Peer Support Activities for Veterans, Serving Members, and Their Families: Results of a Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

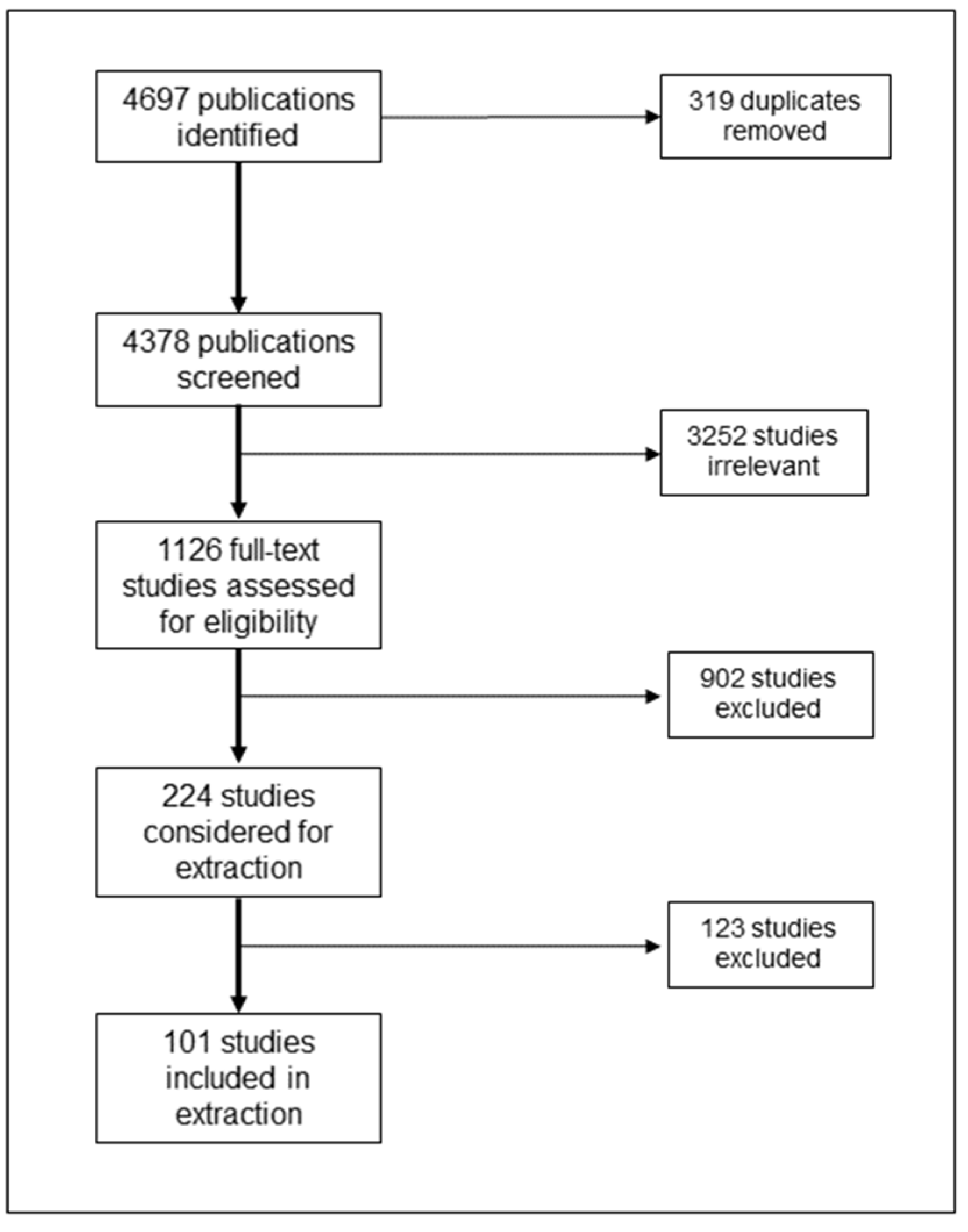

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Research Question

- What are the characteristics of the veterans, serving members, and their families participating in these peer support activities?

- What are the types and characteristics of the peer support activities evaluated in the literature for veterans, serving members, and their families?

- Which domains of well-being are these activities aiming to improve?

- What are the gaps and limitations in the literature on peer support activities for veterans, serving members, and their families?

2.2. Identification of Relevant Publications

2.3. Article Selection

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Collating and Summarizing Results

- Publication characteristics: including year of publication, country, journal, and design of the publication;

- Participant information: including group (veteran, serving member, families), health condition, phase of the life course, and sex and gender;

- Activity information: including name, format, modality, timing, duration and intensity, supervision, cost, reported adverse effects, and measured outcomes;

- Peer information: including main role of peer, integration in a clinical team, training, and category related to remuneration. A ‘yes’ or ‘no’ approach to the training component was used, due to the varied nature of training described in the literature.

