Determinants of Deteriorated Self-Perceived Health Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

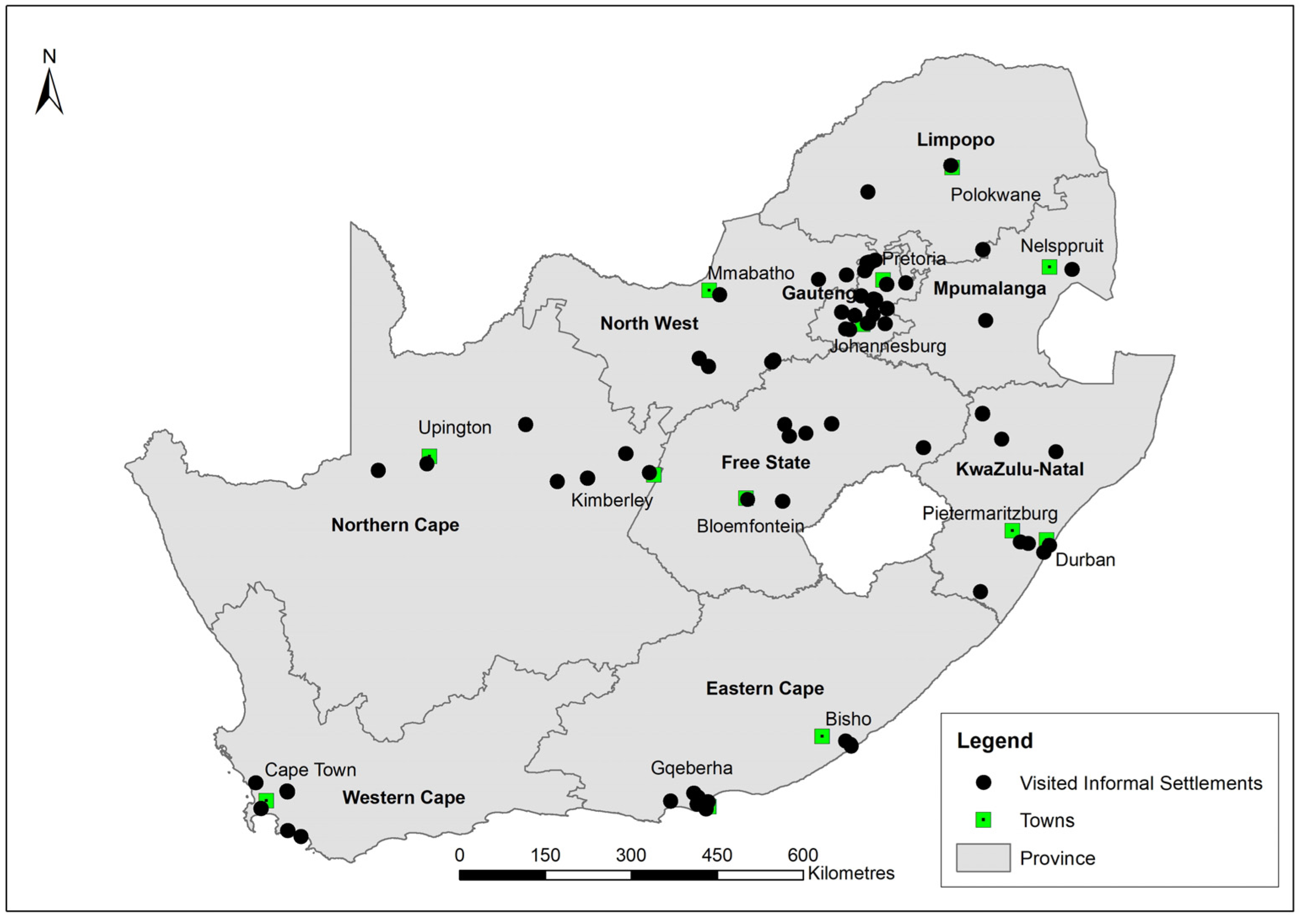

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Deteriorated SPH Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers

3.3. Factors Influencing Deteriorated SPH Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Visual Materials of Informal Settlements in South Africa

Appendix B

| Asset | Response | n |

|---|---|---|

| Hot running water | No | 2240 |

| Yes | 48 | |

| Fridge | No | 1404 |

| Yes | 900 | |

| Deep freezer | No | 2095 |

| Yes | 225 | |

| Domestic servant | No | 2263 |

| Yes | 27 | |

| VCR/DVD | No | 1550 |

| Yes | 622 | |

| Vacuum cleaner | No | 2220 |

| Yes | 90 | |

| Cell phone | No | 669 |

| Yes | 1662 | |

| Washing machine | No | 2078 |

| Yes | 243 | |

| Computer | No | 2223 |

| Yes | 95 | |

| Internet access | No | 2205 |

| Yes | 110 | |

| Electric/gas stove without oven | No | 1440 |

| Yes | 877 | |

| TV | No | 1302 |

| Yes | 1028 | |

| Tumble dryer | No | 2263 |

| Yes | 51 | |

| Telephone | No | 2279 |

| Yes | 28 | |

| Radio | No | 1690 |

| Yes | 632 | |

| HI/FI Music | No | 2126 |

| Yes | 184 | |

| Built in kitchen | No | 2234 |

| Yes | 73 | |

| Home security service | No | 2294 |

| Yes | 13 | |

| Microwave oven | No | 1917 |

| Yes | 404 | |

| M-NET/DSTV | No | 2139 |

| Yes | 177 | |

| Dishwashing machine | No | 2298 |

| Yes | 15 | |

| Sewing machine | No | 2274 |

| Yes | 37 | |

| Car | No | 2132 |

| Yes | 179 | |

| Iron | No | 1153 |

| Yes | 1169 | |

| Electric/gas stove with oven | No | 1901 |

| Yes | 411 | |

| Water tank | No | 2278 |

| Yes | 37 | |

| Power generator | No | 2266 |

| Yes | 47 | |

| Fan | No | 2158 |

| Yes | 151 | |

| Mattress | No | 473 |

| Yes | 1874 | |

| Bicycle | No | 2146 |

| Yes | 164 | |

| Motorcycle/scooter | No | 2297 |

| Yes | 13 | |

| Truck | No | 2304 |

| Yes | 6 | |

| Cart | No | 2295 |

| Yes | 11 | |

| Animals | No | 2209 |

| Yes | 95 | |

| Tools | No | 1635 |

| Yes | 649 |

References

- Zerbo, A.; Delgado, R.C.; González, P.A. Vulnerability and everyday health risks of urban informal settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Glob. Health 2020, 4, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, A.; Oni, T. A systematised review of the health impact of urban informal settlements and implications for upgrading interventions in South Africa, a rapidly urbanising middle-income country. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2019, 16, 3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndinda, C.; Ndhlovu, T.P. Attitudes towards foreigners in informal settlements targeted for upgrading in South Africa: A gendered perspective. Agenda 2016, 30, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndinda, C.; Hongoro, C.; Labadarios, D.; Mokhele, T.; Khalema, E.; Weir-Smith, G.; Sobane, K. Status of informal settlements targeted for upgrading implications for policy and practice. HSRC Rev. 2017, 15, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sverdlik, A. Ill-health and poverty: A literature review on health in informal settlements. Environ. Urban. 2011, 23, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnan, P.; Maharaj, B. Against the odds: Health care in an informal settlement in Durban. Dev. S. Afr. 2000, 17, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Habitat III Issue Paper 22—Informal Settlements; UN-Habitat: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Collantes, C.F. “Unforgotten” informal communities and the COVID-19 pandemic: Sitio San Roque under Metro Manila’s lockdown. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2021, 14, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadifar, M.; Saran, M.; Behzadifar, M.; Martini, M.; Bragazzi, N.L. The ‘Health Transformation Plan’ in Iran: A policy to achieve universal health coverage in slums and informal settlement areas. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2021, 36, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndinda, C.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Juma, P.; Asiki, G.; Kyobutungi, C. Evolution of NCD policies in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; Yan, X.; He, J. The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burström, B.; Fredlund, P. Self rated health: Is it as good a predictor of subsequent mortality among adults in lower as well as in higher social classes? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 55, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.A.; Goldberg, D.E.; Everson, S.A.; Cohen, R.D.; Salonen, R.; Tuomilehto, J.; Salonen, J. Perceived health status and morbidity and mortality: Evidence from the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 25, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, L.; Kristensen, T.S.; Hollnagel, H. Self rated health as a predictor of coronary heart disease in Copenhagen, Denmark. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 1996, 50, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miilunpalo, S.; Vuori, I.; Oja, P.; Pasanen, M.; Urponen, H. Self-rated health status as a health measure: The predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Interview Surveys: Towards International Harmonization of Methods and Instruments; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996.

