Narratives of Women and Gender Relations in Chinese COVID-19 Frontline Reports in 2020

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

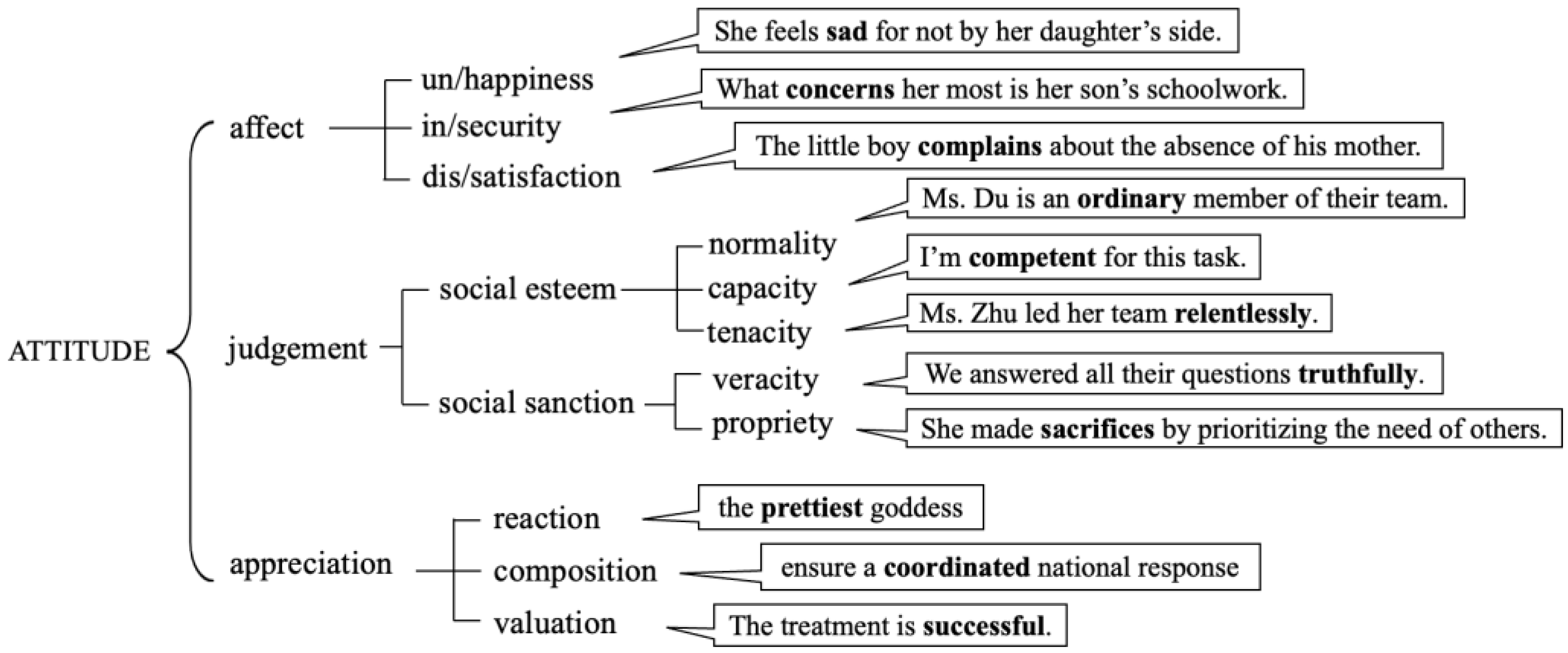

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Data Findings

3.2. Patterns of judgement

3.2.1. Patterns of capacity

- (1)

- The affiliated hospitals of the Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology have devoted more than 33,000 medical staff and 8900 hospital beds, and two renowned affiliated hospitals of Wuhan University have devoted more than 17,000 medical staff and 8600 hospital beds. (CCTV news, http://bitly.ws/A4tS, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (2)

