Effectiveness of Operation K9 Assistance Dogs on Suicidality in Australian Veterans with PTSD: A 12-Month Mixed-Methods Follow-Up Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Operation K9 Program

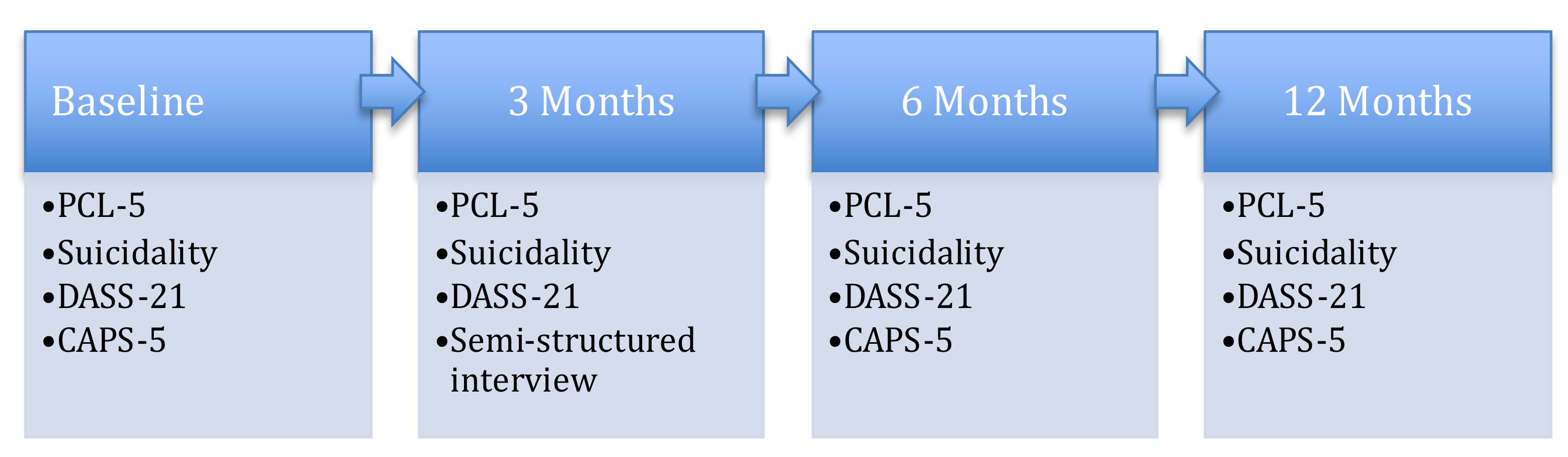

2.3. Design

2.4. Ethics Approval

2.5. Materials and Measures

2.5.1. Self-Report Questionnaire

2.5.2. Clinical Interview

2.5.3. Semi-Structured Qualitative Interview

2.5.4. Procedure

2.5.5. Data Analysis

Research Question 1

Research Question 2

3. Results

3.1. Self-Report Questionnaire

3.1.1. Suicidality

3.1.2. PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety

3.2. Clinician-Diagnosed PTSD (CAPS-5)

3.3. Semi-Structured Qualitative Interview

3.3.1. Life Changer

‘See I didn’t even think it was possible for me to ever, ever improve. I thought this was going to be my lifestyle for the rest of my life, but you know this has just absolutely proven me wrong, it’s turned me right around 180 degrees’.(Veteran #12)

‘You just sort of look at (dog) and you think, well, you know, at least she’s worth living for and she’s there … it sort of reminds you constantly, you know, when you’re all by yourself, there’s always someone there.’(Veteran #6)

and ‘I need to stay alive now otherwise, (dog) would miss me … who would look after (dog), he gives me that right to live again’ (Veteran #12). For many veterans their assistance dog had given them a sense of purpose. One said their dog gave them ‘a reason to be’ (Veteran #2), while another ‘it gives me a reason and purpose now, so I’ve got to stay well and fit enough now to look after him, so he’s now my family’(Veteran #12).

‘He calms me and he knows, he really does know when you’re having a bad day or a problem... he just lays and puts his head on my foot and it is the most calming, relaxing feeling and it’s a confidence thing you know, it just makes me feel good all the time’.(Veteran #12)

3.3.2. Constant Companion

3.3.3. Social Engagement

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, K.; Dipnall, J.; Van Hooff, M.; Lawrence-Wood, E.; Searle, A.; AO, A.M. Identifying clusters of health symptoms in deployed military personnel and their relationship with probable PTSD. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 127, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hooff, M.; Lawrence-Wood, E.; Hodson, S. Mental Health Prevalence, Mental Health and Wellbeing Transition Study; The Department of Defence and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nock, M.K.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.; Kessler, R.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Beautrais, A.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.; Bruffaerts, R.; de Girolamo, G.; et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ursano, R.J.; Heeringa, S.G.; Stein, M.B.; Jain, S.; Raman, R.; Sun, X.; Chiu, W.T.; Colpe, L.J.; Fullerton, C.S.; Gilman, S.E.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 514–522. [Google Scholar]