- Ho, S.Y.; Mak, K.K.; Thomas, G.N.; Schooling, M.; Fielding, R.; Janus, E.D.; Lam, T.H. The relation of chronic cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus to perceived health, and the moderating effects of sex and age. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piko, B.; Barabás, K.; Boda, K. Frequency of common psychosomatic symptoms and its influence on self-perceived health in a Hungarian student population. Eur. J. Public Health 1997, 7, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B. Health-related predictors of self-perceived health in a student population: The importance of physical activity. J. Community Health 2000, 25, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cau, B.M.; Falcão, J.; Arnaldo, C. Determinants of poor self-rated health among adults in urban Mozambique. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboreime-Oikeh, O.; Otiene, G.; Okumbe, G. Determinants of inequalities in self-perceived health among the urban poor in Kenya: A gender perspective. Glob. J. Med. Public Health 2016, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, M.; Shooshtari, S. Determinants of self-perceived health. Health Rep. 2001, 13, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Govender, T.; Barnes, J.M.; Pieper, C.H. Living in low-cost housing settlements in Cape Town, South Africa—The epidemiological characteristics associated with increased health vulnerability. J. Urban Health 2010, 87, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortt, N.K.; Hammett, D. Housing and health in an informal settlement upgrade in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Hous. Built. Environ. 2013, 28, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni, S.; Hongoro, C.; Ndinda, C.; Wisdom, J.P. Assessment of the multi-sectoral approach to tobacco control policies in South Africa and Togo. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, J.; Kruger, H.; Huisman, H.; Wissing, M.; Margetts, B.; Venter, C.; Vorster, H. An epidemiological study of hypertension and its determinants in a population in transition: The THUSA study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2000, 14, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collishaw, S.; Gardner, F.; Aber, J.L.; Cluver, L. Predictors of mental health resilience in children who have been parentally bereaved by AIDS in urban South Africa. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wet, T.; Plagerson, S.; Harpham, T.; Mathee, A. Poor housing, good health: A comparison of formal and informal housing in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasenda, S.; Meland, E.; Hetlevik, Ø.; Thomas Mildestvedt, T.; Dullie, L. Factors associated with self-rated health in primary care in the South-Western health zone of Malawi. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlangeni, L.; Mabaso, M.; Makola, L.; Zuma, K. Predictors of poor self-rated health in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Insights from a cross-sectional survey. Open Public Health J. 2019, 12, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Q.A.; Culbreth, R.E.; Kasirye, R.; Kebede, S.; Bitarabeho, J.; Swahn, M.H. Self-rated physical health, health-risk behaviors, and disparities: A cross-sectional study of youth in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. Glob. Public Health 2022, 17, 2962–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Ndinda, C.; Hongoro, C.; Labadarios, D.; Mokhele, T.; Khalema, E.; Weir-Smith, G.; Douglas, M.; Ngandu, S.; Parker, W.; Tshitangano, F.; et al. A Baseline Assessment for Future Impact Evaluation for Informal Settlements Targeted for Upgrading: Study Report; Department of Human Settlements and Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016; ISBN 978-0-6398286-4-0.