- The eighth batch of medical team from Chongqing to aid Hubei consists of 163 medical staff. It received 83 patients and 67 of them were cured… It’s the “first” one to deploy the ECMO technique, prescribe traditional Chinese medicine apozem, and conduct psychological intervention and respiratory rehabilitation training. (Chongqing Daily, http://bitly.ws/A4zq, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (3)

- In Wuhan, 3047 League members specialized in healthcare displayed courage when placed in harm’s way and held fast to their positions in fever clinics, observation rooms, emergency rooms, intensive care units, and grassroots communities; 2000 Youth League members from 97 commandos in Jiangsu Province provided help for 58 manufacturers and produced more than 1076 masks and 130,000 protective suits; in Xinxiang of Henan Province, eight youth commandos helped 15 key enterprises to produce 1,100,000 masks per day; and in Changxing, Zhejiang Province, 68 League branch secretaries took charge of croplands and aided in the reaping, packaging and delivering of farm products. (China Youth Daily, http://bitly.ws/A4Ez, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (4)

- Among the 42,000 medical staff that have been sent to Hubei Province to fight against the pandemic, 12,000 were Post-90s (born in the 1990s), among which Post-95s (born between 1995 to 1999) and Post-00s (born in the 2000s) accounted for a substantial portion. (China Youth Net, http://bitly.ws/AtVG, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (1)

- Mr. Peng, director of the intensive care unit of Zhongnan Hospital, says ECMO is only for rescue purposes and is not suitable for popularization. This technology is a life support for critically ill patients with cardiopulmonary failure… Head nurse Ms. Ma says beds and protective suits are in short supply. She asks nurses to avoid drinking too much water and reduce the chances of taking the suits off… (China Newsweek, http://bitly.ws/A57R, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (2)

- Mr. Deng, director of the vascular surgery department, remembers the terrifying surgery. Sight and movement were largely restricted due to foggy goggles and the protective suit, but he successfully separated the femoral vein and the femoral artery thanks to extensive experience. (China Youth Daily, http://bitly.ws/A57N, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (3)

- Mr. Gong, head of the medical teams of Dalian Province, remembers that the degree of blood oxygen saturation of a most critical patient was only 39%, in a severe hypoxic condition… Nurses take the hardest work as they keep giving injections, drawing blood, carrying out adjuvant therapy and assisting patients eating, going to the toilet, and disposing of waste. (China National Radio News, http://bitly.ws/A57J, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (4)

- Makeshift hospitals (“Fangcang”) were born following the suggestion of Mr. Wang. He is the dean of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and vice dean of the Chinese Academy of Engineering. … Mr. Wan, vice dean of Hubei General Hospital and dean of the makeshift hospital in Wuchang, guided his team in drawing up the work manual for the makeshift hospitals, which was then adopted by the headquarters and issued to each branch of the makeshift hospitals. (Guangming Daily, http://bitly.ws/A57G, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (5)

- After the advice of the team chiefs, Mr. Chen and Mr. Hu, a series of key measures were implemented, such as quarantine, disinfection, fever clinic and pre-examination triage. … in February, Mr. Hu led other medical workers in the department and was stationed in the East Area. (The Paper, http://bitly.ws/A57E, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

3.2.2. Patterns of tenacity

- (1)

- they (women) take off usual dresses and put on wartime robes (xinhuanet, http://bitly.ws/A6i9, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (2)

- The tender shoulders of women can carry a heavy load. They are as excellent as their male peers…

- (3)

- Women are inherently weak, but they become stronger when fighting against the pandemic. (Xinhua News Agency, http://bitly.ws/A6ia, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (4)

- Ms. Huang, like many other nursing sisters in the rescue, had kinfolk to look after her. But in Wuhan, she becomes a warrior. (People’s Daily, http://bitly.ws/A6ic, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (5)

- What he wrote in the battle request is …young generation should be vigorous, and men should have the courage… (http://bitly.ws/A6ie, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (1)

