Exploring Transfer Potentials of the IMPROVEjob Intervention for Strengthening Workplace Health Management in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Germany: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

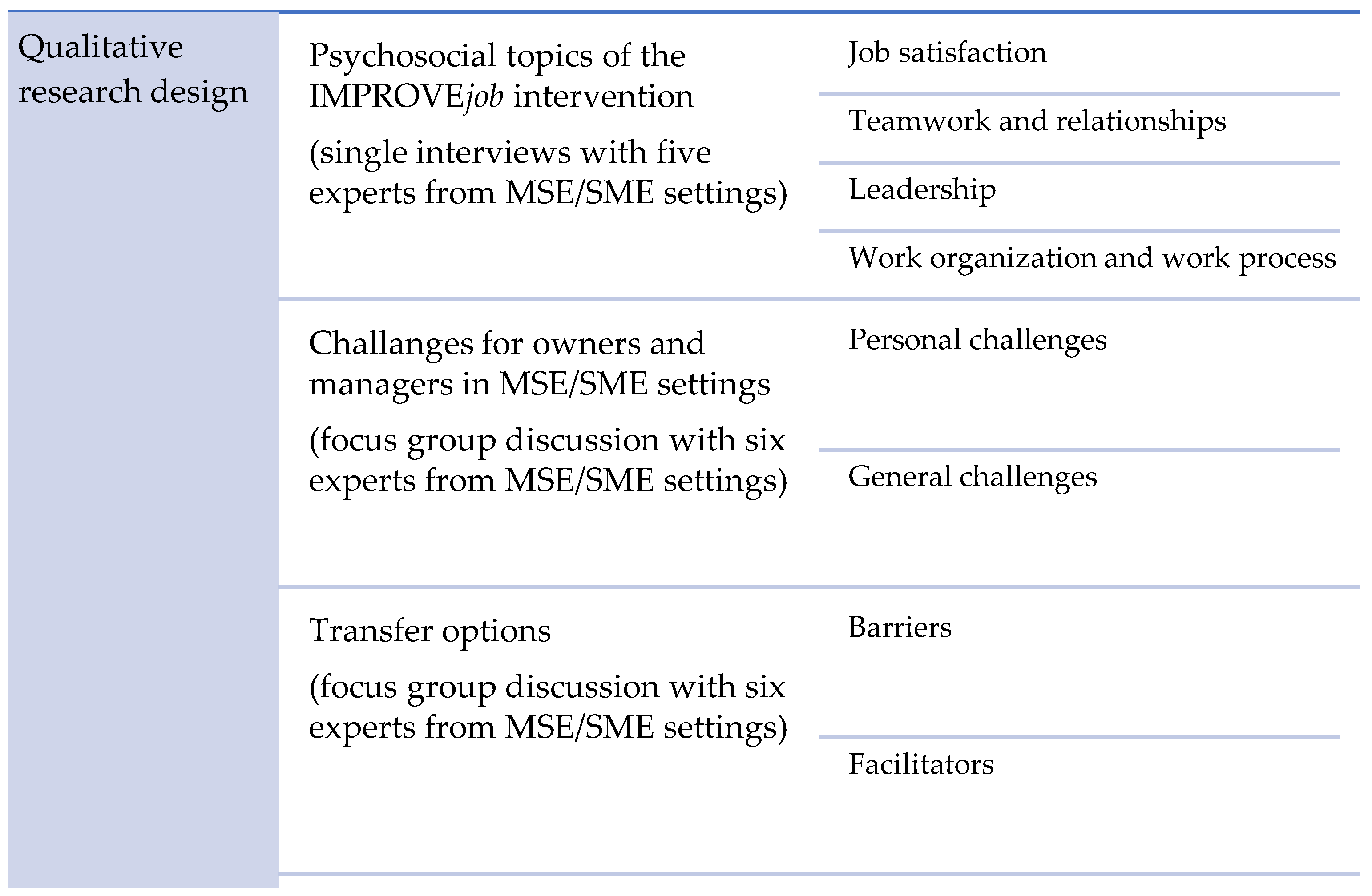

- (1)

- the relevance of psychosocial topics of the original IMPROVEjob intervention in different MSE/SME settings;

- (2)

- the main challenges faced by owners and managers in different MSE/SME settings;

- (3)