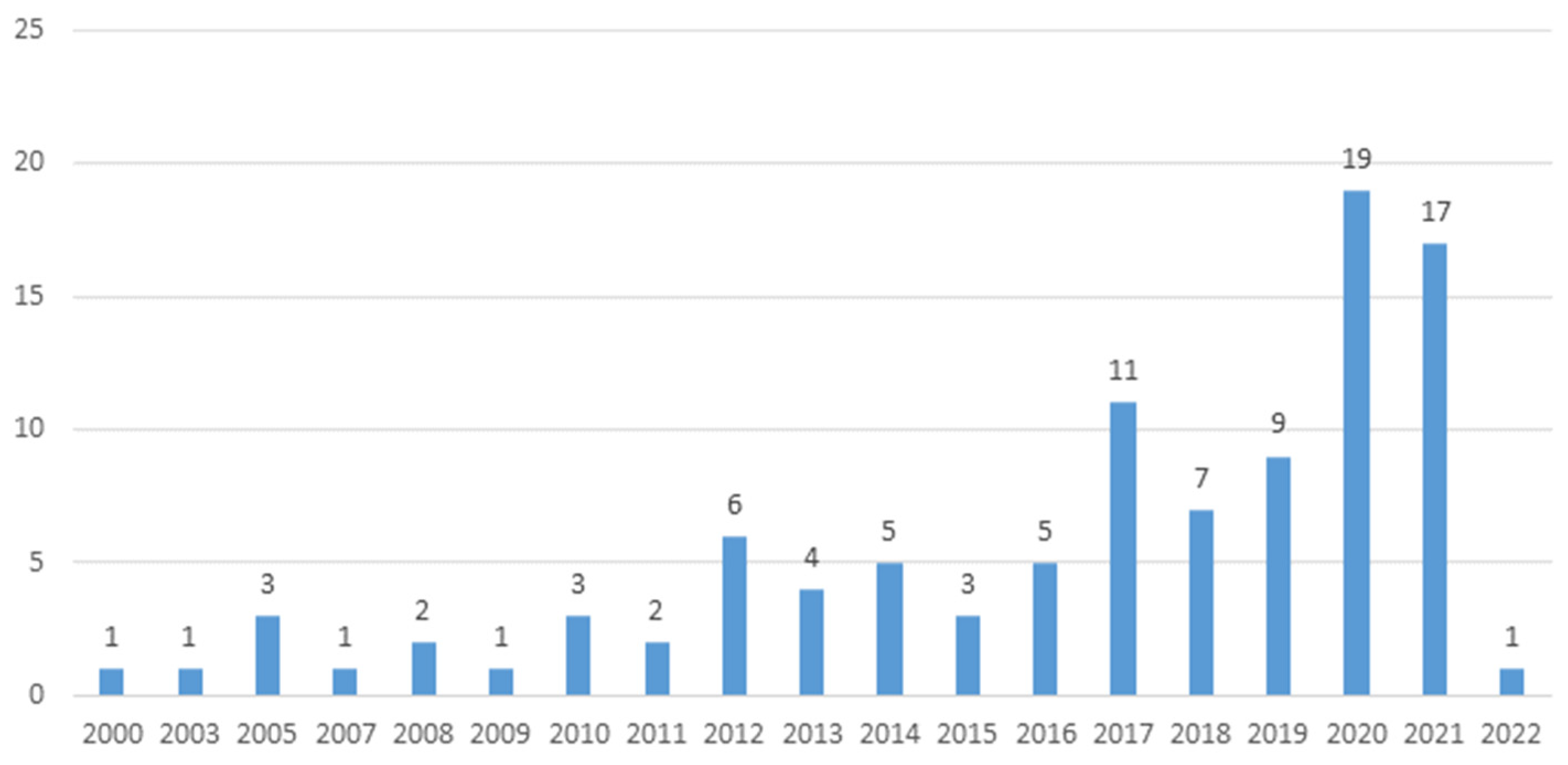

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Activity Characteristics

3.3. Peer Characteristics

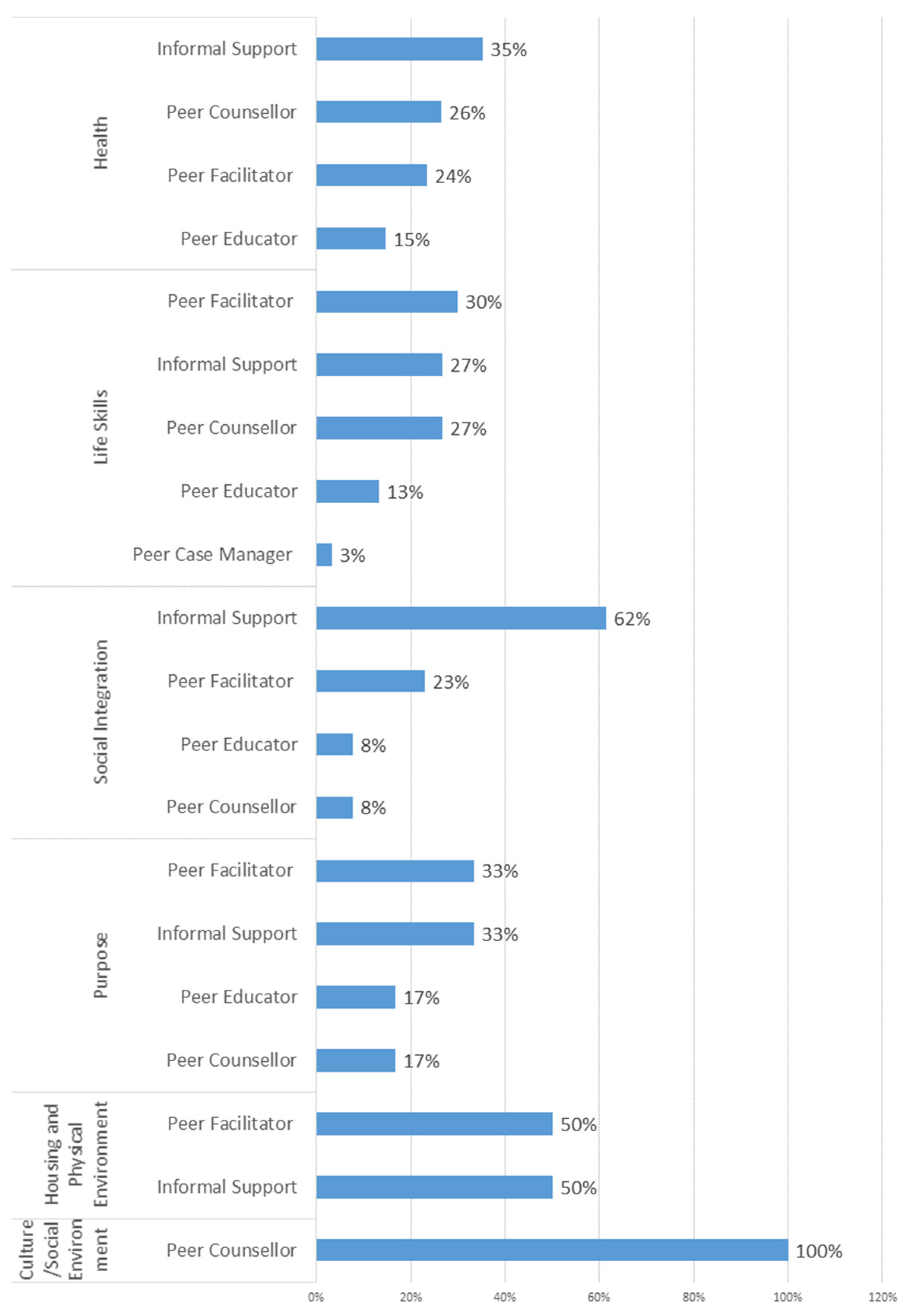

3.4. Veterans’ Well-Being Framework

4. Discussion

4.1. Participant and Activity Characteristics

4.2. Domains of Well-Being

4.3. Gaps and Limitations in the Literature

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Activity Name | Number of Publications |

|---|---|

| Not Named | 24 |

| Vet-to-Vet | 5 |

| Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) | 3 |

| Evaluation of a Peer Coach-Led Intervention to Improve Pain Symptoms (ECLIPSE) | 2 |

| Improving Pain using Peer-Reinforced Self-Management Strategies (IMPPRESS) | 2 |

| Group-intensive peer support (GIPS) model for the Housing and Urban Development-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program | 2 |

| Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT); Homeless-oriented PACT (H-PACT) | 2 |

| Taking Charge of My Life and Health (TCMLH) | 2 |

| Posts Working for Veterans’ Health (POWER) | 2 |

| MOVE!+UP | 2 |

| AMPS (Administering MISSION Vet using Peer Support) | 2 |

| Mentors Offering Maternal Support (MOMS) | 2 |

| Peer Supported Beating the Blues (PS-cCBT) | 2 |

| Homefront | 2 |

| The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Peer Support Program (PSP) | 2 |

| Stand Down: Think Before You Drink + Peer Support | 1 |

| The Military Spouse Online Autism Relocation Readiness (MilSOARR) | 1 |

| Quick Reaction Force | 1 |

| Trojan’s Trek (TT) Peer Outdoor Support Therapy (POST) | 1 |

| Living-Well | 1 |

| Buddy-Care | 1 |

| Mentorship for Addictions Problems to Enhance Engagement to Treatment (MAP-Engage) | 1 |

| Veteran Coffee Socials | 1 |

| Mission Strong Booster Session | 1 |

| Shared Medical Appointments | 1 |

| Motivational Coaching to Enhance Mental Health Engagement in Rural Veterans (COACH) | 1 |

