Environmental Health Knowledge Does Not Necessarily Translate to Action in Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Surveys

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

3.2. Environmental Health and Health Knowledge

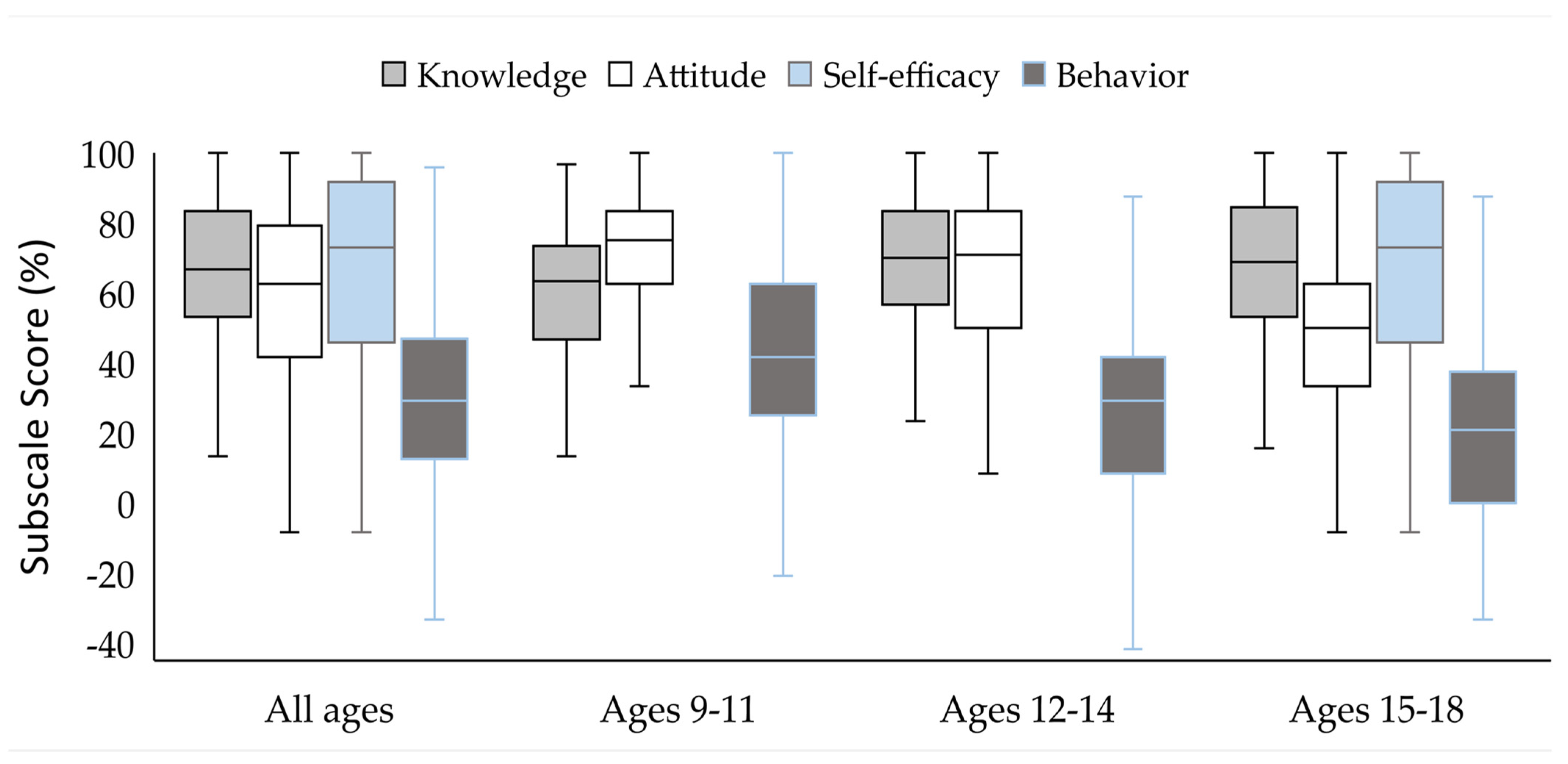

3.3. Behavior Is Weakly Associated with Environmental Health Knowledge

3.4. Factors Associated with Behavior Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy, J.A. Environmental Exposures and Child Health: What we Might Learn in the 21st Century from the National Children’s Study? Environ. Health Insights 2008, 2, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiarasan, S.; Hüls, A. Impact of Environmental Injustice on Children’s Health-Interaction between Air Pollution and Socioeconomic Status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyatt, R.M.; Perzanowski, M.S.; Just, A.C.; Rundle, A.G.; Donohue, K.M.; Calafat, A.M.; Hoepner, L.A.; Perera, F.P.; Miller, R.L. Asthma in Inner-City Children at 5–11 Years of Age and Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates: The Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiotiu, A.I.; Novakova, P.; Nedeva, D.; Chong-Neto, H.J.; Novakova, S.; Steiropoulos, P.; Kowal, K. Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.M.; Kahn, R.S.; Froehlich, T.; Auinger, P.; Lanphear, B.P. Exposures to Environmental Toxicants and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in U.S. Children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1904–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, L.; Julvez, J.; López-Vicente, M.; Warembourg, C.; Tamayo-Uria, I.; Philippat, C.; Gützkow, K.B.; Guxens, M.; Andrusaityte, S.; Basagaña, X.; et al. Early-life environmental exposure determinants of child behavior in Europe: A longitudinal, population-based study. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lewis, G. Environmental toxicity and poor cognitive outcomes in children and adults. J. Environ. Health 2014, 76, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yolton, K.; Dietrich, K.; Auinger, P.; Lanphear, B.P.; Hornung, R. Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Cognitive Abilities among U.S. Children and Adolescents. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Schechter, C.B.; Lipton, J.M.; Fahs, M.C.; Schwartz, J. Environmental pollutants and disease in American children: Estimates of morbidity, mortality, and costs for lead poisoning, asthma, cancer, and developmental disabilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharf Higgins, J.; Begoray, D.; MacDonald, M. A social ecological conceptual framework for understanding adolescent health literacy in the health education classroom. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 44, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, F.; Righi, V.; Toran, R.; Errandonea, L.P.; Ortiz, R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Creus, J.; Basagaña, X.; Balestrini, M. Co-creating a local environmental epidemiology study: The case of citizen science for investigating air pollution and related health risks in Barcelona, Spain. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebow-Skelley, E.; Fremion, B.B.; Quinn, M.; Makled, M.; Keon, N.B.; Jelenek, J.; Crowley, J.A.; Pearson, M.A.; Schulz, A.J. “They Kept Going for Answers”: Knowledge, Capacity, and Environmental Health Literacy in Michigan’s PBB Contamination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. Developing Health Literacy Skills in Children and Youth: Proceedings of a Workshop; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Keselman, A.; Levin, D.M.; Kramer, J.F.; Matzkin, K.; Dutcher, G. Educating Young People about Environmental Health for Informed Social Action. Umw. Gesundh. Online 2011, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mifsud, M.C. A Meta-Analysis of Global Youth Environmental Knowledge, Attitude and Behavior Studies. US-China Educ. Rev. B 2012, 2, 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Gambro, J.S.; Switzky, H.N. A National Survey of Environmental Knowledge in High School Students: Levels of Knowledge and Related Variables; ERIC Clearinghouse: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1994.

