Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction and Validation of the SeViD Questionnaire

2.2. Design and Conduction of the SeViD-III Survey

2.3. Measurements, Preparation and Re-Coding of Variables for Statistical Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Second Victim Status

3.3. Risks Factors for Becoming a Second Victim

3.4. Factors with Impact on Symptom Load

3.5. Support Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, A.W. Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000, 320, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaecht, K.; Seys, D.; Russotto, S.; Strametz, R.; Mira, J.; Sigurgeirsdóttir, S.; Wu, A.W.; Põlluste, K.; Popovici, D.G.; Sfetcu, R.; et al. An Evidence and Consensus-Based Definition of Second Victim: A Strategic Topic in Healthcare Quality, Patient Safety, Person-Centeredness and Human Resource Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seys, D.; Wu, A.W.; Gerven, E.V.; Vleugels, A.; Euwema, M.; Panella, M.; Scott, S.D.; Conway, J.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: A systematic review. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 36, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, C.; Ratti, M.; Russotto, S.; Seys, D.; Vanhaecht, K.; Panella, M. Healthcare Students and Medical Residents as Second Victims: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrabhatla, T.; Asgedom, H.; Gaudiano, Z.P.; de Avila, L.; Roach, K.L.; Venkatesan, C.; Weinstein, A.A.; Younossi, Z.M. Second victim experiences and moral injury as predictors of hospitalist burnout before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liukka, M.; Steven, A.; Moreno, M.F.V.; Sara-Aho, A.M.; Khakurel, J.; Pearson, P.; Turunen, H.; Tella, S. Action after Adverse Events in Healthcare: An Integrative Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marr, R.; Goyal, A.; Quinn, M.; Chopra, V. Support opportunities for second victims lessons learned: A qualitative study of the top 20 US News and World Report Honor Roll Hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Campagna, I.; Benoni, R.; Tardivo, S.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Promoting the Psychological Well-Being of Healthcare Providers Facing the Burden of Adverse Events: A Systematic Review of Second Victim Support Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrøder, K.; Bovil, T.; Jørgensen, J.S.; Abrahamsen, C. Evaluation of’the Buddy Study’, a peer support program for second victims in healthcare: A survey in two Danish hospital departments. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehman, C.R.; Testo, Z.; Gershaw, R.S.; Kellogg, A.R. Burnout, Drop Out, Suicide: Physician Loss in Emergency Medicine, Part I. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 3, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strametz, R.; Fendel, J.C.; Koch, P.; Roesner, H.; Zilezinski, M.; Bushuven, S.; Raspe, M. Prevalence of second victims, risk factors and support strategies among young German physicians in internal medicine (SeViD-I survey). J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Strametz, R.; Fendel, J.C.; Koch, P.; Roesner, H.; Zilezinski, M.; Bushuven, S.; Raspe, M. Prevalence of Second Victims, Risk Factors, and Support Strategies among German Nurses (SeViD-II Survey). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strametz, R.; Roesner, H.; Abloescher, M.; Huf, W.; Ettl, B.; Raspe, M. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess incidence and reactions of second victims in German speaking countries (SeViD). Zbl. Arbeitsmed. 2021, 71, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Short version of the big five inventory (BFI-K). Diagnostica 2005, 51, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, R.J.; Littell, R.C.; Creighton, L. Regression Using JMP; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara, S.; D’Arcy, F.; Dowling, C.; Walsh, K. The psychological impact of adverse events on urology trainees. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 3, 1–6, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Boyd, C.M.; Dollard, M.; Gillespie, N.; Winefield, A.H.; Stough, C. The role of personality in the job demands-resources model: A study of Australian academic staff. Career Dev. Int. 2010, 15, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, R.M.; Van Vianen, A.E.M.; Bosle, C.; Fischer, J.E. Personality type matters: Perceptions of job demands, job resources, and their associations with work engagement and mental health. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushuven, S.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Bentele, M.; Bentele, S.; Strametz, R.; Klemm, V.; Raspe, M. Self-Assessment and Learning Motivation in the Second Victim Phenomenon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kommission Berufliche Belastung der DGAI [Dealing with severe complications and burdensome operations]. Anaesth Intensiv. 2013, 54, 490–494.