| The Artful Grief Studio | 1 |

| MOVE OUT | 1 |

| The Stanford Program (chronic condition self-management [CCSM]) | 1 |

| Care Coordination Home Telehealth (CCHT) | 1 |

| Thinking Forward with Peer Support | 1 |

| VA CONNECT | 1 |

| Next Mission; Women Warriors | 1 |

| Big Brother Program | 1 |

| Caring Cards | 1 |

| Reciprocal Diabetes Peer Support Program (RPS) with Nurse Care Management (NCM) | 1 |

| Operational Stress Injury Social Support (OSISS) Peer Support Network (PSN) | 1 |

| Spark People (SP) | 1 |

| Outdoor Recreational activities | 1 |

| Armed Forces and Veterans’ Breakfast Clubs (AFVBCs) | 1 |

| Depression Intervention, Actively Learning and Understanding With Peers (DIAL-UP) | 1 |

| The Exposure Therapy Peer Support Program | 1 |

| Peer Enhanced Exposure Therapy (PEET) | 1 |

| The Right Turn | 1 |

| The Strong Military Families (SMF) intervention | 1 |

| Vets & Friends | 1 |

| The Wellness Program | 1 |

| Empowering Patients in Chronic Care | 1 |

| AboutFace | 1 |

| Understanding Suicide | 1 |

| Post War: Survive to Thrive Program | 1 |

| VA Student Partnership for Rural Veterans (VSP) | 1 |

| Adapted Maintaining Independence and Sobriety through Systems Integration, Outreach, and Networking-Veterans Edition (MISSION-Vet) | 1 |

| Veteran Supported Education Treatment Manual (VetSEd) | 1 |

| Proactive, Recovery-Oriented Treatment Navigation to Engage Racially Diverse Veterans in Mental Healthcare (PARTNER-MH) | 1 |

| Project The Outreach and Rehabilitation Center for Homeless Veterans (TORCH) Peer Mentor Program | 1 |

| VETS PREVAIL | 1 |

| Peer-delivered Whole Health Coaching | 1 |

| Web MOVE | 1 |

| Peers Enhancing Recovery (PEER) | 1 |

| Citation | Population Group | Peer Role | Measured Domain | Positively Associated Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hall et al. 2020 [38] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Life Skills, Health | Health |

| McDermott 2020 [39] | Veterans | Informal Support | Social Integration | Social Integration |

| Thoits et al. 2000 [40] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration | N/A |

| Geron et al. 2003 [41] | Families | Informal Support | Social Integration, Life Skills | Social Integration |

| Resnick and Rosenheck 2010 [42] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | N/A | N/A |

| Perlman et al. 2010 [43] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration, Life Skills | Health, Social Integration, Life Skills |

| Heisler and Piette 2005 [44] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Purpose, Life Skills | Purpose, Life Skills |

| Weissman et al. 2005 [45] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Housing and Physical Environment, Purpose, Social Integration, Health | Housing and Physical Environment, Purpose |

| Vakharia et al. 2007 [46] | Veterans | Informal Support | Life Skills, Health | Life skills, Health |

| Barber et al. 2008 [47] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Purpose | N/A |

| Resnick and Rosenheck 2008 [48] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Life Skills, Health | Life Skills, Health |

| Greenberg et al. 2011 [49] | Serving Members | Peer Educator | N/A | N/A |

| Tracy et al. 2011 [50] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Life Skills | N/A |

| Long et al. 2012 [51] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health | Health |

| Greenberg et al. 2010 [52] | Serving Members | Peer Educator | Health, Culture/Social Environment | N/A |

| Heisler et al. 2010 [53] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration, Life Skills | Health, Social Integration |

| Eisen et al. 2012 [54] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Purpose, Social Integration, Health | N/A |

| Beattie et al. 2013 [55] | Mix: Veterans and Families | Informal Support | Health, Purpose, Life Skills | Health, Life Skills |

| Gabrielian et al. 2013 [56] | Veterans | Peer Educator | N/A | N/A |

| Mosack et al. 2013 [57] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Health, Life Skills, Social Integration | Health, Life Skills |

| Nichols et al. 2013 [58] | Families | Informal Support | Health, Life Skills, Social Integration | Health, Social Integration |

| Beehler et al. 2014 [59] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Life Skills, Social Integration | Life Skills |

| Mosack et al. 2012 [60] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Life Skills, Health | Health, Life Skills |

| Tsai and Rosenheck 2012 [61] | Veterans | Informal Support | Housing and Physical Environment, Health, Social Integration | Social Integration, Health, Housing and Physical Environment |

| VanVoorhees et al. 2012 [62] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills, Culture/Social Environment | Health, Culture/Social Environment |

| Weis and Ryan 2012 [63] | Families, Serving Members | Peer Facilitator | Life Skills, Social Integration | N/A |

| Holtz et al. 2014 [64] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health | N/A |

| Matthias et al. 2020 [65] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills | N/A |

| Tsai et al. 2014 [66] | Veterans | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Whittle et al. 2014 [67] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Health, Life Skills | N/A |

| Bird 2015 [68] | Mix: Veterans and Serving Members | Peer Facilitator | Health, Purpose, Social Integration, Life Skills | Health, Purpose, Social Integration, Life Skills |

| Chinman et al. 2015 [3] | Veterans | Peer Case Manager | Purpose, Life Skills, Social Integration, Health | Life Skills |

| Matthias et al. 2015 [69] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills, Social Integration | N/A |

| Valenstein et al. 2016 [70] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Purpose | N/A |

| Nelson et al. 2014 [71] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health | Health |

| Cohen et al. 2017 [72] | Veterans | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Fletcher et al. 2017 [73] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Social Integration | Social Integration |

| Vagharseyyedin et al. 2017 [74] | Families | Peer Facilitator | Social Integration, Purpose | Social Integration |

| Weis et al. 2017 [75] | Families, Serving Members | Peer Facilitator | Health, Social Integration, Life Skills | Health |

| Yoon et al. 2017 [76] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Young et al. 2017 [77] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health | Health |

| Chinman et al. 2018 [78] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Health, Social Integration | N/A |

| Cheney et al. 2016 [79] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Ellison et al. 2016 [80] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills | N/A |

| Jain et al. 2016 [81] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration | N/A |

| Matthias et al. 2016 [82] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Ellison et al. 2018 [83] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills | Life Skills |

| Goetter et al. 2018 [84] | Veterans | Peer Case Manager | Life Skills | N/A |

| Gorman et al. 2018 [85] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Social Integration | Social Integration |

| Julian et al. 2018 [86] | Mix: Serving Members and Families | Informal Support | Life Skills | Life Skills |

| Messinger et al. 2018 [87] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Life Skills | N/A |

| Hernandez-Tejada et al. 2017 [88] | Veterans | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Hernandez-Tejada et al. 2017 [89] | Veterans | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Jones et al. 2017 [90] | Serving Members | Peer Counsellor | Health | Health |

| Resnik et al. 2017 [91] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Vagharseyyedin et al. 2018 [92] | Families | Peer Facilitator | Health | Health |

| Hamblen et al. 2019 [93] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health | N/A |

| Haselden et al. 2019 [94] | Families | Peer Facilitator | Health, Social Integration, Life Skills | Health, Social Integration, Life Skills |

| Kumar et al. 2019 [95] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Life Skills, Social Integration | Life Skills, Social Integration |