- Barrett, E.S.; Sathyanarayana, S.; Janssen, S.; Redmon, J.B.; Nguyen, R.H.N.; Kobrosly, R.; Swan, S.H.; Team, T.S. Environmental health attitudes and behaviors: Findings from a large pregnancy cohort study. Eur. J. Obs. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 176, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibberd, M.; Nguyen, A. Climate change communications & young people in the Kingdom: A reception study. Int. J. Media Cult. Politics 2013, 9, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutaleva, A.; Martyushev, N.; Nikonova, Z.; Savchenko, I.; Abramova, S.; Lubimova, V.; Novgorodtseva, A. Environmental Behavior of Youth and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palupi, T.; Sawitri, D.R. The Importance of Pro-Environmental Behavior in Adolescent. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 31, 09031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I. Sustainability in Youth: Environmental Considerations in Adolescence and Their Relationship to Pro-environmental Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstadt, M.S. Alcohol and drug education: Models and outcomes. Health Educ. Monogr. 1978, 6, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, E.N.; David, H.; Chinwe, N.C.; Ndubuisi, O.E. Knowledge of Environmental Sanitation among Secondary School Students in Etche, Rivers State. Age 2020, 10, 310. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, A.R.; May, K.; Murphy, J.; Gross, A.; Carlsten, E. Environmental Health Literacy as Knowing, Feeling, and Believing: Analyzing Linkages between Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status and Willingness to Engage in Protective Behaviors against Health Threats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, J.L.; Malkus, A.J. Adolescent Environmental Behaviors: Can Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Efficacy Make a Difference? Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naquin, M.; Cole, D.; Bowers, A.; Walkwitz, E. Environmental Health Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Students in Grades Four through Eight. Environ. Health 2011, 6, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Strecher, V.J.; DeVellis, B.M.; Becker, M.H.; Rosenstock, I.M. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ. Q. 1986, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawitri, D.R.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hadi, S.P. Pro-environmental Behavior from a SocialCognitive Theory Perspective. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, N.L.; Wellman, N.S.; Amundson, D.R. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in Content Analysis: Some Common Misconceptions and Recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2006, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heallth Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Bickenbach, J. WHO’s Definition of Health: Philosophical Analysis. In Handbook of the Philosophy of Medicine; Schramme, T., Edwards, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K.M.; Mirabelli, M.C. Outdoor Air Quality Awareness, Perceptions, and Behaviors Among U.S. Children Aged 12-17 Years, 2015-2018. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2021, 68, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, C.; Anderson, A. Increasing Local Salience of Climate Change: The Un-tapped Impact of the Media-science Interface. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Lung Association. State of the Air 2016; American Lung Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Logue, J.M.; Price, P.N.; Sherman, M.H.; Singer, B.C. A Method to Estimate the Chronic Health Impact of Air Pollutants in U.S. Residences. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1995. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/121457 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Gray, K.M. From Content Knowledge to Community Change: A Review of Representations of Environmental Health Literacy. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, S.; O’Fallon, L. The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy-From Its Roots to Its Future Potential. Environ. Health Perspect 2017, 125, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Ecological behavior’s dependency on different forms ofknowledge. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 52, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnim Wiek, L.W.; Charles, L. Redman. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Otto, S.; Diaz-Marin, J.S. A diagnostic environmental knowledge scale for Latin America. Psyecology Rev. Bilingüe Psicol. Ambient. 2014, 5, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Maki, A.; Montanaro, E.; Avishai-Yitshak, A.; Bryan, A.; Klein, W.M.; Miles, E.; Rothman, A.J. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2016, 35, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, A.; Fassler, J.; Fox, K.R.; Schleider, J.L. The impact of COVID-19 on U.S. adolescents: Loss of basic needs and engagement in health risk behaviors. Curr. Psychol. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Aunan, K.; Chowdhury, S.; Lelieveld, J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 18984–18990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, E.M.; Szefler, S. Ongoing asthma management in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: To step down or not to step down? Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, E.M.; Choi, Y.; Ha, E. Impact of an Educational Program on Behavioral Changes toward Environmental Health among Laotian Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, N.L.; Okere, U.C.; Kaufman, Z.B.; Ekenga, C.C. Enhancing Educational and Environmental Awareness Outcomes Through Photovoice. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 16094069211016719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerden, M.D.; Witt, P.A. The impact of direct and indirect experiences on the development of environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Environmental Health Science. Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/translational/peph/webinars/health_literacy/index.cfm (accessed on 23 November 2019).

- Goldman, D.; Assaraf, O.B.Z.; Shaharabani, D. Influence of a Non-formal Environmental Education Programme on Junior High-School Students’ Environmental Literacy. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 515–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyes, E.; Stanisstreet, M. Environmental Education for Behaviour Change: Which actions should be targeted? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 1591–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.M.; Triana, V.; Lindsey, M.; Richmond, B.; Hoover, A.G.; Wiesen, C. Knowledge and Beliefs Associated with Environmental Health Literacy: A Case Study Focused on Toxic Metals Contamination of Well Water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, M.; Chen, S.R.; Ben, R.; Manoogian, M.; Spradlin, J. Defining Environmental Health Literacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J.; Powell, R.B.; Frensley, B.T. Environmental education, age, race, and socioeconomic class: An exploration of differential impacts of field trips on adolescent youth in the United States. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, D.; Claustro, M.; Wong, M.; Bejarano, E.; Olmedo, L.; English, P. Developing Youth Environmental Health Literacy and Civic Leadership through Community Air Monitoring in Imperial County, California. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, D.S.; Minkler, M.; Parra, K.L.; Mundo, C.; Gonzalez, J.E.C.; Jimenez, R.; Vera, C.; Harley, K.G. Improving Latino Youths’ Environmental Health Literacy and Leadership Skills Through Participatory Research on Chemical Exposures in Cosmetics: The HERMOSA Study. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2016, 36, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagisetty, R.M.; Autenrieth, D.A.; Storey, S.R.; Macgregor, W.B.; Brooks, L.C. Environmental health perceptions in a superfund community. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, S.C.; Hood, D.B.; Zokovitch, J.; Close, F.T. Blueprint for communicating risk and preventing environmental injustice. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2010, 21, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgren, S.D.; Boyles, R.R.; Cronk, R.D.; Duncan, C.G.; Kwok, R.K.; Lunn, R.M.; Osborn, K.C.; Thessen, A.E.; Schmitt, C.P. Catalyzing Knowledge-Driven Discovery in Environmental Health Sciences through a Community-Driven Harmonized Language. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, J.K.; Zimmerman, K.; Erbstein, N. Youth-Led Research and Evaluation: Tools for Youth, Organizational, and Community Development. New Dir. Eval. 2003, 2003, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague Martinez, L.S.; Reich, A.J.; Flores, C.A.; Ndulue, U.J.; Brugge, D.; Gute, D.M.; Perea, F.C. Critical Discourse, Applied Inquiry and Public Health Action with Urban Middle School Students: Lessons Learned Engaging Youth in Critical Service-Learning. J. Community Pract. 2017, 25, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague Martinez, L.S.; Gute, D.M.; Ndulue, U.J.; Seller, S.L.; Brugge, D.; Peréa, F.C. All public health is local. Revisiting the importance of local sanitation through the eyes of youth. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1058–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Age Groups (Years), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 452) | 9–11 (n = 127) | 12–14 (n = 135) | 15–18 (n = 190) | |