- Wrobel, M.; Armbruster, W.; Graesner, J.T.; Prueckner, S.; Beckers, S.K.; Breuer, G.; Corzillius, M.; Heinrichs, M.; Hoffmann, F.; Hossfeld, B.; et al. Simulation training as part of emergency medical speciality training—Reisensburg declaration on simulation-based practical employment in the scope of the model specialty training regulations for emergency medicine. Anaesth Intensiv. 2017, 58, 274–278. [Google Scholar]

| Total number of fully completed surveys | 401 | |

| Gender (female/male/diverse) | 30.9% (124)/69.1% (277)/- | |

| Age (years) | ≤39 | 35.7% (143) |

| 40–48 | 31.9% (128) | |

| 49–74 | 32.4% (130) | |

| Formal education * | Board-certified EMS physician (current) | 91.2% (369) |

| Board-certified anesthesiologist | 63.6% (255) | |

| Certified EMS physician (obsolete) | 27.2% (102) | |

| Board-certified clinical emergency physician | 12.0% (48) | |

| Anesthesiology resident | 9.7% (39) | |

| Board-certified internist | 9.2% (37) | |

| Board-certified general surgeon/trauma surgeon | 9.0% (36) | |

| Board-certified general practitioner | 4.2% (17) | |

| Other | 13.7% (55) | |

| Professional experience as an EMS physician (years) | Median (min/max) | 11 (1/40) |

| Leading position | 51.4% (206) | |

| Full vs. part time occupation | 68.3 vs. 31.7% | |

| Place of occupation | Operating Room | 55.9% (224) |

| Intensive Care/Intermediate Care | 46.1% (185) | |

| Emergency Department | 22.9% (92) | |

| Registered Practice | 9.0% (36) | |

| General Ward | 4.7 (19) | |

| Other | 21.9% (88) | |

| Working mode (time) | Irregular, no shift work | 39.2% (157) |

| Shift work including nights | 31.9% (128) | |

| Regular, daytime only | 13.5% (54) | |

| Shift work without nights | 3.5% (14) | |

| Other | 11.9% (48) | |

| Months spent in patient care during past year | Mean ± SD | 10.4 ± 4 |

| Openness | Mean ± SD | 3.32 ± 0.97 |

| Conscientiousness | Mean ± SD | 3.99 ± 0.83 |

| Extraversion | Mean ± SD | 3.27 ± 0.97 |

| Agreeableness | Mean ± SD | 3.26 ± 0.78 |

| Neuroticism | Mean ± SD | 2.35 ± 0.86 |

| Independent Variable | Regression Coefficient B with BCa 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio (Exponentiation of the B Coefficient (Exp(B)) | Odds Ratio 95% CI Lower | Odds Ratio 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) 1 | −0.08 BCa 95% CI [−0.55, 0.43] | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.58 | 1.49 |

| Age group 2 ≤ 39 40–48 | 0.16 BCa 95% CI [−0.60, 0.86] 0.83 BCa 95% CI [−0.80, 1.03] | 0.60 0.86 | 1.167 1.09 | 0.66 0.46 | 1.17 1.09 |

| Professional experience as an EMS physician (years) | −0.10 BCa 95% CI [−0.05, 0.03] | 0.61 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 |

| Workplace in acute care 3 | −0.07 BCa 95% CI [−0.59, 0.43] | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.57 | 1.53 |

| Openness to experience | 0.14 BCa 95% CI [−0.11, 0.42] | 0.22 | 1.15 | 0.92 | 1.44 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.03 BCa 95% CI [−0.26, 0.34] | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.79 | 1.35 |

| Extraversion | −0.13 BCa 95% CI [−0.34, 0.05] | 0.22 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 1.09 |

| Agreeableness | 0.30 BCa 95% CI [−0.01, 0.60] | 0.03 | 1.35 | 1.03 | 1.78 |

| Neuroticism | 0.37 BCa 95% CI [0.04, 0.70] | 0.01 | 1.44 | 1.10 | 1.88 |

| Independent Variable | Unstandardized Regression Coefficient B | p | BCa 95% CI Lower | BCa 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.59 | 0.11 | −1.56 | 8.25 |