- as well as, possible transfer options (barriers and facilitators) regarding the implementation of the IMPROVEjob intervention into other MSE/SME settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Preparation of the Field Work

2.2. Recruitment and Qualitative Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Psychosocial Topics of the IMPROVEjob Intervention

3.2. Challenges for Owners and Managers in MSE/SME Settings in Germany

- Personal challenges comprise leadership issues (e.g., lack of leadership role understanding; little/hardly any time for leadership issues; leadership not seen as a responsibility; leadership tasks as a cost factor (no sales)/low priority; leadership of larger groups), work overload (e.g., multiple roles at the same time; supervision of many employees; and few resources), and possible knowledge gaps of managers and owners (e.g., little knowledge about mental stress and strain factors; attitude: “everyone is responsible for themselves”).

- General challenges include more emerging topics (e.g., demographic change and age-appropriate working design, dealing with diversity, and lifelong learning), organizational issues (e.g., vacation planning and sick leave; employee meetings; communication with customers; handling time management; cross-industry competition for skilled workers), team care and staff management (e.g., handling small teams; finding and retaining staff; handling low commitment to the company; different working attitude of the present generation; staff shortage; handling high stress and group dynamics; reaching all employees; equal treatment/fairness; communication under stress), and challenges regarding the implementation of changes (e.g., no facilities; no internal support; information overload; only general support; dealing with works council and management; no networking; no organizational structures in the company).

3.3. Transfer Options Barriers and Facilitators for MSE/SME Settings in Germany

3.4. Evaluation of the Conducted Focus Group Discussion

4. Discussion

- The separation into two workshops (leaders and leaders with teams) seems appropriate also for other MSE/SME settings. Participation in workshops should be made as easy as possible for the participants (e.g., regarding access, duration). The specific objectives and implementation of the two workshops should be determined in advance with owners and managers of the MSE/SME settings.

- The topics of the IMPROVEjob intervention [30,33] seemed to be appropriate for other MSE/SME settings; however, they should be linked to topics that are currently relevant, such as a shortage of skilled workers. In general, it seems to be beneficial if the participants (owners/managers and their teams) themselves determine in advance which topics they would like to focus on during the workshops.

- The didactic parts of the IMPROVEjob intervention could be expanded, with more involvement of skills labs, interdisciplinary exchanges, peer learning, and networking opportunities.

- The IMPROVEjob facilitators should be available during the implementation period for further questions and problems, so that the IMPROVEjob intervention can be carried out as planned. MSE/SME settings should be provided with special support during the implementation process.

- The implementation of psychosocial topics such as job satisfaction, leadership, teamwork, and social relationships, as well as work organization and work process should be further promoted in MSE/SME settings. Therefore, specific campaigns are useful to inform and raise awareness on these topics in MSE/SME settings.

- Due to limited personnel and time resources in MSE/SME settings, offers and campaigns with easy access are to be preferred. The Cardiff Memorandum on Workplace Health Promotion in SME settings, for example, identified limited resources as the main barrier for the implementation of workplace health promotion activities [34]. Another study also identified workload as the main barrier for participation in workplace health promotion offers [35]. Frequently, smaller companies have limited time and resources for promoting the well-being and health of employees; therefore, knowledge on workplace health promotion should be adapted to the needs of smaller companies [34].

- Smaller businesses differ from larger companies not only in their number of employees, structural organization, and financial resources, but also in terms of psychosocial experiences and the central impact of owners and managers [14]. Owners and managers in MSE/SME settings should therefore be supported and accompanied with regards to addressing psychosocial demands in their companies. External support could also be helpful, and should be available as a contact person for a longer period of time. In this context, the question should be discussed which persons, even outside of a study context, are available, and could provide support and raise awareness for WHM in MSE/SME settings. In our view, people with a professional background in occupational medicine would be particularly helpful here.

- Besides personal challenges for managers, general challenges like emerging topics, organizational issues, and challenges regarding team care and staff management should also be considered and addressed.

- It is important to provide an environment and a participative process where company owners, managers, and employees discuss the implementation of measures for the promotion and implementation of WHM on a long-term basis.