- In the early days of the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, daily outpatient visits were 10 times those of the past. Ms. Zhu, a nurse from the nursing team of the fever clinic, worked from 2 a.m. to 9 a.m. and did blood sampling for over 200 patients. She sweated in her protective suit profusely but could not take off her gear for long periods of time. Her face was red and swollen afterwards… (Economic Daily, http://bitly.ws/A4Ae, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (2)

- Ms. Huang, who took charge of 3 neighborhoods that consisted of 1831 households as well as 5 hotels, 2 construction sites, and 1 supermarket, had to walk 20,000 steps every day. (CCTV News, http://bitly.ws/A6j6, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (3)

- Mr. Yu, the head of the 21st ward, has worked continuously for 40 days and saved more than 60 critically ill patients with no staff being infected. Even without the help of X-ray radiography machine, he managed to set up the temporary cardiac pacemaker for patients. … Ms. Guo, a nurse from the emergency centre, carried out health care work for more than 10 h a day… helping patients breathe, drink water, have meals, go to the toilet and change their positions in bed…everything worked out, but she was infected unfortunately… She volunteered to go back to the frontline once she recovered from the COVID. (The Paper, http://bitly.ws/A6jq, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (4)

- The first three days at ‘Fangcang’ were the hardest. Chief Mr. Chang and his teammates work day and night to work out the schemes of treatment methods, diagnostic standards and discharge standards… (Guangming Daily, http://bitly.ws/A57G, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

3.2.3. Patterns of propriety

- (1)

- Ms. Cai, a nurse from the Hankou Hospital, who just recovers from the COVID, is now donating plasma. She will be back to work at hospital on 22, February. … Ms. Guo works 10 h per day voluntarily and it’s often the case to work around the hour… Ms. Song sleeps less than 4 h per day. She works in “perpetual motion” including venipuncture, intubation, sampling, feeding patients and having chitchat with old patients. (China National Radio News, http://bitly.ws/A6aY, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (2)

- Mrs. Zhang has been pregnant for 5 weeks. The director finds her continuing the night shifts. (China Youth Net, http://bitly.ws/A6cc, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (1)

- Mr. Shen, a doctor from urinary surgery to rescue the fever clinic, says his wife warns him to wash hands regularly and his son wants to be a “Dragon Force warrior” to fight with him. (Guangming Daily, http://bitly.ws/A6cJ, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (3)

- She was the first one to apply for the fight after the notice of volunteer recruitment. At that time, her youngest son was only 10 months old. (xinhuanet, http://bitly.ws/A6dr, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (4)

- Even if her daughter was at a crucial period for the entrance examination, she left her to the elderly and took one for the team. (Economic Daily, http://bitly.ws/A6ds, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (5)

- Mrs. Zhou, a medical member from Anhui Province working at the makeshift hospital of Wuhan Sports Centre, left a message for her son on the protective suit “Chen** from the Hefei No.45 High School, please study hard!” (China Internet Information Center, http://bitly.ws/A6dt, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

3.3. Patterns of appreciation

- (1)

- Ms. Luo cried for those sisters who are in an age where great efforts are made to achieve beauty, but they have to cut their long hairs for the sake of efficiency in the wards. (Xinhua News Agency, http://bitly.ws/A6kx, (accessed on 28 November 2022))

- (2)

- For the sake of work and safety, Ms. Wang cut her beloved hair. Upon seeing her picture, her mom cried, “she never wore short hair before. Her smooth and attractive hair is her ‘lifeblood’. I’m so moved by her courage.” (The Paper, http://bitly.ws/A6kz, (accessed on 28 November 2022))

- (3)

- The ‘bald angel’ cut ‘Qing Si’. (Xinhua News Agency, http://bitly.ws/A6kB, (accessed on 28 November 2022))

3.4. Patterns of affect

- (1)

- Ms. Huang sobbed for the enthusiasm and warmth from Wuhan citizens. She said she has never been so moved. When she saw the bus driver, who was of the same age as her father and was in charge of the shuttle between the hotel and makeshift hospital, eat snacks right beside the flowerbed outside the hotel, she was bitter beyond expression. (Xinhua News Agency, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-03/27/c_1125776495.htm, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (2)