- Pompili, M.; Sher, L.; Serafini, G.; Forte, A.; Innamorati, M.; Dominici, G.; Lester, D.; Amore, M.; Girardi, P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide risk among veterans: A literature review. J. Ner. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Goldstein, M.B.; Malley, J.C.; Rivers, A.J.; Johnson, D.C.; Southwick, S.M. Risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 123, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Suicide Monitoring of Serving and Ex-Serving Australian Defence Force Personnel: 2020 Update. 2020. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/veterans/national-suicide-monitoring-adf-2020/contents/about-this-report (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Fairweather-Schmidt, K.; Van Hooff, M.; McFarlane, S. Suicidality in the Australian Defence Force: Results from the 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Dataset; Unpublished monthly report; Centre for Traumatic Stress Studies, The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, D.; Pedlar, D.; Adler, A.B.; Bennett, C.; Bryant, R.; Busuttil, W.; Cooper, J.; Creamer, M.C.; Fear, N.T.; Greenberg, N.; et al. Treatment of military-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Challenges, innovations, and the way forward. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phoenix Australia—Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Australian Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. 2013. Available online: https://www.phoenixaustralia.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/03/Phoenix-ASD-PTSD-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Cusack, K.; Jonas, D.E.; Forneris, C.A.; Wines, C.; Sonis, J.; Middleton, J.C.; Feltner, C.; Brownley, K.A.; Olmsted, K.R.; Greenblatt, A.; et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, C.A.; Sarni, S.; Padden, E. Military veterans and canine assistance for post-traumatic stress disorder: A narrative review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 47, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Litz, B.T.; Hoge, C.W.; Marmar, C.R. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: A review of randomized clinical trials. Jama 2015, 314, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, C.W.; Grossman, S.H.; Auchterlonie, J.L.; Riviere, L.A.; Milliken, C.S.; Wilk, J.E. PTSD treatment for soldiers after combat deployment: Low utilization of mental health care and reasons for dropout. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, J.M.; Mondragon, S.; Hundt, N.E.; Beason-Smith, M.; Grady, R.H.; Teng, E.J. Characteristics of US veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assistance Dogs International. ADI Terms and Definitions. 2020. Available online: https://assistancedogsinternational.org/resources/adi-terms-definitions/ (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- O’Haire, M.E.; Rodriguez, K.E. Preliminary efficacy of service dogs as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military members and veterans. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Society for the Blind. Operation K9 Fact Sheet. 2019. Available online: https://www.rsb.org.au/sites/default/files/Operation%20K9%20Flyer_2019.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Van Houtert, E.A.; Endenburg, N.; Wijnker, J.J.; Rodenburg, B.; Vermetten, E. The study of service dogs for veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A scoping literature review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9 (Suppl. S3), 1503523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowe, T.K.; Sánchez, V.; Howard, A.; Western, B.; Barger, S. Veterans transitioning from isolation to integration: A look at veteran/service dog partnerships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2953–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloep, M.L.; Hunter, R.H.; Kertz, S.J. Examining the effects of a novel training program and use of psychiatric service dogs for military-related PTSD and associated symptoms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2017, 87, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, C.; Belleville, G.; Gagnon, D.H.; Dumont, F.; Auger, E.; Lavoie, V.; Besemann, M.; Champagne, N.; Lessart, G. Effectiveness of Service Dogs for Veterans with PTSD: Preliminary Outcomes. In Harnessing the Power of Technology to Improve Lives; Cudd, P., Ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth, J.D.; Scotland-Coogan, D.; Wharton, T. Service dog training programs for veterans with PTSD: Results of a pilot controlled study. Soc. Work. Heal. Care 2019, 58, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, C.A.; Morales, K.A. Military veterans and service dogs: A qualitative inquiry using interpretive phenomenological analysis. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, C.A.; Rice, M.J.; Sarni, S.; Lofaro, C.; Niitsu, K.; McHenry-Edrington, M.; Blanchard, K. Protective Factors for Suicide: A Multi-Tiered Veteran-Driven Community Engagement Project. J. Vet. Stud. 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.; Hamilton, A.L. Exploring the influence of service dogs on participation in daily occupations by veterans with PTSD: A pilot study. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2019, 66, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarborough, B.J.H.; Stumbo, S.P.; Yarborough, M.T.; Owen-Smith, A.; Green, C.A. Benefits and challenges of using service dogs for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2018, 41, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Kimerling, R.; Brown, P.; Chrestman, K.; Levin, K. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. 2007. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-survey-mental-health-and-wellbeing-summary-results/latest-release (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Wolfe, J.; Kimerling, R.; Brown, P.; Chrestman, K.; Levin, K. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5); U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P.; Weathers, F.W.; Gallagher, M.W.; Rodriguez, P.; Schnurr, P.P.; Keane, T.M. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, J.; Kimerling, R.; Brown, P.; Chrestman, K.; Levin, K. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5: Past Month Version; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2016, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE: Great Britain, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan, A.; Laird, N.M.; Slasor, P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Stat. Med. 1997, 16, 2349–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Caracelli, V.J.; Graham, W.F. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1989, 11, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, J.P.; Gilbert, D.G. Effects of repeated administration of the Beck Depression Inventory and other measures of negative mood states. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 24, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, C.M.; Schnurr, P.P.; Resick, P.A.; Friedman, M.J.; Young-Xu, Y.; Stevens, S.P. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; World Health Organization: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1986. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Quantitative Data n = 16 | Qualitative Data n = 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 14 | 87.5 | 10 | 83 |