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothe, I.; Adolph, L.; Beermann, B.; Schütte, M.; Windel, A.; Grewer, A.; Lenhardt, U.; Michel, J.; Thomson, B.; Formazin, M. Psychische Gesundheit in der Arbeitswelt—Wissenschaftliche Standort Bestimmung [Mental Health in the Working World—Determining the Current State of Scientific Evidence]. 2017. Available online: https://www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/Publikationen/Berichte/Psychische-Gesundheit.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=14 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Joint German Occupational Safety and Health Strategy (GDA). Occupational Safety and Health in Practice. Recommendations of the Institutions of the Joint German Occupational Safety and Health Strategy (GDA) for Implementing Psychosocial Risk Assessment. 2014. Available online: https://www.gda-psyche.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/EN/Recommendations%20for%20implementing%20psychosocial%20risk%20assessment.pdf;jsessionid=7D497982756EF128B5A8C9B41E249532?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. The OSH Framework Directive. 2021. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/legislation/directives/the-osh-framework-directive/the-osh-framework-directive-introduction (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Gesetz über die Durchführung von Maßnahmen des Arbeitsschutzes zur Verbesserung der Sicherheit und des Gesundheitsschutzes der Beschäftigten bei der Arbeit (Arbeitsschutzgesetz) [Act on the Implementation of Occupational Health and Safety Measures to Improve the Safety and Health of Employees at Work (Occupational Health and Safety Act)]. ArbSchG. 1996. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/arbschg/BJNR124610996.html (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Badura, B.; Ritter, W.; Scherf, M. Betriebliches Gesundheitsmanagement—Ein Leitfaden für die Praxis [Occupational Health Management—A Guide for Practice]; Sigma, Ed.; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG: Baden-Baden, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry of Health. Das Präventionsgesetz [The Prevention Act]. 2022. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/begriffe-von-a-z/p/praeventionsgesetz.html (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Hoge, A.; Ehmann, A.; Rieger, M.; Siegel, A. Caring for Workers’ Health: Do German Employers Follow a Comprehensive Approach Similar to the Total Worker Health Concept? Results of a Survey in an Economically Powerful Region in Germany. IJERPH 2019, 16, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beck, D.; Schnabel, P.-E. Verbreitung und Inanspruchnahme von Maßnahmen zur Gesundheitsförderung in Betrieben in Deutschland [Prevalence and Utilisation of Health Promotion in German Enterprises]. Gesundheitswesen 2010, 72, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelfel, R.C.; Alles, T.; Weber, A. Gesundheitsmanagement in kleinen und mittleren Unternehmen—Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Unternehmensbefragung [Health Management in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises—Results of a Representative Survey]. Gesundheitswesen 2011, 73, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, D.; Lenhardt, U. Consideration of psychosocial factors in workplace risk assessments: Findings from a company survey in Germany. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- European Commission. User Guide to the SME Definition. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/conferences/state-aid/sme/smedefinitionguide_en.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Siegel, A.; Hoge, A.C.; Ehmann, A.T.; Martus, P.; Rieger, M.A. Attitudes of Company Executives toward a Comprehensive Workplace Health Management-Results of an Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, G. Future Challenges for Work-Related Health Promotion in Europe: A Data-Based Theoretical Reflection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, T.R.; Sinclair, R.; Schulte, P. Better understanding the small business construct to advance research on delivering workplace health and safety. Small Enterp. Res. 2014, 21, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Executive Summary—Management of Psychosocial Risks in European Workplaces: Evidence from the Second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER-2). 2018. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/executive-summary-management-psychosocial-risks-european-workplaces-evidence-second/view (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Cocker, F.; Martin, A.; Scott, J.; Venn, A.; Sanderson, K. Psychological distress, related work attendance, and productivity loss in small-to-medium enterprise owner/managers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 5062–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, S.; Martin, A.; Kilpatrick, M.; Scott, J. Reasons for Engagement: SME Owner-Manager Motivations for Engaging in a Workplace Mental Health and Wellbeing Intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Kilpatrick, M.; Scott, J.; Cocker, F.; Dawkins, S.; Brough, P.; Sanderson, K. Protecting the Mental Health of Small-to-Medium Enterprise Owners: A Randomized Control Trial Evaluating a Self-Administered Versus Telephone Supported Intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.A.M.; Schwarz, E.; Azad, Z.R.; Gritzka, S.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Diebig, M.; Gast, M.; Kilian, R.; Nater, U.; Jarczok, M.; et al. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a stress management training for leaders of small and medium sized enterprises—Study protocol for a randomized controlled-trial. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 468. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, L.; Engels, J.; Kuske, J.; Pavlista, V.; Wulf, I.C. Gemeinsame Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Medizinische Soziologie (DGMS) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Sozialmedizin und Prävention (DGSMP)—Die Gemeinsame Jahrestagung in Düsseldorf Findet Statt unter Beteiligung des MDK Nordrhein und des MDS; Georg Thieme Verlag KG: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlista, V.; Angerer, P.; Diebig, M. Barriers and drivers of psychosocial risk assessments in German micro and small-sized enterprises: A qualitative study with owners and managers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, B.; Medina, J.C.; Gardoki-Souto, I.; Serbanescu, I.; Moreno-Alcázar, A.; Cerga-Pashoja, A.; Coppens, E.; Tóth, M.D.; Fanaj, N.; Greiner, B.A.; et al. Workplace interventions to reduce depression and anxiety in small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weltermann, B.M.; Kersting, C.; Pieper, C.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Dreher, A.; Linden, K.; Rind, E.; Ose, C.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Junne, F.; et al. IMPROVEjob—Participatory intervention to improve job satisfaction of general practice teams: A model for structural and behavioural prevention in small and medium-sized enterprises—A study protocol of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rind, E.; Rieger, M.A.; Jöckel, K.H.; Werners, B.; Junne, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Pieper, C.; Brinkmann, M.; Kasten, S.; Weltermann, B. IMPROVEjob: Reduktion psychischer Belastungen in kleineren Unternehmen [IMPROVEjob: Prevention of work-related psychological stress in small businesses]. Public Health Forum 2020, 28, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rind, E.; Emerich, S.; Preiser, C.; Tsarouha, E.; Rieger, M.A. Exploring Drivers of Work-Related Stress in General Practice Teams as an Example for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Protocol for an Integrated Ethnographic Approach of Social Research Methods. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e15809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Preiser, C.; Tsarouha, E.; Weltermann, B.; Junne, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Hartmann, S.; Bleckwenn, M.; Rieger, M.A.; Rind, E.; On behalf of the IMPROVEjob-Consortium. Psychosocial demands and resources for working time organization in GP practices. Results from a team-based ethnographic study in Germany. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouha, E.; Preiser, C.; Weltermann, B.; Junne, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Stuber, F.; Hartmann, S.; Wittich, A.; Rieger, M.A.; Rind, E. Work-Related Psychosocial Demands and Resources in General Practice Teams in Germany. A Team-Based Ethnography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, L.; Linden, K.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Werners, B.; Grot, M.; Rind, E.; Pieper, C.; Eilerts, A.-L.; Schroeder, V.; Kasten, S.; et al. Job Satisfaction and Chronic Stress of General Practitioners and Their Teams: Baseline Data of a Cluster-Randomised Trial (IMPROVEjob). IJERPH 2021, 18, 9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, L.; Göbel, J.; Minder, K.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Werners, B.; Grot, M.; Rind, E.; Pieper, C.; Eilerts, A.-L.; Schröder, V.; et al. Leadership program with skills training for general practitioners was highly accepted without improving job satisfaction: The cluster randomized IMPROVEjob study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMPROVEjob. Materialien zum Download [Downloads Material]. 2022. Available online: https://www.improvejob.de/de/veroeffentlichungen/materialien-zum-download/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rind, E. Unterstützung von Arbeits- und Gesundheitsschutz in der Hausarztpraxis [Supporting Occupational Health and Safety in the GP Practice]. Available online: https://www.ffas.de/assets/symposium/ABSTRACTS-VORTRAeGE-36.-FreibSymp-Stand-04-2022.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- European Network for Workplace Health Promotion. Cardiff Memorandum on Workplace Health Promotion in Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. 1998. Available online: https://www.enwhp.org/resources/toolip/doc/2018/05/09/cardiff_memorandum_englisch.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Lutz, R.; Fischmann, W.; Drexler, H.; Nöhammer, E. A German Model Project for Workplace Health Promotion-Flow of Communication, Information, and Reasons for Non-Participation in the Offered Measures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkbox. The 2020 UK Workplace Stress Survey. 2022. Available online: https://www.perkbox.com/uk/resources/library/2020-workplace-stress-survey (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Macassa, G.; McGrath, C.; Tomaselli, G.; Buttigieg, S.C. Corporate social responsibility and internal stakeholders’ health and well-being in Europe: A systematic descriptive review. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 866–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehnl, A.; Rehfuess, E.; von Elm, E.; Nowak, D.; Glaser, J. Human resource management training of supervisors for improving health and well-being of employees. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD010905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components | Aim |