- Ms. Zheng, a shop volunteer, could not stop crying when receiving dozens of solicitudes from relatives and friends. (The Paper, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_6690889, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (3)

- A patient Ms. Fu was moved to tears when medical staff celebrated her birthday. (Economic Daily, https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1662048282545234649&wfr=spider&for=pc, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

- (4)

- Mr. Gong remembered that after finishing 5 surgeries for critically ill patients, he heard that there were 8 more to come. He immediately felt worried and stressed for the imminent fight. (China National Radio News, http://dl.cnr.cn/dlrw/20200329/t20200329_525034171.shtml, (accessed on 28 November 2022)).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-women (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Lariau, A.; Liu, L.Q. Inequality in the Spanish Labor Market during the COVID-19 Crisis. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2022/018/001.2022.issue-018-en.xml (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Del Boca, D.; Oggero, N.; Profeta, P.; Rossi, M. Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2020, 18, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, T.; Doepke, M.; Olmstead-Rumsey, J.; Tertilt, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26947/w26947.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Feng, Z.; Savani, K. COVID-19 created a gender gap in perceived work productivity and job satisfaction: Implications for dual-career parents working from home. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristal, T.; Yaish, M. Does the coronavirus pandemic level the gender inequality curve? (It doesn’t). Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 2020, 68, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, L.L. Women, Gender equality and COVID-19. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costoya, V.; Echeverría, L.; Edo, M.; Rocha, A.; Thailinger, A. Gender Gaps within Couples: Evidence of Time Re-allocations during COVID-19 in Argentina. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 43, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hipp, L.; Bünning, M. Parenthood as a driver of increased gender inequality during COVID-19? Exploratory evidence from Germany. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, S658–S673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, L.; Fawaz, Y.; González, L.; Graves, J. Gender Inequality in Paid and Unpaid Work During COVID-19 Times. Rev. Income Wealth 2022, 68, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, V. COVID: Not a Great Equalizer. Cesifo Econ. Stud. 2022, 66, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, J. Domestic help and the gender division of domestic labor during the COVID-19 pandemic: Gender inequality among Japanese parents. Jpn. J. Sociol. 2022, 31, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, O. Gendered Perspectives on COVID-19 Recovery in Africa: Towards Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-88151-1. [Google Scholar]

- Magar, V.; Gerecke, M.; Dhillon, I.S.; Campbell, J. Women’s contributions to sustainable development through work in health: Using a gender lens to advance a transformative 2030 agenda. In Health Employment and Economic Growth: An Evidence Base; Buchan, J., Dhillon, I.S., Campbell, J., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 27–50. ISBN 978-92-4-151240-4. [Google Scholar]

- Boniol, M.; McIsaac, M.; Xu, L.; Wuliji, T.; Diallo, K.; Campbell, J. Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries. Available online: http://bitly.ws/A3we (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- The World Bank Group Policy Note. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: http://bitly.ws/A3w5 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Press and Publicity Department of China. Transcript of News Press Conference on 8th March 2020. Available online: http://bitly.ws/A3vF (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Ao, R. Nurses Accounted for 70% in the Medical Teams Rescuing Hubei. Available online: http://bitly.ws/A3vy (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Martin, J.R.; White, P.R. The Language of Evaluation, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780230511910. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, G.; Alba-Juez, L. Evaluation in Context, 1st ed.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 9789027256478. [Google Scholar]

- A Specialized Website for New Coronavirus Pneumonia Prevention by Wuhan University. Available online: https://www.whu.edu.cn/xxfy/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Martin, J.R. Beyond exchange: Appraisal systems in English. In Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse; Hunston, S., Thompson, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 142–175. ISBN 0198299869. [Google Scholar]