| Age, years (years) | 13.6 ± 2.6 | 10.1 ± 0.8 | 13.3 ± 0.6 | 16.2 ± 0.9 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 268 (59.3) | 65 (51.2) | 74 (54.8) | 129 (67.9) |

| Male | 181 (40.1) | 60 (47.2) | 60 (44.4) | 61 (32.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | ||||

| Yes | 22 (4.9) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (3.7) | 9 (4.7) |

| No | 424 (93.8) | 118 (92.9) | 128 (94.8) | 178 (93.7) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 411 (90.9) | 119 (93.7) | 123 (91.1) | 169 (88.9) |

| Black/African American | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (1.6) |

| Native American | 5 (1.1) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 24 (5.3) | 4 (3.2) | 7 (5.2) | 13 (6.8) |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 28 (6.2) | 5 (3.9) | 5 (3.7) | 18 (9.5) |

| Suburban | 395 (87.4) | 114 (89.8) | 124 (91.9) | 157 (82.6) |

| Urban | 26 (5.8) | 7 (5.5) | 4 (2.9) | 15 (7.9) |

| Parents’ employment status | ||||

| Both parents unemployed | 11 (2.4) | 3 (2.4) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (3.2) |

| Both parents employed | 297 (65.7) | 73 (57.5) | 94 (69.6) | 130 (68.4) |

| One parent employed | 111 (24.6) | 25 (19.7) | 35 (25.9) | 51 (26.8) |

| Do not know | 32 (7.1) | 26 (20.5) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (1.6) |

| Asthma history | ||||

| Yes | 62 (13.7) | 14 (11.1) | 19 (14.1) | 29 (15.3) |

| No | 386 (85.4) | 112 (88.2) | 114 (84.4) | 160 (84.2) |

| Questions | Themes | Subthemes and Youth Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| What worries you about the environment? | Air pollution | Smoking: Something that worries me about the environment is when people like smokers start polluting the air. Also, some trains pollute the air when they go down the train tracks (10- year old female). |

| Environmental smoke: Air pollution worries me about the environment because there will be too much smoke in the earth (9-year old male). | ||

| Global warming: I hear about global warming often, and it scares me that so many people don’t take care of the environment (16-year old female). | ||

| Waste | Littering: When people litter in parks or even just on the street (9-year old female) | |

| Overfull landfills: I worry about global warming and things that sit in the landfill forever when they could be biodegradable somewhere else, e.g., compost pile, back yard (12-year old female). | ||

| Wild and human life | Health impact: That people will get sick, and more animals will die because of pollution (13-year old male). | |

| Plant and animal loss: All the polluted air and oil in the water that are harming animals and plants (18-year old female). | ||

| How or in what ways does the environment affect health? | Air pollution | Smoking: If someone around you is smoking and you breathe in that air a lot, you could get sick (9-year old female). |

| Environmental smoke: Pollution, such as smoke, makes it difficult to breathe (15-year old female). | ||

| Health and illness state | Human needs from the environment: The environment keeps me healthy and strong; If there aren’t many trees, we wouldn’t have oxygen. The environment affects my health by giving me air, water, and food; I have allergies to some of the plants and things. It gives me allergies, colds, and sometimes fevers (9-year old female). | |

| What can you do to help (or protect) the environment? | Do not pollute | Clean up/not littering I can pick up litter and help others become more aware of the environment (13-year old male). |

| Pro-environmental behaviors: I can pick up litter and help others become more aware of the environment (13-year old male). | ||

| Save resources | Save wildlife: I can recycle, try not to waste electricity, and try not to waste water, plant trees or other plants, and many other things (14-year old male). | |

