A Bibliometric Analysis to Identify Research Trends in Intervention Programs for Smartphone Addiction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the classification of intervention programs for smartphone addiction and the knowledge structure behind them?

- What are the growth trends, quantity, and regional distribution of research studies on intervention programs for smartphone addiction?

- Which are the influential journals, authors, and studies on intervention programs for smartphone addiction?

1.1. Intervention in Smartphone Addiction

1.2. Bibliometric Analysis

1.3. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA)

2. Method

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Target Searching

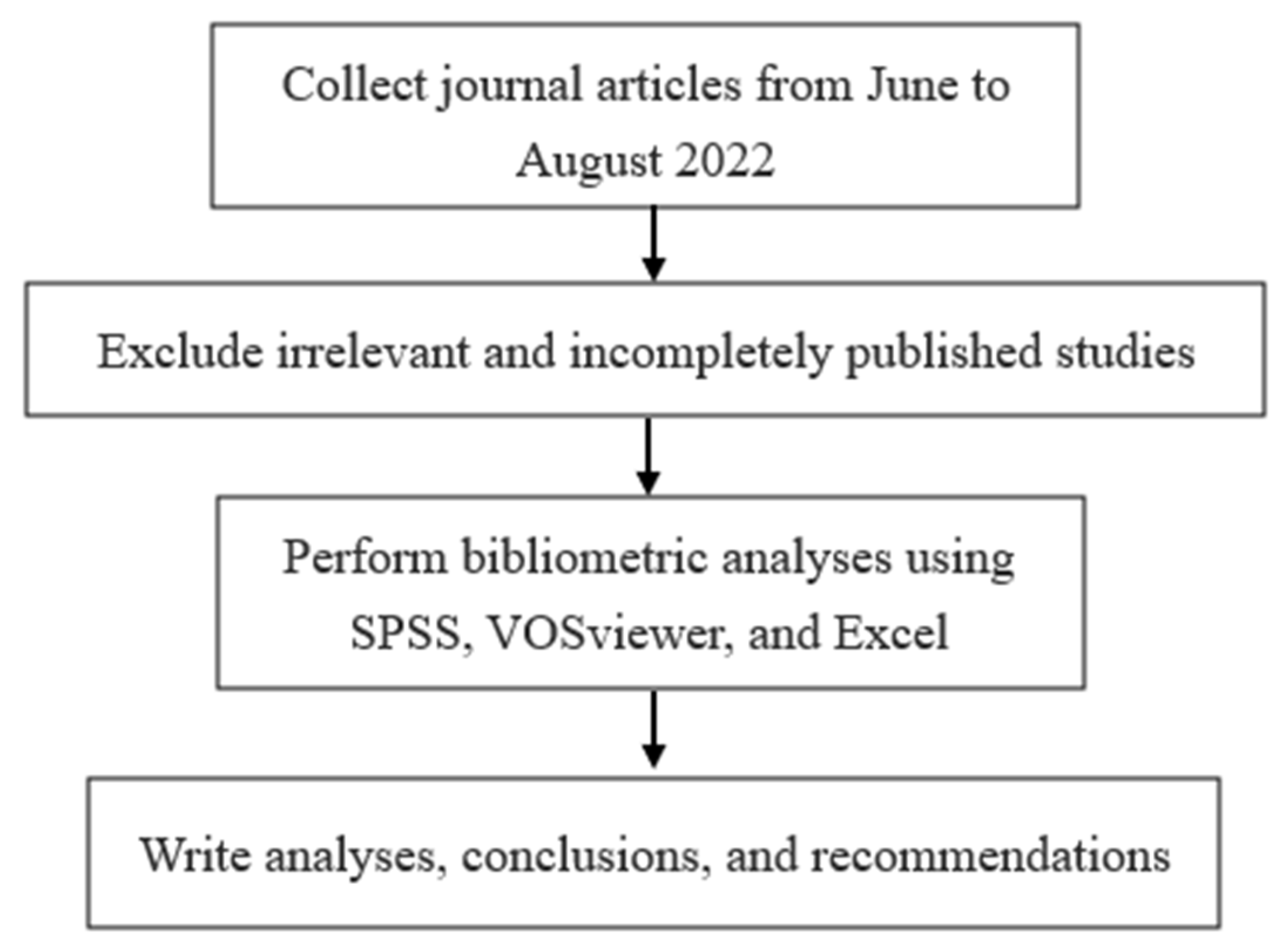

2.3. Research Framework

3. Results

3.1. Scale

3.1.1. Analysis of the Development of Number of Articles on Intervention Programs by Year

3.1.2. Journal Article Citations and Percentages

3.1.3. Research Topic/Abstract Analysis

3.1.4. Research Subject Analysis

3.1.5. Analysis and Definitions of Intervention Program Classifications

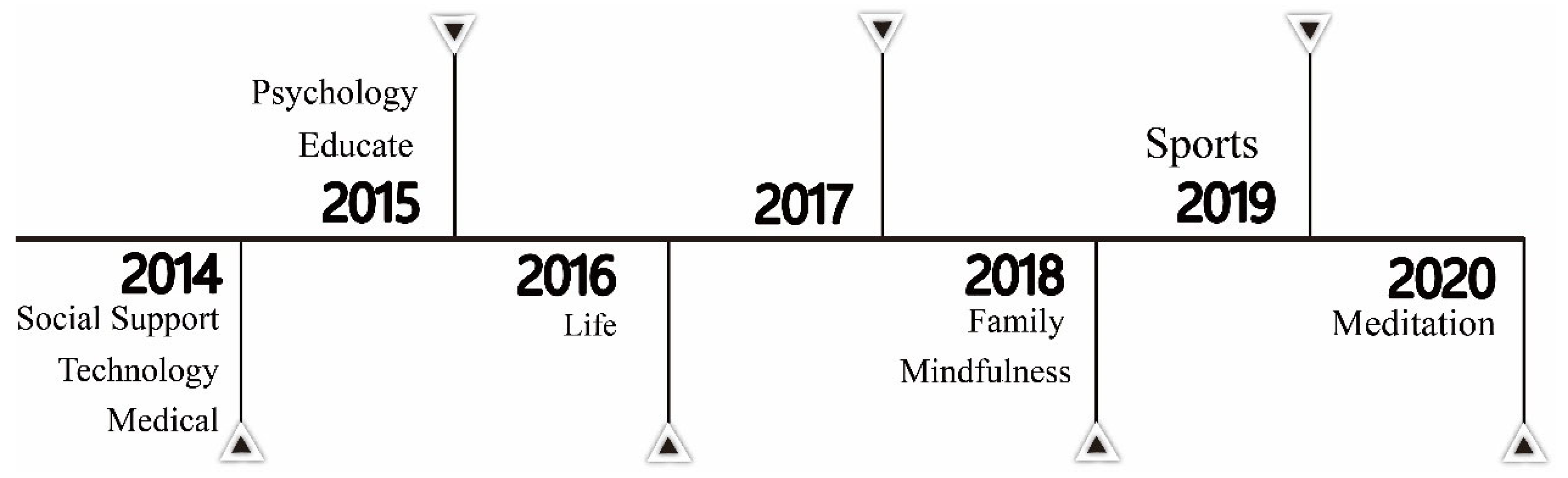

3.2. Time

3.3. Space

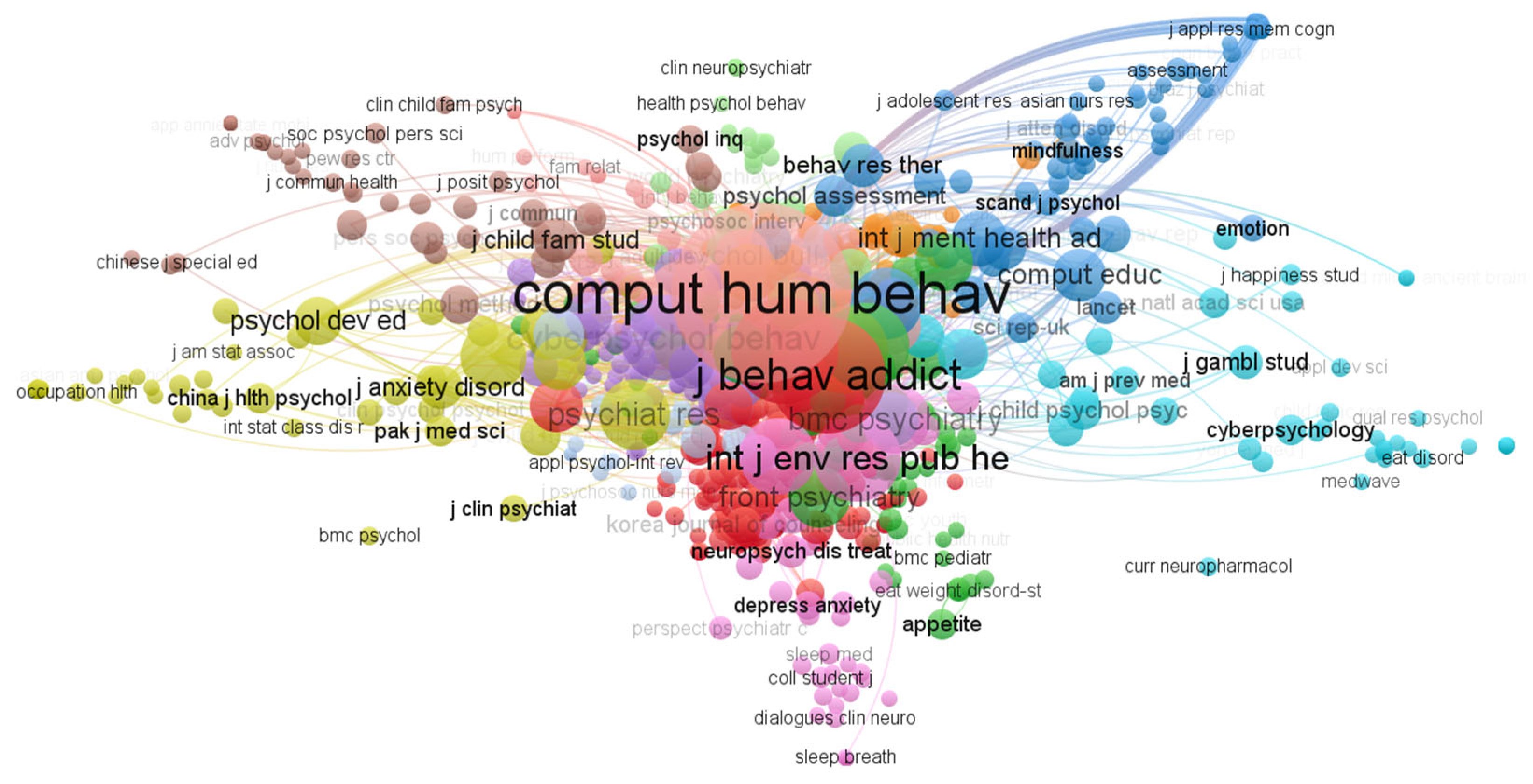

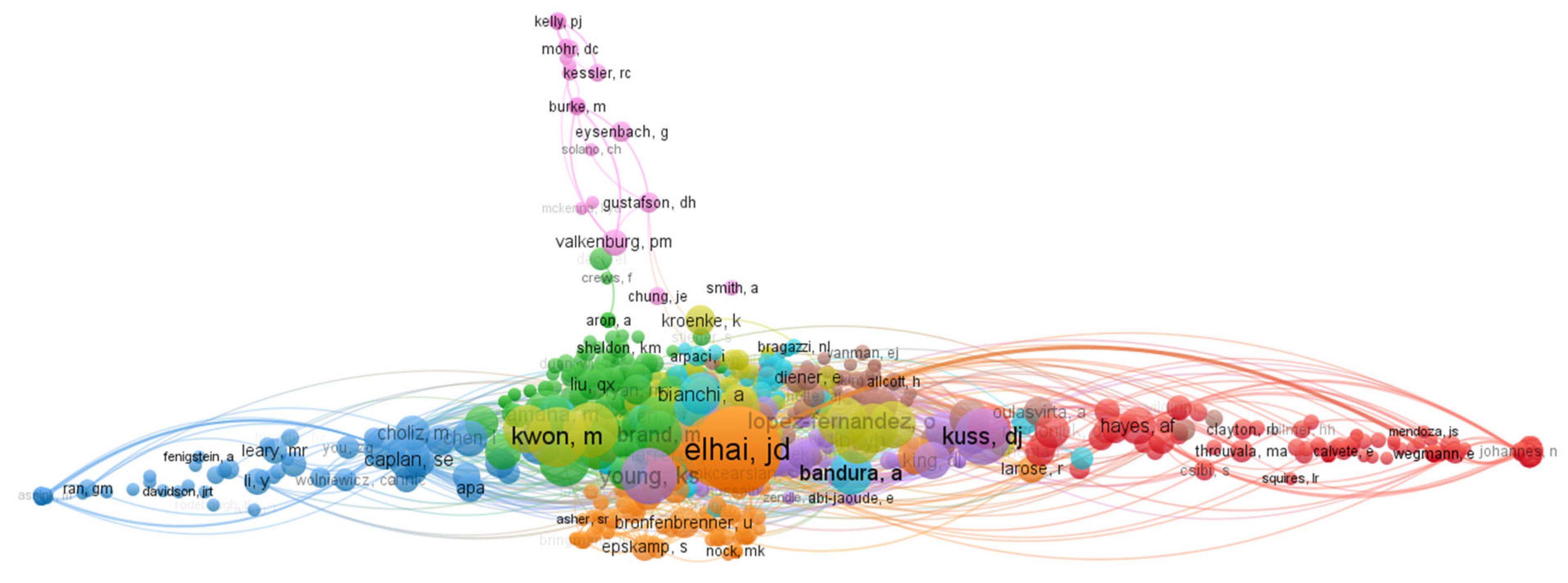

3.4. Composition

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Research Limitations

6. Future Directions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hauser-Ulrich, S.; Künzli, H.; Meier-Peterhans, D.; Kowatsch, T. A smartphone-based health care chatbot to promote self-management of chronic pain (SELMA): Pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e15806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwoye, O.; Reneau, H.; Herron, J.; Alcover, K.C.; McPherson, S.; Roll, J.; McDonell, M.G. Pilot study of an integrated smartphone and breathalyzer contingency management intervention for alcohol use. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masaki, K.; Tateno, H.; Nomura, A.; Muto, T.; Suzuki, S.; Satake, K.; Hida, E.; Fukunaga, K. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation smartphone application with a carbon monoxide checker. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscaro, C.; Giupponi, C. Co-authorship and bibliographic coupling network effects on citations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miralles, I.; Granell, C.; Díaz-Sanahuja, L.; Van Woensel, W.; Bretón-López, J.; Mira, A.; Castilla, D.; Casteleyn, S. Smartphone apps for the treatment of mental disorders: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e14897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; He, X.; Shen, Y.; Yu, H.; Pan, J.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, J.; Bao, Y. Effectiveness of smartphone app–based interactive management on glycemic control in Chinese patients with poorly controlled diabetes: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e15401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luna, I.R.