|---|---|

| Workshop 1 (leaders only) | Addresses topics around leadership (leadership styles, leadership role conflicts, reflection opportunities, aspects of occupational health, and team care) targeting physicians with leadership responsibilities |

| Workshop 2 (leaders with teams) | Addresses topics around team communication, work organization, and work process, targeting physicians with leadership responsibilities and all practice employees; here, the teams decided which topics they wanted to work on over the course of the implementation period (9 months) to reduce psychosocial stress |

| Toolbox with supplemental material (for leaders and teams) | Supplemental material to consolidate the contents of the workshops afterwards (management logbook for physicians, logbook for practice staff, desk calendar for practice staff, additional material for download in a secured webspace) |

| IMPROVEjob facilitators during a 9-month implementation period | Continuous accompaniment and support of the implementation period by on-site meetings and phone calls |

| Job Satisfaction | Leadership | Teamwork and Relationships | Work Organization and Work Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drivers for promotion | Highlight individual performances within entire team (interview 1) Free scope for decision-making and time management (interview 1) Few controls (interview 1) Individually tailored work assignments (no under- or overstraining) (interview 1) Deployment according to preferences and potential (interviews 1–3) Expression of constructive criticism (Interview 2–3) and work-related requests (Interview 2) Consideration of personal life circumstances (interviews 3–4) High level of identification with company, product, customers, superiors (interview 5) Good working environment (interview 5) Personal contribution to the company’s success (interview 5) Constructive communication and leadership (interview 5) | Leadership as a “collective task” (interviews 1–3, interview 5) Promote cooperation and atmosphere in teams (interviews 2–3) Create good working conditions, foster employee health, ensure consistent compliance with occupational health and safety measures, and quality management (interviews 2–4) Promote professional development and training, and continuously work on changes in attitudes, behaviors, and experiences (interviews 2–3, interview 5) Workshops and individual coaching for managers (interview 5) Influence on sufficient time of employees to complete their work tasks (interview 1) Exchange and reflection with other leaders (interview 5) | Good exchange and clarification of unpleasant issues (interview 1) Definition/identification of common goals (interview 3) Team is responsible for something (e.g., project, task, customer), knows objective and own area of responsibility, as well as contribution to team performance (interview 1, interview 5) Actions to get to know each other better (interview 1) Consideration of suitability for team when selecting new employees (interview 1) Supporting exchange and joint activities (interview 1) | Sufficient communication, precise assignment of tasks and work description per order (interview 1) Clear responsibilities, clearly defined work tasks, coordinated customer assignment (interviews 1–3) Efficient project and schedule management (order acceptance, deadlines) (interviews 2–4) Short decision-making paths (interview 2) Process documentation: how do processes run (interview 5) |

| How to raise interest and contact different MSE/SME settings |

|

| Methodical facilitators to implement relevant topics in MSE/SME settings |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wagner, A.; Werners, B.; Pieper, C.; Eilerts, A.-L.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Grot, M.; Junne, F.; Weltermann, B.M.; Rieger, M.A.; Rind, E., on behalf of the IMPROVEjob-Consortium. Exploring Transfer Potentials of the IMPROVEjob Intervention for Strengthening Workplace Health Management in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Germany: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054067

Wagner A, Werners B, Pieper C, Eilerts A-L, Seifried-Dübon T, Grot M, Junne F, Weltermann BM, Rieger MA, Rind E on behalf of the IMPROVEjob-Consortium. Exploring Transfer Potentials of the IMPROVEjob Intervention for Strengthening Workplace Health Management in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Germany: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054067

Chicago/Turabian StyleWagner, Anke, Brigitte Werners, Claudia Pieper, Anna-Lisa Eilerts, Tanja Seifried-Dübon, Matthias Grot, Florian Junne, Birgitta M. Weltermann, Monika A. Rieger, and Esther Rind on behalf of the IMPROVEjob-Consortium. 2023. "Exploring Transfer Potentials of the IMPROVEjob Intervention for Strengthening Workplace Health Management in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Germany: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054067