- Zappavigna, M. Ambient affiliation: A linguistic perspective on Twitter. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 788–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.R.; Rose, D. Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause, 2nd ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 0-8264-8849-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R. The effability of semantic relations: Describing attitude. J. Foreign Lang. 2020, 43, 2–20. Available online: http://bitly.ws/A3ux (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Steuber, J. China: 3000 Years of Art and Literature, 1st ed.; Welcome Books: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-1599620305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Xie, K. Gendering National Sacrifices: The Making of New Heroines in China’s Counter-COVID-19 TV Series. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2022, 15, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansdell, P.; Thomas, K.; Hicks, K.M.; Hunter, S.K.; Howatson, G.; Goodall, S. Physiological sex differences affect the integrative response to exercise: Acute and chronic implications. Exp. Physiol. 2020, 105, 2007–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.F.; Cain, S.W.; Chang, A.-M.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Münch, M.Y.; Gronfier, C.; Wyatt, J.K.; Dijk, D.-J.; Wright, K.P.; Czeisler, C.A. Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108 (Suppl. S3), 15602–15608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.J.; Kurzer, M.S.; Calloway, D.H. Menstrual cycle and basal metabolic rate in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 36, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Aungsuroch, Y. Work stress, perceived social support, self-efficacy and burnout among Chinese registered nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, J.; Ma, X.; et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhang, L.; Lang, Q.; Liao, C.; Wang, N.; Qin, M.; Huang, H. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Lei, W.; Liu, H.; Hang, R.; Tao, X.; Zhan, Y. Nurses’ sleep quality of “Fangcang” hospital in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossari, M.; Chaudhry, S. Women and burnout in the context of a pandemic. Gend. Work. Organ. 2020, 28, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2002; pp. 189–194. ISBN 0-203-90009-X. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux, K.; Lewis, L.L. Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Lansdall-Welfare, T.; Sudhahar, S.; Carter, C.; Cristianini, N. Women Are Seen More than Heard in Online Newspapers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, A.H. Sex differences in emotionality: Fact or stereotype? Fem. Psychol. 1993, 3, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, H.J. Beliefs About Emotion Are Tied to Beliefs About Gender: The Case of Men’s Crying in Competitive Sports. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, L.R.; Shields, S.A. The perception of crying in women and men: Angry tears, sad tears, and the “right way” to cry. In Group Dynamics and Emotional Expression; Hess, U., Philippot, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2007; pp. 92–117. ISBN 978-0521842822. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen, G.V.; Richeson, J.A. Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. In Advanced Social Psychology: The State of the Science; Baumeister, R.F., Finkel, E.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 341–383. ISBN 978-0195381207. [Google Scholar]

- Elorza, I. Ideational Construal of Male Challenging Gender Identities in Children’s Picture Books. In A Multimodal Approach to Challenging Gender Stereotypes in Children’s Picture Books; Moya-Guijarro, A.J., Ventola, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 42–68. ISBN 978-0-367-70359-2. [Google Scholar]

- Huan, C. The strategic ritual of emotionality in Chinese and Australian hard news: A corpus-based study. Crit. Discourse Stud. 2017, 14, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia–National Report: Who Makes the News? Available online: https://whomakesthenews.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Australia.2020-GMMP-Country-Report-Australia.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Ross, K. The journalist, the housewife, the citizen and the press: Women and men as sources in local news narratives. Journalism 2007, 8, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, N. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory, 1st ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2003; ISBN 0-7486-1597-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hentschel, T.; Heilman, M.E.; Peus, C.V. The Multiple Dimensions of Gender Stereotypes: A Current Look at Men’s and Women’s Characterizations of Others and Themselves. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippa, R.A.; Preston, K.; Penner, J. Women’s Representation in 60 Occupations from 1972 to 2010: More Women in High-Status Jobs, Few Women in Things-Oriented Jobs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Botts, T.F. Feminist Thought: A More Comprehensive Introduction, 1st ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; ISBN 9780813349954. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, A. Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, 1st ed.; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 0-393-31284-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fuoli, M.; Hommerberg, C. Optimising transparency, reliability and replicability: Annotation principles and inter-coder agreement in the quantification of evaluative expressions. Corpora 2015, 10, 315–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Media Name | Introduction | Number |