| Gender (female = 1, male = 2) | −0.70 | 0.09 | −1.87 | 0.20 |

| Age 1 | 2.37 | 0.25 | −1.73 | 9.81 |

| Professional experience as an EMS physician (years) 1 | −1.97 | 0.01 | −3.60 | −0.42 |

| Independent Variable | Unstandardized Regression Coefficient B | p | BCa 95% CI Lower | BCA 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.96 | 0.14 | −1.46 | 11.49 |

| Gender (female = 1, male = 2) | −0.70 | 0.18 | −1.71 | 0.28 |

| Age 1 | 2.37 | 0.43 | −3.36 | 8.82 |

| Professional experience as an EMS physician (years) 1 | −1.57 | 0.05 | −3.29 | −0.01 |

| Openness to experience | 0.01 | 0.99 | −0.55 | 0.51 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.02 | 0.96 | −0.56 | 0.53 |

| Extraversion | −0.49 | 0.04 | −0.91 | −0.08 |

| Agreeableness | 0.22 | 0.52 | −0.38 | 0.86 |

| Neuroticism | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 1.48 |

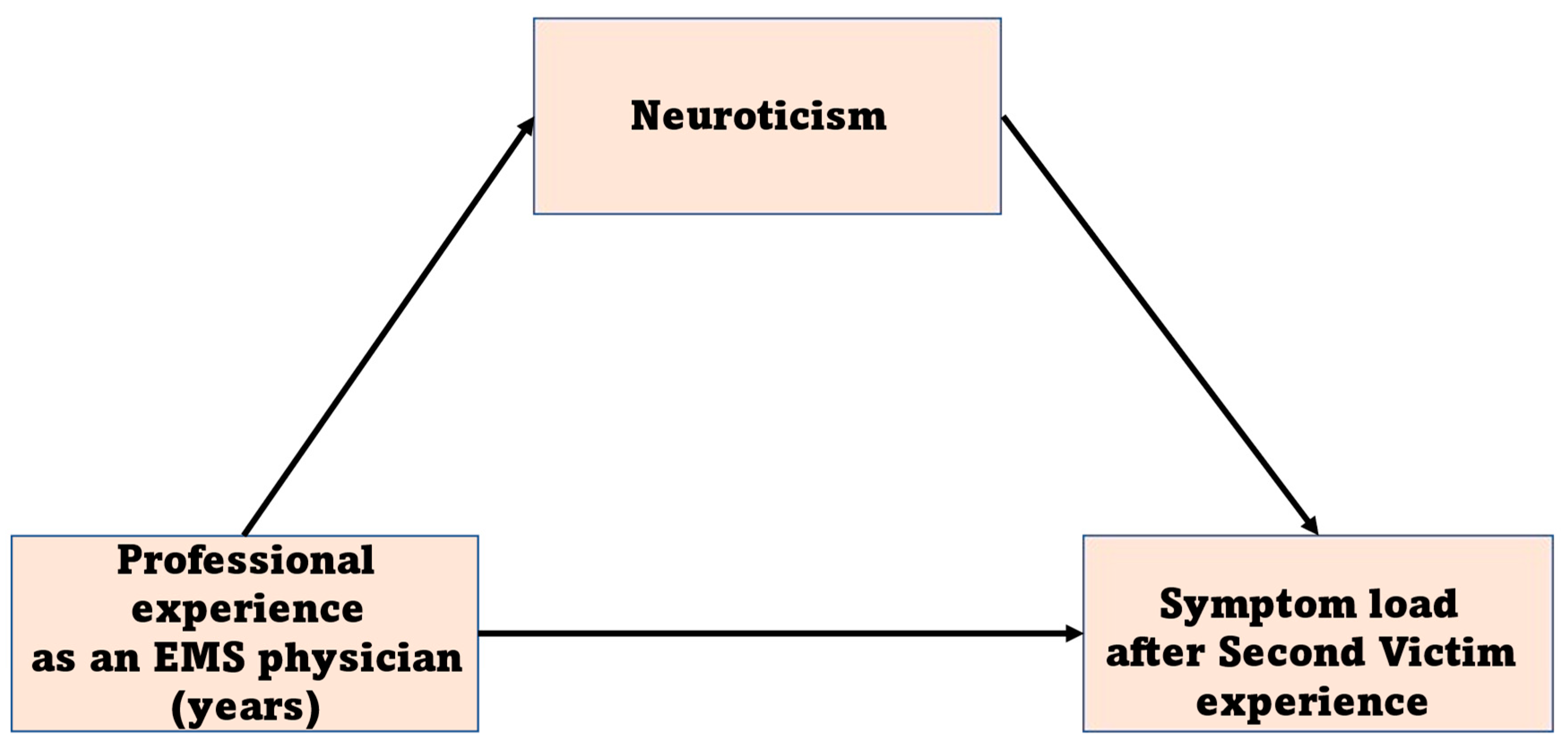

| Relationship | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | 95% CI of Indirect Effect [bootLLCI, bootULCI] | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional experience < Neuroticism < Symptom load | −1.19 | −0.92 | −0.27 | [−0.54, −0.06] | Partial mediation |

| Support Strategy | Rated Rather or very Helpful % (n) * No SV Status (n = 188) | Rated Rather Not or Not Helpful % (n) No SV Status (n = 188) | Rated Rather or very Helpful % (n) SV Status Present (n = 213) | Rated Rather Not or Not Helpful % (n) SV Status Present (n = 213) | p (chi2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Immediate time out to recover | 70.7 (133) | 16.5 (31) | 64.3 (137) | 30.5 (65) | p = 0.001 |

| 2. Access to counseling including psychological/psychiatric services | 87.8 (165) | 7.4 (14) | 83.1 (177) | 11.7 (25) | p = 0.14 |

| 3. Opportunity to discuss emotional and ethical issues | 94.7 (178) | 2.1 (4) | 93.9 (200) | 4.7 (10) | p = 0.17 |

| 4. Concise and prompt information about procedures (e.g., root cause analysis, reporting) | 86.7 (163) | 10.1 (19) | 88.3 (188) | 8.9 (19) | p = 0.67 |