- Chola, L.; Alaba, O. Association of neighbourhood and individual social capital, neighbourhood economic deprivation and self-rated health in South Africa—A multi-level analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Chaparro, J.M.; Zapata-Ossa, H.J.; Cubides-Munévar, A.M.; Curcio, C.L.; Villegas, J.D.; Reyes-Ortiz, C.A. Prevalence of poor self-rated health and associated risk factors among older adults in Cali, Colombia. Colomb. Med. 2013, 44, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-Roncancio, M.; González-Uribe, C.; Lucumí, D.I. Do the determinants of self-rated health vary among older people with disability, chronic diseases or both conditions in urban Colombia? Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00041719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höfelmann, D.A.; Garcia, L.P.; de Freitas, L.R.S. Self-rated health in Brazilian adults and elderly: Data from the National Household Sample Survey 2008. Salud Publica Mex. 2014, 56, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; Stata Corp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Ngadan, D.P.; Arif, M.T. Factors affecting satisfaction on antenatal care services in Sarawak, Malaysia: Evidence from a cross sectional study. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, A.; Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Fischer, F. Patient satisfaction with doctor-patient interactions: A mixed methods study among diabetes mellitus patients in Pakistan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewpaul, R.; Mabaso, M.; Dukhi, N.; Naidoo, I.; Vondo, N.; Davids, A.; Mokhele, T.; Reddy, P. Determinants of social distancing among South Africans from twelve days into the COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutyambizi, C.; Mokhele, T.; Ndinda, C.; Hongoro, C. Access to and satisfaction with basic services in informal settlements: Results from a baseline assessment survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, W.I.A.; Weiler, R.; Orisatoki, R.; Lu, X.; Andkhoie, M.; Ramsay, D.; Yaghoubi, M.; Steeves, M.; Szafron, M.; Farag, M. Determinants of self-perceived health for Canadians aged 40 and older and policy implications. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Chen, L.J.; Huang, S.T.; Meng, L.C.; Lee, W.J.; Peng, L.N.; Hsiao, F.Y.; Chen, L.K. Age and sex differences in associations between self-reported health, physical function, mental function and mortality. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 98, 104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, J.; Ruigomez, A.; Pastor, V.; Martin-Moreno, J.M. Determinants of self assessed health among Spanish older people living at home. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1999, 53, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.Y.; Peters, J.L.; Levy, J.I.; Bongiovanni, R.; Rossini, A.; Scammell, M.K. Self-rated health and its association with perceived environmental hazards, the social environment, and cultural stressors in an environmental justice population. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo-Velásquez, B.; Restrepo-Méndez, M.C. The role of individual, household and area of residence factors on poor self-rated health in Colombian adults: A multilevel study. Biomedica 2020, 40, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatti, L.; Barreto, S.M.; César, C.C. Unemployment and self-rated health: Neighborhood influence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosholm, J.U.; Christensen, K. Relationship between drug use and self-reported health in elderly Danes. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1997, 53, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, P.M.; Canham, S.L.; Martins, S.S.; Spira, A.P. Substance-use coping and self-rated health among US middle-aged and older adults. Addict. Behav. 2015, 42, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, S.; Amiel, S.A.; Rogers, H.; Choudhary, P.; Cox, A.; de Zoysa, N.; Hopkins, D.; Forbes, A. Poorer glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes is associated with reduced self-management and poorer perceived health: P cross-sectional study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.Y.E.; Almeida, O.P.; McCaul, K.A.; Yeap, B.B.; Hankey, G.J.; van Bockxmeer, F.M.; Flicker, L. Elevated homocysteine is associated with poorer self-perceived physical health in older men: The health in men study. Maturitas 2012, 73, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Chhetri, J.K.; Ji, S.; Ma, L.; Dan, X.; Chan, P. Poor self-perceived health is associated with frailty and prefrailty in urban living older adults: A cross-sectional analysis. Geriatr. Nurs. Minneap. 2020, 41, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadiri, C.P.; Gisinger, T.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Kublickiene, K.; Herrero, M.T.; Norris, C.M.; Raparelli, V.; Pilote, L. Determinants of perceived health and unmet healthcare needs in universal healthcare systems with high gender equality. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, A.L.; Xavier, C.C.; de Souza Andrade, A.C.; de Lima Friche, A.A.; Proietti, F.A.; Caiaffa, W.T. Self-rated health in urban adults, perceptions of the physical and social environment, and reported comorbidities: The BH health study. Cad. Saúde Pública 2015, 31, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | % | 95%CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2242 | 100 | ||