| People’s Daily (People’s Daily Online/ People’s Forum/ cpcnews.cn) | The largest newspaper group in China that provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of China. http://www.people.com.cn/, http://www.rmlt.com.cn/, http://cpc.people.com.cn | 26 |

| Xinhua News Agency (Xinhuanet/ Xinhua Daily Telegraph/ xhby.net) | The official state news agency of China, and the largest news- and information-gathering and release center in China. http://xinhuanet.com/, https://www.xhby.net | 21 |

| Guangming Daily (Guangming Online) | Popular among Chinese intellectual circles, and focuses on the fields of education, science and technology, and culture and theory. https://www.gmw.cn | 18 |

| The Paper | A Chinese digital newspaper owned and run by the Shanghai United Media Group. https://www.thepaper.cn | 16 |

| China Internet Information Center | A key state news website for China in international communication. It provides round-the-clock news services in 10 languages. http://www.china.com.cn | 12 |

| CCTV News (cctv.com) | A news channel of China Central Television. https://news.cctv.com | 10 |

| Health News | An authoritative national newspaper on the healthcare industry run by the National Health Commission of China. https://www.jkb.com.cn | 6 |

| Worker’s Daily | The official newspaper of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions. https://www.workercn.cn | 6 |

| China National Radio News | A national radio network of China owned by the state-owned China Media Group. https://www.cnr.cn | 5 |

| China Youth Daily | An official newspaper of the Communist Youth League of China, whose target audience is young people. http://zqb.cyol.com | 4 |

| Economic Daily | A Chinese newspaper focusing on economic reports. http://paper.ce.cn/, http://www.ce.cn | 3 |

| Jiefang Daily | The official daily newspaper of the Shanghai Committee of the CCP. https://www.jfdaily.com | 2 |

| People’s Liberation Army Daily | A newspaper covering news stories relating to the PLA and other military affairs. http://www.81.cn | 2 |

| China News Service/ (China Newsweek) | The second largest state news agency in China, directed at overseas Chinese diaspora worldwide. (China Newsweek is a Chinese weekly magazine that covers domestic and international news, specializing in current affairs, culture, and politics.) https://www.chinanews.com/, http://www.inewsweek.cn | 2 |

| China Youth Net | The largest mainstream media platform for young people in China. https://www.youth.cn | 2 |

| Sichuan Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. https://www.scdaily.cn | 2 |

| Qiushi | A leading Chinese theoretical journal whose contributors include scholars and researchers of China’s think tanks and academic institutions. http://www.qstheory.cn | 2 |

| Science and Technology Daily | The official newspaper of the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, regarded as the authority for science and technology issues with objective and scientific perspectives. http://digitalpaper.stdaily.com | 2 |

| Hebei Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province. https://hbrb.hebnews.cn | 2 |

| ScienceNet | Supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Engineering, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, with the mission of establishing a global Chinese science community. http://www.sciencenet.cn | 1 |

| Guangxi Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Guangxi Province. https://gxrb.gxrb.com.cn | 1 |

| Shaanxi Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Shaanxi Province. https://esb.sxdaily.com.cn | 1 |

| Chongqing Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Chongqing Province. https://www.cqrb.cn | 1 |

| China Education News | A national newspaper focusing on the field of education in China. http://paper.jyb.cn/ | 1 |

| Beijing Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Beijing Province. https://www.bjd.com.cn | 1 |

| Hubei Daily | A leading Chinese language daily newspaper based in Hubei Province. https://epaper.hubeidaily.net | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, S.; Zou, L. Narratives of Women and Gender Relations in Chinese COVID-19 Frontline Reports in 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054359

Fang S, Zou L. Narratives of Women and Gender Relations in Chinese COVID-19 Frontline Reports in 2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054359

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Shuoyu, and Li Zou. 2023. "Narratives of Women and Gender Relations in Chinese COVID-19 Frontline Reports in 2020" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054359

APA StyleFang, S., & Zou, L. (2023). Narratives of Women and Gender Relations in Chinese COVID-19 Frontline Reports in 2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054359