| Lott et al. 2019 [96] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Life Skills, Social Integration, Health | Life Skills, Social Integration, Health |

| McCarthy et al. 2019 [97] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Social Integration | N/A |

| Possemato et al. 2019 [98] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Health, Purpose | N/A |

| Romaniuk et al. 2019 [99] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Purpose, Health | Purpose, Health |

| VanVoorhees et al. 2019 [100] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Arney et al. 2020 [101] | Veterans | Informal Support | Social Integration, Life Skills, Health | Social Integration, Life Skills, Health |

| Azevedo et al. 2020 [102] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Social Integration, Life Skills | Social Integration, Life Skills |

| Blonigen et al. 2020 [103] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Life Skills, Health | Life Skills |

| Boehm et al. 2020 [104] | Mix: Veterans and Families | Informal Support | Social Integration | Social Integration |

| Eliacin et al. 2020 [105] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Ellison et al. 2020 [106] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Housing | N/A |

| Harris et al. 2020 [107] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Life Skills | Life Skills |

| Hoerster et al. 2020 [108] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Health, Life Skills | Health, Life Skills |

| Matthias et al. 2020 [109] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health | N/A |

| Pfeiffer et al. 2020 [110] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills | Health, Life Skills |

| Johnson et al. 2021 [111] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Life Skills | Life Skills |

| van Reekum and Watt 2019 [112] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration | Health, Social Integration |

| Albertson et al. 2017 [113] | Veterans | Informal Support | Purpose, Health | Purpose, Health |

| DND 2005 [8] | Mix: Veterans and Serving Members | Peer Case Manager | N/A | N/A |

| Yeshua-Katz 2021 [114] | Mix: Veterans and Families | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Turner et al. 2021 [115] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health, Life Skills | Health, Life Skills |

| Strouse et al. 2021 [116] | Families | Informal Support | Social Integration, Purpose | Social Integration, Purpose |

| Seal et al. 2021 [117] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Health, Social Integration | Health, Social Integration |

| Schutt et al. 2021 [118] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Housing | N/A |

| Robustelli et al. 2022 [119] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | N/A | N/A |

| Rajai et al. 2021 [120] | Families | Informal Support | Life Skills, Social integration | Life Skills, Social integration |

| Muralidharan et al. 2021 [121] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | N/A | N/A |

| Gromatsky et al. 2021 [122] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration | Health, Social Integration |

| Kremkow and Finke 2022 [123] | Families | Peer Counsellor | Social Integration, Life Skills | Social Integration, Life Skills |

| Hernandez-Tejada et al. 2021 [124] | Veterans | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Gebhardt et al. 2021 [125] | Veterans | Informal Support | N/A | N/A |

| Ehret et al. 2021 [126] | Mix: Veterans and Serving Members | Informal Support | Social Integration | Social Integration |

| Heisler et al. 2021 [127] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Health | Health |

| Coughlin et al. 2021 [128] | Serving Members | Peer Educator | N/A | N/A |

| Balmer et al. 2020 [129] | Mix: Veterans and Families | Informal Support | Social Integration, Life Skills | Social Integration, Life Skills |

| Abadi et al. 2021 [130] | Veterans | Peer Facilitator | Health, Life Skills | Health, Life Skills |

| Wheeler et al. 2020 [131] | Veterans | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration | Health, Social Integration |

| Villaruz Fisak et al. 2020 [132] | Serving Members | Informal Support | Health, Social Integration | N/A |

| Norman et al. 2020 [133] | Veterans | Informal Support | Social Integration, Life Skills, Health | Social Integration, Life Skills, Health |

| Haselden et al. 2020 [134] | Families | Peer Facilitator | Life Skills | Life Skills |

| Long et al. 2020 [135] | Veterans | Peer Counsellor | Health | N/A |

| Abadi et al. 2021 [136] | Veterans | Peer Educator | Health, Life Skills | Health, Life Skills |

References

- Davidson, L.; Chinman, M.; Kloos, B.; Weingarten, R.; Stayner, D.; Tebes, J.K. Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 6, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchand, R.; Ahluwalia, S.C.; Xenakis, L.; Apaydin, E.; Raaen, L.; Grimm, G. A systematic review of peer-supported interventions for health promotion and disease prevention. Prev. Med. 2017, 101, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinman, M.; Oberman, R.S.; Hanusa, B.H.; Cohen, A.N.; Salyers, M.P.; Twamley, E.W.; Young, A.S. A cluster randomized trial of adding peer specialists to intensive case management teams in the Veterans Health Administration. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhr, D.C.; Salisbury, T.T.; De Silva, M.J.; Atif, N.; van Ginneken, N.; Rahman, A.; Patel, V. Effectiveness of peer-delivered interventions for severe mental illness and depression on clinical and psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Bright, K.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Pike, A.D.; Bremault-Phillips, S. Peers supporting reintegration after occupational stress injuries: A qualitative analysis of a workplace reintegration facilitator training program developed by municipal police for public safety personnel. Police J. 2021, 95, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, C. Benefits and employment and care for peer support staff in the veteran community: A rapid narrative literature review. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 2020, 28, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schwei, R.J.; Hetzel, S.; Kim, K.; Mahoney, J.; DeYoung, K.; Frumer, J.; Lanzafame, R.P.; Madlof, J.; Simpson, A.; Zambrano-Morales, E.; et al. Peer-to-peer support and changes in health and well-being in older adults over time. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of National Defence & Veterans Affairs Canada. Interdepartmental Evaluation of the OSISS Peer Support Network; Department of National Defence & Veterans Affairs Canada: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2005.

- Topping, K.J. Peer Education and Peer Counselling for Health and Well-Being: A Review of Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; MacLean, M.; Roach, M.; Macintosh, S.; Banman, M.; Mabior, J.; Pedlar, D. A Well-Being Construct for Veterans’ Policy, Programming and Research; Research Directorate Technical Report; Research Directorate, Veterans Affairs Canada: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 7 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, K.; Garcia-Garzon, E.; Maguire, Á.; Matz, S.; Huppert, F.A. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, P.; Hand, D.J. New statistics for old?—Measuring the wellbeing of the UK. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2017, 180, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.C. Introduction: The many faces of wellbeing. In Cultures of Wellbeing; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.M.; Vogt, D.; Pedlar, D. Success in life after service: A perspective on conceptualizing the well-being of military Veterans. J. Mil. Veterans’ Health 2022, 7, e20210037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veterans Affairs Canada, Strategic Policy Unit. Monitoring the Well-Being of Veterans: A Veteran Well-Being Surveillance Framework; Veterans Affairs Canada, Strategic Policy Unit: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2017.