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1095 | 54.5 | [47.8–61.0] | 0.489 |

| Female | 1018 | 45.5 | [39.0–52.2] | |

| Age group | ||||

| 18 to 29 | 305 | 14.6 | [11.0–19.1] | 0.066 |

| 30 to 39 | 600 | 29.8 | [25.4–34.7] | |

| 40 to 49 | 551 | 26.1 | [23.5–28.9] | |

| 50 to 59 | 373 | 18.4 | [14.5–23.0] | |

| 60+ | 277 | 11.1 | [7.5–16.3] | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1049 | 48.1 | [44.6–51.6] | 0.191 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 250 | 8.1 | [6.2–10.4] | |

| Single/never married | 895 | 43.8 | [40.0–47.8] | |

| Socio-economic factors | ||||

| Education level | ||||

| No/Primary school | 871 | 36.9 | [33.4–40.6] | 0.03 |

| Secondary school | 823 | 36.7 | [33.3–40.3] | |

| Matric/Higher | 507 | 26.4 | [22.9–30.1] | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1346 | 60 | [56.1–63.8] | 0.623 |

| Employed | 853 | 40 | [36.2–43.9] | |

| Household income | ||||

| R0-R2 000 | 1138 | 58.9 | [50.0–67.3] | 0.389 |

| R2 001-R5 500 | 716 | 32.8 | [26.3–40.0] | |

| R5 501 and more | 149 | 8.3 | [6.2–11.0] | |

| Ever ran out of food | ||||

| Never | 648 | 31.8 | [27.3–36.6] | 0.009 |

| Sometimes | 1271 | 52.9 | [49.6–56.2] | |

| Always | 281 | 15.3 | [10.0–22.8] | |

| Living Standard Measure | ||||

| Low | 723 | 32.1 | [23.8–41.7] | 0.131 |

| Medium | 725 | 34.3 | [31.0–37.8] | |

| High | 783 | 33.6 | [25.5–42.7] | |

| Health and behavioural factors | ||||

| Illness or injury | ||||

| No | 1663 | 77.6 | [20.2–24.8] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 536 | 22.4 | [75.2–79.8] | |

| Smoke | ||||

| No | 1397 | 68.4 | [65.2–71.5] | 0.321 |

| Yes | 813 | 31.6 | [28.5–34.8] | |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| No | 1441 | 69.2 | [66.9–71.4] | 0.644 |

| Yes | 754 | 30.8 | [28.6–33.1] | |

| Drug use | ||||

| No | 2046 | 95.5 | [94.3–96.5] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 109 | 4.5 | [3.5–5.7] |

| Sample | %(n) | 95%CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1095 | 13.9(152) | [10.5–18.1] | 0.494 |

| Female | 1018 | 15.8(161) | [12.2–20.1] | |

| Age group | ||||

| 18 to 29 | 305 | 13.5(41) | [7.3–23.5] | 0.096 |

| 30 to 39 | 600 | 10.6(64) | [7.2–15.4] | |

| 40 to 49 | 551 | 14.7(81) | [10.1–20.9] | |

| 50 to 59 | 373 | 21.3(79) | [14.9–29.6] | |

| 277 | 17.9(50) | [13.0–24.1] | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1049 | 13.4(141) | [10.1–17.4] | 0.347 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 250 | 19.0(48) | [12.9–27.1] | |