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Mobile payment is not all the same: The adoption of mobile payment systems depending on the technology applied. Technol. Forecast Soc. Change 2019, 146, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivari, N.; Sharma, S.; Ventä-Olkkonen, L. Digital transformation of everyday life–How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, J.A.; Sandra, D.A.; Colucci, É.S.; Al Bikaii, A.; Chmoulevitch, D.; Nahas, J.; Raz, A.; Veissière, S.P. Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.Q.; Cheng, J.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Yang, X.Q.; Zheng, J.W.; Chang, X.W.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; et al. Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 92, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, H.; Al Fayez, R.Q.; Al Refaei, A.; Shewaikani, N.; Khawaldah, H.; Abu-Shanab, S.; Al-Hussaini, M. Smartphone use among university students during COVID-19 quarantine: An ethical trigger. Public Health Front. 2021, 9, 600134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, W.S.W.; Sim, S.T.; Tan, K.A.; Bahar, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Mahadevan, R.; Jaafar, N.R.N.; Baharudin, A.; Abdul Aziz, M. The relations of internet and smartphone addictions to depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidality among public university students in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Jang, H.M.; Lee, Y.; Lee, D.; Kim, D.J. Effects of internet and smartphone addictions on depression and anxiety based on propensity score matching analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.S. Examination of smartphone dependence: Functionally and existentially dependent behavior on the smartphone. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.S.; Seo, B.K. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: Prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol. Open 2018, 5, 2055102918755046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafaoglu, R.; Yasaci, Z.; Zirek, E.; Griffiths, M.D.; Ozdincler, A.R. The relationship between smartphone addiction and musculoskeletal pain prevalence among the young population: A cross-sectional study. Korean J. Pain 2021, 34, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowsi, K.; Subramanian, K. Smartphone addiction and physical activity—Time to strike the balance. EC Psychol. Psychiatr. 2019, 8, 1046–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I.; Kocadag Unver, T. Moderating role of gender in the relationship between big five personality traits and smartphone addiction. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, H.J.; Achab, S.; Billieux, J.; Bowden-Jones, H.; Carragher, N.; Demetrovics, Z.; Higuchi, S.; King, D.L.; Mann, K.; Potenza, M.; et al. Including gaming disorder in the ICD-11: The need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective: Commentary on: A weak scientific basis for gaming disorder: Let us err on the side of caution (van Rooij et al., 2018). J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, S.; Gül, H.; Sertçelik, M.; Gül, A.; Gürel, Y.; Kılıç, B.G. The relationship between problematic smartphone use and psychiatric symptoms among adolescents who applied to psychiatry clinics. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haripriya, S.; Samuel, S.E.; Megha, M. Correlation between smartphone addiction, sleep quality and physical activity among young adults. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Su, A. Intervention of smartphone addiction. In Multifaceted Approach to Digital Addiction and Its Treatment; Bozoglan, B., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ahn, H.; Choi, S.; Choi, W. The SAMS: Smartphone addiction management system and verification. J. Med. Syst. 2014, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Chun, M.Y.; Lee, I.; Yoo, Y.G.; Kim, M.J. The effect of mind subtraction meditation intervention on smartphone addiction and psychological wellbeing among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, J. Conceptualizing effective interventions for smartphone addiction among Korean female adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 84, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lin, A.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y.; Hong, S. Global research trends of geographical information system from 1961 to 2010: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Muñoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M.J. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Bellamy, M.A.; Basole, R.C. Visual analytics for supply network management: System design and evaluation. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 91, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceneda, D.; Gschwandtner, T.; Miksch, S. A review of guidance approaches in visual data analysis: A multifocal perspective. Comput. Graph. Forum 2019, 38, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewska, M.; Kostrzewski, M. Sustainable business models: A bibliometric performance analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ebrahim, N.A. A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1305.0377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.K.; Song, M.; Ding, Y. Content-based author co-citation analysis. J. Infometr. 2014, 8, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, R.; Afzal, M.T. Sections-based bibliographic coupling for research paper recommendation. Scientometrics 2019, 119, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasseh, A.A.; Soheili, F.; Moghaddam, H.S.; Chelak, A.M. Intellectual structure of knowledge in iMetrics: A co-word analysis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2017, 53, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelodar, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: Models, applications, a survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 15169–15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Ponraj, M. Performance evaluation of Latent Dirichlet Allocation in text mining. In Proceedings of the 2011 Eighth International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Grimson, E. Spatial Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2007, 20. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2007/hash/ec8956637a99787bd197eacd77acce5e-Abstract.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, U.; Shah, A. Topic modeling using latent Dirichlet allocation: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponweiser, M. Latent Dirichlet Allocation in R. 2012. Available online: https://research.wu.ac.at/en/publications/latent-dirichlet-allocation-in-r-3 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Blei, D.; Ng, A.; Jordan, M. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2001, 14. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2001/hash/296472c9542ad4d4788d543508116cbc-Abstract.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Anandkumar, A.; Foster, D.P.; Hsu, D.J.; Kakade, S.M.; Liu, Y.K. A Spectral Algorithm for Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2012/hash/15d4e891d784977cacbfcbb00c48f133-Abstract.html (accessed on 30 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Petterson, J.; Buntine, W.; Narayanamurthy, S.; Caetano, T.; Smola, A. Word Features for Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2010, 23. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2010/hash/db85e2590b6109813dafa101ceb2faeb-Abstract.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Canini, K.; Shi, L.; Griffiths, T. Online inference of topics with latent Dirichlet allocation. In Proceedings of the Twelth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 15 April 2009; Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v5/canini09a (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Tateno, M.; Kim, D.J.; Teo, A.R.; Skokauskas, N.; Guerrero, A.P.; Kato, T.A. Smartphone addiction in Japanese college students: Usefulness of the Japanese version of the smartphone addiction scale as a screening tool for a new form of internet addiction. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Huang, S.; Nie, C.; Yan, J.J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. Trajectory of problematic smartphone use among adolescents aged 10–18 years: The roles of childhood family environment and concurrent parent–child relationships. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.Y.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, T.J.; Huang, D.H. The relationship among the social norms of college students, and their interpersonal relationships, smartphone use, and smartphone addiction. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Jeong, Y.; Suh, B.; Gweon, G. Is smartphone addiction different from Internet addiction? Comparison of addiction-risk factors among adolescents. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ahn, J.S.; Min, S.; Kim, M.H. Psychological characteristics and addiction propensity according to content type of smartphone use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.I. The relationship between life stress and smartphone addiction on Taiwanese university student: A mediation model of learning self-efficacy and social self-efficacy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, M.A.; Zhao, P.; Custer, B.E. Short-term longitudinal relationships between smartphone use/dependency and psychological well-being among late adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, P.; Torres, A.; Herrero, J.; Urueña, A. Smartphone addiction and social support: A three-year longitudinal study. Interv. Psicosoc. Psychosoc. Interv. 2019, 28, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Long, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, T.Q.; Billieux, J. Factor structure and measurement invariance of the problematic mobile phone use questionnaire-short version across gender in Chinese adolescents and young adults. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saggaf, Y.; O’Donnell, S.B. Phubbing: Perceptions, reasons behind, predictors, and impacts. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 1, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Nandavar, S.; Newton, J.D.A.; Demant, D.; Phillips, J.G. Problematic use of mobile phones in Australia… is it getting worse? Front. Psychiatry 2019, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, S.H.; Kim, D.J. Smart healthcare systems and precision medicine. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 1192, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili Rad, M.; Ahmadi, F. A new method to measure and decrease the online social networking addiction. Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2018, 10, e12330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Gao, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, T.; Chen, Q. Parent–child relationships and mobile phone addiction tendency among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction and the moderating role of peer relationships. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Wu, A.M. Effects of smartphone addiction on sleep quality among Chinese university students: The mediating role of self-regulation and bedtime procrastination. Addict. Behav. 2020, 111, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.W.; Ho, R.C. Tapping onto the potential of smartphone applications for psycho-education and early intervention in addictions. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throuvala, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Rennoldson, M.; Kuss, D.J. Psychosocial skills as a protective factor and other teacher recommendations for online harms prevention in schools: A qualitative analysis. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 648512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, S.; Castro, R.P.; Wenger, A.; Schaub, M.P. Efficacy of a smartphone-based coaching program for addiction prevention among apprentices: Study protocol of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zou, L.; Becker, B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Yu, Q.; Chen, S.T.; Demetrovics, Z.; Jiao, C.; Chi, X.; Chen, A.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of mind–body exercise versus cognitive behavioral therapy for college students with problematic smartphone use: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Ment. Health Promo. 2020, 22, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidmar, A.P.; Pretlow, R.; Borzutzky, C.; Wee, C.P.; Fox, D.S.; Fink, C.; Mittelman, S.D. An addiction model-based mobile health weight loss intervention in adolescents with obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Mindfulness and cell phone dependence: The mediating role of social adaptation. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2021, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.C.Y.; Lee, R.L.T. Effects of a group mindfulness-based cognitive programme on smartphone addictive symptoms and resilience among adolescents: Study protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretlow, R.A.; Stock, C.M.; Allison, S.; Roeger, L. Treatment of child/adolescent obesity using the addiction model: A smartphone app pilot study. Child Obes. 2015, 11, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.K.; Choi, J. Predictors of sleep quality among young adults in Korea: Gender differences. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Jeong, K.H.; Cho, H.J. The effects of children’s smartphone addiction on sleep duration: The moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buctot, D.B.; Kim, N.; Kim, J.J. Factors associated with smartphone addiction prevalence and its predictive capacity for health-related quality of life among Filipino adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Ding, J.E.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Fu, H. A pilot study of a group mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for smartphone addiction among university students. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, I.; Al Mamun, F.; Sikder, M.T.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Zou, L.; Guo, T.; Mamun, M.A. Prevalence and associated factors of problematic smartphone use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Bangladeshi study. Risk Manag. Healthc Policy 2021, 14, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Hwang, S.S.H.; Lee, M.S.; Bhang, S.Y. Food addiction and emotional eating behaviors co-occurring with problematic smartphone use in adolescents? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 3 | 2.9% |