| Female | 2 | 12.5 | 2 | 17 |

| Age | ||||

| Range 34–74 | M = 50.88 (SD = 12.88) | M = 52.85 (SD = 13.3) | ||

| Service | ||||

| Navy | 2 | 12.5 | 2 | 17 |

| Army | 14 | 75 | 9 | 75 |

| Air Force | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 8 |

| Exp β | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidality | Intercept | 1.286 | [0.48, 3.45] | 0.618 |

| Time | ||||

| Baseline * | (REF) | |||

| 3 months | 0.467 | [0.21, 1.04] | 0.061 | |

| 6 months | 0.467 | [0.16, 1.37] | 0.164 | |

| 12 months | 0.605 | [0.18, 2.00] | 0.409 |

| Measure | Baseline M (SD) | 3 Months M (SD) | 6 Months M (SD) | 12 Months M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-5 (/80) | 67.69 (16.08) | 60.19 (18.86) | 54.44 (16.52) | 51.56 (18.01) |

| DASS-21 | ||||

| Depression (/42) | 21.25 (11.84) | 16.88 (9.32) | 14.13 (10.31) | 15.75 (11.59) |

| Anxiety (/42) | 20 (10.30) | 12.50 (7.36) | 12.25 (8.91) | 10.50 (9.14) |

| Time | Mean Difference | 95% CI | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-5 Baseline * | |||

| 3 months | 7.32 ** | [2.85, 11.78] | 0.43 |

| 6 months | 13.07 *** | [8.60, 17.53] | 0.81 |

| 12 months | 15.94 *** | [11.48, 20.40] | 0.94 |

| Depression Subscale | |||

| Baseline * | |||

| 3 months | 4.38** | [0.26, 8.49] | 0.41 |

| 6 months | 7.13** | [3.01, 11.24] | 0.64 |

| 12 months | 5.50** | [1.39, 9.61] | 0.47 |

| Anxiety Subscale | |||

| Baseline * | |||

| 3 months | 7.5*** | [3.98, 11.02] | 0.84 |

| 6 months | 7.75*** | [4.23, 11.27] | 0.8 |

| 12 months | 9.5*** | [5.98, 13.03] | 0.98 |

| Baseline to 3 Months | Baseline to 6 Months | Baseline to 12 Months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Reliable Change | 9 | 56 | 13 | 81 | 14 | 88 |

| Clinical Significance | 7 | 44 | 11 | 69 | 10 | 63 |

| Exp β | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD Case | Intercept | 2.200 | [0.72, 6.73] | 0.167 |

| Time | ||||

| Baseline * | ||||

| 6 months | 0.430 | [0.10, 1.84] | 0.255 | |

| 12 months | 0.207 | [0.07, 0.66] | 0.008 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sherman, M.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Bowen, H.; Iannos, M.; Van Hooff, M. Effectiveness of Operation K9 Assistance Dogs on Suicidality in Australian Veterans with PTSD: A 12-Month Mixed-Methods Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043607

Sherman M, Hutchinson AD, Bowen H, Iannos M, Van Hooff M. Effectiveness of Operation K9 Assistance Dogs on Suicidality in Australian Veterans with PTSD: A 12-Month Mixed-Methods Follow-Up Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043607

Chicago/Turabian StyleSherman, Melissa, Amanda D. Hutchinson, Henry Bowen, Marie Iannos, and Miranda Van Hooff. 2023. "Effectiveness of Operation K9 Assistance Dogs on Suicidality in Australian Veterans with PTSD: A 12-Month Mixed-Methods Follow-Up Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043607

APA StyleSherman, M., Hutchinson, A. D., Bowen, H., Iannos, M., & Van Hooff, M. (2023). Effectiveness of Operation K9 Assistance Dogs on Suicidality in Australian Veterans with PTSD: A 12-Month Mixed-Methods Follow-Up Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043607