| Single/never married | 895 | 16.0(143) | [12.0–21.0] | |

| Socio-economic factors | ||||

| Education level | ||||

| No/primary school | 871 | 19.6(171) | [15.2–25.0] | <0.05 |

| Secondary school | 823 | 12.8(105) | [9.2–17.7] | |

| Matric/higher | 507 | 10.3(52) | [6.9–15.3] | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1346 | 15.8(213) | [12.7–19.5] | 0.507 |

| Employed | 853 | 13.9(119) | [10.1–18.9] | |

| Household income | ||||

| R0-R2000 | 1138 | 15.0(171) | [11.7–19.0] | 0.431 |

| R2001-R5500 | 716 | 15.7(112) | [11.4–21.3] | |

| R5501 and more | 149 | 8.2(12) | [2.7–22.2] | |

| Ever ran out of food | ||||

| Never | 648 | 10.0(65) | [6.8–14.5] | <0.05 |

| Sometimes | 1271 | 16.3(207) | [13.1–20.1] | |

| Always | 281 | 21.9(62) | [13.8–32.9] | |

| Living Standard Measure | ||||

| Low | 723 | 14.3(103) | [10.2–19.7] | 0.133 |

| Medium | 725 | 18.3(133) | [13.6–24.2] | |

| High | 783 | 11.9(93) | [8.9–15.9] | |

| Health and behavioural factors | ||||

| Illness or injury | ||||

| No | 1663 | 11.4(190) | [8.9–14.5] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 536 | 27.1(145) | [20.9–34.2] | |

| Smoke | ||||

| No | 1397 | 14.1(197) | [11.3–17.6] | 0.359 |

| Yes | 813 | 16.8(137) | [12.4–22.5] | |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| No | 1441 | 15.2(219) | [12.2–18.8] | 0.479 |

| Yes | 754 | 13.2(100) | [9.5–18.1] | |

| Drug use | ||||

| No | 2046 | 15.3(313) | [12.7–18.2] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 109 | 1.4(2) | [0.5–3.8] |

| Odds Ratio | [95%CI] | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | |||

| Female | 1.308 | [0.755–2.265] | 0.338 |

| Age group | |||

| 18 to 29 (ref) | |||

| 30 to 39 | 0.332 | [0.131–0.840] | <0.05 |

| 40 to 49 | 0.716 | [0.231–2.218] | 0.562 |

| 50 to 59 | 0.909 | [0.307–2.695] | 0.864 |

| 60+ | 1.158 | [0.363–3.690] | 0.804 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting (ref) | |||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 0.794 | [0.370–1.704] | 0.553 |

| Single/never married | 1.116 | [0.607–2.053] | 0.725 |

| Socio-economic factors | |||

| Education level | |||

| No/primary school (ref) | |||

| Secondary school | 0.682 | [0.308–1.508] | 0.344 |

| Matric/higher | 0.905 | [0.415–1.974] | 0.802 |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed (ref) | |||

| Employed | 1.739 | [0.984–3.074] | 0.057 |

| Household income | |||

| R0-R2000 (ref) | |||

| R2 001-R5500 | 1.132 | [0.609–2.105] | 0.694 |

| R5501 and more | 0.365 | [0.144–0.922] | <0.05 |

| Ever ran out of food | |||

| Never (ref) | |||

| Sometimes | 1.840 | [0.979–3.458] | 0.058 |

| Always | 3.120 | [1.258–7.737] | <0.05 |

| Living Standard Measure | |||

| Low (ref) | |||

| Medium | 1.179 | [0.593–2.342] | 0.638 |

| High | 0.813 | [0.369–1.793] | 0.608 |

| Health and behavioural factors | |||

| Illness or injury | |||

| No (ref) | |||

| Yes | 3.645 | [2.147–6.186] | <0.001 |

| Smoke | |||

| No (ref) | |||

| Yes | 1.155 | [0.605–2.203] | 0.662 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| No (ref) | |||

| Yes | 1.172 | [0.614–2.237] | 0.629 |

| Drug use | |||

| No (ref) | |||

| Yes | 0.069 | [0.020–0.240] | <0.001 |

| Model 1—Better as Base Category | Model 2—Neutral as Base Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | [95%CI] | p Value | OR | [95%CI] | p Value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (ref) | ||||||