| 5. Formal peer support | 84.0 (158) | 10.1 (19) | 84.0 (179) | 12.7 (27) | p = 0.48 |

| 6. Informal emotional support | 75.7 (140) | 17.6 (33) | 81.2 (173) | 11.3 (24) | p = 0.07 |

| 7. Prompt debriefing/crisis intervention | 91.0 (171) | 5.3 (10) | 90.6 (193) | 7.0 (15) | p = 0.50 |

| 8. Supportive guidance for continuing professional duties | 62.8 (118) | 30.3 (57) | 66.7 (142) | 25.8 (55) | p = 0.29 |

| 9. Support for communicating with patients or relatives | 71.8 (135) | 24.5 (46) | 64.8 (138) | 29.1 (62) | p = 0.23 |

| 10. Specific regulations concerning professional conduct | 59.0 (111) | 34.0 (64) | 57.3 (122) | 29.6 (63) | p = 0.59 |

| 11. Support during active follow up of the incident | 83.5 (157) | 11.7 (22) | 82.6 (176) | 11.3 (24) | p = 0.95 |

| 12. Safe opportunity to contribute insights in order to prevent similar events in the future | 83.5 (157) | 13.3 (25) | 85.9 (183) | 7.5 (16) | p = 0.07 |

| 13. Access to legal counseling after severe events | 94.7 (187) | 3.7 (7) | 88.7 (189) | 5.6 (12) | p = 0.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marung, H.; Strametz, R.; Roesner, H.; Reifferscheid, F.; Petzina, R.; Klemm, V.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Bushuven, S. Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054267

Marung H, Strametz R, Roesner H, Reifferscheid F, Petzina R, Klemm V, Trifunovic-Koenig M, Bushuven S. Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054267

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarung, Hartwig, Reinhard Strametz, Hannah Roesner, Florian Reifferscheid, Rainer Petzina, Victoria Klemm, Milena Trifunovic-Koenig, and Stefan Bushuven. 2023. "Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054267

APA StyleMarung, H., Strametz, R., Roesner, H., Reifferscheid, F., Petzina, R., Klemm, V., Trifunovic-Koenig, M., & Bushuven, S. (2023). Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054267