- Lloyd-Evans, B.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Harrison, B.; Istead, H.; Brown, E.; Pilling, S.; Johnson, S.; Kendall, T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.M.; Bambara, J.; Turner, A.P. A scoping study of one-to-one peer mentorship interventions and recommendations for application with Veterans with postdeployment syndrome. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2012, 27, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, K. Peer outdoor support therapy (POST) for Australian contemporary veterans: A review of the literature. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 2014, 22, 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, P.N.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D.; Rogers, M.A.; Valenstein, M. Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: A meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassuk, E.L.; Hanson, J.; Greene, R.N.; Richard, M.; Laudet, A. Peer-delivered recovery support services for addictions in the United States: A systematic review. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2016, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, G.J.; Harrison, S.; Caldwell, D.M.; Hickman, M.; Campbell, R. Peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11–21 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodar, K.E.; Carlisle, V.; Tang, P.Y.; Fisher, E.B. Identification and characterization of peer support for cancer prevention and care: A practice review. J. Cancer Educ. 2022, 37, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, C.; Roberts, D. Peer support for people with advanced cancer: A systematically constructed scoping review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 12, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, M.; Gitimoghaddam, M.; McKellin, W.H.; Miller, A.R.; Collet, J.P. Understanding the implications of peer support for families of children with neurodevelopmental and intellectual disabilities: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 719640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aterman, S.; Ghahari, S.; Kessler, D. Characteristics of peer-based interventions for individuals with neurological conditions: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 344–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, A.M.; South, J.; Hulme, C.; Woodall, J.; Vinall-Collier, K.; Raine, G.; Kinsella, K.; Dixey, R.; Harris, L.; Wright, N.M. A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of peer education and peer support in prisons. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webel, A.R.; Okonsky, J.; Trompeta, J.; Holzemer, W.L. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.; Foster, R.; Marks, J.; Morshead, R.; Goldsmith, L.; Barlow, S.; Sin, J.; Gillard, S. The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.J.; Simmons, M.B. A systematic review of the attributes and outcomes of peer work and guidelines for reporting studies of peer interventions. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LGBT Purge Fund: About. Available online: https://lgbtpurgefund.com/about/#the-purge (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Government of Canada. Veterans Affairs Canada: Indigenous Veterans. Available online: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/people-and-stories/indigenous-veterans (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Government of Canada. Veterans Affairs Canada: 1.0 Demographics. Available online: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/about-vac/news-media/facts-figures/1-0#a14 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- MacLean, M.B.; Clow, B.; Ralling, A.; Sweet, J.; Poirier, A.; Buss, J.; Pound, T.; Rodd, B. Veterans in Canada Released Since 1998: A Sex-Disaggregated Profile; Research Technical Report; Veterans Affairs Canada, 24 September 2018. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/acc-vac/V32-400-2018-eng.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Veterans Ombudsman: Peer Support for Veterans Who Have Experienced Military Sexual Trauma; Investigative Report Government of Canada. Available online: https://ombudsman-veterans.gc.ca/en/publications/reports-reviews/Peer-Support-for-Veterans-who-have-Experienced-Military-Sexual-Trauma#1 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Hall, S.; Flower, M.; Rein, L.; Franco, Z. Alcohol use and peer mentorship in veterans. J. Humanist Psychol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J. ‘It’s Like Therapy But More Fun’Armed Forces and Veterans’ Breakfast Clubs: A Study of Their Emergence as Veterans’ Self-Help Communities. Sociol. Res. Online 2021, 26, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A.; Hohmann, A.A.; Harvey, M.R.; Fletcher, B. Similar–other support for men undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geron, Y.; Ginzburg, K.; Solomon, Z. Predictors of bereaved parents’ satisfaction with group support: An Israeli perspective. Death Stud. 2003, 27, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, S.G.; Rosenheck, R.A. Who attends Vet-to-Vet? Predictors of attendance in mental health mutual support. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2010, 33, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, L.M.; Cohen, J.L.; Altiere, M.J.; Brennan, J.A.; Brown, S.R.; Mainka, J.B.; Diroff, C.R. A multidimensional wellness group therapy program for veterans with comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2010, 41, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D. I Help you, and you help me. Diabetes Educ. 2005, 31, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, E.M.; Covell, N.H.; Kushner, M.; Irwin, J.; Essock, S.M. Implementing peer-assisted case management to help homeless veterans with mental illness transition to independent housing. Community Ment. Health J. 2005, 41, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakharia, K.T.; Ali, M.J.; Wang, S.J. Quality-of-life impact of participation in a head and neck cancer support group. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 136, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.A.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Armstrong, M.; Resnick, S.G. Monitoring the dissemination of peer support in the VA Healthcare System. Community Ment. Health J. 2008, 44, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, S.G.; Rosenheck, R.A. Integrating peer-provided services: A quasi-experimental study of recovery orientation, confidence, and empowerment. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, N.; Langston, V.; Iversen, A.C.; Wessely, S. The acceptability of ‘Trauma Risk Management’within the UK armed forces. Occup. Med. 2011, 61, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, K.; Burton, M.; Nich, C.; Rounsaville, B. Utilizing peer mentorship to engage high recidivism substance-abusing patients in treatment. Am. J. Drug Alcohol. Abuse 2011, 37, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.A.; Jahnle, E.C.; Richardson, D.M.; Loewenstein, G.; Volpp, K.G. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, N.; Langston, V.; Everitt, B.; Iversen, A.; Fear, N.T.; Jones, N.; Wessely, S. A cluster randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) in a military population. J. Trauma. Stress 2010, 23, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisler, M.; Vijan, S.; Makki, F.; Piette, J. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, S.V.; Schultz, M.R.; Mueller, L.N.; Degenhart, C.; Clark, J.A.; Resnick, S.G.; Christiansen, C.L.; Armstrong, M.; Bottonari, K.A.; Rosenheck, R.A.; et al. Outcome of a randomized study of a mental health peer education and support group in the VA. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, J.; Battersby, M.W.; Pols, R.G. The acceptability and outcomes of a peer-and health-professional-led Stanford self-management program for Vietnam veterans with alcohol misuse and their partners. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielian, S.; Yuan, A.; Andersen, R.M.; McGuire, J.; Rubenstein, L.; Sapir, N.; Gelberg, L. Chronic disease management for recently homeless veterans: A clinical practice improvement program to apply home telehealth technology to a vulnerable population. Med. Care 2013, 51, S44–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosack, K.E.; Patterson, L.; Brouwer, A.M.; Wendorf, A.R.; Ertl, K.; Eastwood, D.; Morzinski, J.; Fletcher, K.; Whittle, J. Evaluation of a peer-led hypertension intervention for veterans: Impact on peer leaders. Health Educ. Res. 2013, 28, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, L.O.; Martindale-Adams, J.; Graney, M.J.; Zuber, J.; Burns, R. Easing reintegration: Telephone support groups for spouses of returning Iraq and Afghanistan service members. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehler, S.; Clark, J.A.; Eisen, S.V. Participant experiences in peer-and clinician-facilitated mental health recovery groups for veterans. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2014, 37, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosack, K.E.; Wendorf, A.R.; Brouwer, A.M.; Patterson, L.; Ertl, K.; Whittle, J.; Morzinski, J.; Fletcher, K. Veterans service organization engagement in ‘POWER,’a peer-led hypertension intervention. Chronic Illn. 2012, 8, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.; Rosenheck, R.A. Outcomes of a group intensive peer-support model of case management for supported housing. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Voorhees, B.W.; Gollan, J.; Fogel, J. Pilot study of Internet-based early intervention for combat-related mental distress. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2012, 49, 1175–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, K.L.; Ryan, T.W. Mentors offering maternal support: A support intervention for military mothers. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 41, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtz, B.; Krein, S.L.; Bentley, D.R.; Hughes, M.E.; Giardino, N.D.; Richardson, C.R. Comparison of Veteran experiences of low-cost, home-based diet and exercise interventions. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2014, 51, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthias, M.S.; Daggy, J.; Adams, J.; Menen, T.; McCalley, S.; Kukla, M.; McGuire, A.B.; Ofner, S.; Pierce, E.; Kempf, C.; et al. Evaluation of a peer coach-led intervention to improve pain symptoms (ECLIPSE): Rationale, study design, methods, and sample characteristics. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 81, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.; Reddy, N.; Rosenheck, R.A. Client satisfaction with a new group-based model of case management for supported housing services. Eval. Program Plan. 2014, 43, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittle, J.; Schapira, M.M.; Fletcher, K.E.; Hayes, A.; Morzinski, J.; Laud, P.; Eastwood, D.; Ertl, K.; Patterson, L.; Mosack, K.E. A randomized trial of peer-delivered self-management support for hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, K. Research evaluation of an Australian peer outdoor support therapy program for contemporary veterans’ wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health 2015, 44, 46–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, M.S.; McGuire, A.B.; Kukla, M.; Daggy, J.; Myers, L.J.; Bair, M.J. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenstein, M.; Pfeiffer, P.N.; Brandfon, S.; Walters, H.; Ganoczy, D.; Kim, H.M.; Cohen, J.L.; Benn-Burton, W.; Carroll, E.; Henry, J.; et al. Augmenting ongoing depression care with a mutual peer support intervention versus self-help materials alone: A randomized trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, C.B.; Abraham, K.M.; Walters, H.; Pfeiffer, P.N.; Valenstein, M. Integration of peer support and computer-based CBT for veterans with depression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.B.; Parent, M.; Taveira, T.H.; Dev, S.; Wu, W.C. A description of patient and provider experience and clinical outcomes after heart failure shared medical appointment. J. Patient Exp. 2017, 4, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, K.E.; Ertl, K.; Ruffalo, L.; Harris, L.; Whittle, J. Empirically derived lessons learned about what makes peer-led exercise groups flourish. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2017, 11, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagharseyyedin, S.A.; Gholami, M.; Hajihoseini, M.; Esmaeili, A. The effect of peer support groups on family adaptation from the perspective of wives of war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Public Health Nurs. 2017, 34, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, K.L.; Lederman, R.P.; Walker, K.C.; Chan, W. Mentors offering maternal support reduces prenatal, pregnancy-specific anxiety in a sample of military women. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Lo, J.; Gehlert, E.; Johnson, E.E.; O’Toole, T.P. Homeless veterans’ use of peer mentors and effects on costs and utilization in VA clinics. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S.; Cohen, A.N.; Goldberg, R.; Hellemann, G.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Niv, N.; Nowlin-Finch, N.; Oberman, R.; Whelan, F. Improving weight in people with serious mental illness: The effectiveness of computerized services with peer coaches. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinman, M.; McCarthy, S.; Bachrach, R.L.; Mitchell-Miland, C.; Schutt, R.K.; Ellison, M. Investigating the degree of reliable change among persons assigned to receive mental health peer specialist services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, A.M.; Abraham, T.H.; Sullivan, S.; Russell, S.; Swaim, D.; Waliski, A.; Lewis, C.; Hudson, C.; Candler, B.; Hall, S.; et al. Using community advisory boards to build partnerships and develop peer-led services for rural student veterans. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2016, 10, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, M.L.; Schutt, R.K.; Glickman, M.E.; Schultz, M.R.; Chinman, M.; Jensen, K.; Mitchell-Miland, C.; Smelson, D.; Eisen, S. Patterns and predictors of engagement in peer support among homeless veterans with mental health conditions and substance use histories. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2016, 39, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; McLean, C.; Adler, E.P.; Rosen, C.S. Peer support and outcome for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a residential rehabilitation program. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthias, M.S.; Kukla, M.; McGuire, A.B.; Damush, T.M.; Gill, N.; Bair, M.J. Facilitators and barriers to participation in a peer support intervention for veterans with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2016, 32, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, M.L.; Reilly, E.D.; Mueller, L.; Schultz, M.R.; Drebing, C.E. A supported education service pilot for returning veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Serv. 2018, 15, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetter, E.M.; Bui, E.; Weiner, T.P.; Lakin, L.; Furlong, T.; Simon, N.M. Pilot data of a brief veteran peer intervention and its relationship to mental health treatment engagement. Psychol. Serv. 2018, 15, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.A.; Scoglio, A.A.; Smolinsky, J.; Russo, A.; Drebing, C.E. Veteran coffee socials: A community-building strategy for enhancing community reintegration of veterans. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, M.M.; Muzik, M.; Kees, M.; Valenstein, M.; Dexter, C.; Rosenblum, K.L. Intervention effects on reflectivity explain change in positive parenting in military Families with young children. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinger, S.; Bozorghadad, S.; Pasquina, P. Social relationships in rehabilitation and their impact on positive outcomes among amputees with lower limb loss at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Tejada, M.A.; Acierno, R.; Sanchez-Carracedo, D. Addressing dropout from prolonged exposure: Feasibility of involving peers during exposure trials. Mil. Psychol. 2017, 29, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Tejada, M.A.; Hamski, S.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Incorporating peer support during in vivo exposure to reverse dropout from prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Clinical outcomes. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2017, 52, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Burdett, H.; Green, K.; Greenberg, N. Trauma Risk Management (TRiM): Promoting Help Seeking for Mental Health Problems among Combat-Exposed U.K. Military Personnel. Psychiatry. 2017, 80, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, L.; Ekerholm, S.; Johnson, E.E.; Ellison, M.L.; O’Toole, T.P. Which homeless veterans benefit from a peer mentor and how? J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagharseyyedin, S.A.; Zarei, B.; Esmaeili, A.; Gholami, M. The Role of Peer Support Group in Subjective Well-Being of Wives of War Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblen, J.L.; Grubaugh, A.L.; Davidson, T.M.; Borkman, A.L.; Bunnell, B.E.; Ruggiero, K.J. An online peer educational campaign to reduce stigma and improve help seeking in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Telemed. e-Health 2019, 25, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselden, M.; Brister, T.; Robinson, S.; Covell, N.; Pauselli, L.; Dixon, L. Effectiveness of the NAMI homefront program for military and veteran Families: In-person and online benefits. Psychiatr Serv. 2019, 70, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Azevedo, K.J.; Factor, A.; Hailu, E.; Ramirez, J.; Lindley, S.E.; Jain, S. Peer support in an outpatient program for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Translating participant experiences into a recovery model. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, B.D.; Dicks, T.N.; Keddem, S.; Ganetsky, V.S.; Shea, J.A.; Long, J.A. Insights into veterans’ perspectives on a peer support program for glycemic management. Diabetes Educ. 2019, 45, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.; Chinman, M.; Mitchell-Miland, C.; Schutt, R.K.; Zickmund, S.; Ellison, M.L. Peer specialists: Exploring the influence of program structure on their emerging role. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possemato, K.; Johnson, E.M.; Emery, J.B.; Wade, M.; Acosta, M.C.; Marsch, L.A.; Rosenblum, A.; Maisto, S.A. A pilot study comparing peer supported web-based CBT to self-managed web CBT for primary care veterans with PTSD and hazardous alcohol use. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2019, 42, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk, M.; Evans, J.; Kidd, C. Evaluation of the online, peer delivered “Post War: Survive to Thrive Program” for Veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Mil. Veterans Health 2019, 27, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees, E.E.; Resnik, L.; Johnson, E.; O’Toole, T. Posttraumatic stress disorder and interpersonal process in homeless veterans participating in a peer mentoring intervention: Associations with program benefit. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arney, J.B.; Odom, E.; Brown, C.; Jones, L.; Kamdar, N.; Kiefer, L.; Hundt, N.; Gordon, H.S.; Naik, A.D.; Woodard, L.D. The value of peer support for self-management of diabetes among veterans in the empowering patients in chronic care intervention. Diabet. Med. 2020, 37, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, K.J.; Ramirez, J.C.; Kumar, A.; LeFevre, A.; Factor, A.; Hailu, E.; Lindley, S.E.; Jain, S. Rethinking violence prevention in rural and underserved communities: How veteran peer support groups help participants deal with sequelae from violent traumatic experiences. J. Rural Health 2020, 36, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonigen, D.M.; Harris-Olenak, B.; Kuhn, E.; Timko, C.; Humphreys, K.; Smith, J.S.; Dulin, P. Using peers to increase veterans’ engagement in a smartphone application for unhealthy alcohol use: A pilot study of acceptability and utility. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2021, 35, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, L.M.; Drumright, K.; Gervasio, R.; Hill, C.; Reed, N. Implementation of a patient and family-centered intensive care unit peer support program at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. 2020, 32, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliacin, J.; Matthias, M.S.; Burgess, D.J.; Patterson, S.; Damush, T.; Pratt-Chapman, M.; McGovern, M.; Chinman, M.; Talib, T.; O’Connor, C.; et al. Pre-implementation Evaluation of PARTNER-MH: A Mental Healthcare Disparity Intervention for Minority Veterans in the VHA. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2021, 48, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, M.L.; Schutt, R.K.; Yuan, L.H.; Mitchell-Miland, C.; Glickman, M.E.; McCarthy, S.; Smelson, D.; Schultz, M.R.; Chinman, M. Impact of peer specialist services on residential stability and behavioral health status among formerly homeless veterans with cooccurring mental health and substance use conditions. Med. Care 2020, 58, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.I.; Strom, T.Q.; Jain, S.; Doble, T.; Raisl, H.; Hundt, N.; Polusny, M.; Fink, D.M.; Erbes, C. Peer-Enhanced Exposure Therapy (PEET): A Case Study Series. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2020, 27, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerster, K.D.; Tanksley, L.; Simpson, T.; Saelens, B.E.; Unützer, J.; Black, M.; Greene, P.; Sulayman, N.; Reiber, G.; Nelson, K. Development of a tailored behavioral weight loss program for veterans with PTSD (MOVE!+ UP): A mixed-methods uncontrolled iterative pilot study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, M.S.; Daggy, J.; Ofner, S.; McGuire, A.B.; Kukla, M.; Bair, M.J. Exploring peer coaches’ outcomes: Findings from a clinical trial of patients with chronic pain. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, P.N.; Pope, B.; Houck, M.; Benn-Burton, W.; Zivin, K.; Ganoczy, D.; Kim, H.M.; Walters, H.; Emerson, L.; Nelson, C.B.; et al. Effectiveness of peer-supported computer-based CBT for depression among veterans in primary care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.M.; Possemato, K.; Martens, B.K.; Hampton, B.; Wade, M.; Chinman, M.; Maisto, S.A. Goal attainment among veterans with PTSD enrolled in peer-delivered whole health coaching: A multiple baseline design trial. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2022, 15, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Reekum, E.A.; Watt, M.C. A pilot study of interpersonal process group therapy for PTSD in Canadian Veterans. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 2019, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, K.; Best, D.; Pinkey, A.; Murphy, T. “It’s Not Just about Recovery”. The Right Turn Veteran-Specific Recovery Service Evaluation; Final Report; Sheffield Hallam University Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice: Sheffield, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshua-Katz, D. The Role of Communication Affordances in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Facebook and WhatsApp Support Groups. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.D.; Lindsay, R.; Heisler, M. Peer coaching to improve diabetes self-management among low-income Black veteran men: A mixed methods assessment of enrollment and engagement. Ann. Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strouse, S.; Hass-Cohen, N.; Bokoch, R. Benefits of an open art studio to military suicide survivors. Arts Psychother. 2021, 72, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, K.H.; Pyne, J.M.; Manuel, J.K.; Li, Y.; Koenig, C.J.; Zamora, K.A.; Abraham, T.H.; Mesidor, M.M.; Hill, C.; Uddo, M.; et al. Telephone veteran peer coaching for mental health treatment engagement among rural veterans: The importance of secondary outcomes and qualitative data in a randomized controlled trial. J. Rural Health 2021, 37, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutt, R.K.; Schultz, M.; Mitchell-Miland, C.; McCarthy, S.; Chinman, M.; Ellison, M. Explaining Service Use and Residential Stability in Supported Housing: Problems, Preferences, Peers. Med. Care 2021, 59 (Suppl. S2), S117–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, B.L.; Campbell, S.B.; Greene, P.A.; Sayre, G.G.; Sulayman, N.; Hoerster, K.D. Table for two: Perceptions of social support from participants in a weight management intervention for veterans with PTSD and overweight or obesity. Psychol. Serv. 2022, 19, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajai, N.; Lami, B.; Pishgooie, A.H.; Habibi, H.; Alavizerang, F. Evaluating the effect of peer-assisted education on the functioning in family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: A clinical trial study. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2021, 42, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, A.; Peeples, A.D.; Hack, S.M.; Fortuna, K.L.; Klingaman, E.A.; Stahl, N.F.; Phalen, P.; Lucksted, A.; Goldberg, R.W. Peer and non-peer co-facilitation of a health and wellness intervention for adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromatsky, M.; Sullivan, S.R.; Mitchell, E.L.; Spears, A.P.; Edwards, E.R.; Goodman, M. Feasibility and acceptability of VA CONNECT: Caring for our nation’s needs electronically during the COVID-19 transition. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremkow, J.; Finke, E.H. Peer Experiences of Military Spouses with Children with Autism in a Distance Peer Mentoring Program: A Pilot Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Tejada, M.A.; Acierno, R.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Re-engaging Dropouts of Prolonged Exposure for PTSD Delivered via Home-Based Telemedicine or In Person: Satisfaction with Veteran-to-Veteran Support. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 48, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, H.M.; Ammerman, B.A.; Carter, S.P.; Stanley, I.H. Understanding suicide: Development and pilot evaluation of a single-session inpatient psychoeducation group. Psychol. Serv. 2021, 19, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehret, B.C.; Treichler, E.B.; Ehret, P.J.; Chalker, S.A.; Depp, C.A.; Perivoliotis, D. Designed and created for a veteran by a veteran: A pilot study of caring cards for suicide prevention. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2021, 51, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, M.; Burgess, J.; Cass, J.; Chardos, J.F.; Guirguis, A.B.; Strohecker, L.A.; Tremblay, A.S.; Wu, W.C.; Zulman, D. M Evaluating the effectiveness of diabetes Shared Medical Appointments (SMAs) as implemented in five veterans affairs health systems: A multi-site cluster randomized pragmatic trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1648–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, L.N.; Blow, F.C.; Walton, M.; Ignacio, R.V.; Walters, H.; Massey, L.; Barry, K.L.; McCormick, R. Predictors of Booster Engagement Following a Web-Based Brief Intervention for Alcohol Misuse Among National Guard Members: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e29397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, B.R.; Sippola, J.; Beehler, S. Processes and outcomes of a communalization of trauma approach: Vets & Friends community-based support groups. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 2764–2780. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.H.; Barker, A.M.; Rao, S.R.; Orner, M.; Rychener, D.; Bokhour, B.G. Examining the impact of a peer-led group program for veteran engagement and well-being. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27 (Suppl. S1), S-37–S-44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.; Cooper, N.R.; Andrews, L.; Hacker Hughes, J.; Juanchich, M.; Rakow, T.; Orbell, S. Outdoor recreational activity experiences improve psychological wellbeing of military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: Positive findings from a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villaruz Fisak, J.F.; Turner, B.S.; Shepard, K.; Convoy, S.P. Buddy Care, a Peer-to-Peer Intervention: A Pilot Quality Improvement Project to Decrease Occupational Stress Among an Overseas Military Population. Mil. Med. 2020, 185, e1428–e1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.P.; Govindjee, A.; Norman, S.R.; Godoy, M.; Cerrone, K.L.; Kieschnick, D.W.; Kassler, W. Natural language processing tools for assessing progress and outcome of two veteran populations: Cohort study from a novel online intervention for posttraumatic growth. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e17424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haselden, M.; Bloomfield-Clagett, B.; Robinson, S.; Brister, T.; Jankowski, S.E.; Rahim, R.; Cabassa, L.J.; Dixon, L. Qualitative study of NAMI Homefront family support program. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 1391–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.A.; Ganetsky, V.S.; Canamucio, A.; Dicks, T.N.; Heisler, M.; Marcus, S.C. Effect of peer mentors in diabetes self-management vs. usual care on outcomes in US veterans with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020, 3, e2016369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadi, M.; Richard, B.; Shamblen, S.; Drake, C.; Schweinhart, A.; Bokhour, B.; Bauer, R.; Rychener, D. Achieving whole health: A preliminary study of tcmlh, a group-based program promoting self-care and empowerment among veterans. Health Educ. Behav. 2022, 49, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Search Strategy | Results |