| Female | 1.339 | [0.766–2.341] | 0.301 | 1.257 | [0.772–2.047] | 0.352 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18 to 29 (ref) | ||||||

| 30 to 39 | 0.367 | [0.161–0.838] | 0.018 | 0.29 | [0.086–0.978] | 0.046 |

| 40 to 49 | 0.832 | [0.279–2.481] | 0.737 | 0.595 | [0.164–2.167] | 0.426 |

| 50 to 59 | 1.107 | [0.433–2.830] | 0.83 | 0.725 | [0.205–2.559] | 0.612 |

| 60+ | 1.378 | [0.513–3.699] | 0.519 | 0.934 | [0.308–2.837] | 0.903 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting (ref) | ||||||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 0.871 | [0.434–1.748] | 0.693 | 0.73 | [0.408–1.306] | 0.284 |

| Single/never married | 1.104 | [0.847–1.439] | 0.457 | 1.124 | [0.650–1.945] | 0.671 |

| Socio-economic factors | ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| No/primary school (ref) | ||||||

| Secondary school | 0.726 | [0.402–1.312] | 0.284 | 0.638 | [0.374–1.087] | 0.097 |

| Matric/higher | 1.045 | [0.356–3.069] | 0.935 | 0.771 | [0.217–2.737] | 0.683 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Unemployed (ref) | ||||||

| Employed | 1.654 | [0.881–3.106] | 0.115 | 1.83 | [1.001–3.347] | 0.05 |

| Household income | ||||||

| R0-R2000 (ref) | ||||||

| R2001-R5500 | 1.368 | [0.592–3.159] | 0.457 | 0.92 | [0.455–1.862] | 0.814 |

| R5501 and more | 0.446 | [0.130–1.533] | 0.196 | 0.296 | [0.078–1.125] | 0.073 |

| Ever an out food | ||||||

| Never (ref) | ||||||

| Sometimes | 1.899 | [1.173–3.076] | 0.01 | 1.785 | [1.108–2.875] | 0.018 |

| Always | 5.168 | [1.563–17.090] | 0.008 | 1.996 | [0.982–4.055] | 0.056 |

| Living Standard Measure | ||||||

| Low (ref) | ||||||

| Medium | 1.11 | [0.628–1.963] | 0.715 | 1.257 | [0.620–2.550] | 0.52 |

| High | 0.759 | [0.273–2.110] | 0.592 | 0.874 | [0.324–2.357] | 0.787 |

| Health and behavioural factors | ||||||

| Illness or injury | ||||||

| No (ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 3.377 | [2.137–5.335] | <0.001 | 3.979 | [2.638–6.002] | <0.001 |

| Smoke | ||||||

| No (ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.215 | [0.843–1.751] | 0.29 | 1.083 | [0.589–1.990] | 0.796 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| No (ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.177 | [0.545–2.542] | 0.673 | 1.174 | [0.588–2.343] | 0.645 |

| Drug use | ||||||

| No (ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.058 | [0.016–0.211] | <0.001 | 0.082 | [0.023–0.289] | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mokhele, T.; Mutyambizi, C.; Manyaapelo, T.; Ngobeni, A.; Ndinda, C.; Hongoro, C. Determinants of Deteriorated Self-Perceived Health Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054174

Mokhele T, Mutyambizi C, Manyaapelo T, Ngobeni A, Ndinda C, Hongoro C. Determinants of Deteriorated Self-Perceived Health Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054174

Chicago/Turabian StyleMokhele, Tholang, Chipo Mutyambizi, Thabang Manyaapelo, Amukelani Ngobeni, Catherine Ndinda, and Charles Hongoro. 2023. "Determinants of Deteriorated Self-Perceived Health Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054174

APA StyleMokhele, T., Mutyambizi, C., Manyaapelo, T., Ngobeni, A., Ndinda, C., & Hongoro, C. (2023). Determinants of Deteriorated Self-Perceived Health Status among Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054174