| 2015 | 2 | 1.9% |

| 2016 | 4 | 3.8% |

| 2017 | 6 | 5.8% |

| 2018 | 13 | 12.5% |

| 2019 | 11 | 10.6% |

| 2020 | 27 | 26% |

| 2021 | 38 | 36.5% |

| Total | 104 | 100% |

| Research Topics | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age group (children, adolescents, college students, adults) | 90 | 30.61% |

| 2 | Mental state (well-being, boredom, loneliness, fear of missing out, mental disorders, inattention) | 58 | 19.73% |

| 3 | Usage behavior problems (dependence, attachment, gaming, social media) | 51 | 17.35% |

| 4 | Living conditions (stress, learning, society, sleep, family, bullying) | 45 | 15.31% |

| 5 | Physical problems (obesity, bone problems, posture) | 11 | 3.74% |

| 6 | Supervision and management system | 11 | 3.74% |

| 7 | Personality factors (emotional imbalance) | 11 | 3.74% |

| 8 | Gender | 8 | 2.72% |

| 9 | Work | 5 | 1.70% |

| 10 | COVID-19 | 4 | 1.36% |

| Subject | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Students (children, adolescents, college students) | 59 | 56.7% |

| General public | 34 | 32.7% |

| Parents | 6 | 5.77% |

| General workers (scholars, farmers, craftsmen, merchants) | 4 | 3.85% |

| Patients with mental disorders | 1 | 0.96% |

| Intervention | Definition | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological intervention | Smartphone addiction is related to depression and suicidality and addicts desire a sense of security by using their smartphones | 48 | 26.97% |

| Social support | Smartphone addicts require support from peers or the surrounding environment | 27 | 15.17% |

| Lifestyle intervention | Restrictions on smartphone usage in daily life | 25 | 14.04% |

| Technological intervention | The usage of mobile phones is related to the development of apps | 19 | 10.67% |

| Family intervention | Smartphone addicts increase family interactions through restrictions and influence placed upon by family members | 18 | 10.11% |

| Medical intervention | Treatment associating smartphone addiction with psychological and physical problems | 14 | 7.87% |

| Educational intervention | Smartphone addiction and psychosocial education courses | 12 | 6.74% |

| Exercise intervention | Focus on exercise and reduce the temptation to use phones | 8 | 4.49% |

| Mindfulness intervention | Enhancing self-belief and facilitating social adjustment | 5 | 2.8% |

| Meditation intervention | Smartphone addiction and intervention through meditation | 2 | 1.12% |

| Ranking | Author | Total Citations | Ranking | Author | Total Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | J. D. Elhai | 80 | 6 | K. Demirci | 34 |

| 2 | J. Billieux | 62 | 7 | O. Lopez-Fernandez | 28 |

| 3 | M. Kwon | 40 | 7 | D. Kardefelt-Winther | 28 |

| 4 | K. S. Young | 36 | 9 | A. J. A. M. van Deursen | 27 |

| 5 | D. J. Kuss | 35 | 10 | I. Leung | 26 |

| Ranking | Country | Total Citations | Ranking | Country | Total Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 645 | 6 | Israel | 77 |

| 2 | South Korea | 304 | 7 | Australia | 71 |

| 3 | Taiwan | 193 | 8 | Singapore | 54 |

| 4 | USA | 105 | 9 | Spain | 42 |

| 5 | UK | 80 | 9 | Austria | 42 |

| Ranking | Keyword | Occurrence | Ranking | Keyword | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smartphone addiction | 39 | 7 | Depression | 8 |

| 2 | Problematic smartphone use | 23 | 8 | Anxiety | 8 |

| 3 | Smartphone | 17 | 8 | Mental health | 8 |

| 4 | Adolescents | 16 | 8 | Intervention | 8 |

| 5 | Social media | 9 | 9 | College students | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.-Y.; Chou, W.-H. A Bibliometric Analysis to Identify Research Trends in Intervention Programs for Smartphone Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053840

Wu Y-Y, Chou W-H. A Bibliometric Analysis to Identify Research Trends in Intervention Programs for Smartphone Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053840

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yi-Ying, and Wen-Huei Chou. 2023. "A Bibliometric Analysis to Identify Research Trends in Intervention Programs for Smartphone Addiction" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053840

APA StyleWu, Y.-Y., & Chou, W.-H. (2023). A Bibliometric Analysis to Identify Research Trends in Intervention Programs for Smartphone Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053840