 4 | Public Toilets | 19.8% | Fresh Markets | 16.0% | |

| 5 | Parking Lots | 18.7% | Public Toilets | 10.7% | |

| 6 | Fresh Markets | 13.3% | Garbage Collection Points | 10.6% | |

| 7 | Community Hospitals | 11.5% | Property Management Centres | 9.9% | |

| N | Mean Value | |

|---|---|---|

| 482 | 3.88 |

| 482 | 3.74 |

| 482 | 3.72 |

| 482 | 3.71 |

| 482 | 3.70 |

| 482 | 3.67 |

| 482 | 3.62 |

| 482 | 3.60 |

| 482 | 3.58 |

| 482 | 3.55 |

| 482 | 3.49 |

| 482 | 3.42 |

| 482 | 3.34 |

| 482 | 3.25 |

| 482 | 3.17 |

| 482 | 3.11 |

| 482 | 3.05 |

| 482 | 3.02 |

| 482 | 2.94 |

| 482 | 2.92 |

| 482 | 2.92 |

| 482 | 2.79 |

| 482 | 2.64 |

| Good Performance | Moderate Performance | Poor Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exciting Factors | Convenience Stores | Fresh Markets, Bank Branches, Kindergartens, Public Toilets, Neighbourhood Service Centre | None |

| Important Performance Factors | Community Hospitals, Delivery and Pick Up Stations, Bus Stations Pharmacies | Privately-Owned Education and Training Centres, Chess Rooms | Property Management Centres, Garbage Collection Points, Neighbourhood Squares, Parking Lots |

| Basic Factors | Restaurants | Other Administrative Facilities, Service Stations | Reading Rooms, Elderly Service Stations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Kang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Prioritizing Neighbourhood Amenities to Enhance Neighbourhood Satisfaction: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043528

Zhang Q, Zheng Z, Kang D, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X. Prioritizing Neighbourhood Amenities to Enhance Neighbourhood Satisfaction: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043528

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qi, Zhenhua Zheng, Dezhi Kang, Ying Zhou, Yifeng Zhang, and Xu Zhang. 2023. "Prioritizing Neighbourhood Amenities to Enhance Neighbourhood Satisfaction: A Case Study in Wuhan, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043528