|---|---|

| 26,856 |

| 22,342 |

| 2410 |

| 23,893 |

| 1309 |

| 13,483 |

| 12,509 |

| 1365 |

| 1293 |

| 2943 |

| 88,081 |

| 30,660 |

| 8075 |

| 8437 |

| 14,515 |

| 3569 |

| 231,843 |

| 251,323 |

| 1455 |

| 1,405,292 |

| 1455 |

| 1307 |

| Variable | Number of Publications (%) |

|---|---|

| Country of Publication | |

| United States | 85 (84.2) |

| UK | 6 (5.9) |

| Iran | 3 (3.0) |

| Australia | 3 (3.0) |

| Canada | 2 (2.0) |

| Israel | 2 (2.0) |

| Design | |

| Experimental | 32 (31.7) |

| Mixed-methods | 22 (21.8) |

| Quasi-experimental | 22 (21.8) |

| Qualitative | 16 (15.8) |

| Observational | 5 (5.0) |

| Other Publication | 2 (2.0) |

| Case Study | 2 (2.0) |

| Variable | Number of Publications (%) |

|---|---|

| Main Population | |

| Veterans | 77 (76.2) |

| Combination | 10 (9.9) |

| Families | 9 (8.9) |

| Serving members | 5 (5.0) |

| Health Condition | |

| No condition specified | 29 (28.7) |

| Metabolic/Cardiovascular | 15 (14.9) |

| PTSD | 15 (14.9) |

| Non-specified mental health | 11 (10.9) |

| Other mental health | 8 (7.9) |

| Dual diagnosis | 7 (6.9) |

| Substance use disorder | 4 (4.0) |

| Chronic pain | 4 (4.0) |

| Depression | 4 (4.0) |

| Other condition | 3 (3.0) |

| Cancer | 1 (1.0) |

| Sex and Gender | |

| Almost all or all male | 67 (66.3) |

| Majority male | 11 (10.9) |

| Almost all or all female | 9 (8.9) |

| Not reported | 7 (6.9) |

| Both | 5 (5.0) |

| Majority female | 2 (2.0) |

| Variable | Number of Publications (%) |

|---|---|

| Format | |

| Group | 46 (45.5) |

| One-to-one | 45 (44.6) |

| Combination | 8 (7.9) |

| Not reported | 2 (2.0) |

| Modality | |

| In-person | 58 (57.4) |

| Choice | 11 (10.9) |

| Phone | 10 (9.9) |

| Online/Remotely | 10 (9.9) |

| Combination | 10 (9.9) |

| Not reported | 2 (2.0) |

| Timing | |

| Synchronous | 93 (92.1) |

| Asynchronous | 6 (5.9) |

| Combination | 2 (2.0) |

| Peer Role | |

| Informal peer support | 34 (33.7) |

| Peer counsellor | 30 (29.7) |

| Peer facilitator | 20 (19.8) |

| Peer educator | 14 (13.9) |

| Peer case manager | 3 (3.0) |

| Peer Supervision | |

| Yes | 83 (82.2) |

| No mention | 18 (17.8) |

| Peer Part of Clinical Team | |

| No | 65 (64.4) |

| Yes | 35 (34.7) |

| N/A | 1 (1.0) |

| Peer Training | |

| Yes | 73 (72.3) |

| No | 25 (24.8) |

| Not reported | 3 (3.0) |

| Evaluated Domains 1 | |

| Health | 56 (55.4) |

| Life Skills | 44 (43.6) |

| Social integration | 39 (38.6) |

| N/A | 20 (19.8) |

| Employment and meaningful activity/purpose | 13 (12.9) |

| Housing and physical environment | 4 (4.0) |

| Culture/social environment | 2 (2.0) |

| Positively Associated Domains 1 | |

| N/A | 44 (43.6) |

| Health | 34 (33.7) |

| Life skills | 30 (29.7) |

| Social integration | 26 (25.7) |

| Employment and meaningful activity/purpose | 6 (5.9) |

| Housing and physical environment | 2 (2.0) |

| Culture/social environment | 1 (1.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mercier, J.-M.; Hosseiny, F.; Rodrigues, S.; Friio, A.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Shields, D.M.; Dupuis, G. Peer Support Activities for Veterans, Serving Members, and Their Families: Results of a Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043628

Mercier J-M, Hosseiny F, Rodrigues S, Friio A, Brémault-Phillips S, Shields DM, Dupuis G. Peer Support Activities for Veterans, Serving Members, and Their Families: Results of a Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043628

Chicago/Turabian StyleMercier, Jean-Michel, Fardous Hosseiny, Sara Rodrigues, Anthony Friio, Suzette Brémault-Phillips, Duncan M. Shields, and Gabrielle Dupuis. 2023. "Peer Support Activities for Veterans, Serving Members, and Their Families: Results of a Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043628

APA StyleMercier, J.-M., Hosseiny, F., Rodrigues, S., Friio, A., Brémault-Phillips, S., Shields, D. M., & Dupuis, G. (2023). Peer Support Activities for Veterans, Serving Members, and Their Families: Results of a Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043628