| Save energy/not waste: I can use less water and just basically reduce my carbon footprint by recycling and using clean fuel systems like wind power or hydroelectricity (18-year old female). |

| Age Group (Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating (n (%) within Age Group) | All (n = 448) | 9–11 (n = 125) | 12–14 (n = 134) | 15–18 (n = 189) |

| Don’t Know | 13 (2.9) | 10 (8.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) |

| Poor | 103 (23.0) | 54 (43.2) | 26 (19.4) | 23 (12.2) |

| Fair | 264 (58.9) | 56 (44.8) | 93 (69.4) | 115 (60.8) |

| Good | 38 (8.5) | 5 (4.0) | 13 (9.7) | 20 (10.6) |

| Very Good | 30 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 29 (15.3) |

| Age Groups (y) | Behavior & Knowledge | Behavior & Attitude | Behavior & Self-efficacy | Knowledge & Attitude | Knowledge & Self-Efficacy | Self-Efficacy & Attitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 442) | r = 0.22 ** | r = 0.54 | r = 0.51 ** | r = 0.38 ** | r = 0.47 ** | r = 0.50 ** |

| 9–11 (n = 127) 12–14 (n = 123) | r = 0.39 ** r = 0.29 ** | r = 0.59 ** r = 0.41 ** | ------ ------ | r = 0.51 ** r = 0.55 ** | ------ ------ | ------ ------ |

| 15–18 (n = 188) | r = 0.21 ** | r = 0.49 ** | r = 0.51 ** | r = 0.45 ** | r = 0.47 ** | r = 0.50 ** |

| Behaviors | Knowledge | Attitudes | Self-Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation in environment-related classes, activities, and/or clubs | ||||

| Yes (n = 86) | 26.2 ± 25.3 | 73.9 ± 20.9 | 54.5 ± 20.8 | 75.0 (35.4) |

| No (n = 102) | 16.3 ± 23.4 | 65.1 ± 19.1 | 44.6 ± 23.3 | 66.6 (45.8) |

| t = 2.8, p = 0.006 | t = 3.03, p = 0.003 | t = 3.03, p = 0.003 | Z = 2.3, p = 0.02 | |

| School Type * | ||||

| Private (n = 56) | 24.8 ± 25.4 | 73.4 ± 17.5 | 56.8 ± 18.8 | 80.5 (41.7) |

| Public (n = 73) | 19.0 ± 23.1 | 67.2 ± 21.2 | 46.4 ± 20.7 | 70.8 (43.8) |

| t = 1.3, p = 0.2 | t = 1.7, p = 0.08 | t = 2.9, p = 0.004 | Z = 1.4, p = 0.2 | |

| Parent employment | ||||

| 2 parents working (n = 129) | 20.8 (37.5) | 71.3 ±19.4 | 48.8 ± 22.2 | 75.0 (41.7) |

| One parent working (n = 50) | 16.7 (34.4) | 65.2 ± 21.6 | 51.9 ± 23.2 | 56.3 (51.0) |

| Z = 2.2, p = 0.03 | t = 1.8, p = 0.07 | t = 0.8, p = 0.4 | Z = 2, p = 0.045 | |

| Asthma status | ||||

| Asthmatic (n = 29) | 25% ± 25.9 | 72.3% ± 20.2 | 49.2% ± 24.3 | 91.7 (35.4) |

| No asthma (n = 157) | 19.8% ± 24.1 | 68.7% ± 20.5 | 49.1% ± 22.5 | 66.6 (41.7) |

| t = 1.1, p = 0.3 | t = 0.9, p = 0.4 | t = 0.007, p = 0.9 | Z = 2.7, p = 0.007 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, S.; Martin, L.J.; Baker, T.A.; Roberts, E.; Rios-Santiago, P.; Kaufhold, R.; Butsch Kovacic, M. Environmental Health Knowledge Does Not Necessarily Translate to Action in Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053971

Elshaer S, Martin LJ, Baker TA, Roberts E, Rios-Santiago P, Kaufhold R, Butsch Kovacic M. Environmental Health Knowledge Does Not Necessarily Translate to Action in Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053971

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Shereen, Lisa J. Martin, Theresa A. Baker, Erin Roberts, Paola Rios-Santiago, Ross Kaufhold, and Melinda Butsch Kovacic. 2023. "Environmental Health Knowledge Does Not Necessarily Translate to Action in Youth" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053971

APA StyleElshaer, S., Martin, L. J., Baker, T. A., Roberts, E., Rios-Santiago, P., Kaufhold, R., & Butsch Kovacic, M. (2023). Environmental Health Knowledge Does Not Necessarily Translate to Action in Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053971